BioImpacts. 6(4):183-185.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2016.24

Editorial

Nanoparticle patterning for biomedicine

Seyed Moein Moghimi *

Author information:

School of Medicine, Pharmacy and Health, Durham University, Queen’s Campus, Stockton-on-Tees TS17 6BH, UK

Abstract

Summary

Nanoparticles are being used for construction of complex and higher-order functional structures and metamaterials with applications in nanophotonics, information storage and biomedicine, to name a few. These innovations are briefly discussed within the context of future diagnostic and nanomedicine platform technologies and their possible self-assembly in vivo.

Keywords: Binary nanoparticle patterns, Microspheres, Nanospheres, Self-assembly

Copyright and License Information

© 2016 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Nano and microparticles have long been used in experimental and clinical medicine and particularly for therapeutic, diagnostic and theranostic purposes.

1

For instance, the diagnostic applications of polymeric particles goes back to mid-1950s with the invention of latex particle immunoagglutination tests, based on surface modification of polystyrene particles with antibodies.

2

Today, the availability of different particle types together with advances in sophisticated surface engineering methodologies and characterization procedures is increasing multifunctionality of the particulate systems.

1

As such, these innovations are also being applied as functional tools for fundamental understanding of dynamic and multifaceted cellular events and molecular processes that contribute to pathogenesis of many diseases.

In line with the above developments, significant advances are being made in assembling and positioning of nanoparticles for construction of complex and higher-order functional structures on different substrates. Controlled positioning of nanoparticles may be achieved either in pre-defined templates fabricated by top–down approaches or through self-assembly and/or backfilling.

3-9

For instance, a recent study reported on the spontaneous formation of ordered gold and silver nanoparticle stripe patterns on de-wetting a dilute film of polymer-coated nanoparticles floating on a water surface.

4

Transferring nanoparticles from the floating film onto an appropriate substrate resulted in the formation of aligned stripe patterns with tunable orientation, thickness and periodicity at the micrometer scale.

4

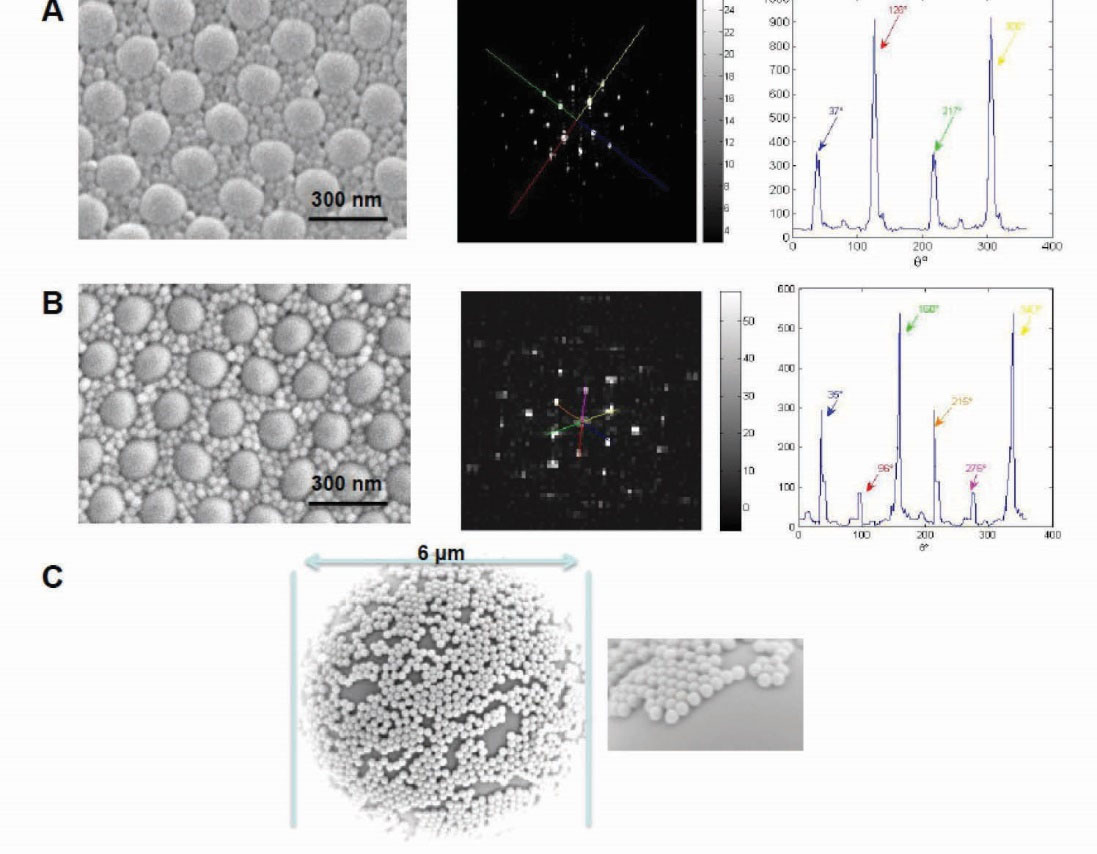

Our own approach have focused in spontaneous formation of ordered patterns from binary mixtures of polymeric nanoparticles of different sizes and surface chemistry resulting in either hexagonal or cubical arrangements with multiple periodicities and regular spacing over micrometer scales on a hydrophobic surface (Fig. 1A&B).

