Bioimpacts. 9(2):89-95.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2019.12

Original Research

Chondroitin sulfate degradation and eicosanoid metabolism pathways are impaired in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: Experimental confirmation of an in silico prediction

Shiva Kalantari 1, Mohammad Naji 2, Mohsen Nafar 2, *  , Hootan Yazdani-Kachooei 3, Nasrin Borumandnia 2, Mahmoud Parvin 4

, Hootan Yazdani-Kachooei 3, Nasrin Borumandnia 2, Mahmoud Parvin 4

Author information:

1Chronic Kidney Disease Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2Urology-Nephrology Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Department of Biology, Faculty of Basic Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch, Tehran, Iran

4Department of Pathology, Shahid Labbafinejad Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), the most common primary glomerular disease, is a diverse clinical entity that occurs after podocyte injury. Although numerous studies have suggested molecular pathways responsible for the development of FSGS, many still remain unknown about its pathogenic mechanisms. Two important pathways were predicted as candidates for the pathogenesis of FSGS in our previous in silico analysis, whom we aim to confirm experimentally in the present study.

Methods:

The expression levels of 4 enzyme genes that are representative of "chondroitin sulfate degradation" and "eicosanoid metabolism" pathways were investigated in the urinary sediments of biopsy-proven FSGS patients and healthy subjects using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). These target genes were arylsulfatase, hexosaminidase, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and prostaglandin I2 synthase. The patients were sub-divided into 2 groups based on the range of proteinuria and glomerular filtration rate and were compared for variation in the expression of target genes. Correlation of target genes with clinical and pathological characteristics of the disease was calculated and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed.

Results:

A combined panel of arylsulfatase, hexosaminidase, and COX-2 improved the diagnosis of FSGS by 76%. Hexosaminidase was correlated with the level of proteinuria, while COX-2 was correlated with interstitial inflammation and serum creatinine level in the disease group.

Conclusion:

Our data supported the implication of these target genes and pathways in the pathogenesis of FSGS. In addition, these genes can be considered as non-invasive biomarkers for FSGS.

Keywords: Biomarker, Chondroitin sulfate, Eicosanoid metabolism, Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, Molecular pathway

Copyright and License Information

© 2019 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a progressive glomerular disease with scarring that occurs secondary to podocyte injury.

1,2

Loss, damage, and detachment of podocytes induced by a series of causes result in the obstruction of capillary lumina by the matrix in part (segmental) of the glomerular capillaries in a portion (focal) of glomeruli.

1,3

The podocyte injury might be the consequence of several insults such as hyperglycemia and insulin signaling, circulating permeability factors, genetic factors, mechanical stretch, angiotensin II, calcium signaling, viral infection, chronic pyelonephritis, toxins, drug use, and immunological injury,

4-7

or other unknown mechanisms. These insults might either induce primary (approximately 80% of cases) or secondary FSGS (remaining 20%). The widely studied cause of the primary form of FSGS is circulating permeability factors that are mostly composed of soluble urokinase plasminogen-activator receptor (suPAR),

8

cardiotrophin-like cytokine-1 (CLC-1),

5

and angiopoietin-like-4 (Angptl4).

9

The genes whose mutation may induce FSGS are related to slit diaphragm, actin cytoskeleton or foot process-GBM interaction.

7

These susceptible genes include NPHS1,

10

NPHS2,

11

PLCE1,

12

WT1,

13

LAMB2,

14

PTPRO,

15

ARHGDIA,

16

ADCK4,

17

TRPC6,

18

and APOL1.

19

This podocytopathy mostly presents with proteinuria and some characteristics of nephrotic syndrome including hypoalbuminemia, hypercholesterolemia, and peripheral edema.

20

The diagnostic gold standard for FSGS is histopathologic features in kidney biopsy, which elucidate the segmental glomerular scares, tubular changes, and hypertrophy in light microscopy and podocyte microvillous transformation, foot process effacement, and tubuloreticular inclusions in electron microscopy.

21

Ever since the first presentation of FSGS by Arnold Rich in 1959,

22

many studies have been conducted to identify the impaired biological processes, molecular pathways, and non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for FSGS.

23-26

Nevertheless, the pathogenic pathways of FSGS especially in the primary form are still under investigation.

An in silico study of FSGS by our research group revealed the involvement of several pathways in the pathogenesis of FSGS including “chondroitin sulfate degradation” and “eicosanoid metabolism”.

