BioImpacts. 7(2):91-97.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2017.12

Original Research

Surface plasmon resonance and molecular docking studies of bovine serum albumin interaction with neomycin: kinetic and thermodynamic analysis

Maryam Sharifi 1, Jafar Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi 2, Farzaneh Fathi 2, 3, Mostafa Zakariazadeh 4, Abolfazl Barzegar 4, Mohammad Rashidi 2, Habib Tajalli 1, Mohammad-Reza Rashidi 2, *

Author information:

1Research Institute for Applied Physics and Astronomy, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

2Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3Student Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4Research Institute for Fundamental Sciences (RIFS), University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

The interactions between biomacromolecules such as serum albumin (SA) and various drugs have attracted increasing research attention in recent years. However, the study of SA with those drugs that have relatively high hydrophilicity and a lower affinity for SA could be a challenging issue. At the present study, the interaction of bovine SA (BSA) with neomycin as a hydrophilic drug has been investigated using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and molecular docking methods.

Methods:

BSA was immobilized on the carboxymethyl dextran hydrogel sensor chip after activation of carboxylic groups through NHS/EDC and, then, the neomycin interaction with BSA at different concentrations (1-128 µM) was investigated.

Results:

Dose-response sensorgrams of BSA upon increasing concentration of neomycin has been shown through SPR analysis. The small KD value (4.96 e-7 at 40°C) demonstrated high affinity of neomycin to BSA. Thermodynamic parameters were calculated through van’t Hoff equation at 4 different temperatures. The results showed that neomycin interacts with BSA via Van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonds and increase of KD with temperature rising indicated that the binding process was entropy driven. Molecular docking study confirmed that hydrogen bond was the major intermolecular force stabilizing neomycin-BSA complex.

Conclusion:

The attained results showed that neomycin molecules can efficiently distribute within the body after interaction with BSA in spite of having hydrophilic properties. Besides, SPR can be considered as a useful instrument for study of the interaction of hydrophilic drugs with SA.

Keywords: Enthalpy, Entropy, Equilibrium constants (KD), Surface plasmon resonance, Thermodynamic

Copyright and License Information

© 2017 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Antibiotics are one of the most widely used groups of drugs used in the treatment and prevention of bacterial infections. Neomycin is a highly water soluble (50 mg/mL) hydrophilic antibiotic with bactericidal properties against Gram negative bacteria and partially against Gram positive bacteria and usually used as an antimicrobial for the treatment of gastrointestinal infections and hepatic encephalopathy.

1

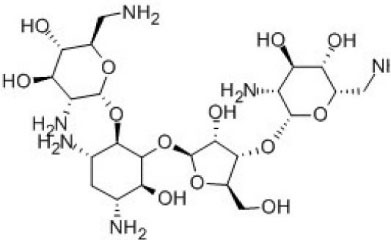

It belongs to aminoglycoside class of antibiotics with two or more aminosugars connected by glycosidic bonds and is available in various dosage forms such as creams, ointments and eye drops. Aminoglycosides cause misreading of t-RNA, leaving the bacterium unable to synthesize proteins vital to its growth through binding to the bacterial 30S ribosomal subunit (Fig. 1).

1,2

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of highly water soluble neomycin.

.

Chemical structure of highly water soluble neomycin.

Serum albumins (SAs) are the major soluble proteins in the circulatory system that acts as a depot and also a carrier for many endogenous and exogenous compounds such as drugs.

3-5

Bovine SA (BSA) is the most frequently used protein in the drug-protein interaction studies due to its structural homology with human SA (HSA), cheapness, easy availability and considerable stability.

6,7

It is a large monomeric protein (66 kDa) consisting of about 583 amino acid residues as single chain. The chain is made up of three homologous but structurally distinct domains (I-III); each consisting of 2 subdomains (A and B). Drug binding to SA leads to a decrease in the free drug concentration and meanwhile an increase in the drug half-life. As this is the unbound fraction of a drug that exhibits biological activity, its binding to SAs can significantly alter the pharmacokinetics and pharmacological properties of the compound. Therefore, understanding the pattern and mechanism of the interaction of a drug with SA would be extremely important for clinical care and evaluation of the optimum dose and clearance of drug from the body.

As a hydrophilic antibiotic, neomycin has a low serum protein binding and, depending on the methods used for testing, its binding may be between 0% and 30%.

8,9

Therefore, the study of its SA interaction kinetics could be a challenging issue and the development of a fast and reliable analytical method that allows the measurement of neomycin-albumin interaction kinetics would be of great value. There are various methods for ligand-protein interaction studies such as UV–Vis, fluorescence and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy.

10-12

Surface plasmon pesonance (SPR) is a surface-sensitive label-free technique that offers voluble information about molecular interactions,

13,14

characterizing binding reactions,

6

measuring reaction kinetics,

15-17

thermodynamic parameters,

16

affinity constants,

18

etc with high sensitivity. Owing to these properties and abilities, SPR technology has rapidly become a standard tool within the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. It is possible to achieve a real-time monitoring and analysis of drug-protein interactions by SPR technology which makes it possible to obtain more detailed information about the binding process, such as the association and dissociation reaction kinetics. This information would be of great value in structure/activity relationship (SAR) studies within the drug discovery process. There is also no need for drug labeling for SPR studies; this not only reduces the time required for samples preparation for analysis but also removes the concern that a tag may alter the binding properties. In addition, it is possible to use the SPR sensor chips for several cycles of analysis without compromising their functionality, which is a desirable feature for high throughput screening studies.

