BioImpacts. 7(4):255-261.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2017.30

Original Research

Association of glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms with the severity of mustard lung

Arash Hajizadeh Dastjerdi 1, Hossein Behboudi 1, Zahra Kianmehr 2, Ali Taravati 3, Mohammad Mehdi Naghizadeh 4, Sussan Kaboudanian Ardestani 1, *, Tooba Ghazanfari 5, *

Author information:

1Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, North Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

3Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, Faculty of Basic Sciences, University of Mazandaran, Babolsar, Iran

4Noncommunicable Diseases Research Center, Fasa University of Medical Science, Fasa, Fars Province, Iran

5Immunoregulation Research Center, Shahed University, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) is one of the major detoxifiers in alveoli. Polymorphism in GST genes can influence the ability of individuals to suppress oxidative stress and inflammation. The present study was aimed to explore the hypothesis that the genetic polymorphisms of GST T1, M1 and P1 are associated with the severity of the mustard lung in the sulfur mustard-exposed individuals.

Methods:

Blood samples were taken from 185 sulfur mustard-exposed and 57 unexposed subjects. According to the stage of the mustard lung, sulfur mustard-exposed patients were categorized in the mild/moderate and severe/very severe groups. A multiplex PCR method was conducted to identify GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes. To determine the polymorphisms of GSTP1 in exon 5 (Ile105Val) and exon 6 (Ala114Val), RFLP-PCR method was performed.

Results:

The frequency of GSTM1 homozygous deletion was significantly higher in the severe/very severe patients compared with the mild/moderate subjects (66.3% vs. 48%, P = 0.013). The GSTM1 null genotype was associated with the severity of mustard lung (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.257; 95% CI, 1.219-4.180). There was no significant association between GSTT1 and GSTP1 polymorphisms with the severity of the mustard lung.

Conclusion:

The different distribution of GSTM1 null genotype in severe/very severe and mild/moderate groups indicated that the severity of the mustard lung might be associated with the genetic polymorphism(s).

Keywords: Glutathione S-transferase, GSTM1 null genotype, Mustard lung, Polymorphism, Pulmonary complications

Copyright and License Information

© 2017 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Sulfur mustard or 1-chloro-2-(2-chloroethylsulfanyl) ethane as an alkylating agent can induce a special type of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is called “mustard lung”.

1,2

The mustard lung begins with the acute bronchitis and airway hyperreactivity, then continues to form some long-term respiratory complications, which persist throughout the lifetime of most cases. Understanding the molecular mechanism of the mustard lung and the triggers of its severity is thus crucial to restrict the respiratory complications. Individuals exposed to sulfur mustard, develop ongoing lung inflammation and an imbalance in oxidant/antioxidant systems.

3-5

For example, evaluation of inflammatory chemokines has indicated the elevated level of some acute and chronic inflammatory mediators in these individuals.

6,7

Inflammation and oxidative stress-related disabilities are associated with genetic variation.

8-11

Thus, the evaluation of genetic variations in patients with different severity of mustard lung may provide helpful evidence to address its underlying molecular mechanism.

Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) as a detoxifying family of enzymes modulate the addition of glutathione to oxidative stress products. These enzymes are involved in the incidence of oxidative stress and inflammatory-related diseases for various reasons. Firstly, several GST genes are polymorphic and their allelic variations can affect disease susceptibility.

12-14

Secondly, they detoxify a wide range of structurally different substrates produced through oxidative stress.

15

For example, peroxides produced from lipids, DNA, and catecholamines are neutralized by GST enzymes.

16

GSTs are also involved in intracellular signal transduction to regulate inflammation and oxidative stress signaling pathways.

17,18

According to their genetic sequences and amino acid content, the mammalian GSTs have been classified into seven distinct classes. These classes and their OMIM accession number are as follows: alpha (e.g., GSTA1; 138359), mu (GSTM1; 138350), kappa (GSTK1; 602321), theta (e.g., GSTT1; 600436), pi (GSTP1; 134660), omega (GSTO2; 605482), and zeta (GSTZ1; 603758). The main contribution of this study is to evaluate the association between the severity of mustard lung and some of GST polymorphisms. The studied variations were GSTM1 null genotype (GenBank accession no. X68676), GSTT1 null genotype (GenBank accession no. AP000351) and GSTP1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) including Ile105Val (rs1695) and Ala114Val (rs1138272).