23

Based on this result, we designed an experiment for confirming the hypothesis of impairment of these 2 important pathways in the development of FSGS. Four important enzymes involved in these pathways were targeted for investigation: arylsulfatase and N-acetylglucosaminidase (also known as hexosaminidase) for chondroitin sulfate degradation pathway, and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and prostaglandin I2 synthase for eicosanoid metabolism pathway. The potential diagnostic role of the target genes was also examined.

Methods

Sample collection and preparation

Urine samples were collected from 20 biopsy-proven FSGS patients and 17 healthy volunteers, and urine sediment was acquired by centrifugation at 14 000 g at 4°C for 8 minutes. All the samples were stored at -80°C until use. The disease of patients was diagnosed as primary glomerulonephritis and subjects with secondary diseases and other complications such as diabetes and malignancies were excluded. The healthy volunteers were confirmed based on common laboratory tests.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription

RNA isolation from urine sediment samples was performed using RNX-Plus (Cinnagen, Tehran, Iran) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality was determined through purity and concentration measurements using WPA spectrophotometer (Biochrom) and genomic DNA contamination was removed using DNase I (RNase-free) (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Total RNA extracted from urine sediment samples was reverse transcribed using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Based on the protocol provided by the manufacturer, the mixture of the random hexamer, oligo (dT) primers and other appropriate reagents were prepared in the final volume of 20 μL. Synthesis of cDNA was performed with 0.3 μg of the isolated mRNA as a template at 42°C for 60 minutes, 25°C for 5 minutes, and 42°C for 60 minutes. The reaction was then terminated at 70°C for 5 minutes. The cDNA was stored at −80°C.

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

All primers were designed using AlleleID 6 software (see Supplementary file 1, Table S1) and synthesized by Macrogen (Macrogen, South Korea). A 20 µL of the mixture of the following components was used for mRNA quantification: 10 μL RealQ Plus 2X Master Mix Green (Ampliqon, Denmark), 1 μL first-strand cDNA template, 0.8 μL of each primer of target genes (arylsulfatase, hexosaminidase, COX-2, prostaglandin I2 synthase), and distilled water. Parameters of thermocycling were 15 minutes at 95°C for enzyme activation followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 20 seconds and termination at 60°C for 60 seconds using Rotor-Gene Q instrument (Qiagen). Expression levels of mRNAs were normalized against the expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Relative expression of genes was calculated using 2−∆Ct method.

Statistical analysis

Non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare different variables (relative expression of target genes) between the patient and control groups and between the subgroups of patients based on the range of proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Correlation between target genes and clinical and pathological characteristics in the patient group was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation. These clinical and pathological features were eGFR, serum creatinine, proteinuria, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA), interstitial inflammation, glomerular sclerosis, and mesangial hypercellularity. To assess and compare the diagnostic role of target genes in the study groups, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed and the areas under the curves (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity were calculated. Combination of target genes as a diagnostic panel for ROC analysis was carried out using multiple logistic regression. Linear regression analysis was also performed to compare the ability of target genes in the prediction of eGFR and proteinuria. All data were presented as median and range. P value < 0.05 was considered significant. R program version 3.4.3.3 was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

Patients and controls

Patients were included in this study after pathologic diagnosis by kidney biopsy. The patients were subdivided into 2 groups based on the level of proteinuria and renal function status (i.e. eGFR). Accordingly, 12 patients had nephrotic-range proteinuria (>3 g/d), eight patients had sub-nephrotic-range proteinuria (< 3 g/d), 12 patients had eGFR < 60 (m/min/1.73 m2), and eight patients had eGFR > 60 (m/min/1.73 m2). Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical information of patients and healthy subjects. The patients and healthy groups were adjusted based on sex and age to reduce their confounding effects.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of patients and healthy individuals

|

|

Patients (n=20)

|

Healthy (n=17)

|

| Age (y) |

48 (23-82) |

49 (25-55) |

| Men |

12 (40%) |

8 (47%) |

| BUN (mg/dL) |

21.49 (9.34-45.32) |

21 (8.9-23) |

| SCr (mg/dL) |

1.31 (0.7-3.09) |

0.9 (0.7-1.2) |

| Chol (mg/dL) |

200.5 (192-292) |

178 (85-192) |

| TG (mg/dL) |

179 (72-363) |

138 (75-149) |

| HDL (mg/dL) |

46 (36-64) |

73 (39-86) |

| LDL (mg/dL) |

112 (53-183) |

121 (73-129) |

| FBS |

103 (70-110) |

93 (80-108) |

| Proteinuria (mg/24h) |

1785 (700-19695) |

- |

|

eGFR (m/min/1.73 m2)

|

50 (20-115) |

85 (51-102) |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; SCr, serum creatinine; Chol, cholesterol; TG, Triglyceride; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBS, fast blood sugar.