The aims of the present study were to investigate the kinetic and thermodynamic interaction of neomycin with BSA using a SPR based method and to evaluate the ability of SPR to study the interaction of a drug with a low affinity to a protein. In addition, the binding sites of neomycin on BSA were estimated using molecular docking studies.

Materials and Methods

Materials

PBS solution, acetate buffer, BSA, neomycin sulfate, ethanolamine-HCl, N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), and N-ethyl- N-(3-diethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Carboxymethyl dextran (CMD) low density-modified gold surface chips were supplied from BioNavis Company (Tampere-region, Finland).

SPR measurements

All kinetic parameters were recorded with dual flow channels SPR device that uses the Kretscheman prism configuration (MP-SPR Navi 210A, BioNavis Ltd, Tampere-region, Finland).

BSA immobilization through amino coupling

BSA immobilization on the CMD Au chip was carried out as follows: after inserting CMD Au chip on SPR instrument, the whole device was rinsed with acetate buffer (10mM, pH 4.5). After attaining steady baseline in sensorgram, the chip surface was cleaned with NaCl (2M) and NaOH (0.1M) by injecting them to both channels for 3 minutes at flow rate of 30 μL/min. The chip surface was activated by mixing 0.05 M NHS and 0.2 M EDC (1:1) and injecting the mixture solution into the instrument at flow 30 μL/min for 7 minutes. For immobilization of BSA, its solution was injected (0.3 mg/mL) to channel 1, for 7 minutes and the acetate buffer was injected as the running buffer to channel 2 (reference channel). Finally, ethanolamine-HCl (1.0M) solution was injected to the CMD chip surface for blocking the non-specific binding.

17,19,20

Kinetic analysis of immobilized BSA interaction with neomycin

Various concentrations of neomycin (1-128 µM) in PBS buffer were injected at a flow rate of 30 µL/min for 3 minutes at pH 7.4. Since BSA was immobilized at one flow cell, both flow cells were used for sample injection and the flow cell without any BSA was used as reference. Regeneration process was not essential due to rapid dissociation of neomycin from BSA surface. The degree of neomycin binding to BSA was determined through measuring the SPR signal at the end of the dissociation phase.

Trace DrawerTM for SPR NaviTM was used for the rate constants, affinity and kinetic calculations of BSA interaction with neomycin. Before calculations in Trace Drawer, data was extracted with SPR NaviTM Data viewer software.

Thermodynamic analysis

The effect of temperature on neomycin binding to BSA was investigated to obtain the thermodynamic parameters of neomycin–BSA complex formation. SPR measurements were carried out at four different temperatures (298, 303, 308 and 313°K).

Molecular docking study

Molecular docking was carried out to estimate the binding sites in BSA. Herein, the known x-ray 3D structures of BSA and neomycin were extracted from pdb entry 4OR0 and 5IQE, respectively. The docking of neomycin into BSA was performed with the program AUTODOCK 4.2 Release 4.2.6. The lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) was used to perform an automated molecular docking. Default parameters were used, except for the number of generations, energy evaluations, docking runs, and maximum number of retries which were set to 27 000; 25 000 000; 200 and 10 000 respectively. A number of grid points in xyz were 126*126*126 separated by 0.7 Å at the middle of the protein.