Materials and Methods

Materials

All standard chemicals for DNA extraction, including EDTA, NAOH pellets, Tris base, HCl, MgCl2, Triton X100, sucrose, NaCl, sodium dodecyl sulfate, and sodium perchlorate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). Primers were obtained from Pishgam Biotech Company (Iran). PCR master mix (2X) was provided by Ampliqon (Denmark). GelRedTM Nucleic Acid Gel Stain was purchased from Biotium (USA). Agarose, Alw26I and AciI restriction enzymes, RFLP reagents, and DNA ladder were obtained from Thermo Scientific (USA).

Study design and participants

The study was performed on 185 male Iranian subjects with long-term respiratory complications 25 years after exposure to sulfur mustard. About 57 unexposed male subjects with mean age of 41.9 ± 9.6 were also used as the control. GOLD spirometric criteria based on FEV1 and FVC was employed to determine the severity of the disease.

19

The sulfur mustard-exposed population was classified in the severe/very severe (83 cases) and the mild/moderate (102 cases) groups based on mustard lung severity. The mean age of the severe/very severe group was 46.2 ± 7.9. There was no significant difference with mild moderate group (45.6 ± 7.2, P = 0.59). All participants provided informed consent prior to admission into the study.

Blood collection and DNA extraction

Blood samples were obtained from each participant in fasting state and collected in Na-EDTA coated tubes. DNA isolation was carried out using salting out method.

20

The isolated DNA was quantified by measuring absorbance at 260 and 280 nm.

Genetic analysis

GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes were determined in a single assay by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique.

21

The forward and reverse primers used were 5′GAACTCCCTGAAAAGCTAAAGC3′ and 5′ GTTGGGCTCAAATATACGGTGG 3′ for GSTM1 null genotype; 5′ TCACCGGATCATGGCCAGCA 3′ and 5′TTCCTTACTGGTCCTCACATCTC 3′ for GSTT1 null genotype; 5′ GAACTGCCACTTCAGCTGTCT 3′ and 5′ CAG CTGCATTTGGAAGTGCTC 3′ for CYP1A1 gene. Co-amplification of CYP1A1 gene was carried out to document successful PCR amplification. PCR was accomplished in a final volume of 20 μL containing 50ng isolated DNA, 10 pmol of each primer, and 10 μL 2X PCR master mix with 1.5 mM MgCl2. Amplification was conducted as follows: initial denaturation step for 5 minutes at 95ºC, followed by 30 cycles at 94ºC for 30 seconds, 61.5ºC for 30 seconds, 72ºC for 30 seconds, and a final extension step at 72ºC for 5 minutes. The PCR products from co-amplification of GSTTl, GSTMl and CYPlAl genes were then analyzed by electrophoresis on 2% Agarose gels stained with GelRedTM.

In GSTP1 gene 2 polymorphic sites (Ile105 → Val105; Ala114 → Val114) were assessed. For GSTP1 105Val variant, RFLP-PCR was performed according to Harries et al.

22

The forward and reverse primers used were 5′ ACC CCA GGG CTC TAT GGG AA 3′ and 5′ TGA GGG CAC AAG AAG CCC CT 3′, respectively. In a total volume of 20 μL, isolated DNA (50 ng) was used as an amplification template together with 10pmol of each primer and 10 μL 2X PCR master mix with 1.5 mM MgCl2. Amplification was carried out with a primary denaturation step at 95ºC for 5 minutes, continued with 30 cycles at 94ºC for 30 seconds, 55ºC for 30 seconds, 72ºC for 30 seconds, and a final extension step at 72ºC for 5 minutes. The digestion of PCR product accomplished using 5 units of Alw26I, in a total volume of 20 μL. The digested products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 3.5% Agarose gels.

For determining GSTP1 114Ala variant, RFLP-PCR was performed according to a method described by Ishii et al.