Note: Data are presented as median (range). Percentage of men in each pathologic group is presented in parenthesis.

Evaluation of gene expression changes between patients and healthy individuals

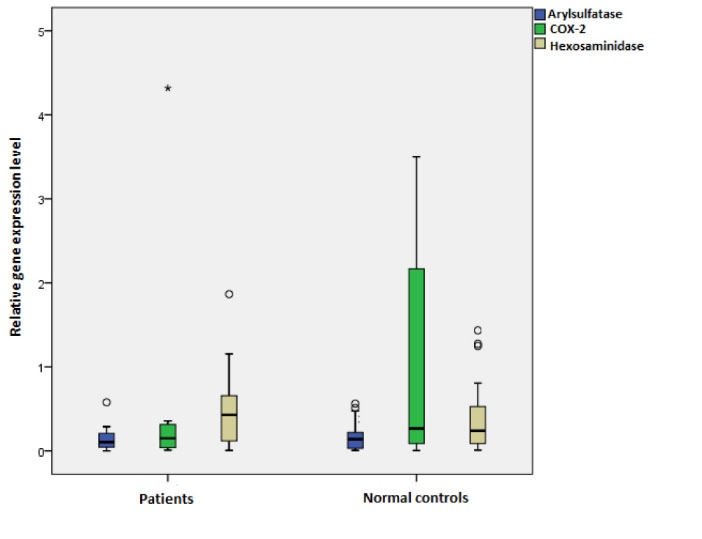

The comparison of every single gene between patients and healthy subjects was not significant (Table 2), and the AUC was poor, however, the ROC analysis for the combination of three target genes (hexosaminidase, arylsulphatase, COX-2) improved the diagnosis of patients group to 76% (Fig. S1). The expression level of prostaglandin I2 synthase was lower than the limit of detection in real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in the urine sediment and therefore its comparison with other genes in diagnosis was not possible. The panel of these three genes could diagnose the patients from healthy individuals with a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 67%. The details of the diagnostic evaluation of each gene separately and in combination are shown in Table 2. The descriptive comparison of the expression level of these genes between patients and healthy subjects is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Relative expression level of target genes in FSGS patients compared to healthy individuals. No significant changes were observed between patients and control subjects in relative expression of the genes. (Arylsulphatase P-value = 0.947, Hexosaminidase P-value = 0.604, COX-2 P-value = 0.330). The star (*) shows the existence of outlier in COX-2 of patients group.

.

Relative expression level of target genes in FSGS patients compared to healthy individuals. No significant changes were observed between patients and control subjects in relative expression of the genes. (Arylsulphatase P-value = 0.947, Hexosaminidase P-value = 0.604, COX-2 P-value = 0.330). The star (*) shows the existence of outlier in COX-2 of patients group.

Table 2.

The ROC analysis results for the diagnosis of FSGS patients from control subjects based on each target gene alone and in combination