21

Results

BSA immobilization

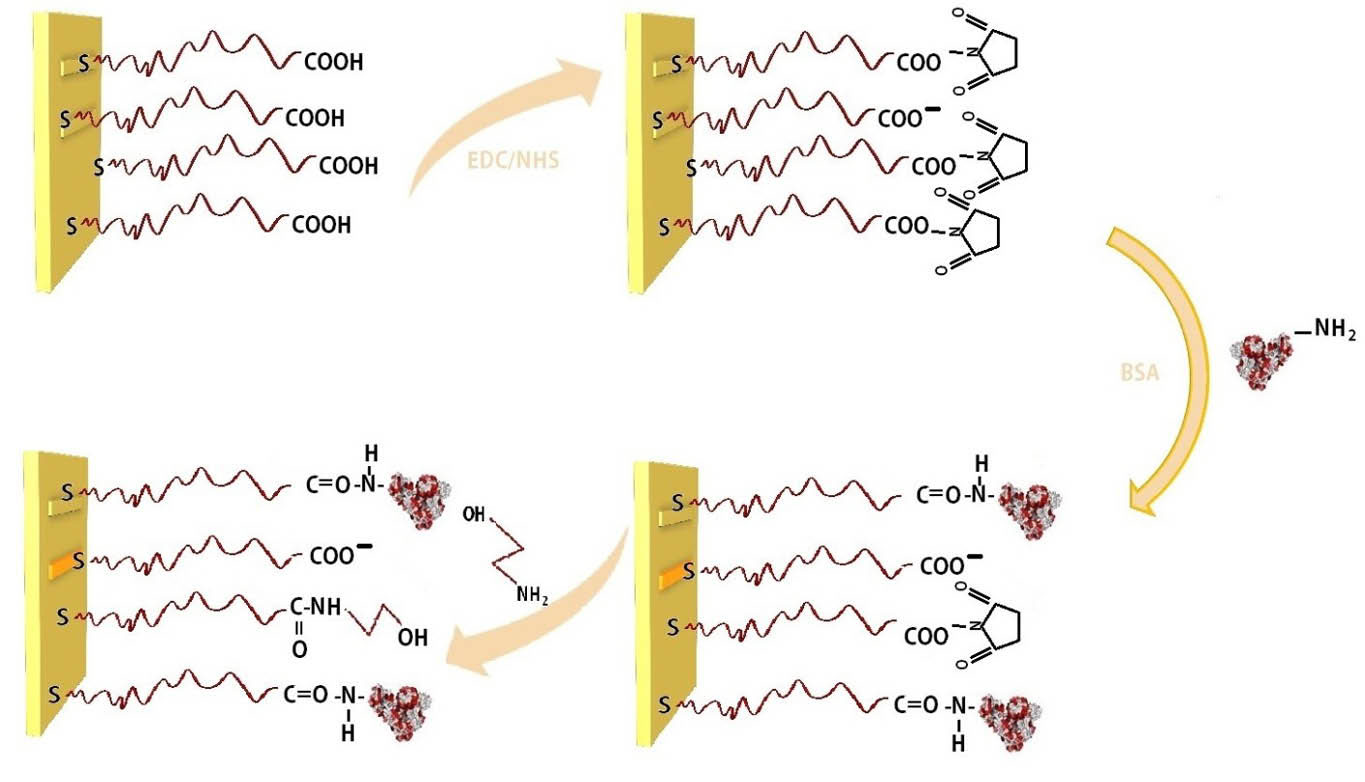

Schematic illustration of successful immobilization of the BSA through amine coupling on the sensor chip surface is shown in Fig. 2. After activation of carboxylic groups via EDC/NHS, BSA was adsorbed onto the CMD chip through covalent amide binding as described previously.

22

Finally, for blocking the unreacted sites of the surface, ethanolamine was used. Sensorgram measurements of these steps are shown in Fig. 3. As it is shown, the immobilization level and response unit (RU) of BSA at pH 7.4 were appropriate and acceptable. The immobilization process was further supported by indicating the shift in angular resonance after BSA immobilization.

Fig. 2.

. Schematic illustration of BSA immobilization by amine coupling: (1) carboxymethyl dextran sensor chip (2) Activation of COOH in

CMD via EDC/NHS. (3) Immobilization of the BSA. (4) Deactivation of the remaining activated surface groups by ethanolamines.

.

. Schematic illustration of BSA immobilization by amine coupling: (1) carboxymethyl dextran sensor chip (2) Activation of COOH in

CMD via EDC/NHS. (3) Immobilization of the BSA. (4) Deactivation of the remaining activated surface groups by ethanolamines.

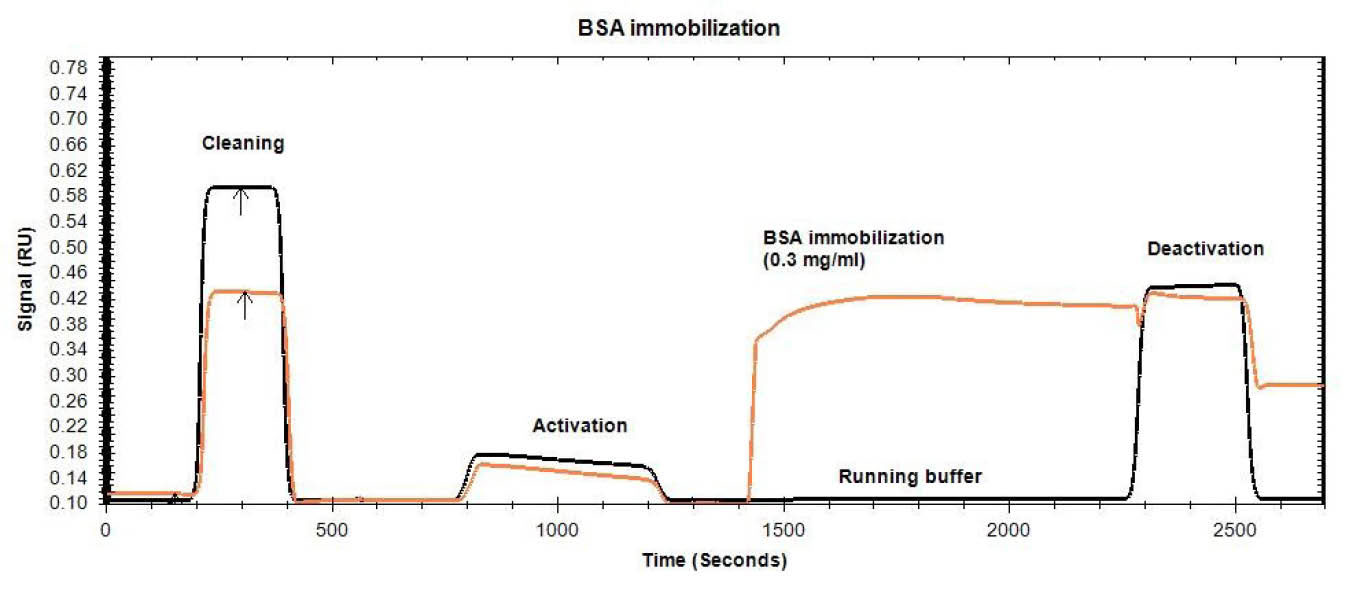

Fig. 3.

