BioImpacts. 9(3):189-193.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2019.23

Short Communication

Manifestation of hemispheric laterality in chewing side preference and handedness

Saeed Khamnei 1, Seyyed-Reza Sadat-Ebrahimi 2, 3, Shaker Salarilak 4, Siavash Savadi Oskoee 5, Yousef Houshyar 6, Seyed Kazem Shakouri 6, Yaghoub Salekzamani 6, Masumeh Zamanlu 7, *

Author information:

1 Department of Physiology, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran

2 Neurosciences Research Center (NSRC), Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3 Student Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4 Public Health Department, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran

5 Dental and Periodontal Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

6 Research Center of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

7 Self-awareness Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

Humans manifest a behavioral inclination towards more utility of one side of the body, in relation with the dominant hemisphere of the brain. The current investigation assessed handedness together with chewing preference which have not been evaluated in various food textures before.

Methods:

Nineteen young and healthy volunteers chewed hard (walnut) and soft (cake) foods, during surface electromyography recording from masseter muscles. The side of the first and all chews in the two food types were determined and compared with the side of the dominant hand.

Results:

Results indicated the two lateralities in the same side considerably (60%-70%), implying the solidarity in the control of the dominant hemisphere of the brain. The unilaterality was more prominent in the assessment of all chews in hard food, with higher statistical agreement and correlation.

Conclusion:

Thereupon masticatory preference is found with probable origins in the dominant hemisphere of the brain.

Keywords: Masticatory preference, Hemispheric dominancy, Food texture, Hand-chew preference, Chewing laterality

Copyright and License Information

© 2019 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

The definition about laterality for the related researches has been propounded as “behavioral manifestations of the cerebral dominance in which there is a preferential use and superior functioning of either the left or the right side, as in the preferred use of right hand or right foot” (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2007). During decades, different kinds of lateralities, including handedness, footedness, eyedness, and earedness have been investigated which could guide towards recognizing the procedures of cerebral controlling.

1-5

Moreover, there are some disorders related to the laterality, sometimes in need of interference.

6,7

Chewing side preference, a type of laterality, has been introduced and discussed mainly in dentistry literature;

8-12

and a few authors have investigated the cerebral aspects of this laterality. This motif is under research worldwide, and there are inconsistencies in the methods and results, relating the chewing laterality to the developmental aspects, as well as age,

13-16

or dental parameters such as complete denture-wearing, occlusal contact, articular especially temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction, and so on; whether such associations being demonstrated or refused.

12,17-25

Pain was also assessed, however no relation with chewing side preference was seen.

26

There are reports about the masticatory laterality and other lateralities (e.g., handedness, footedness), bringing about controversial results. Martinez-Gomis et al concluded that masticatory preference in dentate subjects is related to bite force and occlusal contact area but not to handedness.

18

But Nissan et al claimed that “chewing side preference correlated with other tested hemispherical literalities”.

22

A classic study in 1987 also claimed chewing preference is correlated with other lateral preferences.

27

Serel Arslan et al reported similar results in 2017.

28

Another study in 2012 reported that various lateralities do not show any strong correlation with chewing side preference.

25

Overall, challengingly, it is still unanswered whether or not chewing and handedness are similar?

29

The current investigation studied this question from novel points, using EMG recording as a more objective and determining tool, assessing first chews and all chews by a hard food and a soft food in order to implement a comprehensive and efficient method for evaluating chewing side preference; then analyzing its relation with handedness as the outstanding manifestation of the dominant hemisphere.