|

Gene

|

Specificity

|

Sensitivity

|

AUC

|

| Arylsulfatase |

53% |

62% |

0.57 |

| Hexosaminidase |

95% |

24% |

0.55 |

| COX-2 |

87% |

42% |

0.6 |

| Arylsulfatase + Hexosaminidase |

42% |

87% |

0.65 |

| Arylsulfatase + Hexosaminidase + COX-2 |

67% |

82% |

0.76 |

Evaluation of target genes and their effects on disease progression in patients

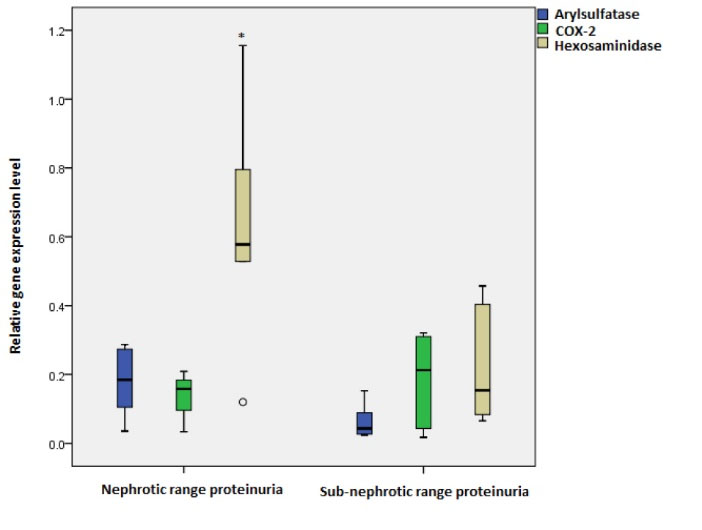

To confirm the value of our target genes and pathways in progression of FSGS, we investigated these genes in patients considering 2 clinical factors: range of proteinuria (>3 g/d (nephrotic-range) and < 3 g/d (sub-nephrotic-range)) and eGFR (> 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). The results indicated that the expression level of hexosaminidase was significantly higher in the urinary sediment of patients with nephrotic-range proteinuria compared to the sub-nephrotic group (P value = 0.02 and fold change =3.7) (Fig. 2). In addition, the combination of target genes could improve the prediction of disease severity based on protein excretion by 87% (with sensitivity and specificity of 77% and 100% respectively) in comparison to every single gene alone. The result of ROC analysis for the patients in 2 groups of nephrotic- and sub-nephrotic-range proteinuria is summarized in Table 3. The ROC curves are depicted in Fig. S2.

Fig. 2.

Relative expression level of target genes in FSGS patients with nephrotic range compared with sub-nephrotic range proteinuria. Expression level of hexosaminidase significantly increased in patients with nephrotic range proteinuria (P value = 0.02)*. No significant changes were observed in relative expression of arylsulfatase (P value = 0.09) and COX-2 (P value= 0.79) between 2 sub-groups of patients.

.

Relative expression level of target genes in FSGS patients with nephrotic range compared with sub-nephrotic range proteinuria. Expression level of hexosaminidase significantly increased in patients with nephrotic range proteinuria (P value = 0.02)*. No significant changes were observed in relative expression of arylsulfatase (P value = 0.09) and COX-2 (P value= 0.79) between 2 sub-groups of patients.

Table 3.

The results of ROC analysis and U-test for discrimination of patients with nephrotic and sub-nephrotic proteinuria

|

Gene

|

Specificity

|

Sensitivity

|

AUC

|

| Arylsulfatase |

54% |

100% |

0.74 |

| Hexosaminidase |

75% |

100% |

0.81 |

| COX-2 |

70% |

50% |

0.55 |

| Arylsulfatase + Hexosaminidase |

72% |

100% |

0.78 |

| Arylsulfatase + Hexosaminidase + COX-2 |

77% |

100% |

0.87 |

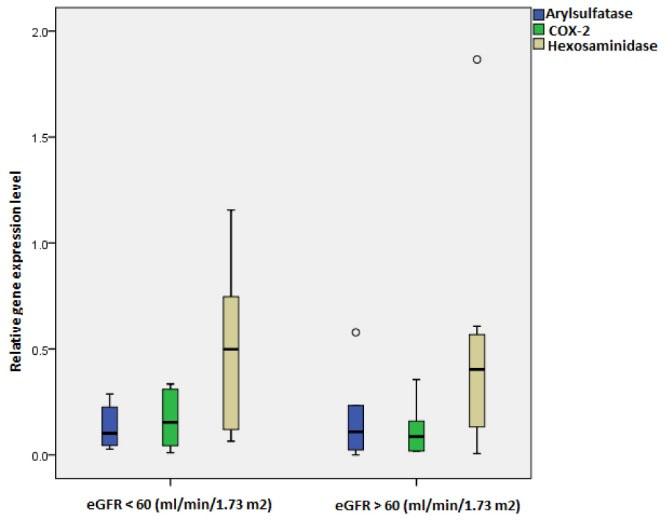

The expression level of target genes based on eGFR was not significantly different in the patients with mild decline of renal function (eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) compared to severe decline of renal function (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) (Fig. 3), however, the panel of combination of these target genes predicted the patients with severe disease with AUC of 74% (with sensitivity and specificity of 60% and 90%, respectively) (Table 4). The ROC curves are depicted in Fig. S3.