SPR sensogram of BSA immobilization process on a CMD chip (1- cleaning of the chip surface with NaCl (2 M) and NaOH (0.1 M)

2- chip surface activation through injection of NHS/EDC (1:1) mixture 3- immobilization of BSA on channel 1, 4- blocking of the non-specific

binding through ethanolamine-HCl (1.0M) solution injection).

.

SPR sensogram of BSA immobilization process on a CMD chip (1- cleaning of the chip surface with NaCl (2 M) and NaOH (0.1 M)

2- chip surface activation through injection of NHS/EDC (1:1) mixture 3- immobilization of BSA on channel 1, 4- blocking of the non-specific

binding through ethanolamine-HCl (1.0M) solution injection).

Neomycin-BSA interaction

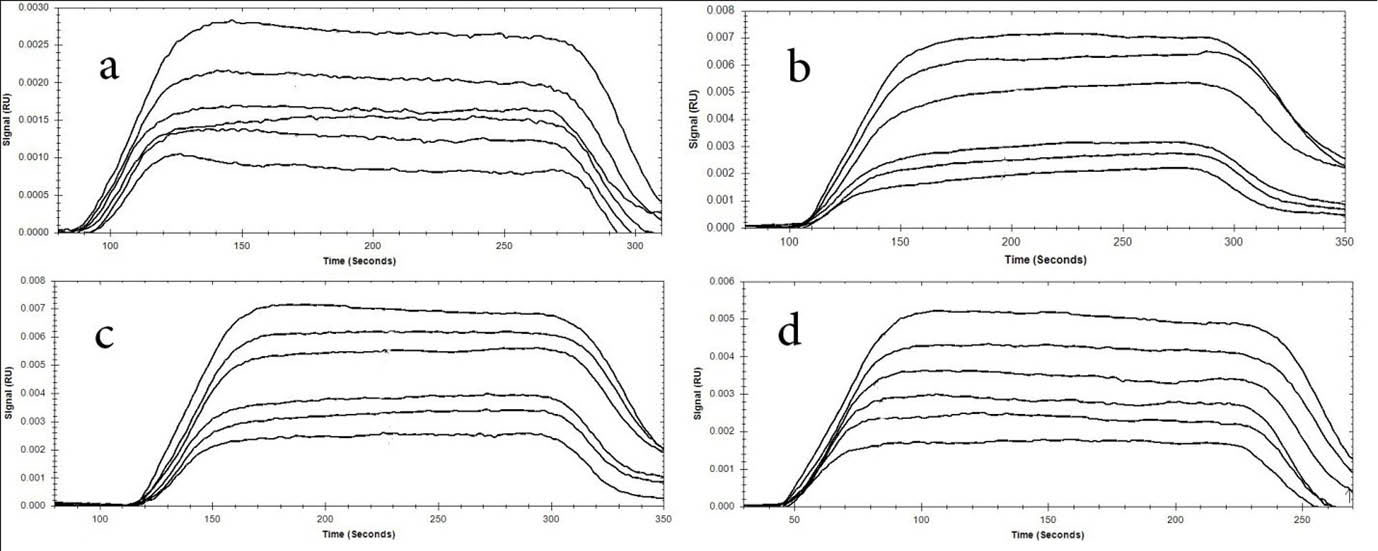

Fig. 4 shows the SPR curve of neomycin interaction with BSA at different concentrations ranging from 1 to 128 µM. Each concentration was injected to the immobilized BSA surface and the SPR signal was used for calculation after reference subtraction. For elimination and reducing of mass transport effect that results in inaccurate data, BSA molecule was immobilized at the low concentration and the flow rate of kinetic tests was set at a higher rate of 30 µL/min.

23

Dose-response sensorgrams were produced for the neomycin interaction with BSA confirming the results obtained from other methods such as spectroscopic (UV/VIS and fluorescence) studies.

Fig. 4.

Dose-response sensorgram of immobilized BSA interaction with neomycin at various concentrations (1-128 µ) at 4

temperatures (A) 298°K, (B) 303°K, (C) 308°K, and (D) 313°K.

.

Dose-response sensorgram of immobilized BSA interaction with neomycin at various concentrations (1-128 µ) at 4

temperatures (A) 298°K, (B) 303°K, (C) 308°K, and (D) 313°K.

Kinetics of BSA binding to neomycin

Kinetic parameters give information about how fast a given reaction will occur. The best fitting model adopted by the Trace DrawerTM software was a simple bimolecular reaction mechanism

. Association rate constant (ka) is the number of AB complexes formed per second and dissociation rate constant (kd) is the fraction of complexes that decay per second. Calculation of binding kinetic parameters is required for the estimation of ligand affinity for various biomacromolecules. To get the kinetic features, calculation of ka, kd

24

and the equilibrium constants (KD)

25

for the binding of BSA to neomycin are required. The affinity or equilibrium constant is a measure of the ligand tendency to biomacromolecules and defined as KD = kd/ka.

