BioImpacts. 6(1):9-13.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2016.02

Original Article

Improvement of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation into the endoderm lineage by four step sequential method in biocompatible biomaterial

Saeed Azandeh 1, Anneh Mohammad Gharravi 2, Mahmoud Orazizadeh 1, *, Ali Khodadi 3, Mahmoud Hashemi Tabar 1

Author information:

1Cellular and Molecular Research Center (CMRC), Department of Anatomical Science, Faculty of Medicine, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (AJUMS), Ahvaz, Iran

2School of Medicine, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

3Cancer, Petroleum and Environmental Pollutants Research Center, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

The goal of the study described here, was to investigate the potential of umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cell (UC-MSCs) into hepatocyte like cells in a sequential 2D and 3D differentiation protocols as alternative therapy.

Methods:

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were isolated from the umbilical cord (UC) and CD markers were analyzed by flow cytometry. For hepatic differentiation of UC-MSCs, cells were induced with a sequential 4-step protocol in 3D and 2D culture system. Urea concentration and albumin secretion into the culture medium was quantified by ELISA. Gene expression levels of AFP, ALB, and CK18 were determined by RT-PCR. Data were statistically analyzed by the SPSS software. The difference between the mean was considered significant when p < 0.05.

Results:

Growth factor dependent morphological changes from elongated fibroblast-like cells to round epithelial cell morphology were observed in 2D culture. Cell proliferation analysis showed round-shaped morphology with clear cytoplasm and nucleus on the alginate scaffold in 3D culture. The mean valuses of albumin production and urea secretion were significantly higher in the 3D Culture system when compared with the 2D culture (p = 0.005 vs p = 0.001), respectively. Treatment of cells with TSA in the final step of differentiation induced an increased expression of CK18 and a decreased expression of αFP in both the 3D and 2D cultures (p = 0.026), but led to a decreased albumin gene expression, and an increased expression in the 2D culture (p = 0.001).

Conclusion:

Findings of the present study indicated that sequential exposure of UC-MSCs with growth factors in 3D culture improves hepatic differentiation.

Keywords: 3D culture, Liver, Mesenchymal stem cell, Umbilical cord

Copyright and License Information

© 2016 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Liver disease accounts for almost 2% of all deaths.

1

Many diseases can cause liver failure and severely impaire a person’s health and cause the need for a liver transplant. Although the liver transplant is viable and the only treatment for end stage liver diseases, the number of people waiting for transplantation is much larger than donors. Therefore, alternative therapies for liver disease are increasingly being used. Tissue engineering with stem cell provides a novel and alternative treatment for liver failures.

2

Since tissue engineering of stem cells has exhibited therapeutic effects, several researches have indicated that umbilical cord derived multipotent stem cells are capable of giving rise hepatocyte cells. In principle, most of these investigations are based on reconstructing the living environments in vivo.

3

One of the most frequently investigated scaffolds in liver tissue engineering is alginate. Biocompatibility and ability to form gel are great advantages of this biomaterial. Encapsulation of several stem cells has been used for providing environmentally liver tissue and creates hepatocyte like cells.

4

In previous studies, hepatic differentiation of different mesenchymal stem cell has been investigated. And several cocktail and sequential protocols have been examined.

5,6

Several liver tissue engineering methods have been performed under similar pro-hepatogenic conditions by sequential exposure or cocktail to cytokines, growth factors and hormones that reflect their temporal expression during in vivo hepatogenesis; however these studies have been conducted in the 2D culture condition.

7-10

We aimed to do hepatic differentiation of human MSCs according to an innovative method. Four-step sequential 3D culture of MSCs closely reflected in vivo condition. Therefore, the goal of the study described here, was to investigate the potential of umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells to turn into hepatocyte like cells based on a sequential 2D and scaffold-based 3D differentiation protocol.

Materials and methods

Materials

All materials and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA), BioAssay Systems (Hayward, CA, USA), Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA), and eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). All chemicals were used directly without further purification.

Umbilical cord was collected from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Imam Khomeini Hospital in Jundishapour University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran (AJUMS) in sterile transport medium. The medium contained DMEM (low glucose) with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 mg/mL amphotericin B. Collected Umbilical cords were stored at 4°C for 2-6 h before further processing.