Fig. 3.

Relative expression level of target genes in FSGS patients with eGFR > 60 and < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. No significant changes were observed between patients with different disease severities (Arylsulphatase P value = 0.8, Hexosaminidase P value = 0.8, COX-2 P value = 0.8).

.

Relative expression level of target genes in FSGS patients with eGFR > 60 and < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. No significant changes were observed between patients with different disease severities (Arylsulphatase P value = 0.8, Hexosaminidase P value = 0.8, COX-2 P value = 0.8).

Table 4.

The results of ROC analysis of target genes for discrimination of patient groups with different eGFR levels (< 60 and > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2)

|

Gene

|

Specificity

|

Sensitivity

|

AUC

|

| Arylsulfatase |

17% |

100% |

0.46 |

| Hexosaminidase |

85% |

41% |

0.57 |

| COX-2 |

50% |

100% |

0.58 |

| Arylsulfatase + Hexosaminidase |

50% |

83% |

0.6 |

| Arylsulfatase + Hexosaminidase + COX-2 |

60% |

90% |

0.74 |

The correlation analysis indicated a significant positive association between hexosaminidase and proteinuria. There was also a significant positive correlation between COX-2 and interstitial inflammation, while a negative correlation was observed between COX-2 and serum creatinine (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation analysis of target genes with clinical and histopathological features in the patients group

|

|

Proteinuria

|

Interstitial inflammation

|

eGFR

|

Serum creatinine level

|

Glomerular sclerosis

|

IFTA

|

Mesangial hypercellularity

|

| Arylsulphatase |

r = 0.4, P = 0.17

|

r = 0.009, P = 0.97

|

r = 0.025, P = 0.94

|

r = -.026,

P = 0.92

|

r = -0.05,

P = 0.85

|

r = 0.087, P = 0.72

|

r = -0.22,

P = 0.38

|

| Hexosaminidase |

r = 0.58, P = 0.03*

|

r = -0.08, P = 0.75

|

r = 0.08, P = 0.79

|

r = 0.072,

P = 0.77

|

r= 0.6,

P = 0.8

|

r = 0.3, P = 0.19

|

r = -0.025,

P = 0.91

|

| Cyclooxygenase-2 |

r = -0.1, P = 0.78

|

r = 0.53, P = 0.035*

|

r = -0.19, P = 0.7

|

r = -0.58,

P = 0.019*

|

r = 0.18,

P = 0.5

|

r = 0.039, P = 0.89

|

r = 0.03,

P = 0.91

|

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IFTA, interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy.

The linear regression analysis revealed the importance of COX-2 in the prediction of eGFR in the patients (P value = 0.005).

Discussion

Chondroitin sulfate is one of the major molecules of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and consists of repetitive disaccharide units of N-acetylgalactosamine.

27

GAGs are complex linear anionic carbohydrates which are found on cell surfaces or in the extracellular matrix, and play important roles in cell growth, differentiation, morphogenesis, cell migration, and infection.

27,28

The most important enzymes in sulphation and degradation of chondroitin sulphates are arylsulphatase and hexosaminidase that were strongly significant in our previous study.

23

In the present study, we examined the hypothesis of the involvement of chondroitin sulfate degradation pathway by evaluating the expression level of these 2 enzymes in the urine sediment of patients with FSGS. Our results indicated a significant increase in the level of hexosaminidase expression in patients with nephrotic compared with sub-nephrotic proteinuria (Fig. 2). The same trend was observed in the expression level of arylsulfatase, however, the P value was not significant. Correlation analysis also revealed a positive correlation between hexosaminidase expression level and proteinuria in the patients (Table 5). These findings indicate the importance of these 2 target enzymes from chondroitin sulfate degradation pathway in the progression of FSGS. Since GAGs are known as renoprotective molecules against the progression of renal diseases,

29

whose function is important in preservation of integrity, thickness, and permselectivity of the endothelial glycocalyx,

30,31

one can postulate that degradation of GAGs (and especially chondroitin sulfate) by activation of enzymes such as arylsulfatase and hexosaminidase could damage the protective GAGs and end up with proteinuria and renal injury. This finding is in line with that of a study by Hultberg et al who showed the importance of hexosaminidase in proteinuric diseases,

32

however, our results are proposed for the first time in FSGS and in the sediment of urine.