9

The forward and reverse primers used were 5' GGGAGCAAGCAGAGGAGAAT 3′ and 5' CAGGTTGTAGTCAGCGAAGGAG 3′, respectively. In a total volume of 20 μL, isolated DNA (50 ng) was used as an amplification template together with 10pmol of each primer and 10 μL 2X PCR master mix with 1.5 mM MgCl2. Amplification was carried out with a primary denaturation step at 95ºC for 5 minutes, continued with 30 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 minutes. The PCR product was digested using 5 units of AciI in a total volume of 20 μL. The digested products were analyzed using electrophoresis on 3.5% Agarose gels.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was used to explore the distribution of genotypes in 3 groups. Furthermore, the odds ratio was calculated between mild/moderate and severe/very severe groups to determine the risk of mustard lung severity in different genotypes. PFT parameters were compared between study groups with the t test. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and the frequency (percentage). All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The demographic characteristics of patients with severe/very severe and mild/moderate symptoms are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and age distribution in sulfur mustard-exposed patients

|

|

|

Pulmonary Assessment (GOLD)

|

|

Mild/Moderate

|

Severe/Very Severe

|

P

Value

|

|

No.

|

%

|

No.

|

%

|

| Chronic cough |

No |

5 |

4.9% |

3 |

3.6% |

0.669 |

|

|

Yes |

97 |

95.1% |

80 |

96.4% |

|

| Sputum |

No |

14 |

13.7% |

12 |

14.5% |

0.887 |

|

|

Yes |

88 |

86.3% |

71 |

85.5% |

|

|

|

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD

|

|

| Age (y) |

|

45.6 |

7.2 |

46.2 |

7.9 |

0.59 |

| FVC (%) |

|

89.26 |

6.08 |

55.9 |

5.07 |

<0.001 |

| FEV1 (%) |

|

59.07 |

4.05 |

32.67 |

4.7 |

<0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) |

|

66.5 |

6.6 |

57 |

9.7 |

<0.001 |

GSTM1 and GSTT1 gene polymorphisms

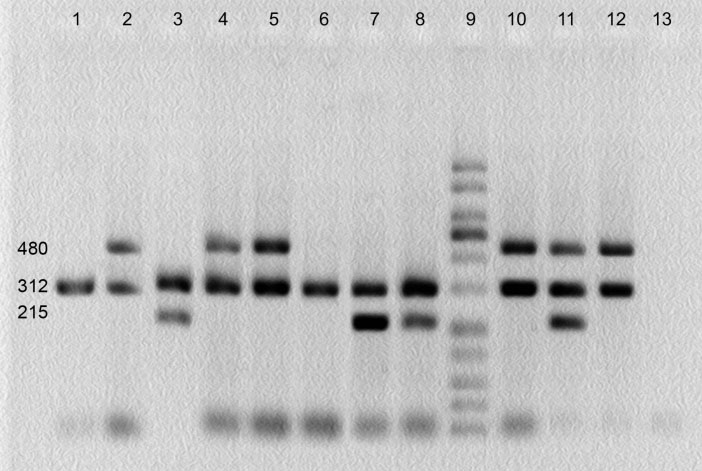

GSTMl and GSTTl genotypes were detected by the presence or absence of a band at 480 bp (corresponding to GSTTl gene) and a band at 215 bp (corresponding to GSTMl gene). A band at 312 bp (corresponding to CYPlAl gene) was used as an internal control (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Multiplex PCR products of GSTM1 and GSTT1 gene polymorphisms on agarose gel. Bands at 480, 215 and 312 bp correspond to GSTTl, GSTMl and CYPlAl genes, respectively. Lanes 1and 6: GSTM1 and GSTT1 simultaneous homozygous deletion; lanes 2, 4, 5, 10 and 12: GSTM1 homozygous deletion; lanes 3, 7 and 8: GSTT1 homozygous deletion; lane 9: molecular weight ladder; lane 13: negative control.

.

Multiplex PCR products of GSTM1 and GSTT1 gene polymorphisms on agarose gel. Bands at 480, 215 and 312 bp correspond to GSTTl, GSTMl and CYPlAl genes, respectively. Lanes 1and 6: GSTM1 and GSTT1 simultaneous homozygous deletion; lanes 2, 4, 5, 10 and 12: GSTM1 homozygous deletion; lanes 3, 7 and 8: GSTT1 homozygous deletion; lane 9: molecular weight ladder; lane 13: negative control.