14

Table 1 shows values of aforementioned kinetic parameters at four temperatures. As it is shown in Table 1, ka and kd of interaction between BSA and neomycin increased regularly upon rising temperature.

Table 1.

Association rate (ka), dissociation rate (kd) and equilibrium constant (KD) values of neomycin interaction with BSA

|

T (K)

|

k

a

(1/M×s)

|

k

d

(1/s)

|

K

D

(M)

|

| 298 |

4.05×102

|

8.96×10-3

|

2.21×10-5

|

| 303 |

1.84×103

|

9.95×10-3

|

5.41×10-6

|

| 308 |

6.53×103

|

2.58×10-2

|

3.94×10-6

|

| 313 |

5.54×104

|

2.75×10-2

|

4.96×10-7

|

Thermodynamic analyses of BSA interaction with neomycin

Calculation of the thermodynamic parameters is required for estimation of binding force type. The plot of lnKD versus 1/T allows calculation of thermodynamic parameters of neomycin-BSA formation via van't Hoff equation (Eq. 1)

26,27

:

Knowing the enthalpy (∆H) and entropy (∆S) values, changes in Gibbs free energy (∆G) were calculated by the following standard equation (Eq. 2)

28,29

:

ΔG = ΔH −TΔS

The values of ΔH, ΔS and ΔG between neomycin and BSA interaction are presented in Table 2, which represent the type of reaction force. Negative values for both ΔH and ΔS were attained for interaction of BSA with neomycin.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic parameters of BSA interaction with neomycin at four different temperatures (298, 303, 308, 313°K)

|

T (K)

|

K

D

|

ΔH (kJ mol-1)

|

ΔS (J mol-1)

|

ΔG (J mol-1k-1)