COX-2 (also known as prostaglandin G/H synthase 2) is one of the most important enzymes in the production procedure of eicosanoids,

33

that is induced by inflammatory mediators and mitogens, and hence plays a key role in pathophysiologic processes.

34

It is well characterized that prostaglandins (one type of eicosanoids that are produced by COX-2), especially prostaglandin I2 (PGI2), act locally on the glomerulus and derive from COX-2 expressed in the macula densa.

35

Therefore, their function is important for the homeostasis of the renal condition, and their perturbation contributes to the pathogenesis of renal vascular hypertension through stimulating renal renin synthesis and release.

36

COX-2 is also highly inducible in podocytes, mesangial cells, renal tubular epithelial cells, and interstitial cells,

37

and plays important roles in the kidney such as regulating renin release,

38

water/salt metabolism,

39,40

and kidney development.

41,42

Perturbation in the metabolism of eicosanoids particularly under the influence of COX-2 and PGI2 synthase were also shown to be important in the pathogenesis of FSGS in our previous in silico study.

23

The experiment on mRNA level of COX-2 in this study showed a non-significant decrease in FSGS patients compared to control subjects (Fig. 1), whereas no signal was detected for prostaglandin I2 synthase. This decrement of COX-2 expression is in line with the studies of Morham et al, Norwood et al and Dinchuk et al, which suggested COX-2 deficiency could induce renal abnormalities and development of nephropathy in experimental models.

43-45

In spite of these findings, there are contradictory studies on the pathologic effect of the increase of COX-2 expression in renal diseases such as diabetic nephropathy,

46

and accordingly COX-2 inhibitor drugs are suggested for reducing proteinuria and effects of renal dysfunction.

47,48

Altogether it seems that COX-2 plays a complicated role in renal pathophysiology which highly depends on situation, tissue, and etiology of the disease. For instance, downregulation of COX-2 in certain conditions along with other factors might end up with FSGS, while upregulation of COX-2 in the presence of other pathologic factors develops diabetic nephropathy. In general, this finding beside significant correlation of COX-2 with serum creatinine level and interstitial inflammation (Table 5) and significant regression with eGFR, unravels the pathologic role of COX-2 in the progression of FSGS. Furthermore, ROC analyses revealed that combination of arylsulphatase, hexosaminidase, and COX-2 has a better ability in the diagnosis of patients from healthy controls, as well as diagnosis of patients with more severe disease than those with single genes (Tables 2-4). Therefore, this panel of genes could be considered as non-invasive biomarker candidates for FSGS. The high AUCs of this triple panel in discrimination of patients with higher proteinuria and severe decline of eGFR shows that these genes along with each other could be more effective in the progression of the disease.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is confirmed the role of chondroitin sulfate degradation and eicosanoids mechanism in the pathogenesis of FSGS, and therefore, a panel of three biomarker candidates is suggested for non-invasive diagnosis of this disease.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the Chronic Kidney Disease Research Center (CKDRC) and Urology and Nephrology Research Center (UNRC), Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, for the financial support. This study is part of the MSc thesis of Hootan Yazdani.

Funding sources

This study was funded by the Chronic Kidney Disease Research Center (CKDRC) at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with grant no. 462/4.

Ethical statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Ethical Standards of the Institutional and/or National Research Committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The signed informed consent was obtained from all participants. This research was approved by the Local Ethics Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of interests

This study presented as poster in 15th Iranian National Congress of Biochemistry and 6th International Congress of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology that was held on 25-28th August 2018, in Isfahan.

Authors contribution

SK; conceptualization, experiments design, draft preparation. MNaj; data handling, provision of study materials and equipment. MNaf; project administration, supervision, HYK; data presentation, collection of clinical data, and contribution in data analysis. NB; study consultation. MP; study validation, pathological diagnosis of biopsy samples.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file 1 contains Table S1 and Figures S1-S3.

(pdf)

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

simple

-

√ The pathways of chondroitin sulfate degradation and

eicosanoid metabolism contribute to FSGS pathogenesis and

progression of this disease.

-

√ A panel of three enzymes including arylsulfatase,

hexosaminidase, and cyclooxygenase-2 is sensitive to the

non-invasive diagnosis of FSGS.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ Cyclooxygenase-2 has a significant relationship with

clinical (i.e. serum creatinine and eGFR) and histological

features (i.e. interstitial inflammation) of patients with FSGS

and hence is a valuable target for further analyses on the level

of protein in the larger cohort.

