BioImpacts. 7(4):241-246.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2017.28

Original Research

Spectroscopic, thermodynamic and molecular docking studies of bovine serum albumin interaction with ascorbyl palmitate food additive

Yousef Sohrabi 1, 2, Vahid Panahi-Azar 3, Abolfazl Barzegar 4, Jafar Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi 5, *  , Parvin Dehghan 1, *

, Parvin Dehghan 1, *

Author information:

1Nutrition Research Center, Department of Food Science and Technology, School of Nutrition, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2Student Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3Drug Applied Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4Research Institute for Fundamental Sciences, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

5Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

Ascorbyl palmitate (AP) is an example of natural secondary food antioxidant, which has been used for oxidative rancidity prevention in food industry. In this study, the interaction of AP with bovine serum albumin (BSA) was investigated.

Methods:

The mechanism of BSA interaction with AP was investigated using spectroscopic methods (UV-Vis, fluorescence). The thermodynamic parameters including enthalpy change (ΔH), entropy change (ΔS), and Gibb’s free energy (ΔG) were calculated using Van’t Hoff equation at different temperatures.

Results:

The experimental results showed that UV-Vis absorption spectra of BSA decreased upon increasing AP concentration, indicating that the AP can bind to BSA. Formation of the AP-BSA complex was approved by quenching of fluorescence and the quenching mechanism was found to be resultant from dynamic procedure. The positive values of both ΔH and ΔS showed that hydrophobic forces were the major binding forces. The negative value of ΔG demonstrated that AP interacts with BSA spontaneously. Molecular docking results confirmed that AP binds to BSA through hydrophobic forces.

Conclusion:

The attained results showed that AP can bind to BSA and effectively distributed into the bloodstream.

Keywords: Ascorbyl palmitate, Bovine serum albumin, Food additive, Thermodynamic parameters

Copyright and License Information

© 2017 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Food additives are widely used in food industry for a technological purpose in the manufacture, preparation, processing, packaging treatment, storage, and increasing shelf life or enhancing nutritive value of the food in recent decades. Food antioxidants are examples of common food additives, which are effective in preserving unsaturated oils, many edible animal fats, meat products and cosmetic products from fat rancidity, spoilage and color changes.

1

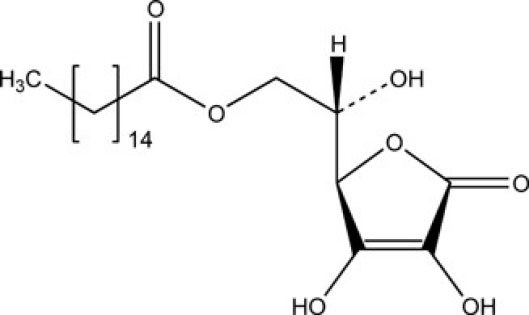

Ascorbyl palmitate (AP) is an amphipathic ester of vitamin C (Fig. 1), which has been proposed as a safe natural secondary food antioxidant by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in food industry, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and medical.

2,3

Application of AP lead to oxidative rancidity prevention by quenching singlet oxygen, thus turning into an oxidize, which has no antioxidant activity. Currently, AP has been applied as a synergistic antioxidant together with other antioxidant additives such as tert-Butylhydroquinone, butylated hydroxyanisole and butylated hydroxytoluene in food industries. However, some side effects as well as hyperplasia in rats fed with high levels of AP, decrease in body weight gain, and oxalate stones formation in the bladder was reported by various researchers.

4

Due to widespread use of AP in food industry, human exposure is high to this additive. Therefore, investigation of conformational changes in biological macromolecules such as albumin and DNA upon interaction with AP can be important.

5

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of ascorbyl palmitate.

.

Chemical structure of ascorbyl palmitate.

Serum albumin is main soluble protein with a high concentration in blood circulation system and important biological roles. The transportation and availability of various molecules and materials in the blood circulatory system has been regulated by albumin. Serum albumins not only regulate hydrophobic compounds delivery to cells but also enhance their solubility in plasma.