|

| 298 |

2.21×10-5

|

|

|

3.83×102

|

| 303 |

5.41×10-6

|

-1.81×102

|

-6.97×102

|

4.33×102

|

| 308 |

3.94×10-6

|

|

|

4.83×102

|

| 313 |

4.96×10-7

|

|

|

5.34×102

|

Molecular docking study

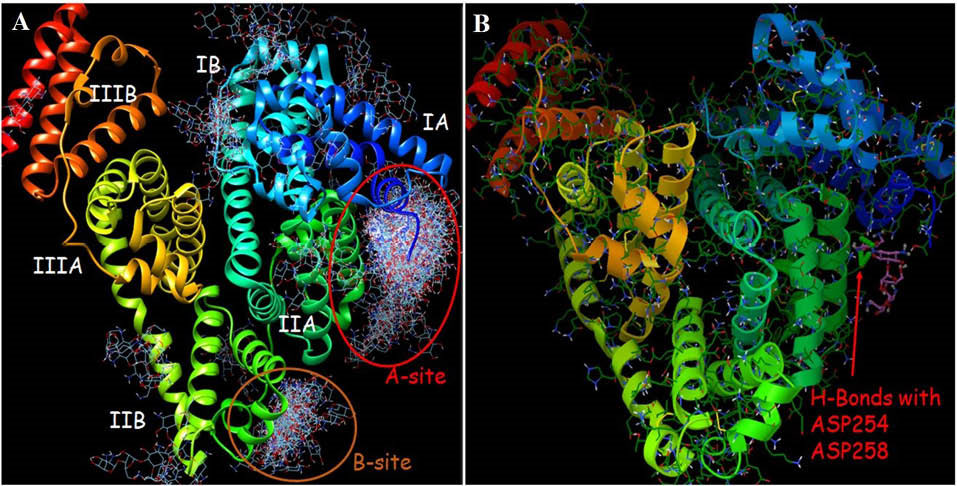

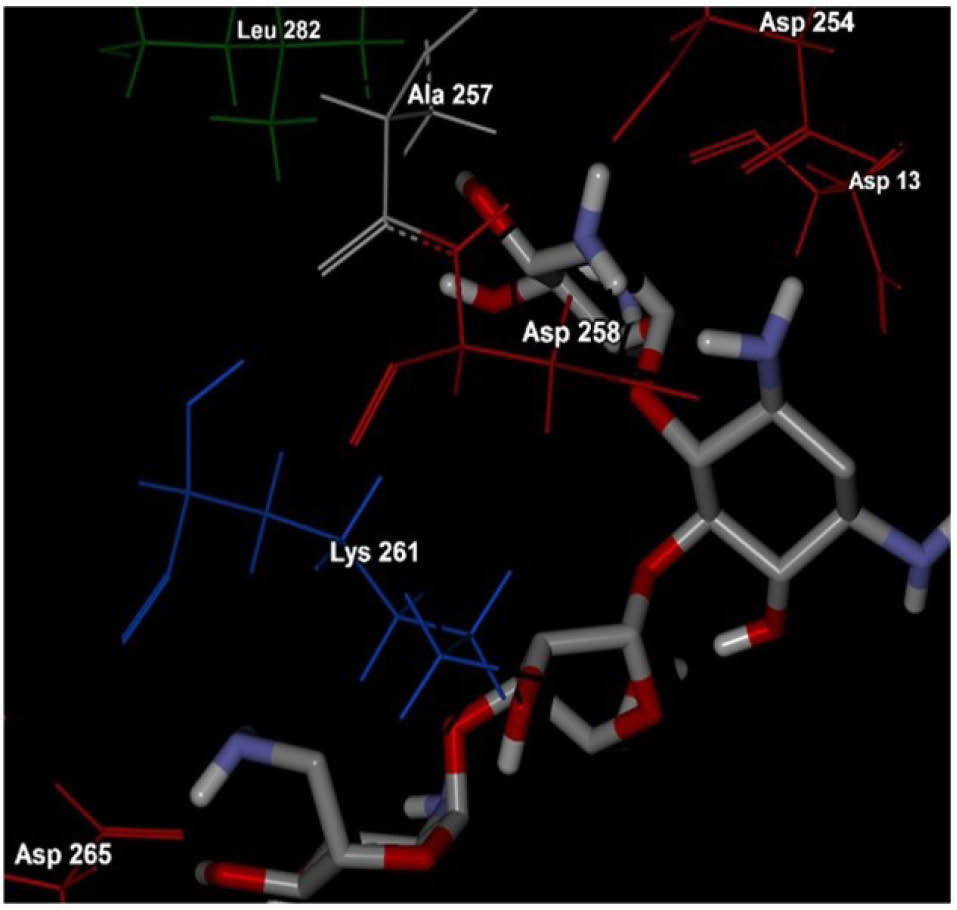

Molecular docking was used in order to identify the potential neomycin binding sites on BSA structure. The resulting docking energy and number of clustered neomycin conformations were provided in Table 3 and Fig. 5. Neomycin has capability to interact with all subdomains of BSA but most of the clustered neomycin (114 ligands) was found to be located in the A-site pocket corresponding to cleft of domain IA and IIA (Fig. 5). The orientation and H-bond interactions of the lowest estimated free energy of binding in first cluster of neomycin (-7.81 kcal/mol) were represented (Fig. 5). Besides, the attained results showed that ASP residues play a main role in the interaction of neomycin with BSA cleft between domain IA and IIA (Fig. 6).

Table 3.

Number of distinct conformational clusters out of 200 runs. LEbinding and MEbinding correspond to the lowest and mean binding energy in each clustera

|

Cluster rank

|

Cluster number

|

LE

binding

|

ME

binding

|

| 1 |

114 |

-7.81 |

-4.27 |

| 2 |

7 |

-7.15 |

-4.09 |

| 3 |

17 |

-6.85 |

-4.23 |

| 4 |

11 |

-5.35 |

-3.68 |

| 5 |

4 |

-5.06 |

-2.86 |

| 6 |

4 |

-3.72 |

-1.28 |

| 7 |

2 |

-3.6 |

-2.16 |

| 8 |

2 |

-3.56 |

-3.44 |

| 9 |

1 |

-3.41 |

-3.41 |

| 10 |

9 |

-3.29 |

-1.18 |

| 11 |

1 |

-3.09 |

-3.09 |

| 12 |

1 |

-2.71 |

-2.71 |

| 13 |

1 |

-2.49 |

-2.49 |

| 14 |

1 |

-2.22 |

-2.22 |

| 15 |

2 |

-2.17 |

-1.93 |

| 16 |

1 |

-2.01 |

-2.01 |

| 17 |

1 |

-1.93 |

-1.93 |

| 18 |

2 |

-1.93 |

-1.72 |

| 19 |

3 |

-1.83 |

0.05 |

| 20 |

1 |

-1.8 |

-1.8 |

| 21 |

1 |

-1.77 |

-1.77 |

| 22 |

1 |

-1.69 |

-1.69 |

| 23 |

1 |

-1.43 |

-1.43 |

| 24 |

1 |

-1.32 |

-1.32 |

| 25 |

1 |

-1.27 |

-1.27 |

| 26 |

1 |

-1.24 |

-1.24 |

| 27 |

1 |

-1.15 |

-1.15 |

| 28 |

1 |

-1.07 |

-1.07 |

| 29 |

1 |

-0.36 |

-0.36 |

| 30 |

1 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 31 |

1 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

| 32 |

1 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

| 33 |

1 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

| 34 |

1 |

0.72 |

0.72 |

| 35 |

1 |

1.46 |

1.46 |

aThe lowest docking-energy conformation was included in the largest cluster found. The rmsd-tolerance was applied at 5.0 Å.

Fig. 5.

(A) The resulting docked conformations were clustered

into families of similar binding modes, with a RMSD-clustering

tolerance of 5 Å. Two main clusters were achieved as indicated

A-site (114 conformers) and B-site (17 conformers). (B) Panel B is

representative of binding mode and possible H-bonds of the most

stable docked orientation of neomycin with BSA.

.

(A) The resulting docked conformations were clustered

into families of similar binding modes, with a RMSD-clustering

tolerance of 5 Å. Two main clusters were achieved as indicated

A-site (114 conformers) and B-site (17 conformers). (B) Panel B is

representative of binding mode and possible H-bonds of the most

stable docked orientation of neomycin with BSA.

Fig. 6.

The corresponding residues of the most stable docked

orientation of neomycin with BSA. As it is clear in the figure,

hydrophilic ASP residues play a main role in the interaction of

neomycin with BSA cleft between domain IA and IIA.

.