References

- Fogo AB. Causes and pathogenesis of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2015; 11:76. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.216 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kriz W. The pathogenesis of ‘classic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis—lessons from rat models. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:vi39-vi44. [ Google Scholar]

- de Mik SM, Hoogduijn MJ, de Bruin RW, Dor FJ. Pathophysiology and treatment of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: the role of animal models. BMC Nephrol 2013; 14:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-74 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Brenner BM. Nephron adaptation to renal injury or ablation. Am J Physiol 1985; 249:F324-F37. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1985.249.3.F324 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McCarthy ET, Sharma M, Savin VJ. Circulating permeability factors in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:2115-21. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03800609 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rood IM, Deegens JK, Wetzels JF. Genetic causes of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: implications for clinical practice. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:822-90. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr771 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jefferson JA, Shankland SJ. The pathogenesis of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2014; 21:408-16. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.05.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wei C, El Hindi S, Li J, Fornoni A, Goes N, Sageshima J. Circulating urokinase receptor as a cause of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Med 2011; 17:952. doi: 10.1038/nm.2411 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Clement LC, Avila-Casado C, Macé C, Soria E, Bakker WW, Kersten S. Podocyte-secreted angiopoietin-like-4 mediates proteinuria in glucocorticoid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Nat Med 2011; 17:117. doi: 10.1038/nm.2261 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kestilä M, Lenkkeri U, Männikkö M, Lamerdin J, McCready P, Putaala H. Positionally cloned gene for a novel glomerular protein—nephrin—is mutated in congenital nephrotic syndrome. Mol Cell 1998; 1:575-82. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80057-X [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Boute N, Gribouval O, Roselli S, Benessy F, Lee H, Fuchshuber A. NPHS2, encoding the glomerular protein podocin, is mutated in autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Nat Genet 2000; 24:349. doi: 10.1038/74166 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hinkes B, Wiggins RC, Gbadegesin R, Vlangos CN, Seelow D, Nürnberg G. Positional cloning uncovers mutations in PLCE1 responsible for a nephrotic syndrome variant that may be reversible. Nat Genet 2006; 38:1397. doi: 10.1038/ng1918 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mucha B, Ozaltin F, Hinkes BG, Hasselbacher K, Ruf RG, Schultheiss M. Mutations in the Wilms' tumor 1 gene cause isolated steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome and occur in exons 8 and 9. Pediatr Res 2006; 59:325. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000196717.94518.f0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zenker M, Aigner T, Wendler O, Tralau T, Müntefering H, Fenski R. Human laminin β2 deficiency causes congenital nephrosis with mesangial sclerosis and distinct eye abnormalities. Human Mol Genet 2004; 13:2625-32. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh284 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ozaltin F, Ibsirlioglu T, Taskiran EZ, Baydar DE, Kaymaz F, Buyukcelik M. Disruption of PTPRO causes childhood-onset nephrotic syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 89:139-47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.026 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gee HY, Saisawat P, Ashraf S, Hurd TW, Vega-Warner V, Fang H. ARHGDIA mutations cause nephrotic syndrome via defective RHO GTPase signaling. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:3243-53. doi: 10.1172/JCI69134 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ashraf S, Gee HY, Woerner S, Xie LX, Vega-Warner V, Lovric S. ADCK4 mutations promote steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome through CoQ 10 biosynthesis disruption. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:5179-89. doi: 10.1172/JCI69000 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, Farrington MK, Creazzo T, Hawkins AF. A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science 2005; 308:1801-4. doi: 10.1126/science.1106215 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 2010; 329:841-5. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- D'Agati VD, Kaskel FJ, Falk RJ. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:2398-411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1106556 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12:502-517. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960616 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rich A. A hitherto undescribed vulnerability of the juxtamedullary glomeruli in lipoid nephrosis. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1957; 100:173-86. [ Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi-Jahromi S, Marashi S-A, Kalantari S. A kidney-specific genome-scale metabolic network model for analyzing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Mamm Genome 2016; 27:158-67. doi: 10.1007/s00335-016-9622-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kalantari S, Nafar M, Rutishauser D, Samavat S, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Yang H. Predictive urinary biomarkers for steroid-resistant and steroid-sensitive focal segmental glomerulosclerosis using high resolution mass spectrometry and multivariate statistical analysis. BMC Nephrol 2014; 15:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-141 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Nafar M, Kalantari S, Samavat S, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Rutishuser D, Zubarev RA. The novel diagnostic biomarkers for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. International journal of nephrology 2014; 2014.