6,7

Therefore, the adsorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, stability and toxicity of the blood-borne chemical substances have been affected due to albumin interaction with chemical compounds and molecules. Furthermore, it was reported that albumin interaction with chemical compounds may affect the secondary and tertiary structure of it. Finally, investigation on chemical compounds interaction with albumin may provide essential information on metabolism, transport and excretion process of chemical compounds, which will help in interpretation of the relationship between structure and function.

6,8

The interaction of AP with bovine serum albumin (BSA) using spectrophotometry and molecular docking has not been reported. Owing to the extensive use of AP in food and pharmaceutical industries, investigation of its binding to BSA should be carried out. Therefore, in this article, the binding properties of AP with BSA have been investigated using spectroscopic methods.

Materials and methods

Materials

BSA (Fatty acid free ˂0.05 %), Tris-HCl buffer and AP were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co., (Poole, UK).

Preparation of stock solutions

To prepare BSA stock solution, an appropriate amount of BSA was dissolved in aqueous solution containing Tris buffer (10mM, pH 7.4). Determination of protein concentration was done by UV–Vis spectrophotometry through the molar absorption coefficient (ε =35700 M-1 cm-1) at 287 nm.

The preparation of AP stock solution was done by dissolving proper amount of AP in ethanol and double distilled water (at ratio of 5/95).

UV–Vis spectrophotometry

UV–Vis spectroscopic study was performed using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer, T 60, PG Instrument (Leicestershire, UK). UV–Vis spectrophotometry experiment was performed by varying the AP concentration from 0 to 5 × 10-5M and holding the concentration of BSA at 1 × 10-6 M.

Fluorescence spectra measurements

All fluorescence spectra were performed with a spectrofluorimeter, Jasco FP-750 equipped with a 150 W Xenon lamp and thermostatic cuvette holder (Kyoto, Japan). The maximal fluorescence emission of BSA at λex = 290 nm was located at 350 nm. The fluorescence intensity of BSA was carried out at the constant concentration of BSA (1.0 × 10-6 M) while changing the AP concentration (0 to 5.0 × 10-5 M).

The Stern–Volmere equation was applied for analysis of fluorescence quenching results Eq. (1):

where, F0 is BSA fluorescence intensity in the absence of AP

(quencher) and F is at the existence of AP, respectively. KSV is constant of Stern–Volmer quenching and is demonstrative of fluorescence quenching efficiency due to addition of AP and [Q] is the concentration of the AP.

6

Therefore, Eq. (1) was applied to determine KSV by a linear regression of F0/F versus [Q].

The binding constant (Kb) and the binding stoichiometry (n) was calculated through the equation 2 (Eq. 2)

6

:

(Eq. 2)

where, n is demonstrative of binding sites number per albumin molecule and Kb is indicative of binding constant for the interaction of AP with BSA, which can be calculated through the intercept and the slope of the double logarithm regression curve of log((F0−F)/F) versus log [AP] based on the Eq. 2.

Thermodynamic analyses

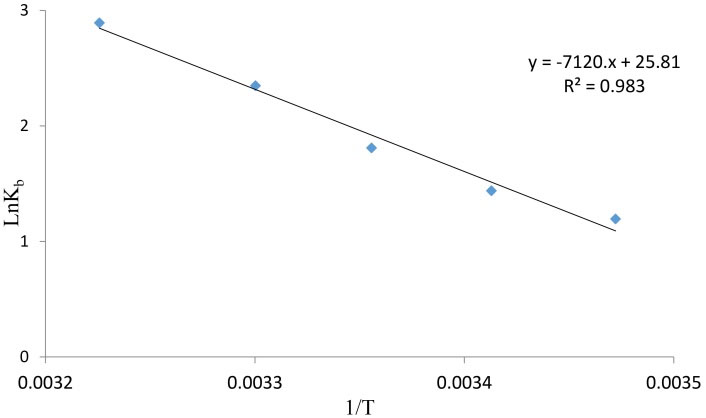

The effect of temperature on AP binding was evaluated to derive the thermodynamic functions of AP–BSA complex formation. Fluorescence spectra were measured at five different temperatures (288, 293, 298, 303 and 310 °K). The thermodynamic parameters of AP interaction with BSA was attained via Van't Hoff equation by plotting of lnKb against 1/T allows (Eq. 3)