The distributions of GST genotypes were explored to evaluate the probable association between genetic variation in GST genes and the severity of pulmonary complications. In the case of GSTM1, the frequency of homozygous null genotype in severe/very severe patients was 66.3% in comparison with mild/moderate individuals (48%) and unexposed subjects (57.9%), (P = 0.044), (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 genotypic frequencies in sulfur mustard-exposed patients and non-exposed individuals

|

Gene polymorphisms

|

Unexposed

|

Mild-moderate

|

Severe-very severe

|

P

a

|

P

b

|

P

c

|

P

d

|

P

e

|

OR

f

|

AOR

f

|

95% CI

|

|

No.

|

%

|

No.

|

%

|

No.

|

%

|

|

GSTM1 genotype

|

-/- |

33 |

57.9 |

49 |

48.0 |

55 |

66.3 |

0.044g

|

0.233 |

0.314 |

0.823 |

0.013g

|

2.125g

|

2.257g

|

1.219-4.180g

|

|

|

-/+ or +/+ |

24 |

42.1 |

53 |

52.0 |

28 |

33.7 |

|

GSTT1 genotype

|

-/- |

10 |

17.5 |

25 |

24.5 |

15 |

18.1 |

0.450 |

0.39 |

0.936 |

0.506 |

0.290 |

0.679 |

0.676 |

0.322-1.419 |

|

|

-/+ or +/+ |

47 |

82.5 |

77 |

75.5 |

68 |

81.9 |

|

GSTP1 Ile105Val

|

II |

24 |

43.9 |

42 |

41.2 |

39 |

47 |

0.896 |

0.899 |

0.745 |

0.871 |

0.666 |

0.790 |

0.695 |

0.237-2.042 |

|

|

IV |

28 |

49.1 |

51 |

50 |

36 |

43.4 |

|

|

VV |

4 |

7.0 |

9 |

8.8 |

8 |

9.6 |

|

GSTPAla114Val

|

AA |

50 |

87.7 |

86 |

83.5 |

68 |

81.9 |

0.648 |

0.474 |

0.355 |

0.376 |

0.778 |

1.116 |

0.843 |

0.388-1.831 |

|

|

AV |

7 |

12.3 |

17 |

16.5 |

15 |

18.1 |

|

GSTM1 and GSTT1 combinational genotype

|

M1-/-and T1-/- |

34 |

59.6 |

61 |

59.8 |

62 |

74.7 |

0.069 |

0.985 |

0.059 |

0.344 |

0.033g

|

1.98g

|

2.058g

|

1.099-3.953g

|

|

|

other |

23 |

40.4 |

41 |

40.2 |

22 |

25.3 |

Abbreviation: AOR: Adjusted odds ratio adjusted by age.

a comparison of 3 groups; b comparison of mild-moderate individuals with unexposed individuals; c comparison of severe-very severe individuals with unexposed individuals; d comparison of exposed and unexposed individuals; e comparison of severe-very severe individuals with mild-moderate subjects. f comparison of severe-very severe individuals with mild-moderate subjects. g data show significant differences with P < 0.05.

Comparing the 2 sulfur mustard-exposed groups for GSTM1 polymorphism indicated that the carriers of homozygous null genotype were more likely to develop the severe and very severe form of pulmonary complications (P= 0.013; adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.257; 95% CI, 1.219-4.180), (Table 2). The association between GSTM1 null genotype and the presence of symptoms like a chronic cough and sputum was also explored. However, there was no statistical association between GSTM1 null genotype with sputum (P = 0.793) and chronic cough (P = 0.717), (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of GSTM1 genotype with sputum and chronic cough in exposed population

|

|

|

Sputum

|

P

value

|

Chronic Chough

|

P

value

|

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

n

|

%

|

n

|

%

|

n

|

%

|

n

|

%

|

|

GSTM1 genotype

|

-/- |

14 |

53.8 |

90 |

56.6 |

0.793 |

4 |

50.0 |

100 |

56.5 |

0.717 |

| +/- or +/+ |

12 |

46.2 |

69 |

43.4 |

4 |

50.0 |

77 |

43.5 |

The frequencies of GSTT1-null genotype in severe/very severe, mild/moderate and unexposed groups were 18.1%, 24.5%, and 17.5%, respectively. Although there was a 6.5 percent statistical difference between 2 exposed groups, it was not significant (adjusted OR, 0.676; 95% CI, 0.322-1.419). A combinational study of GSTM1- and GSTT1-null genotypes was also conducted. Although the association among 3 groups in the combinational study was of borderline statistical significance (P= 0.069), the comparison of severe/very severe subjects with mild/moderate patients indicated the elevated risk of pulmonary complications (adjusted OR: 2.058, when 95% CI, 1.099-3.953, P = 0.033), (Table 2).