Materials and Methods

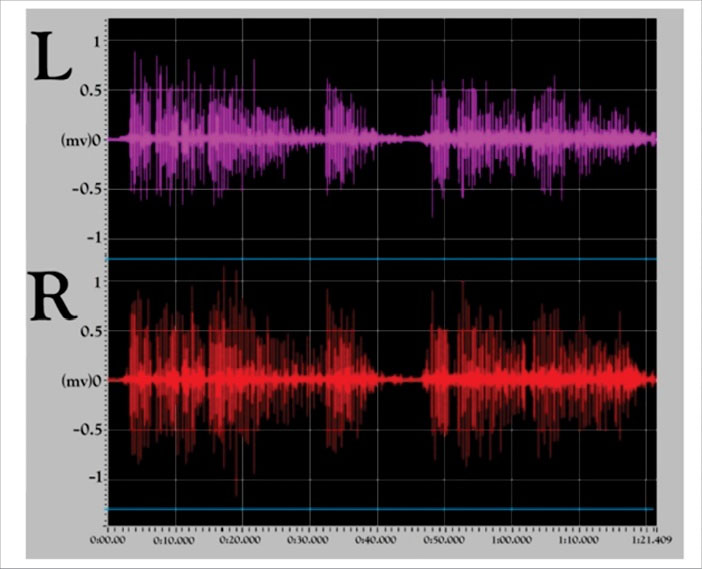

Nineteen young and healthy volunteers were recruited. They chewed hard (walnut) and soft (cake) foods, and surface electromyography was recorded from their masseter muscles. An example EMG recording is shown in Fig. 1. The side of the first and all chews in the two food types were determined and compared with the side of the dominant hand by analyses for correlations and agreements. Details of the methods are presented in the supplementary.

Figure 1.

Surface electromyography recording of masseter muscles of a male volunteer during mastication, L: the left side, R: the right side. As can be seen, the right waves are more dominant and the subject is chewing by the right side.

.

Surface electromyography recording of masseter muscles of a male volunteer during mastication, L: the left side, R: the right side. As can be seen, the right waves are more dominant and the subject is chewing by the right side.

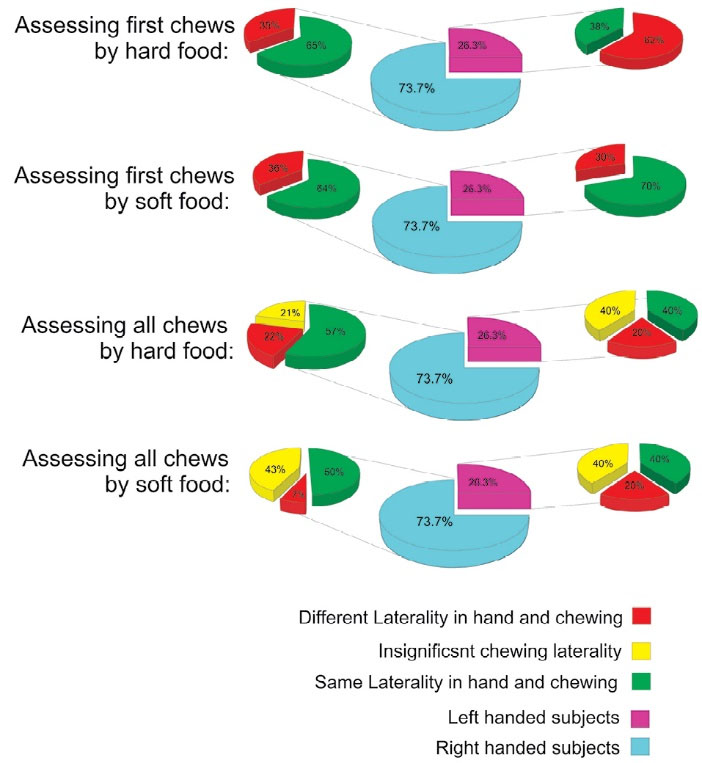

From the 19 participants, 73.7% (n=14) were right handed and 26.3% (n=5) were left handed (Fig. 2). The investigators of the current study tried to include more left handed subjects to the study to facilitate the analyses.

Fig. 2.

Percent of handedness in subjects (more left handed subjects were recruited intentionally in order to facilitate analyses) and percent of concordance of lateralities in each group.

.

Percent of handedness in subjects (more left handed subjects were recruited intentionally in order to facilitate analyses) and percent of concordance of lateralities in each group.

In order to assess the similarity of chewing of left handed participants and right handed participants, as well as the similarity of the experiments, the distribution of chewing velocity, number of chews, and time of mastication was assessed in both right handed and left handed subjects.