6,9

:

Changes in Gibs free energy (∆G) were calculated through the following standard equation (Eq. 4)

6,10

:

Molecular docking study

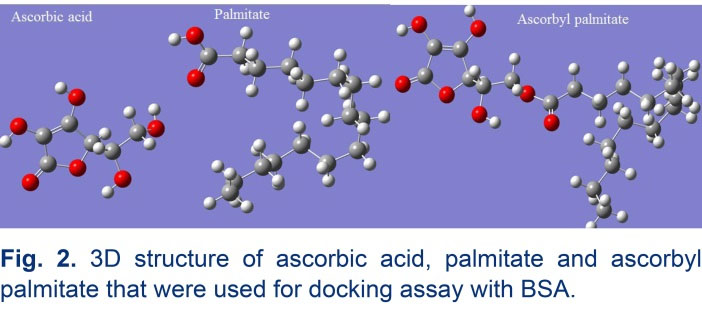

AutoDock was applied as a beneficial tool to search the whole surface of BSA protein for the possible location of the ligand binding sites. Crystal structures of palmitic acid, ascorbic acid and BSA were achieved from pdb entries 5B28, 4JTP, and 4OR0, respectively. 3D geometry of ascorbyl palmitate was generated from palmitic acid (5B28) and ascorbic acid (4JTP) by GaussView 5.0.8. The 3D geometry of ascorbic acid, palmitate and AP was presented in Fig. 2. Therefore, we have applied 500 docking runs against BSA to search the whole surface of the protein using palmitic acid (100 runs), ascorbic acid (100 runs), AP (300 runs). The lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA), was used to accomplish an automated molecular docking. Except for the energy assessments and docking runs that were set to 2 500 000 and 100, respectively, default parameters were applied. A number of grid points in xyz were 126*126*126 separated by 0.725 Å at the middle of the protein. All of the docking evaluations were carried out with the program AUTODOCK 4.2 Release 4.2.6.

6,11

Fig. 2.

3D structure of ascorbic acid, palmitate and ascorbyl palmitate that were used for docking assay with BSA.

.

3D structure of ascorbic acid, palmitate and ascorbyl palmitate that were used for docking assay with BSA.

Results

Effect of the AP on UV spectra of BSA

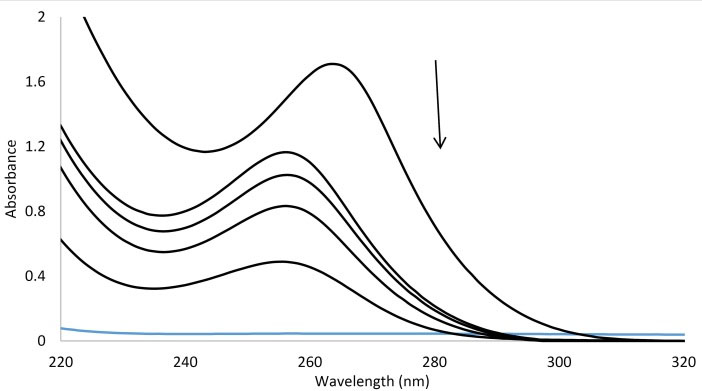

Fig. 3 shows the absorption spectra of BSA while increasing amount of the AP in an aqueous Tris buffer of pH 7.4. Addition of AP resulted in the decrease of BSA absorbance, which confirmed protein conformation alteration upon binding to AP.