11

MSCs isolation and expansion

Long pieces of Wharton’s jelly (2 – 4 mm) were placed in a 37°C incubator with humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The explants were cultured in the complete culture medium (CCM) containing DMEM (low glucose), 2 mM L-glutamine, supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 100 U penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were allowed to adhere to the culture flask. Approximately one week takes to reach cell confluence covering 70%-80% of the flask. Then, adherent cells were trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA in an incubator for 5 min at 37°C. Detached cells floating in the medium were centrifuged at 200-300 g for 10 min, cell pellets washed with 2 to 5 mL of fresh growth medium and the resuspended cells transferred to a 25 cm2 flask at a density 2.50 × 105 cells/cm2. During subculture, they were passaged every 5 days; the medium was replaced every 3-4 days or twice a week. The cells were subcultured when they were reached to a confluency of 80 to 90% (about 7-10 days).

11

Flow cytometry

After trypsinization and harvesting, 5.0 × 105 cells were analyzed for CD markers by flow cytometry. Briefly, cell were resuspended in PBS and 5% FBS was incubated with phycoerythrin (PE) - or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) -conjugated antibodies against CD73, CD31 and IgG (eBioscience,, USA) for 30 min in the dark at 4°C. Labeled cells were analyzed by Dako Galaxy flocwytometer. Mouse isotype-matched antibody (Ab) were used as controls (eBioscience,, USA).

11

Hepatic differentiation of UC-MSC in 3D culture system

For hepatic differentiation of UC-MSCs towards endodermal lineage, cells were induced with a sequential 4-steps protocol.

8

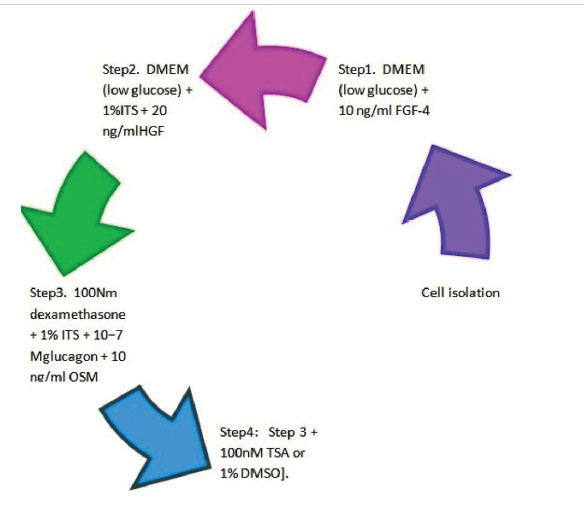

Briefly, UC-MSCs were seeded into 25-cm2 T-flasks at a density of 1.0×104 cells/cm2 and exposed to differentiation factors as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

.

Hepatic differentiation UC-MSCs with a sequential 4-step

protocol.

.

Hepatic differentiation UC-MSCs with a sequential 4-step

protocol.

At first, for MSCs encapsulation and preparation of 2.0% w/v alginate solution, alginic acid sodium salt was added into the 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.025 M HEPES in deionized water.

12

About 1.0 × 106 isolated cells from umbilical cord were mixed and resuspended in 2-5 mL prepared solution, and then dropped into a 102-mM CaCl2 solution. Encapsulated MSCs were polymerized for a period of 10 min in the CaCl2 solution and consequence alginate beads containing MSCs were formed. Then, the beads were washed 2-3 times with 10 volumes of 0.15 M NaCl. These tissue constructs were finally placed and cultured in 25-cm2 T-flasks with complete culture medium. Hepatic differentiation of UC-MSC was induced with a 4-step protocol as described above.

12

ELISA

Urea concentration and albumin secretion into the culture medium was quantified by urea and albumin assay kit and method according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Supernatants of culture medium were collected from each hepatic differentiation step.

8

PCR

At the end of hepatic differentiation, alginate beads containing hepatocytes like cell were depolymerized with EDTA, and cells were extracted. The resulting cells were assayed for the expression of characteristic markers.

Gene expression level of AFP, ALB, and CK18 were determined by RT–PCR. Primers were first designed using Primer Express 1.0a Software (Applied Biosystems) for ALB, AFP and CK-18.

8

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed by an SPSS software. The difference between the mean was considered significant based on a p value less than 0.05.