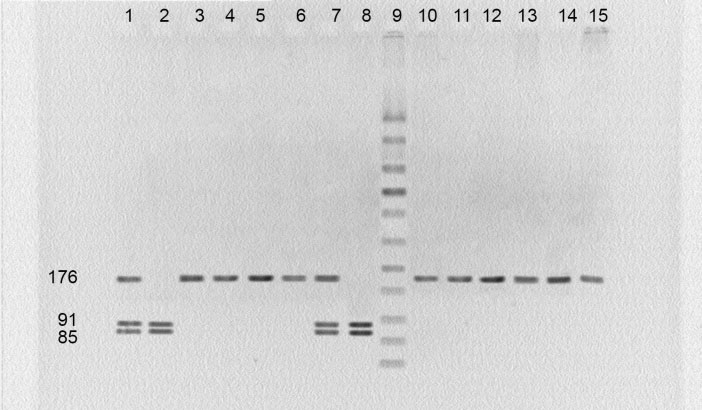

GSTP1 gene polymorphisms

The Ile105Val transition occurs within the exon 5 of GSTP1 gene. The digestion of PCR product determined 3 different genotypes in this region (Ile/Ile, Ile/Val and Val/Val). The presence of a single 176 bp band indicates the wild-type genotype (Ile/Ile), whereas the conversion of Ile to Val results in 3 bands of 176, 91 and 85 bp in heterozygotes and 2 bands of 91 and 85 bp in homozygotes (Fig. 2). Statistical differences among these genotypes were negligible. For example, the percentage of Ile/Ile genotype was determined as 47%, 41.2%, and 43.9% for severe/very severe, mild/moderate and unexposed groups, respectively. Consequently, the association between severity of pulmonary complications and the Ile105Val polymorphism was not significant (adjusted OR: 0.695; 95%CI, 0.237- 2.042), (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

PCR-RFLP assay for identification of polymorphism at GSTP1 Ile 105 residue. Lanes 3-6 and 10-15: Ile/Ile; lanes 1 and 7: Ile /Val; lanes 2 and 8: Val /Val; lane 9: molecular weight ladder.

.

PCR-RFLP assay for identification of polymorphism at GSTP1 Ile 105 residue. Lanes 3-6 and 10-15: Ile/Ile; lanes 1 and 7: Ile /Val; lanes 2 and 8: Val /Val; lane 9: molecular weight ladder.

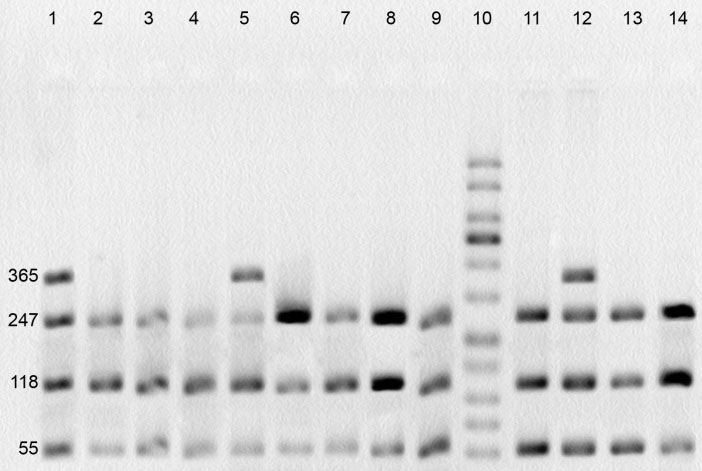

The Ala114Val variation occurs within the exon 6 of GSTP1 gene. The digestion of PCR product revealed 2 genotypes in this region (Ala/Ala and Ala/Val). The wild-type genotype (Ala/Ala) presents 2 recognition sites and creates 3 separated fragments (55, 118 and 247 bp). The conversion of Ala to Val removes one of the recognition sites and consequently, creates 2 fragments (55 and 365 bp) in homozygotes and 4 fragments (55, 118, 247 and 365 bp) in heterozygotes (Fig. 3). Val/Val genotype was absent in this study.

Fig. 3.

PCR-RFLP assay for identification of polymorphism at GSTP1 Ala114 position. Lanes 1, 5 and 12: Ala/Val genotype; lanes 2-4, 6-9, 11, 13 and 14: Ala/Ala genotype; lane 10: molecular weight ladder.

.

PCR-RFLP assay for identification of polymorphism at GSTP1 Ala114 position. Lanes 1, 5 and 12: Ala/Val genotype; lanes 2-4, 6-9, 11, 13 and 14: Ala/Ala genotype; lane 10: molecular weight ladder.