Fig. 3.

Uv/Vis spectra of BSA in the absence and the presence of the increasing AP, [BSA] = 1 × 10-6 M and [AP] = 0, 1, 5, 10, 50 ×10-6 M.

.

Uv/Vis spectra of BSA in the absence and the presence of the increasing AP, [BSA] = 1 × 10-6 M and [AP] = 0, 1, 5, 10, 50 ×10-6 M.

Fluorescence studies

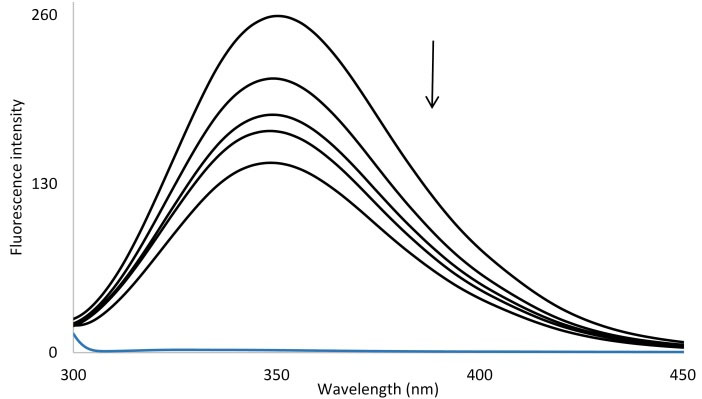

As it is shown in Fig. 4, AP concentration increase resulted in the decrease of BSA fluorescence spectra on a regular basis and verified AP interaction with BSA and hence quenching of its intrinsic fluorescence. The calculated KSV values were presented in Table 1.

Fig. 4.

Fluorescence spectra of BSA in the absence and the presence of the increasing AP in double distilled water (pH = 7.4) at room temperature, [BSA] = 1 × 10-6 M and [AP] = 0, 1, 5, 10, 50 ×10-6 M.

.

Fluorescence spectra of BSA in the absence and the presence of the increasing AP in double distilled water (pH = 7.4) at room temperature, [BSA] = 1 × 10-6 M and [AP] = 0, 1, 5, 10, 50 ×10-6 M.

Table 1.

Stern–Volmer quenching constants (KSV) of AP-BSA complex at different temperatures

|

T

(K)

|

K

sv

(M

-1

)

|

n

|

| 288 |

4.48 × 103

|

1.369 |

| 293 |

4.96 × 103

|

1.352 |

| 298 |

6.05 × 103

|

1.285 |

| 303 |

7.94 × 103

|

1.256 |

| 310 |

9.28 × 103

|

1.332 |

Binding constant and number of binding sites

When various compounds bind individually to a series of equal sites on albumin, the binding constant (Kb) and the binding stoichiometry (n) can be attained using the equation 2. The calculated Kb values were presented in Table 2, which indicates Kb increase with the rising temperature. The Kb value showed that interaction between BSA and AP has been occurred and value of n demonstrated that there is a set of binding sites available on BSA for AP.

9,10,12

Table 2.

Binding constants (Kb) and thermodynamic parameters for the binding of AP to BSA at various temperatures

|

T

(K)

|

K

b

|

lnK

b

|

ΔG

o

(kJ mol

-1

)

|

ΔH

o

(kJ mol

-1

)

|

ΔS

o

(J mol

-1

K

-1

)

|

| 288 |

3.304 |

1.195 |

-2.605 |

59.206 |

214.622 |

| 293 |

4.216 |

1.439 |

-3.678 |

59.206 |

214.622 |

| 298 |

6.109 |

1.809 |

-4.751 |

59.206 |

214.622 |

| 303 |

10.47 |

2.348 |

-5.824 |

59.206 |

214.622 |

| 310 |

18.03 |

2.892 |

-7.326 |

59.206 |

214.622 |

Thermodynamic parameters of BSA interaction with AP

Thermodynamic parameters for the interaction of AP with BSA were determined using the van’t Hoff equation (Eq. 3, Fig. 5). The values of ΔH, ΔS and ΔG upon binding of AP to BSA are listed in Table 2.