Results

Flow cytometry analysis

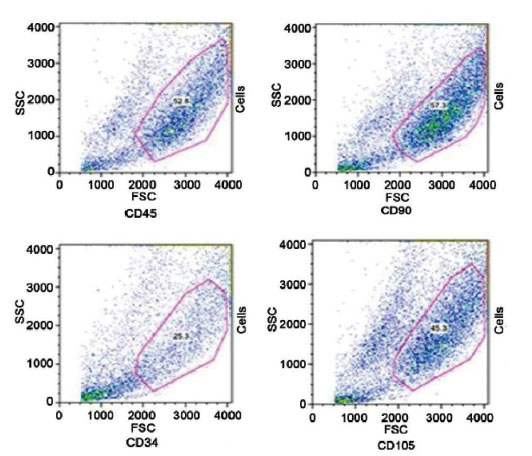

Cellular characterization and antigen expression profiles MSCs showed that looking at CD73 and CD31, the MSCs were positive for mesenchymal markers such as CD73. When MSCs were examined for haematopoietic stem cell (lineage negative cell fraction) recovery, the lineage negative population was characterized as the percentage of cells that were tested negative for CD31 on the flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

.

Flow cytometric analysis of MSCs surface antigens. MSCs express CD90 and CD105 but do not express CD34 and CD45 (hematopoietic markers).

.

Flow cytometric analysis of MSCs surface antigens. MSCs express CD90 and CD105 but do not express CD34 and CD45 (hematopoietic markers).

Morphology

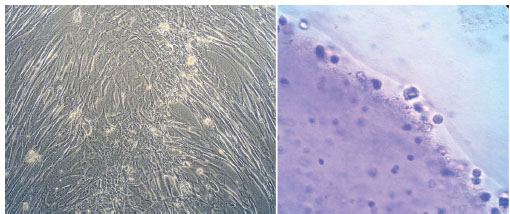

Isolated cells in the 2D culture initially displayed a fibroblast-like morphology, with the majority of the cells being flat with a wide cytoplasm. Rapid proliferation of fibroblast like cells led to cluster formation. When MSCs were exposed to four step differentiation protocol, growth factor dependent morphological changes from elongated fibroblast-like cells to round epithelial cell morphology were observed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

.

Inverted microscopy of MSCs during four steps sequential differentiation protocol in 2D (left and) 3D (right) cultures. Image magnification is 400 X.

.

Inverted microscopy of MSCs during four steps sequential differentiation protocol in 2D (left and) 3D (right) cultures. Image magnification is 400 X.

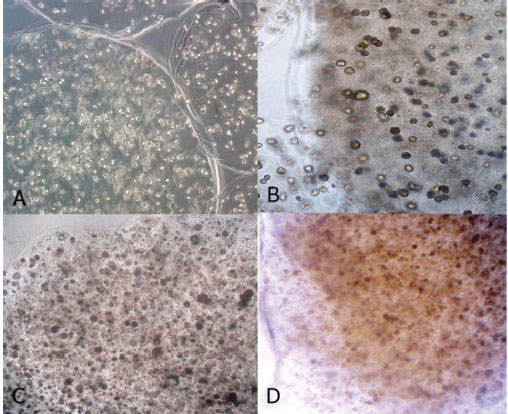

Cell proliferation with round-shaped morphology with clear cytoplasm and nucleus in the alginate scaffold was observed in the 3D culture. After treatment of cell with differentiation factors, cells were close together to form clusters which gradually increased. In the final step, TSA treated cells appeared to possess more compact cluster (Figs. 3 and 4) (Table 1).

Fig. 4

.

Inverted microscopy of MSCs during four steps sequential differentiation protocol in 3D culture. Morphological change of differentiated MSCs during 3D culture system is clearly visible. A(step1.), B(step1.), C(step1.), D(step1.) Image magnification is 400 X.

.

Inverted microscopy of MSCs during four steps sequential differentiation protocol in 3D culture. Morphological change of differentiated MSCs during 3D culture system is clearly visible. A(step1.), B(step1.), C(step1.), D(step1.) Image magnification is 400 X.

Table 1

.

Morphological change of UC-MSCs in 2D and 3D culture system in different steps of differentiation

|

Morphology

|

Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 3

|

Step 4

|

| 2D |

Cell proliferation suppresses

Elongate fibroblast-like cells

Cluster formation

Decrease cell size

|

Increase granularity

Increase cell size

Increase number of cell nuclei.

Flat shape.

|

Polygonal shape.