Results and Discussion

Results showed no statistical differences between the two groups (P > 0.1, Table 1). Results also showed no correlation of the side of handedness with gender and age (P = 0.21, 0.64, respectively).

Table 1.

Handedness versus age, gender, chewing velocity, number of chews, time of mastication

|

Handedness

|

Number of subjects (%)

|

Gender: Number (% of all)

|

Age mean ± SD

|

Food type

|

Chewing velocity

|

Number of chews

|

Time of mastication

|

|

Male

|

Female

|

| Right handed |

14 (73.7) |

4 (21.1) |

10 (52.6) |

19.57 ± 2.17 |

Hard |

1.50 (0.47) |

35.0 ± 6.5 |

26.56 ± 15.23 |

| Soft |

1.24 (0.40) |

70.2 ± 14.7 |

61.12 ± 19.27 |

| Left handed |

5 (26.3) |

3 (15.8) |

2 (10.5) |

19.00 ± 2.74 |

Hard |

1.64 (0.58) |

33.4 ± 8.8 |

21.08 ± 3.80 |

| Soft |

1.38 (0.58) |

62.0 ± 14.1 |

51.39 ± 19.82 |

| Difference P value |

- |

0.211 |

0.642 |

Hard |

0.607 |

0.671 |

0.444 |

| Soft |

0.572 |

0.293 |

0.349 |

The rate of similar sides in the two lateralities was more than 50% in all four occurrences that we determined for masticatory preference in the two groups of left and right handed subjects except once. When strong masticatory preference was considered, this similarity was 40% or more. However results showed no significant correlation between the four occurrences and handedness (P > 0.05), while agreements between them were average and low. Rates of concordance of lateralities in right handed subjects and left handed subjects are shown in Table 2 with regard to general masticatory preference and in Fig. 2 with regard to strong masticatory preference. The P values of the correlations and the levels of agreements are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Percent of similarity, agreement, and correlation of handedness and masticatory preference

|

The assessed chews

|

Food type

|

Concordance of masticatory preference with handedness (%)

|

Kappa agreement of masticatory preference with handedness

|

P

value of chi-square correlation

|

| First |

Hard |

58 |

Average |

0.710 |

| First |

Soft |

63.2 |

Low |

0.255 |

| All |

Hard |

68.5 |

Average |

0.089

|

| All |

Soft |

68.5 |

Low |

0.764 |

The results of this study indicated that more than half of the individuals have the two lateralities of chewing side preference and handedness in the same side. When the laterality was assessed by all chewing cycles, the obtained unilaterality was about 70%. Therefore it can be concluded, regarding these results, that few of our subjects have these two lateralities cross-sided. The reason for such unilaterality may be explained by the interference of the handedness: because the food is carried with the dominant hand, thus primary chews are done in the same dominant side. But as we see the unilaterality is more considerable in assessing all chews not in primary chews, and there should be independent pathways or mechanisms for chewing preference, much more than such simple interferences.

As reported by other authors, most of the individuals preferred to chew by the right side,

16,18,30

and we previously reported highly significant masticatory preference towards the right side (P<0.001). Furthermore, nearly one third of the subjects had all four occurrences of chewing preference on the right side and no one had four occurrences on the left.

31

We should also consider that more than 90% of the people have their right hand as dominant, with a little lower percentage of right dominancy in other lateralities such as footedness, eyedness, and so forth.

3,32-39

, Moreover, medical physiology text claims that almost 95% of individuals show the left angular gyrus and temporal lobe as dominant. Furthermore, "the motor areas for controlling hands are also dominant in the left side of the brain in about 9 out of 10 persons, thus causing right-handedness in most people".

40

Therefore, it seems that the laterality and dominance as well as the masticatory preference tend to be on the left brain hemisphere and the contralateral right side of the body, and this brings about the role of brain in determining chewing side preference, although it is difficult to be proved completely.

Unilaterality may represent the attempt of the brain to direct all lateralities to the same side, the side under the control of the dominant hemisphere. An important consequence of unilaterality is facilitation of the ordinary daily activities, for example eating. Similarly, the aim of hemispheric dominancy has been explained as “direction of mind's attention to the better developed regions for learning, resulting in the increase of rate of learning in the cerebral hemisphere that gains the first start”.