The prevalence of Ala/Ala homozygous genotype in the severe/very severe group was determined 81.9% in comparison with mild/moderate (83.5%) and unexposed groups (87.7%). There was no significant statistical difference between the studied groups (adjusted OR: 0.843; 95% CI, 0.388-1.831, p= 0.778), (Table 2).

Discussion

The mustard lung is the main long-term complication in sulfur mustard-exposed individuals. The difference in the severity of the mustard lung (mild, moderate, severe and very severe symptoms) suggests the involvement of genetic polymorphism in its appearance. To prove such scenario, the evaluation of polymorphism through oxidative stress and inflammation-related genes seems to be necessary. Polymorphisms of GST family play an important role in susceptibility to oxidative stress and inflammation-related disorders such as COPD,

9

rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

11

and multiple sclerosis (MS).

10

GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes were 2 of the selected polymorphisms in this study. Individuals with GSTM1 or GSTT1 deletion represent a complete loss of gene function.

23, 24

Polymorphisms of these xenobiotic metabolic genes (GSTM1 and GSTT1) induce mutation in several cancers such as breast cancer.

25

These genes are also related to detoxification of lipid and DNA hydroperoxides. This is specifically important because sulfur mustard derivatives trigger the formation of lipid peroxidation biomarkers such as malondialdehyde.

26,27

In addition, GSTM1 modulates signaling through interaction and inhibition of ASK1 (apoptosis signaling kinase 1).

17

This protective mechanism can preserve cells and is necessary to restrict oxidative stress. ASK1 is a MAP3K and acts through JNK and p38 signaling pathways, which respond to different stresses such as ROS and also regulate inflammation, morphogenesis and apoptosis.

18

Other studied polymorphisms were Ile105Val and Ala114Val within exon 5 and 6 of GSTP1 gene. Isoleucine to Valine substitution at codon 105 does not change the enzymatic affinity for glutathione.

28

However, electrophile substrate and its bulkiness can affect the efficiency of catalytic reaction.

29

Thermal stability of the Val 105 variant is also 2.5 fold higher than the Ile 105 variant. The residue 114 (Ala) is located in a position far from the active site, and its variation effects are unclear exactly.

In the current study, obtained results revealed that the GSTM1 null genotype frequency was 18% higher in severe/very severe patients in comparison with mild/moderate individuals. The frequency of GSTM1 null genotype was determined 58% in unexposed group, which is consistent with other studies in Iranian population.

30

The frequencies of homozygous null genotype in severe/very severe patients (66.3%) and mild/moderate population (48%) indicate the different distribution of genotypes in 2 groups compared with standard population and therefore, imply that GSTM1 genotype affects the severity of mustard lung. Altogether, present study findings were consistent with the results reported by Cheng et al.

31

According to their study GSTM1 deletion is a risk factor for developing the severe form of COPD while evaluated independently or in combination with other genes such as mEPHX.

In the case of GSTT1, there was not a remarkable association between gene deletion and the severity of mustard lung (adjusted OR, 0.676; 95% CI, 0.322-1.419). GSTT1 null genotype frequency in our studied population was in accordance with other studies in Iranian population.

30

The combinatorial communication of GSTT1 and GSTM1 with the severity of mustard lung was also examined. This analysis showed that a significant association was established between the genotypes and phenotypes. Although the P value was on the border of reliability, the simultaneous association of the disease with GSTM1 and GSTT1 was controversial. Accordingly, more studies may be required to determine this association with severity of mustard lung.

Genetic variations of GSTP1 are associated with COPD.

9

However, Associations between GSTP1 polymorphisms and the severity of pulmonary complications were doubtful in this study. Determined frequencies for GSTP1 polymorphisms in normal people were consistent with other studies in Iranian population.

32

One of the important functions of GSTM1 is to modulate inflammation-related signaling pathways.

17

When the expression of GSTM1 increases through ASK1 and c-Jun activation, this factor acts as a negative feedback. This function can protect cells from developing oxidative stress and inflammation. As shown, GSTM1 homozygous null genotype induces the more severe form of the mustard lung that indicates the importance of ASK1 pathway in the patients. In the other words, high values of GSTM1 deletion may lead to more activation of ASK1 and consequently, the generation of an inflammatory response. Further investigations are needed to determine the impact of the ASK1 pathway on the severity and molecular mechanism of the mustard lung.

