BioImpacts. 10(1):9-16.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2020.02

Original Research

Incorporating ifosfamide into salvia oil-based nanoemulsion diminishes its nephrotoxicity in mice inoculated with tumor

Sahar M. AlMotwaa 1, 2  , Mayson H. Alkhatib 1, 3, *

, Mayson H. Alkhatib 1, 3, *  , Huda M. Alkreathy 4

, Huda M. Alkreathy 4

Author information:

1Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2Chemistry Department, College of Science and Humanities, Shaqra University, Shagra, Saudi Arabia

3Regenerative Medicine Unit, King Fahd Center for Medical Research, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

4Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Introduction:

Nephrotoxicity is one of the major side effects of the chemotherapeutic drug, ifosfamide (IFO). In this study, IFO was solubilized in nanoemulsion (NE) containing salvia (SAL) essential oil to investigate its adverse side effects in mice.

Methods:

One hundred female Swiss albino mice (n = 20/group) were split into five groups. Group I (Normal) received saline solution (0.9% (w/v) NaCl) while groups II-V were intraperitoneally (I.P.) injected with 2.5 × 106 Ehrlich ascetic carcinoma (EAC) cells/mouse. Group II (EAC) represented the untreated EAC-bearing mice. Group III (IFO) was treated with IFO at a dose of 60 mg/kg/d (I.P. 0.3 mL/mouse). Group IV (SAL) was treated with 0.3 mL blank NE-based SAL oil/mouse. Group V (SAL-IFO) was treated with IFO, loaded in 0.3 mL of blank SAL-NE, at a dose of 60 mg/kg/d (I.P. 0.3 mL/mouse). Groups III-V were treated for three consecutive days.

Results:

There was a double increase in the survival percentage of the SAL-IFO group (60%) relative to the IFO group (30%). Renal damage with the presence of Fanconi syndrome was indicated in the IFO group through a significant elevation in the levels of serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, urine bicarbonate, and phosphate in addition to a reduced level of glucose compared to the normal group. On the other hand, the administration of SAL-IFO into the mice reversed this effect. Additionally, the oxidative stress in the kidney tissues of the SAL-IFO group was ameliorated when compared to the IFO group.

Conclusion:

Incorporating IFO into SAL-NE has protected the kidneys from the damage induced by IFO.

Keywords: Ehrlich ascites carcinoma, Fanconi syndrome, Oxidative stress, Essential oil, Median survival time

Copyright and License Information

© 2020 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Ifosfamide (IFO), an alkylating antineoplastic agent and a prodrug used in adults and children,

1,2

has a broad-spectrum anticancer activity against solid tumors of soft tissue, bone, and lung.

3

One of the major side effects of IFO is the formation of the cytotoxic metabolite, chloroacetaldehyde (CAA), during the IFO metabolism which may induce nephrotoxicity almost in the form of proximal tubular damage and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) reduction.

4

IFO may cause Fanconi syndromeas a result of the renal damage, characterized by the glycosuria, phosphaturia, aminoaciduria, bicarbonaturia, and kaluria.

Nanoemulsion (NE) is a dispersion system that consists of oil, water, surfactant and most frequently cosurfactant.

5

The diameter of the resulted dispersed nanodroplet is usually in the range of 20-200 nm. The major advantages of NEs in drug delivery system are their ability to improve the drug bioavailability and ameliorate the drug efficacy which leads to the reduction of the total drug dose and hence may result in eliminating the unfavorable side effects of the drug.

5-7

Several studies have formulated IFO in nanocarriers including solid-lipid nanoparticle, nanostructured lipid nanoparticles, self-assembled polymeric nanoparticles, span 80 nano-vesicles, and self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems.

8-12

NEs are considered potential carriers for the essential oils and have several disadvantages due to their hydrophobic nature, volatility, and ability to degradation. NEs may improve the bioefficacy, cellular uptake, and tissue distribution of the essential oils.

13

It has been demonstrated recently that the incorporation of different essential oils into the NEs may induce apoptosis and cytotoxicity in breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and cervical cancer cell line (HeLa).

14,15

Several studies have demonstrated the antitumor potential of the essential oils against a broad spectrum of cancers.

16

Recently, a large number of research studies have reported the potent effect of salvia (SAL) plant as anticancer, antimicrobial, antimutagenic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory.