40

Fig. 2 shows that this unilaterality is more prominent in right handed subjects, and a considerable percent of left handed subjects have their chewing preference on the right side. It should be reminded that left side of the brain is dominant for many left handed subjects as well. Actually, in order to discuss the role of dominant hemisphere precisely in this regard, an investigation should recruit numerous left handed subjects with their dominant hemisphere on the right side (proved by functional magnetic resonance imaging- fMRI- or advanced methods), which are scarce, as much as less than 5% of the population.

Unilaterality of different dimensions is called unilateral cerebral dominancy, but in 20% of people there is mixed or cross dominancy/laterality, meaning that at least two lateralities are on the opposite side (usually hand opposite foot or eye).

41

Cross dominancy may have some advantages in activities such as playing baseball,

42

but it has been reported to have relations with physical, mental, or emotional dysfunctions or schizophrenic personalities.

6,41

Cross dominancy could be considered an abnormality which would be relieved by some interventions.

41

Food texture has been demonstrated to influence masticatory pattern, and this may be a cortical event as well, reducing or increasing the mentioned interaction of hand-chew preference. If so, based upon the results of the current study, hard texture increases this interaction. This brings about the interesting subject of brain areas involved in food texture perception and the resultant effects. Perception of food texture include sensory modalities (e.g., vision, taste) and psychological matters

43,44

which surely pass cortical areas, thereupon, food texture could remarkably be associated with brain cortex. Takahashi et al studied the areas of cortex which are involved in perception of hardness of food, claiming selective activations of multiple cortical areas of the right and left hemispheres, as hardness of a gum changed during mastication.

45

It can thus be postulated that the cross relation of hand-chew preference and food texture is probably located in cortex. It should be mentioned that all P values of correlation among the four occurrences of chewing preference and handedness were insignificant, while in the experiment of all chews with the hard food it showed marginal significance.

Chewing frequently with the same side can wear the teeth, masticatory muscles, and tempro-mandibular joint of that side. Therefore, determining the preferred chewing side in dentistry could be beneficent in preparation of dental prosthetics or dentures or in regard to the dental examinations.

22,30

For determining the preferred chewing side as a basic dentistry examination and history, dentists initially can question the dominant hand side, together with observing the side of the first chew, which we have suggested earlier;

31

and if they were inconsistent, the latter would be more valid, as a matter of statistical conclusions.

Conclusion

We conclude that masticatory preference could be considered similar to hand laterality, with probable origins in the dominant hemisphere of the brain.

Acknowledgment

We wish to express our gratitude to the subjects for voluntarily participating in the experiments. We also wish to appreciate Dr Yaser Hadidi’s kind help in language editing of this manuscript and Dr Gisu Mohaddess for the literature search.

The abstract of this investigation was presented and published in the “21st International Iranian Congress of Physiology and Pharmacology, Aug 2013 Tabriz, Iran”.

Funding sources

The current investigation was financially supported by the Research Center of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Ethical statement

Subjects were incorporated after obtaining written informed consent. The standards of this study were approved by the Research Vice-Chancellor of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and the Ethics Committee of the University.

Conflict of interests

None.

Authors' contribution

SK proposed the subject and general design of the research and supervised the entire research. MZ presented the literature review and precise design of the research. SSO cooperated for dental examination of subjects and dentistry aspects of the research. MZ, SKS, YH, and YS performed the EMG recordings and the three latter performed the analysis for EMG waves to produce raw data. SS and MZ analyzed the raw data. SRSE handled the data and cooperated for data preparation and presentation and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and revised and approved the manuscript.

Report Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

simple

-

√ Laterality is a behavioral inclination towards more utility of one side of the body, probably in relation with hemispheric dominancy.

-

√ Laterality in chewing is named masticatory preference and most of the individuals prefer to chew by the right side.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ More than half of the individuals have the two lateralities of chewing side preference and handedness in the same side.

-

√ When the laterality was assessed by all chewing cycles of the hard food, this obtained unilaterality was about 70%.

-

√ Masticatory preference, similar to hand laterality, possesses probable origins in the dominant hemisphere of the brain.