Increase Granularity and the number of cell nuclei

|

Decrease cell size. Rounded epithelial cell morphology |

| 3D |

Round shaped cell |

Round shape cell

|

Round shaped cell

Cluster formation

|

Round shaped cell

Cluster formation

|

Albumin secretion

Exposure of cells to different factors in the 3D culture system (FGF4 and HGF) induced albumin production activity and continued with further exposure to dexamethasone, glucagon, ITS and OSM at day 12. In the step 4, treatment of cells with the TSA decreased the production albumin was observed. Albumin production activity was observed in the 2D culture system 8 days after the treatment of cells with differentiation factors. There was a significant difference between the 2D and the 3D Culture system when ANOVA test was performed. The mean of albumin production was significantly higher in the 3D culture system as compared with the 2D culture (p = 0.005) (Table 2).

Table 2

.

Albumin production by differentiated UC-MSCs in 2D and 3D culture system (ng/mL)

|

Albumin production

|

Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 3

|

Step 4

|

| 2D |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

0.5 |

| 3D |

0.0 |

1.5 |

4.0 |

1.5 |

Urea secretion

Exposure of the cells to differentiation factors in the 3D culture system (FGF4) induced urea production activity and continued with further exposure to HGF, dexamethasone, glucagon, ITS and OSM. In the step 4, treatments of cells with TSA induced the maximum urea secretion activity. After two days, treatment of cells by FGF4 induced urea secretion in the 2D culture. Dexamethasone, glucagon, ITS and OSM led to the increase of urea secretion. The mean value of urea secretion was significantly higher in the 3D culture as compared with the 2D culture (p= 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3

.

Urea production by differentiated UC-MSCs in 2D and 3D culture system (ng/mL)

|

Urea secretion

|

Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 3

|

Step 4

|

| 2D |

4.0 |

4.0 |

8.0 |

12.0 |

| 3D |

13.0 |

12.0 |

14.0 |

15.0 |

Gene expression

In the final step, differentiated cells responded differently to the exposure with TSA. Treatment of cells with TSA in the final step of differentiation induced an increased expression of CK18 and a decreased expression of αFP (p = 0.026). Interestingly, exposure of cells in the 3D culture to TSA at day14 led to the decreased albumin gene expression while the increase in the 2D culture (p= 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4

.

Urea production by differentiated UC-MSCs in 2D and 3D culture system (ng/mL)

|

Culture

|

TSA

|

Alb

|

AFP

|

Ck18

|

| 2D |

-TSA |

1.87 |

5.30 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

1.88 |

5.40 |

0.02 |

|

|

|

1.85 |

5.25 |

0.12 |

| 2D |

+TSA |

3.73 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

3.74 |

0.12 |

0.13 |

|

|

|

3.71 |

0.99 |

0.97 |

| 3D |

-TSA |

3.73 |

8.60 |

0.03 |

|

|

|

3.72 |

8.70 |

0.04 |

|

|

|

3.70 |

8.57 |

0.29 |

| 3D |

+TSA |

0.001 |

5.30 |

9.85 |

|

|

|

0.002 |

5.35 |

9.87 |

|

|

|

0.003 |

3.27 |

9.83 |

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the hepatic differentiation UC-MSCs uses 3D biocompatible biomaterial to simulate in-vivo environment. Also results of in-vivo simulated the 3D culture were compared with conventional 2D culture system.

When MSCs in the 3D culture were exposed to the 4-step differentiation protocol, the shape of cell was constant as round with clear cytoplasm. Also, in the 2D culture there were growth factor dependent morphological changes from elongated fibroblast-like cells to rounded epithelial cell morphology. In previous studies, several investigators observed these results in their examination.

11-13

Biocompatible biomaterial could simulate the in-vivo environment partially.

When MSCs in the 3D culture exposed to four step differentiation protocol, FGF4 and HGF could induce albumin production activity. Also, Albumin production activity was observed in the 2D culture system 8 days after treatment of cells with differentiation factors.

The mean of albumin production was significantly higher in the 3D culture system when compared with 2D culture. Previous studies showed the role that TSA plays as proliferation inhibitor and differentiation-inducer agent,

7

therefore albumin production could be indicated in the early stage of differentiation.

14

Microenvironment created by the scaffold induces higher albumin production than the culture flask.

The mean of urea secretion in our study was significantly higher in the 3D culture when compared with the 2D culture. Our results are similar to other studies which conducted hepatic differentiation with sequential manner.