The corresponding residues of the most stable docked

orientation of neomycin with BSA. As it is clear in the figure,

hydrophilic ASP residues play a main role in the interaction of

neomycin with BSA cleft between domain IA and IIA.

Discussion

The SPR technique can be used for the investigation of protein structure change and protein–ligand complex formation. In the present study, we showed that the SPR signal enhanced upon increasing neomycin concentrations which approved the interaction of neomycin with BSA.

The attained kinetic study results indicate that the mean KD value for neomycin binding decreased almost 44.56 fold, from 22.1 µM to 0.496 µM over this temperature range. The temperature dependence of the KD was due to a larger increase in the ka value rather than the kd value. About 140-fold increase in the ka value was observed when temperature increased from 25°C to 40°C. However, there was only 3-fold increase in the kd value when temperature increased from 25°C to 40°C. Overall, the results of kinetic study showed that interaction of BSA with neomycin increases upon rising temperature.

6,30

The force of interaction between BSA protein and neomycin may be one of the following forces: hydrogen binding, Van der Waals, electrostatic, and hydrophobic forces, which can be estimated through thermodynamic parameters. If ΔH > 0 and ΔS > 0, the main forces are hydrophobic forces, the negative value of both ΔH and ΔS (ΔH < 0 and ΔS < 0) is demonstrative of Van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonds occurring and finally, if ΔH < 0 and ΔS > 0, the electrostatic interactions may be dominated.

31,32

Negative values of both ΔH and ΔS indicated that the BSA interacts with neomycin via Van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonds. Besides, the positive value of ΔG showed that the binding process was non-spontaneous and entropy driven and the formation of neomycin–BSA complex was an endothermic.

BSA is able to bind various ligands in several binding sites (I, II and III, which has two (A and B) subdomains). The exact BSA binding site for neomycin was cleft between subdomains IA and IIA. The results of this study showed that hydrogen bond is dominated force between BSA and neomycin due to the presence of hydrophilic amino acids such as aspartic acid.

11,33

Conclusion

In this work, we studied the interaction between BSA and neomycin and its related kinetic and thermodynamic parameters using SPR method. Kinetic study showed that the affinity of neomycin to BSA was high enough, which was confirmed by low value of KD. The results of thermodynamic parameters showed that the dominant forces between neomycin and BSA were Van der Waals and hydrogen bond forces due to hydrophilic characteristic of drug. Moreover, binding process is endothermic and entropy driven due to the positive value of ΔG. Molecular docking study confirmed that the dominated force between BSA and neomycin was through hydrogen bond due to the presence of hydrophilic amino acids at binding site of BSA.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

There is none to be declare.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful for financial support from Student Research Committee and Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

simple

-

√ Neomycin interacts with BSA through Van der Waals and

hydrogen bond forces and binding process is endothermic

and entropy driven due to the positive value of ΔG.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ For the first time, the interaction of neomycin with BSA

was investigated using SPR.

References

- Kahsay G, Song H, Van Schepdael A, Cabooter D, Adams E. Hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) in the analysis of antibiotics. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2014; 87:142-54. [ Google Scholar]

- de-los-Santos-Álvarez N, Lobo-Castañón MJ, Miranda-Ordieres AJ, Tuñón-Blanco P. SPR sensing of small molecules with modified RNA aptamers: detection of neomycin B. Biosens Bioelectron 2009; 24:2547-53. [ Google Scholar]

- Hu Y-J, Liu Y, Zhao R-M, Dong J-X, Qu S-S. Spectroscopic studies on the interaction between methylene blue and bovine serum albumin. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem 2006; 179:324-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2005.08.037 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jiang C-Q, Gao M-X, Meng X-Z. Study of the interaction between daunorubicin and human serum albumin, and the determination of daunorubicin in blood serum samples. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2003; 59:1605-10. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2011.07.066 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Naseri A, Hosseini S, Rasoulzadeh F, Rashidi M-R, Zakery M, Khayamian T. Interaction of norfloxacin with bovine serum albumin studied by different spectrometric methods; displacement studies, molecular modeling and chemometrics approaches. J Lumin 2015; 157:104-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2014.08.031 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fathi F, Dolatanbadi JEN, Rashidi M-R, Omidi Y. Kinetic studies of bovine serum albumin interaction with PG and TBHQ using surface plasmon resonance. Int J Biol Macromol 2016; 91:1045-50. [ Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh-Aghdash H, Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Dehghan P, Panahi-Azar V, Barzegar A. Multi-spectroscopic and molecular modeling studies of bovine serum albumin interaction with sodium acetate food additive. Food Chem 2017; 228:265-9. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.149 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Neomycin. http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00994.