Fig. 5.

The van't Hoff plot for the interaction of BSA and AP, [BSA] = 1 × 10-6 M and [AP] = 0, 1, 5, 10, 50 ×10-6 M.

.

The van't Hoff plot for the interaction of BSA and AP, [BSA] = 1 × 10-6 M and [AP] = 0, 1, 5, 10, 50 ×10-6 M.

Molecular docking study

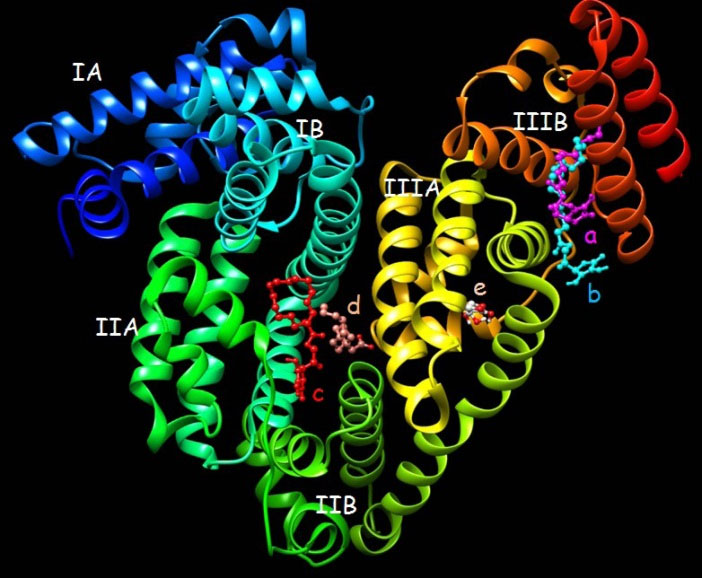

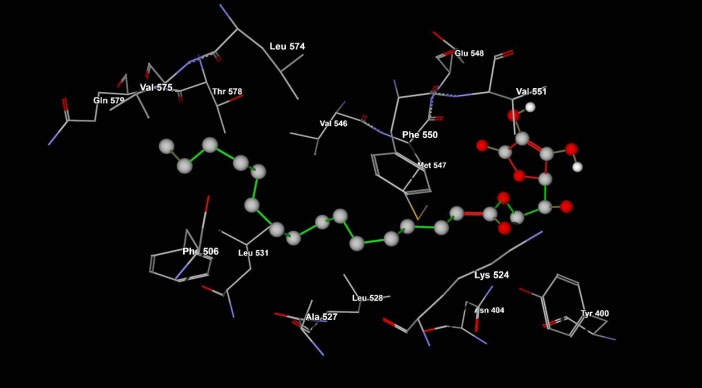

Different docking runs have been done including; palmitic acid (100 runs), ascorbic acid (100 runs). Since, AP has more torsion degree of freedom (TDF, Fig. 6) that possibly causes some unwanted errors in docking results, therefore three different docking states for this ligand were applied as the completely flexible state (100 runs, with 20 TDF), moderate flexible state (100 runs, with 12 TDF) and rigid state (100 runs, with 0 TDF). The docking energies for each compound were provided in Table 3. Data clearly indicate that the AP compound has affinity to interact with BSA. The affinity of AP to BSA is affected from two important parameters. First; the fragment part of palmitate enhances these interactions (with the lowest binding energy of -5.12 kcal/mol but the ascorbyl fragment decreases and prevents the BSA and ligand interactions (with the lowest binding energy of +0.55 kcal/mol). Because of the highly favorite interactions from palmitate fragment compared to unfavorite property of ascorbyl fragment, the AP interacted on the surface of BSA with the suitable energy (Table 3). Second; the moderate flexible state of AP results in improved interactions. Application of moderate flexible state has not resulted in changing of the binding site location on BSA as indicated in Fig. 6. Both of high and moderate flexible state of AP intended to interact with site IIIB of BSA. The important interacted residues with AP have been presented in Fig. 7. It indicates that hydrophobic residues on BSA site IIIB are interacted with AP. It is possibly because of highly hydrophobic property of AP. Compared to the ascorbyl, palmitate and AP data in Table 3, confirms the importance of hydrophobic effects for the affinity of AP to BSA hydrophobic residues.