Conclusion

In the present study, we have reported the potential association between genetic polymorphism of GSTM1 with the severity of the mustard lung because the GSTM1 null genotype was found frequently in sulfur mustard-exposed patients with severe and very severe stage of lung complications. Although mustard gas is the main cause of the disease initiation, the exploration of genetic polymorphism indicated a complex interplay of genes and environment in the mustard lung patients. The examination of ASK1 over-activation is required to provide more information about the molecular mechanisms of long-term complications of sulfur mustard.

Ethical approval

The study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki and on the basis of good clinical practice. All participants provided written informed consent in their native language.

33

Competing interests

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

This research was a combined effort of Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics of Tehran University and Immunoregulation Research Center of Shahed University. We would like to express our appreciation of all the individuals who participated in this investigation.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

simple

-

√ Sulfur mustard derivatives induce long-term complications

in respiratory system. Inflammatory response, oxidative

stress and airway obstruction are recognized as the main

symptoms of mustard lung.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ The severity of mustard lung is affected by GSTM1 gene

deletion, which proposes a complicated interplay among

genes after exposure to mustard gas.

References

- Ghabili K, Agutter PS, Ghanei M, Ansarin K, Shoja MM. Mustard gas toxicity: the acute and chronic pathological effects. J Appl Toxicol 2010; 30:627-43. doi: 10.1002/jat.1581 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghanei M, Amiri S, Akbari H, Kosari F, Khalili ARH, Alaeddini F. Correlation of sulfur mustard exposure and tobacco use with expression (immunoreactivity) of p53 protein in bronchial epithelium of Iranian “mustard lung” patients. Mil Med 2007; 172:70-4. doi: 10.7205/MILMED.172.1.70 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Khateri S, Ghanei M, Keshavarz S, Soroush M, Haines D. Incidence of lung, eye, and skin lesions as late complications in 34,000 Iranians with wartime exposure to mustard agent. J Occup Environ Med 2003; 45:1136-43. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000094993.20914.d1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Laskin JD, Black AT, Jan YH, Sinko PJ, Heindel ND, Sunil V. Oxidants and antioxidants in sulfur mustard-induced injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1203:92-100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05605.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tahmasbpour E, Reza Emami S, Ghanei M, Panahi Y. Role of oxidative stress in sulfur mustard-induced pulmonary injury and antioxidant protection. Inhal Toxicol 2015; 27:659-72. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2015.1092184 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Attaran D, Lari SM, Towhidi M, Marallu HG, Ayatollahi H, Khajehdaluee M. Interleukin-6 and airflow limitation in chemical warfare patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2010; 5:335-40. doi: 10.2147/copd.s12545 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghazanfari T, Yaraee R, Kariminia A, Ebtekar M, Faghihzadeh S, Vaez-Mahdavi MR. Alterations in the serum levels of chemokines 20 years after sulfur mustard exposure: Sardasht-Iran Cohort Study. Int Immunopharmacol 2009; 9:1471-6. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.08.022 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fryer AA, Bianco A, Hepple M, Jones PW, Strange RC, Spiteri MA. Polymorphism at the glutathione S-transferase GSTP1 locus A new marker for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161:1437-42. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9903006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Matsuse T, Teramoto S, Matsui H, Miyao M, Hosoi T. Glutathione S-transferase P1 (GSTP1) polymorphism in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999; 54:693-6. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.8.693 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mann CL, Davies MB, Boggild MD, Alldersea J, Fryer AA, Jones PW. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms in MS: their relationship to disability. Neurology 2000; 54:552-7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.54.3.552 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mattey DL, Hassell AB, Plant M, Dawes PT, Ollier WR, Jones PW. Association of polymorphism in glutathione S-transferase loci with susceptibility and outcome in rheumatoid arthritis: comparison with the shared epitope. Ann Rheum Dis 1999; 58:164-8. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.3.164 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Shan Z, Luo C, Kang C, Yang Y, He P. Glutathione S-Transferase T1 (GSTT1) Null Polymorphism, Smoking, and Their Interaction in Coronary Heart Disease: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Heart Lung Circ 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.07.005 [Crossref]