- Kim JH, Kim BK, Moon KC, Hong HK, Lee HS. Activation of the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 2003; 64:1715-21. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00288.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sugahara K, Mikami T, Uyama T, Mizuguchi S, Nomura K, Kitagawa H. Recent advances in the structural biology of chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2003; 13:612-20. [ Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Sugahara K, Özbek S. Evolution of glycosaminoglycans: Comparative biochemical study. Commun Integr Biol 2011; 4:150-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Masola V, Zaza G, Gambaro G. Sulodexide and glycosaminoglycans in the progression of renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29:i74-i9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft389 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gaddi AV, Cicero AF, Gambaro G. Nephroprotective action of glycosaminoglycans: why the pharmacological properties of sulodexide might be reconsidered. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2010; 3:99. [ Google Scholar]

- Celie JW, Reijmers RM, Slot EM, Beelen RH, Spaargaren M, ter Wee PM. Tubulointerstitial heparan sulfate proteoglycan changes in human renal diseases correlate with leukocyte influx and proteinuria. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008; 294:F253-F63. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00429.2007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hultberg B. Urinary excretion of β-hexosaminidase in different forms of proteinuria. Clin Chim Acta 1980; 108:195-9. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(80)90005-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hao C-M, Breyer M. Physiologic and pathophysiologic roles of lipid mediators in the kidney. Kidney Int 2007; 71:1105-15. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002192 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Smith WL, Langenbach R. Why there are two cyclooxygenase isozymes. J Clin Invest 2001; 107:1491-5. doi: 10.1172/JCI13271 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Harris RC, McKanna JA, Akai Y, Jacobson HR, Dubois RN, Breyer MD. Cyclooxygenase-2 is associated with the macula densa of rat kidney and increases with salt restriction. J Clin Invest 1994; 94:2504-10. doi: 10.1172/JCI117620 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science 2001; 294:1871-5. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Harris RC. Cyclooxygenase-2 in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000; 11:2387-94. [ Google Scholar]

- Schnermann J, Briggs JP. Tubular control of renin synthesis and secretion. Pflugers Arch 2013; 465:39-51. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1115-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dennis EA, Norris PC. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:511. doi: 10.1038/nri3859 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rios A, Vargas-Robles H, Gámez-Méndez AM, Escalante B. Cyclooxygenase-2 and kidney failure. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2012; 98:86-90. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2011.11.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gambaro G, Venturini AP, Noonan DM, Fries W, Re G, Garbisa S. Treatment with a glycosaminoglycan formulation ameliorates experimental diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 1994; 46:797-806. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.335 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Ye W, Guan G, Dong Z, Jia Z, Yang T. Developmental regulation of calcineurin isoforms in the rodent kidney: association with COX-2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007; 293:F1898-F904. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00360.2007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Morham SG, Langenbach R, Loftin CD, Tiano HF, Vouloumanos N, Jennette JC. Prostaglandin synthase 2 gene disruption causes severe renal pathology in the mouse. Cell 1995; 83:473-82. [ Google Scholar]

- Norwood VF, Morham SG, Smithies O. Postnatal development and progression of renal dysplasia in cyclooxygenase-2 null mice. Kidney Int 2000; 58:2291-300. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00413.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dinchuk JE, Car BD, Focht RJ, Johnston JJ, Jaffee BD, Covington MB. Renal abnormalities and an altered inflammatory response in mice lacking cyclooxygenase II. Nature 1995; 378:406. doi: 10.1038/378406a0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jia Z, Sun Y, Liu S, Liu Y, Yang T. COX-2 but not mPGES-1 contributes to renal PGE2 induction and diabetic proteinuria in mice with type-1 diabetes. PloS One 2014; 9:e93182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093182 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fujihara CK, Antunes GR, Mattar AL, Andreoli N, Avancini DM, Malheiros C. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibition limits abnormal COX-2 expression and progressive injury in the remnant kidney. Kidney Int 2003; 64:2172-81. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00319.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cheng H-F, Wang CJ, Moeckel GW, Zhang M-Z, Mckanna JA, Harris RC. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor blocks expression of mediators of renal injury in a model of diabetes and hypertension1. Kidney Int 2002; 62:929-39. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00520.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]