Fig. 6.

The lowest docked conformations for ascorbyl palmitate, palmitate and ascorbic acid. a, b, c, d and e correspond to the lowest binding modes of completely flexible ascorbyl palmitate (20 TDF), moderate flexible ascorbyl palmitate (12 TDF), rigid ascorbyl palmitate (0 TDF), palmitate and ascorbic acid, respectively.

.

The lowest docked conformations for ascorbyl palmitate, palmitate and ascorbic acid. a, b, c, d and e correspond to the lowest binding modes of completely flexible ascorbyl palmitate (20 TDF), moderate flexible ascorbyl palmitate (12 TDF), rigid ascorbyl palmitate (0 TDF), palmitate and ascorbic acid, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Ascorbyl palmitate binding residues on BSA structure that were achieved from lowest binding energy run (Table 1). The residues related to ascorbyl palmitate/BSA complex between the length of 4 Å.

.

Ascorbyl palmitate binding residues on BSA structure that were achieved from lowest binding energy run (Table 1). The residues related to ascorbyl palmitate/BSA complex between the length of 4 Å.

Table 3.

Docking binding energy (kcal/mol) of ascorbyl palmitate EAP, palmitate EP, and ascorbic acid EA, with BSA (only first 30 ranking energy of 100 runs were provided)