3

These patterned structures have remained stable under a number of different media. The mechanisms are poorly understood, but presumably entropy driven, optimizing space, however, a capillary flow phenomenon together with water evaporation may be a key contributing factor. Depending on the nanostructure properties and make up, water evaporation may even generate electricity.

10

Nevertheless, these developments could allow for further manipulation of surface structure and chemistry, thereby opening the path for design and engineering of sensor implants and stimuli-sensitive architectures for combination drug release with variable rates. Other applications may include studying interfacial phenomena (e.g., differential protein adsorption and complement activation turnover), design of high-performance and ultra-sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and tissue engineering, such as promoting regulated cell adhesion patterning (e.g., through topographic and chemical structuring).

11,12

Fig. 1.

Scanning electron micrographs and fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis of platform arrays assembled from polymeric nano and microspheres. (A) Two component lattice from mixtures of sulfated polystyrene nanoparticles of 350 nm and 60 nm showing square arrangement for larger nanoparticles (left); reciprocal lattice, FFT (middle); overlap integral showing ~90° between the peaks (right). (B) Two component lattice from mixtures of sulfated polystyrene nanoparticles of 350 nm and 60 nm showing hexagonal arrangement of larger nanoparticles (left); reciprocal lattice, FFT (middle); overlap integral showing ~60° between the peaks (right). (C) Self-assembly of surface functionalized polystyrene nanospheres of 350 nm on a 6 µm microsphere (left); a magnified view of microsphere curvature with deposited nanospheres in a hexagonal arrangement (right). Modified with permission.

3,13

.

Scanning electron micrographs and fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis of platform arrays assembled from polymeric nano and microspheres. (A) Two component lattice from mixtures of sulfated polystyrene nanoparticles of 350 nm and 60 nm showing square arrangement for larger nanoparticles (left); reciprocal lattice, FFT (middle); overlap integral showing ~90° between the peaks (right). (B) Two component lattice from mixtures of sulfated polystyrene nanoparticles of 350 nm and 60 nm showing hexagonal arrangement of larger nanoparticles (left); reciprocal lattice, FFT (middle); overlap integral showing ~60° between the peaks (right). (C) Self-assembly of surface functionalized polystyrene nanospheres of 350 nm on a 6 µm microsphere (left); a magnified view of microsphere curvature with deposited nanospheres in a hexagonal arrangement (right). Modified with permission.

3,13

In a separate attempt, nanospheres were spontaneously deposited in a patterned manner on the surface of a microsphere (Fig. 1C).

13

Such systems have the potential to act as multi-antigen depot platform adjuvants. For instance, different nanospheres may carry different antigens, where both nanosphere and antigen release rates may be controlled by microenvironmental stimuli and/or external signals. Here, systems multifunctionality may further modulate dendritic cell responses.

Finally, approaches and strategies that will allow formation of desirable patterns from combinations of inorganic, organic and composite nanoparticles of different size, shape and surface characteristics and excellent scalability will surely enhance innovations in metamaterial development, nanophotonics, information storage and biomedicine. With respect to biomedicine, a grand challenge, however, is how to promote spontaneous pattern formation of desirable properties, periodicity and dimensions on biological surfaces in vivo (e.g., within interstitial spaces, peritoneal cavity or the oral cavity) on nanoparticle administration for therapeutic, diagnostic and sensing applications. We know from in vitro experiments that surfactant-coated polystyrene nanoparticles, and depending on the surfactant concentration, can form highly ordered geometrical platforms.

14

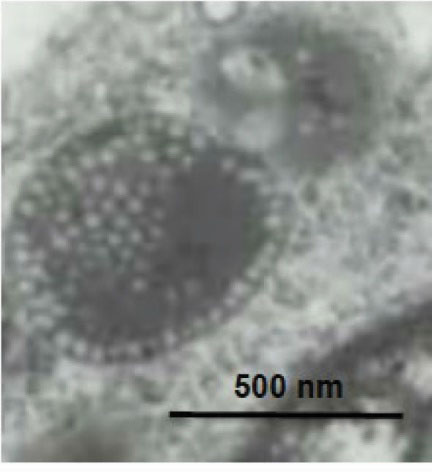

In the intestine, orally delivered nanoparticles are exposed to bile surfactants. Therefore, possible interaction of these natural surfactants with nanoparticles may incite local patterning, thereby modulating nanoparticle motion, bacterial adhesion, processing and functionality. Some evidence, however, suggests that nanoparticle patterning could occur intracellularly, such as in lysosomal compartments (Fig. 2), but the mechanisms and the driving forces remain unknown. However, the mode and the extent of nanosphere ingestion, as well as lysosome size and volume, may play a significant role in lysosomal packaging order and most likely with stochastic outcome. Depending on nanoparticle type, shape and composition, such intracellular compartmental patterning may play an important role in nanoparticle stability, the rate of degradation and the extent of drug release. An intriguing possibility would be if different pattern formation could modulate lysosomal functionality differently. These issues deserve detailed investigation.