- Keswani N, Choudhary S, Kishore N. Interaction of weakly bound antibiotics neomycin and lincomycin with bovine and human serum albumin: biophysical approach. J Biochem 2010; 148:71-84. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq035 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shahabadi N, Maghsudi M, Rouhani S. Study on the interaction of food colourant quinoline yellow with bovine serum albumin by spectroscopic techniques. Food Chem 2012; 135:1836-41. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.095 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tabassum S, Al-Asbahy WM, Afzal M, Arjmand F. Synthesis, characterization and interaction studies of copper based drug with Human Serum Albumin (HSA): Spectroscopic and molecular docking investigations. J Photochem Photobiol B 2012; 114:132-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.05.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Liu B, Li Z, Zhang L, Lv Y. Study of the combination reaction between drugs and bovine serum albumin with methyl green as a fluorescence probe. J Chem Pharm Res 2014; 6:968-74. [ Google Scholar]

- Green RJ, Frazier RA, Shakesheff KM, Davies MC, Roberts CJ, Tendler SJ. Surface plasmon resonance analysis of dynamic biological interactions with biomaterials. Biomaterials 2000; 21:1823-35. [ Google Scholar]

- Homola J. Surface plasmon resonance sensors for detection of chemical and biological species. Chem rev 2008; 108:462-93. [ Google Scholar]

- Lin M-S, Chiu H-M, Fan F-J, Tsai H-T, Wang SS-S, Chang Y. Kinetics and enthalpy measurements of interaction between β-amyloid and liposomes by surface plasmon resonance and isothermal titration microcalorimetry. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2007; 58:231-6. [ Google Scholar]

- McDonnell JM. Surface plasmon resonance: towards an understanding of the mechanisms of biological molecular recognition. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2001; 5:572-7. [ Google Scholar]

- Sharifi M, Dolatabadi JEN, Fathi F, Rashidi M, Jafari B, Tajalli H. Kinetic and thermodynamic study of bovine serum albumin interaction with rifampicin using surface plasmon resonance and molecular docking methods. J Biomed Opt 2017; 22:037002-

. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.22.3.037002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Myszka DG, Jonsen MD, Graves BJ. Equilibrium analysis of high affinity interactions using BIACORE. Anal Biochem 1998; 265:326-30. [ Google Scholar]

- Löfås S, Malmqvist M, Rönnberg I, Stenberg E, Liedberg B, Lundström I. Bioanalysis with surface plasmon resonance. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 1991; 5:79-84. doi: 10.1016/0925-4005(91)80224-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Johnsson B, Löfås S, Lindquist G. Immobilization of proteins to a carboxymethyldextran-modified gold surface for biospecific interaction analysis in surface plasmon resonance sensors. Anal Biochem 1991; 198:268-77. [ Google Scholar]

- Barzegar A, Moosavi-Movahedi AA, Mahnam K, Ashtiani SH. Chaperone-like activity of α-cyclodextrin via hydrophobic nanocavity to protect native structure of ADH. Carbohydr Res 2010; 345:243-9. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.11.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jordan CE, Corn RM. Surface Plasmon Resonance Imaging Measurements of Electrostatic Biopolymer Adsorption onto Chemically Modified Gold Surfaces. Anal Chem 1997; 69:1449-56. doi: 10.1021/ac961012z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Schuck P, Zhao H. The Role of Mass Transport Limitation and Surface Heterogeneity in the Biophysical Characterization of Macromolecular Binding Processes by SPR Biosensing. In: Mol JN, EMJ Fischer, editors. Surface Plasmon Resonance: Methods and Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2010. p. 15-54.

- Michelman-Ribeiro A, Mazza D, Rosales T, Stasevich TJ, Boukari H, Rishi V. Direct measurement of association and dissociation rates of DNA binding in live cells by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys J 2009; 97:337-46. [ Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Hoff KA, Hessen ET, Haug-Warberg T, Svendsen HF. Enthalpy of absorption of CO 2 with alkanolamine solutions predicted from reaction equilibrium constants. Chem Eng Sci 2009; 64:2027-38. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2008.12.037 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kashanian S, Dolatabadi JEN. DNA binding studies of 2-tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) food additive. Food Chem 2009; 116:743-7. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.03.027 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kashanian S, Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J. In vitro studies on calf thymus DNA interaction and 2-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol food additive. Eur Food Res Technol 2010; 230:821-5. doi: 10.1007/s00217-010-1226-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Banerjee R, Sarkar M. Direct binding of Cu(II)-complexes of oxicam NSAIDs with DNA backbone. J Inorg Biochem 2006; 100:1320-31. [ Google Scholar]

- Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Hamishehkar H, de la Guardia M, Valizadeh H. A fast and simple spectrofluorometric method for the determination of alendronate sodium in pharmaceuticals. Bioimpacts 2014; 4:39-42. doi: 10.5681/bi.2014.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Day YS, Baird CL, Rich RL, Myszka DG. Direct comparison of binding equilibrium, thermodynamic, and rate constants determined by surface- and solution-based biophysical methods. Protein Sci 2002; 11:1017-25. doi: 10.1110/ps.4330102 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rasoulzadeh F, Jabary HN, Naseri A, Rashidi M-R. Fluorescence quenching study of quercetin interaction with bovine milk xanthine oxidase. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2009; 72:190-3. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2008.09.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dolatabadi JEN, Panahi-Azar V, Barzegar A, Jamali AA, Kheirdoosh F, Kashanian S. Spectroscopic and molecular modeling studies of human serum albumin interaction with propyl gallate. RSC Adv 2014; 4:64559-64. doi: 10.1039/C4RA11103F [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Janati Fard F, Mashhadi Khoshkhoo Z, Mirtabatabaei H, Housaindokht MR, Jalal R, Eshtiagh Hosseini H. Synthesis, characterization and interaction of N,N′-dipyridoxyl (1,4-butanediamine) Co(III) salen complex with DNA and HSA. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2012; 97:74-82. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.05.066 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]