|

Class

|

a

E

AP

|

b

E

AP

|

c

E

AP

|

E

P

|

E

A

|

| 1 |

-3.75 |

-5.51 |

-1.95 |

-5.12 |

0.55 |

| 2 |

-3.57 |

-4.27 |

-1.95 |

-4.89 |

0.75 |

| 3 |

-3.19 |

-3.93 |

-1.70 |

-4.59 |

0.79 |

| 4 |

-3.13 |

-3.43 |

-1.67 |

-4.46 |

0.89 |

| 5 |

-2.83 |

-3.36 |

-0.28 |

-4.18 |

0.98 |

| 6 |

-2.78 |

-3.24 |

-1.90 |

-4.13 |

0.99 |

| 7 |

-2.71 |

-3.15 |

-1.87 |

-4.08 |

1.08 |

| 8 |

-2.68 |

-3.1 |

-1.84 |

-4.06 |

1.19 |

| 9 |

-2.48 |

-3.04 |

-1.80 |

-4.02 |

1.25 |

| 10 |

-2.34 |

-3.00 |

-1.76 |

-4.01 |

1.25 |

| 11 |

-2.13 |

-2.99 |

-1.50 |

-3.98 |

1.26 |

| 12 |

-2.12 |

-2.98 |

-1.74 |

-3.39 |

1.27 |

| 13 |

-2.05 |

-2.97 |

-1.73 |

-3.28 |

1.28 |

| 14 |

-2.01 |

-2.92 |

-1.72 |

-3.27 |

1.35 |

| 15 |

-1.97 |

-2.83 |

-1.69 |

-3.08 |

1.37 |

| 16 |

-1.94 |

-2.8 |

-1.67 |

-3.05 |

1.37 |

| 17 |

-1.90 |

-2.76 |

-1.65 |

-2.99 |

1.38 |

| 18 |

-1.90 |

-2.73 |

-1.65 |

-2.99 |

1.39 |

| 19 |

-1.86 |

-2.72 |

-1.64 |

-2.90 |

1.39 |

| 20 |

-1.83 |

-2.71 |

-1.63 |

-2.88 |

1.44 |

| 21 |

-1.82 |

-2.71 |

-1.63 |

-2.73 |

1.47 |

| 22 |

-1.79 |

-2.66 |

-1.07 |

-2.68 |

1.48 |

| 23 |

-1.77 |

-2.59 |

-1.73 |

-2.66 |

1.50 |

| 24 |

-1.67 |

-2.48 |

-1.72 |

-2.65 |

1.51 |

| 25 |

-1.65 |

-2.45 |

-1.72 |

-2.64 |

1.57 |

| 26 |

-1.64 |

-2.38 |

-1.72 |

-2.61 |

1.58 |

| 27 |

-1.64 |

-2.37 |

-1.65 |

-2.58 |

1.59 |

| 28 |

-1.60 |

-2.36 |

-1.60 |

-2.56 |

1.60 |

| 29 |

-1.38 |

-2.31 |

-1.57 |

-2.53 |

1.60 |

| 30 |

-1.38 |

-2.09 |

-1.55 |

-2.48 |

1.61 |

a, b and c correspond to the docking binding energy of ascorbyl palmitate in different state including completely flexible state with 20 TDF, moderate flexible ligand with 12 TDF and rigid with 0 TDF, respectively.

Discussion

The protein conformational modification and formation of protein complex with numerous ligands can be investigated using spectroscopic technique. In this article, we evaluated absorption spectra change of BSA while varying the AP concentration. Upon addition of AP, the UV-Vis absorbance intensity of BSA was decreased, which shows complex formation between BSA and AP and protein conformation change.

Decrease process in the fluorescence intensity of a fluorophore is known as fluorescence quenching. Fluorescence quenching can occur by static quenching mechanisms or dynamic one. The formation of complex between quencher and the fluorophore results in static quenching, while dynamic quenching is because of the collision of the quencher and fluorophore during the excitation process. Static and dynamic quenching can be differentiated by the temperature dependency of the quenching process. Briefly, high temperature leads to large diffusion coefficient in the dynamic quenching. As a result, the bimolecular quenching constants are expected to increase with the temperature rising, but a reverse outcome would be attained for the static quenching. According to attained data rising temperature increased the KSV constants, which showed that the probable fluorescence-quenching of BSA upon addition of AP is dynamic mechanism.

13,14

The interaction of biomolecules such as albumin with various ligands may occur via hydrophobic forces, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, etc. Based on the data of ΔH and ΔS, the ligand and biomolecule interaction type can be estimated. The positive values of ΔH and ΔS is indicative of hydrophobic forces occurrence, the negative values of ΔH and ΔS shows happing of van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonds and finally, the negative value of ΔH and the positive value of ΔS is demonstrative of electrostatic interaction incidence. The positive values of both ΔH and ΔS indicated that the acting forces are mainly hydrophobic forces. Hydrophobic nature of BSA interaction with AP may be due to the presence of hydrophobic palmitate in AP structure. Besides, the negative values of ΔG revealed that the BSA and AP interaction process is spontaneous.

6,15

Finally, docking study was performed to identify; a) the probable AP binding sites on BSA structure, b) the role of “palmitic acid” and/or “ascorbic acid” fragments interactions with BSA structure, and c) the role of the flexibility of AP in binding affinity of ligand on BSA surface. Docking results showed that AP interact with BSA through hydrophobic residues on site IIIB.

Conclusion

In the current investigation, the BSA binding property of AP has been studied by UV–vis and fluorescence spectroscopies and molecular docking modeling. The attained results showed that AP binds to BSA through a dynamic quenching. The main interaction forces are hydrophobic forces and the interaction process is spontaneous and entropy driven. Molecular docking results confirmed that AP interacts with BSA through hydrophobic forced. It can be concluded that AP can bind to BSA and transfer into the bloodstream.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

None to be declared.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of this study by the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, which was a part of M.Sc thesis No: 117, Tabriz, Iran Tabriz, Iran.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

simple

-

√ AP interacts with BSA and the main acting force was

hydrophobic forces.