References

- Dittmar M. Functional and postural lateral preferences in humans: interrelations and life-span age differences. Hum Biol 2002; 74:569-85. doi: 10.1353/hub.2002.0040 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mohr C, Bracha HS. Compound measure of hand-foot-eye preference masked opposite turning behavior in healthy right-handers and non-right-handers: technical comment on Mohr et al (2003). Behav Neurosci 2004; 118:1145-6. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.5.1145 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Reiss M. Genetic associations between lateral signs. Anthropol Anz 1999; 57:61-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Reiss M, Reiss G. [Medical problems of handedness]. Wien Med Wochenschr 2002; 152:148-52. [ Google Scholar]

- Strauss E, Wada J. Lateral preferences and cerebral speech dominance. Cortex 1983; 19:165-77. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(83)80012-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nicholls ME, Orr CA, Lindell AK. Magical ideation and its relation to lateral preference. Laterality 2005; 10:503-15. doi: 10.1080/13576500442000265 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Rabkin R, Kramer Y. The relationship between mixed dominance and reading disabilities. J Pediatr 1959; 54:76-80. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(59)80040-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Christensen LV, Radue JT. Lateral preference in mastication: a feasibility study. J Oral Rehabil 1985; 12:421-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1985.tb01547.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Christensen LV, Radue JT. Lateral preference in mastication: an electromyographic study. J Oral Rehabil 1985; 12:429-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1985.tb01548.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Devlin H, Wastell DG, Duxbury AJ, Grant AA. Chewing side preference and muscle quality in complete denture-wearing subjects. J Dent 1987; 15:23-5. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(87)90092-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Garcia RI, Perlmuter LC, Chauncey HH. Effects of dentition status and personality on masticatory performance and food acceptability. Dysphagia 1989; 4:121-6. doi: 10.1007/BF02407157 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wilding RJ, Adams LP, Lewin A. Absence of association between a preferred chewing side and its area of functional occlusal contact in the human dentition. Arch Oral Biol 1992; 37:423-8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(92)90027-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gisel EG. Chewing cycles in 2- to 8-year-old normal children: a developmental profile. Am J Occup Ther 1988; 42:40-6. doi: 10.5014/ajot.42.1.40 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gisel EG. Development of oral side preference during chewing and its relation to hand preference in normal 2- to 8-year-old children. Am J Occup Ther 1988; 42:378-83. doi: 10.5014/ajot.42.6.378 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Leconte P, Fagard J. Lateral preferences in children with intellectual deficiency of idiopathic origin. Dev Psychobiol 2006; 48:492-500. doi: 10.1002/dev.20167 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mc Donnell ST, Hector MP, Hannigan A. Chewing side preferences in children. J Oral Rehabil 2004; 31:855-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01316.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pond LH, Barghi N, Barnwell GM. Occlusion and chewing side preference. J Prosthet Dent 1986; 55:498-500. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(86)90186-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gomis J, Lujan-Climent M, Palau S, Bizar J, Salsench J, Peraire M. Relationship between chewing side preference and handedness and lateral asymmetry of peripheral factors. Arch Oral Biol 2009; 54:101-7. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.09.006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Devlin H, Wastell D, Duxbury A, Grant A. Chewing side preference and muscle quality in complete denture-wearing subjects. J Dent 1987; 15:23-5. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(87)90092-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kirveskari P, Alanen P. Right-left asymmetry of maximum jaw opening. Acta Odontol Scand 1989; 47:101-3. [ Google Scholar]

- Nissan J, Berman O, Gross O, Haim B, Chaushu G. The influence of partial implant‐supported restorations on chewing side preference. J Oral Rehabil 2011; 38:165-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02142.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nissan J, Gross MD, Shifman A, Tzadok L, Assif D. Chewing side preference as a type of hemispheric laterality. J Oral Rehabil 2004; 31:412-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01256.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wilding RJ, Lewin A. A model for optimum functional human jaw movements based on values associated with preferred chewing patterns. Arch Oral Biol 1991; 36:519-23. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(91)90145-K [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hoogmartens MJ, Caubergh MA, De Geest M. Occlusal, articular and temporomandibular joint dysfunction parameters versus chewing preference during the first chewing cycle. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1987; 27:7-11. [ Google Scholar]