8,12

Treatment of cells with TSA in the final step of differentiation induced increased expression of CK18 and decreased expression of αFP. But exposure of cells in the 3D culture to TSA at day14 led to decreased albumin gene expression while decrease in the 2D culture. As mentioned above, previous studies showed the role of TSA as proliferation inhibitor and differentiation-inducer agent,

11

therefore MSCs exposed to hepatic differentiation factors, could induce the expression of different hepatocyte-specific markers of ALB, αFP, and CK18. Our results are similar to previous studies regrading gene expression following hepatocyte induction.

15

Conclusion

Altogether according to the constant round shape of MSCs, higher urea secretion and album is an indicator of the early stage of differentiation and expression of the hepatocyte-specific markers ALB, αFP and CK18 differently. The results of the present study show that sequential exposures of UC-MSCs with growth factors in the 3D culture improve hepatic differentiation.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapour University of Medical Sciences (AJUMS).

Competing interests

We have no conflicting interests with regard to the present submission.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Cellular and Molecular Research Center (CMRC), Research deputy of Ahvaz Jundishapour University of Medical Sciences.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

simple

-

√ In previous studies, hepatic differentiation mesenchymal stem cell has been investigated with cocktail and sequential protocols using a 2D culture.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ Sequential exposures of UC-MSCs with growth factors using a 3D culture can improve the differentiation of hepatic cells.

References

- Byass P. The global burden of liver disease: a challenge for methods and for public health. BMC Med 2014; 12:1. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0159-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ohashi K, Yokoyama T, Yamato M, Kuge H, Kanehiro H, Tsutsumi M. Engineering functional two-and three-dimensional liver systems in vivo using hepatic tissue sheets. Nature Med 2007; 13:880-5. doi: 10.1038/nm1576 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kulig KM, Vacanti JP. Hepatic tissue engineering. Transpl Immunol 2004; 12:303-10. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2003.12.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bachmann A, Moll M, Gottwald E, Nies C, Zantl R, Wagner H. 3D Cultivation Techniques for Primary Human Hepatocytes. Microarrays 2015; 4:64-83. doi: 10.3390/microarrays4010064 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Ruan Z, Yin Y, Chen G. Expression and Significance of DLL4-–Notch Signaling Pathway in the Differentiation of Human Umbilical Cord Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Cardiomyocytes Induced by 5-Azacytidine. Cell Biochem Biophys 2015; 71:249-53. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0191-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Liu Y, Jing Q, Zhang L. Differentiation of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells into hepatocytes in vitro. Biomed Mater Eng 2015; 25:145-57. doi: 10.3233/BME-141249 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Snykers S, De Kock J, Tamara V, Rogiers V. Hepatic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells: in vitro strategies. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Assays and Applications 2011:305-14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-999-4_23 [Crossref]

- Yoon HH, Jung BY, Seo YK, Song KY, Park JK. In vitro hepatic differentiation of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell. Process Biochem 2010; 45:1857-64. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2010.06.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Waclawczyk S, Buchheiser A, Flögel U, Radke TF, Kögler G. In vitro differentiation of unrestricted somatic stem cells into functional hepatic‐like cells displaying a hepatocyte‐like glucose metabolism. J Cell Physiol 2010; 225:545-54. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22237 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tamagawa T, Oi S, Ishiwata I, Ishikawa H, Nakamura Y. Differentiation of mesenchymal cells derived from human amniotic membranes into hepatocyte‐like cells in vitro. Human Cell 2007; 20:77-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-0774.2007.00032.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Ren H, Li X, Chen Z, Zhang X, Gong W. Differentiation of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells into low immunogenic hepatocyte-like cells. Cytotherapy 2009; 11:414-26. doi: 10.1080/14653240902849754 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lin N, Lin J, Bo L, Weidong P, Chen S, Xu R. Differentiation of bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells into hepatocyte‐like cells in an alginate scaffold. Cell Prolif 2010; 43:427-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00692.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mori Y, Ohshimo J, Shimazu T, He H, Takahashi A, Yamamoto Y. Improved explant method to isolate umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells and their immunosuppressive properties. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods 2015; 21:367-72. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2014.0385 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Maguire T, Davidovich AE, Wallenstein EJ, Novik E, Sharma N, Pedersen H. Control of hepatic differentiation via cellular aggregation in an alginate microenvironment. Biotechnol Bioeng 2007; 98:631-44. doi: 10.1002/bit.21435 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghaedi M, Soleimani M, Shabani I, Duan Y, Lotfi AS. Hepatic differentiation from human mesenchymal stem cells on a novel nanofiber scaffold. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2012; 17:89-106. doi: 10.2478/s11658-011-0040-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]