Fig. 2.

An electron micrograph of a rat interstitial macrophage lysosome. The lysosome contains some ordered arrangement of randomly ingested polystyrene nanospheres (60 nm) by the macrophage. Nanospheres were injected subcutaneously into the rat footpad. Nanospheres are positioned in a monolayer format close to the edge of the inner portion of the lysosome membrane. In the upper left section, a second layer of nanospheres is emanating; this spiral into a cluster where hexagonal-pentagonal packing arrangements are visible.

.

An electron micrograph of a rat interstitial macrophage lysosome. The lysosome contains some ordered arrangement of randomly ingested polystyrene nanospheres (60 nm) by the macrophage. Nanospheres were injected subcutaneously into the rat footpad. Nanospheres are positioned in a monolayer format close to the edge of the inner portion of the lysosome membrane. In the upper left section, a second layer of nanospheres is emanating; this spiral into a cluster where hexagonal-pentagonal packing arrangements are visible.

Ethical approval

There is none to be declared.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Andresen TL. Factors controlling nanoparticle pharmacokinetics: an integrated analysis and perspective. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2012; 52:481-503. [ Google Scholar]

- Singer Singer, JM JM, Plotz Plotz, CM CM, The latex fixation test. II Clinical results in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 1956; 21:888-92. [ Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay R, Al-Hanbali O, Pillai S, Hemmersam AG, Meyer ML, Hunter AC, Rutt KJ, Besenbacher F, Moghimi SM, Kingshott P. Ordering of binary polymeric nanoparticles on hydrophobic surfaces assembled from low volume fraction dispersions. J Am Chem Soc 2007; 129:13390-1. [ Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Kim Kim, F F, Tao AR, Connor S, Yang P. Spontaneous formation of nanoparticle stripe patterns through dewetting. Nat Mat 2005; 4:896-900. [ Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Lee I, Rubner MF, Hammond PT. Two component particle arrays on patterned polyelectrolyte multilayer templates. Adv Mat 2002; 14:569-72. [ Google Scholar]

- Hua F, Shi J, Cui T. Patterning of layer-by-layer self-assembled multiple types of nanoparticle thin films by lithographic technique. Nano Lett 2002; 2:1219-22. [ Google Scholar]

- Kim MH, Im SH, Park OO. Fabrication and structural analysis of binary colloidal crystals with two-dimensional superlattices. Adv Mat 2005; 17:2501-5. [ Google Scholar]

- Kiely CJ, Fink J, Brust M, Bethell D, Schiffrin DJ. Spontaneous ordering of bimodal ensembles of nanoscopic gold clusters. Nature 1998; 396:444-6. [ Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Slotcavage D, Mai JD, Liang W, Xie Y, Chen Y, Huang TJ. Combining the masking and scaffolding modalities of colloidal crystal templates: plasmonic nanoparticle arrays with multiple periodicities. Chem Mater 2014; 25:6432-8. [ Google Scholar]

-

Xue G, Xu Y, Ding T, Li J, Fei W, Cao Y, et alW. Water-evaporation-induced electricity with nanostructured carbon materials. Nat Nanothecnol 2017.

-

Chen F, Wang G, Griffin JI, Brenneman B, Banda NK, Holers VM, et al. Complement proteins bind to nanoparticle protein corona and undergo dynamic exchange in vivo. Nat Nanotechnol 2017.

-

Emmerich F, Thielemann C. Patterns of charged gold nanoparticles for cell adhesion control. Front Neurosci Conference Abstract: MEA Meeting (10th International Meeting on Substrate-Integrated Electrode Arrays) 2016. doi: 10.3389/conf.fnins.2016.93.00087.

- Moghimi SM. Nanoparticle engineering for the lymphatic system and lymph node targeting In: Broz P, ed Polymer-Based Nanostructures: Medical Applications RCS Publishing, Cambridge. RCS Nanosci Nanotechnol 2010; 9:81-97. [ Google Scholar]

- Hunter AC, Elsom J, Wibroe PP, Moghimi SM. Polymeric particulate technologies for oral drug delivery and targeting: a pathophysiological perspective. Nanomedicine 2012; 8:S5-20. [ Google Scholar]