- Tang J, Zhou Q, Zhao F, Wei F, Bai J, Xie Y. Association of glutathione S-transferase T1, M1 and P1 polymorphisms in the breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis in Asian population. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8:12430. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S104339 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zendehdel K, Bahmanyar S, McCarthy S, Nyren O, Andersson B. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase genes GSTP1, GSTM1, and GSTT1 and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia cancers. Cancer Causes Control 2009; 10:2031-8. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9399-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Caccuri AM, Antonini G, Board PG, Flanagan J, Parker MW, Paolesse R. Human glutathione transferase T2-2 discloses some evolutionary strategies for optimization of substrate binding to the active site of glutathione transferases. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:5427-31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002819200 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Berhane K, Widersten M, Engstrom A, Kozarich JW, Mannervik B. Detoxication of base propenals and other alpha, beta-unsaturated aldehyde products of radical reactions and lipid peroxidation by human glutathione transferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91:1480-4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1480 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cho SG, Lee YH, Park HS, Ryoo K, Kang KW, Park J. Glutathione S-transferase mu modulates the stress-activated signals by suppressing apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:12749-55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005561200 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Soga M, Matsuzawa A, Ichijo H. Oxidative Stress-Induced Diseases via the ASK1 Signaling Pathway. Int J Cell Biol 2012; 2012:439587. doi: 10.1155/2012/439587 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187:347-65. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Dykes D, Polesky H. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1988; 16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Rahman SZ, El-Zein RA, Anwar WA, Au WW. A multiplex PCR procedure for polymorphic analysis of GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes in population studies. Cancer Lett 1996; 107:229-33. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(96)04832-X [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Harries LW, Stubbins MJ, Forman D, Howard G, Wolf CR. Identification of genetic polymorphisms at the glutathione S-transferase Pi locus and association with susceptibility to bladder, testicular and prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis 1997; 18:641-4. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.4.641 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sprenger R, Schlagenhaufer R, Kerb R, Bruhn C, Brockmöller J, Roots I. Characterization of the glutathione S-transferase GSTT1 deletion: discrimination of all genotypes by polymerase chain reaction indicates a trimodular genotype–phenotype correlation. Pharmacogenetics 2000; 10:557-65. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200008000-00009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xu S-j, Wang Y-p, Roe B, Pearson WR. Characterization of the Human Class Mu GlutathioneS-Transferase Gene Cluster and the GSTM1Deletion. J Biol Chem 1998; 273:3517-27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3517 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hansa J, Ghosh SK, Agrawala SK, Kashyap MP. Risk and Frequency of Mutations in the BRCA1 in Relation to GSTM1 and GSTT1 Genotypes in Breast Cancer. Adv Biores 2015; 6:86-89. doi: 10.15515/abr.09764585.6.1.8689 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kumar O, Sugendran K, Vijayaraghavan R. Protective effect of various antioxidants on the toxicity of sulphur mustard administered to mice by inhalation or percutaneous routes. Chem Biol Interact 2001; 134:1-12. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(00)00209-X [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shohrati M, Ghanei M, Shamspour N, Babaei F, Abadi MN, Jafari M. Glutathione and malondialdehyde levels in late pulmonary complications of sulfur mustard intoxication. Lung 2010; 188:77-83. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9178-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zimniak P, Nanduri B, Pikuła S, Bandorowicz‐Pikuła J, Singhal SS, Srivastava SK. Naturally occurring human glutathione S‐transferase GSTP1‐1 isoforms with isoleucine and valine in position 104 differ in enzymic properties. Eur J Biochem 1994; 224:893-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00893.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ji X, Blaszczyk J, Xiao B, O'Donnell R, Hu X, Herzog C. Structure and Function of Residue 104 and Water Molecules in the Xenobiotic Substrate-Binding Site in Human Glutathione S-Transferase P1-1. Biochemistry 1999; 38:10231-8. doi: 10.1021/bi990668u [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rafiee L, Saadat I, Saadat M. Glutathione S-transferase genetic polymorphisms (GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTO2) in three Iranian populations. Mol Biol Rep 2010; 37:155-8. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9565-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cheng SL, Yu CJ, Chen CJ, Yang PC. Genetic polymorphism of epoxide hydrolase and glutathione S-transferase in COPD. Eur Respir J 2004; 23:818-24. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00104904 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad SH. Glutathione S-transferase gene polymorphisms (GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1) and prostate cancer: a case-control study in Tehran, Iran. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2011; 14:105-13. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.54 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Association WM. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013; 310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]