What is new here?

simple

-

AP binding to BSA was investigated using spectroscopic

and molecular docking methods.

References

- Hamishehkar H, Khani S, Kashanian S, Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Eskandani M. Geno- and cytotoxicity of propyl gallate food additive. Drug Chem Toxicol 2014; 37:241-6. doi: 10.3109/01480545.2013.838776 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Teneva O, Dimcheva N. Electrochemical assay of the antioxidant ascorbyl palmitate in mixed medium. Food Chem 2016; 203:35-40. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.02.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay R, Mishra HN. Predictive modeling for shelf life estimation of sunflower oil blended with oleoresin rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L) and ascorbyl palmitate at low and high temperatures. LWT - Food Sci Technol 2015; 60:42-9. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.09.029 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Martínez ML, Penci MC, Ixtaina V, Ribotta PD, Maestri D. Effect of natural and synthetic antioxidants on the oxidative stability of walnut oil under different storage conditions. LWT - Food Sci Technol 2013; 51:44-50. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.10.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Andersen FA. Final report on the safety assessment of ascorbyl palmitate, ascorbyl dipalmitate, ascorbyl stearate, erythorbic acid, and sodium erythorbate. Int J Toxicol 1999; 18:1-26. doi: 10.1177/109158189901800303 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Panahi-Azar V, Barzegar A, Jamali AA, Kheirdoosh F, Kashanian S. Spectroscopic and molecular modeling studies of human serum albumin interaction with propyl gallate. RSC Adv 2014; 4:64559-64. doi: 10.1039/C4RA11103F [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bolattin MB, Nandibewoor ST, Chimatadar SA. Biomolecular interaction study of hydralazine with bovine serum albumin and effect of β-cyclodextrin on binding by fluorescence, 3D, synchronous, CD, and Raman spectroscopic methods. J Mol Recognit 2016; 29:308-17. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2532 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Wu X. Review: Modifications of Human Serum Albumin and their Binding Effect. Curr Pharm Design 2015; 21:1862-5. [ Google Scholar]

- Shahabadi N, Maghsudi M, Rouhani S. Study on the interaction of food colourant quinoline yellow with bovine serum albumin by spectroscopic techniques. Food Chem 2012; 135:1836-41. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.095 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shahabadi N, Maghsudi M, Ahmadipour Z. Study on the interaction of silver(I) complex with bovine serum albumin by spectroscopic techniques. Spectrochim Acta A 2012; 92:184-8. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.02.071 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sharifi M, Dolatabadi JEN, Fathi F, Rashidi M, Jafari B, Tajalli H. Kinetic and thermodynamic study of bovine serum albumin interaction with rifampicin using surface plasmon resonance and molecular docking methods. J Biomed Opt 2017; 22:037002-

. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.22.3.037002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K, Rathi S, Arora D. Fluorescence spectral studies on interaction of fluorescent probes with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). J Lumin 2016; 175:135-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2016.01.029 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shahabadi N, Khorshidi A, Mohammadpour M. Investigation of the effects of Zn2+, Ca2+ and Na+ ions on the interaction between zonisamide and human serum albumin (HSA) by spectroscopic methods. Spectrochim Acta A 2014; 122:48-54. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2013.11.047 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shahabadi N, Hadidi S. Molecular modeling and spectroscopic studies on the interaction of the chiral drug venlafaxine hydrochloride with bovine serum albumin. Spectrochim Acta A 2014; 122:100-6. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2013.11.016 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shahabadi N, Fili SM. Molecular modeling and multispectroscopic studies of the interaction of mesalamine with bovine serum albumin. Spectrochim Acta A 2014; 118:422-9. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2013.08.110 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]