- Barcellos DC, da Silva MA, Batista GR, Pleffken PR, Pucci CR, Borges AB. Absence or weak correlation between chewing side preference and lateralities in primary, mixed and permanent dentition. Arch Oral Biol 2012; 57:1086-92. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.02.022 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Christensen LV, Radue JT. Lateral preference in mastication: relation to pain. J Oral Rehabil 1985; 12:461-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1985.tb01292.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hoogmartens MJ, Caubergh MA. Chewing side preference in man correlated with handedness, footedness, eyedness and earedness. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1987; 27:293-300. [ Google Scholar]

- Serel Arslan S, Inal O, Demir N, Olmez MS, Karaduman AA. Chewing side preference is associated with hemispheric laterality in healthy adults. Somatosens Mot Res 2017; 34:92-5. doi: 10.1080/08990220.2017.1308923 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Exchange BS. Do the right-handed people tend to use the right side teeth of their jaw to chew food more often than the left-handed people? [website] Biology Stack Exchange: Biology Stack Exchange; 2014 [updated 2015-01-07; cited 2016 2016-9-2]; Available from: http://biology.stackexchange.com/questions/24631/do-the-right-handed-people-tend-to-use-the-right-side-teeth-of-their-jaw-to-chew.

- Varela JM, Castro NB, Biedma BM, Da Silva Dominguez JL, Quintanilla JS, Munoz FM. A comparison of the methods used to determine chewing preference. J Oral Rehabil 2003; 30:990-4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01085.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zamanlu M, Khamnei S, Salarilak S, Oskoee SS, Shakouri SK, Houshyar Y. Chewing side preference in first and all mastication cycles for hard and soft morsels. Int J Clin Exp Med 2012; 5:326-31. [ Google Scholar]

- Annett M. Left-handedness as a function of sex, maternal versus paternal inheritance, and report bias. Behav Genet 1999; 29:103-14. [ Google Scholar]

- Barut C, Ozer CM, Sevinc O, Gumus M, Yunten Z. Relationships between hand and foot preferences. Int J Neurosci 2007; 117:177-85. doi: 10.1080/00207450600582033 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ocklenburg S, Burger C, Westermann C, Schneider D, Biedermann H, Gunturkun O. Visual experience affects handedness. Behav Brain Res 2010; 207:447-51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.10.036 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Reiss M, Reiss G. Lateral preferences in a German population. Percept Mot Skills 1997; 85:569-74. doi: 10.2466/PMS.85.6.569-574 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Reiss M, Reiss G. [Current aspects of handedness]. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1999; 111:1009-18. [ Google Scholar]

- Reiss M, Reiss G. Earedness and handedness: distribution in a German sample with some family data. Cortex 1999; 35:403-12. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70808-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Schott GD, Schott JM. Mirror writing, left-handedness, and leftward scripts. Arch Neurol 2004; 61:1849-51. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.12.1849 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bryden M. Handedness, cerebral lateralization, and measures of “latent left-handedness”. Int J Neurosci 1989; 44:227-33. doi: 10.3109/00207458908986203 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Hall JEGAC. Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology. Philadelphia, PA.: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

-

Anonymous. Laterality. http://pages.prodigy.net/unohu/dominance.htm. Accessed May 2010.

- Portal JM, Romano PE. Major review: ocular sighting dominance: a review and a study of athletic proficiency and eye-hand dominance in a collegiate baseball team. Binocul Vis Strabismus Q 1998; 13:125-32. [ Google Scholar]

- Mathoniere C, Mioche L, Dransfield E, Culioli J. Meat texture characterisation: comparison of chewing patterns, sensory and mechanical measures. J Texture Stud 2000; 31:183-203. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2000.tb01416.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Szczesniak AS. Texture is a sensory property. Food Qual Prefer 2002; 13:215-25. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(01)00039-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Miyamoto T, Terao A, Yokoyama A. Cerebral activation related to the control of mastication during changes in food hardness. Neuroscience 2007; 145:791-4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.044 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]