17

In this study, IFO loaded in NE containing SAL essential oil, which has anticancer and antioxidant beneficial properties, was evaluated in vivo with the aim to assess the nephrotoxicity effect induced by IFO.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

IFO was purchased from Baxter, US. Span 20 and Tween 80 were obtained from Sigma (Missouri, US). 100% pure SAL (Sage) oil, extracted from Salvia officinalisL. (Lamiaceae) by steam distillation of flowers and leaves, was purchased from Sokar Nabat for Natural Oils (Jeddah, KSA). According to the material safety data sheet, the purchased sage oil contained α-thujone (40.5%), β-thujone (7%), camphor (21%), 1,8-cineole (12%), humulene (5%), -pinene (4%), camphene (5%), limonene (2%), linalool (free and esterified (1%)), and bornyl acetate (2.5% maximum), as determined by the gas chromatography.

Nanoemulsionpreparation

The NE formula (SAL-NE) was produced by mixing 5.5% (wt/wt) of surfactant mixture of Tween 80 and Span 20 in a ratio of 2 to 1, respectively, 1.8% (wt/wt) SAL oil and 92.7% (wt/wt) water, followed by continuous mixing and heating at temperature above 70°C until it transformed from white emulsion to a transparent solution.

18

Experimental design

A total of 100 female Swiss Albino mice, weighing 22–30 g, were provided from King Fahd Center for Medical Research, King Abdulaziz University (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia). The ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee in the Faculty of Medicine at King Abdulaziz University (1-17-01-009-0068). The mice were given ad libitum access to standard pellet food and water and were kept at standard laboratory conditions (25°C and a 12 h light/dark cycle).

The mice were divided into 5 groups, each consisted of 20 mice. Group I (Normal) received saline solution (0.9% (w/v) NaCl) while Groups II-V were intraperitoneally (I.P.) injected with 2.5 × 106 Ehrlich ascetic carcinoma (EAC) cells/mouse suspended in PBS. Group II (EAC) represented the untreated EAC-bearing mice. Groups III-V were inoculated with EAC for 48 hours. Group III (IFO) included EAC-bearing mice treated with IFO at a dose of 60 mg/kg/d (I.P. 0.3 mL/mouse) for three consecutive days.

19

Group IV (SAL) included EAC-bearing mice treated with 0.3 mL/mouse of blank NE based on SAL oil for three consecutive days. Group V (SAL-IFO) included EAC-bearing mice treated with IFO, loaded in 0.3 mL of blank NE, at a dose of 60 mg/kg/d (I.P. 0.3 mL/mouse).

Sample collection and kidney weight ratio

After 5 days, 10 mice from each group were sacrificed after fasting for 12 hours. Following sacrificing the mice, the ascetic fluid, blood, 24-hour urine and organs were collected to perform the biochemical and histological analysis. The kidneys were directly weighted after sacrificing to calculate the organ weight ratio for each mouse by dividing post sacrifices kidney weight on pre-sacrifice bodyweight of the same mouse. Afterward, the kidneys were cut into pieces, parts of them saved in 10% natural formaldehyde for histological examination. The remaining tissue was kept at −80°C for the antioxidant analysis.

Assessment of the therapeutic efficacy of drug formulas

Ten mice from each group were kept for survival study with monitoring of weight and diet for 60 days. The percentage change in body weight was estimated by using the following equation:

The percentage change in body weight (%) =

(Average body weight change per day-Average body weight at first-day )/(Average body weight on first day)

The food intake per day for each mouse was determined by dividing the consumed food (g) by the number of mice in each cage. The mean survival time (MST) for each group was calculated by dividing the sum of the death day of each mouse by the number of mice. The survival percentage was determined at the end of the experiment (60 days) by dividing the number of the survived mice by the total number of mice and multiplying by 100.

Biochemical analysis

Serum and urine analysis

The serum samples were collected for biochemical analysis into heparinized tubes and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 3000 rpm for the kidney function test. The serum level of creatinine (CRT) and glucose (GLU) were measured according to Biodiagnostic kit's instructions (Biodiagnostic Company, Egypt) while blood urea nitrogen (BUN), calcium (Ca+2), magnesium (Mg+2), sodium (Na+) chloride (Cl-), and potassium (K+) were evaluated according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Ltd, USA). The urine samples were collected for 24 hours before scarifying the mice on the fifth day to measure the level of urine bicarbonate (UCO2) and phosphate (Up) as mentioned by the manufacturer’s instructions (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Ltd, USA).

Antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation level in kidney tissues

The homogenate tissues of kidney organs were used for the measurement of reduced glutathione (GSH), glutathione reductase (GR), malondialdehyde (MDA) and catalase according to Biodiagnostic kit's instructions (Biodiagnostic Company, Egypt). In brief, the GSH level was assayed according to the method of Beutler et al.

20

The method measures the ability of GSH to reduce 5,5′dithiobis, 2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) which results in producing a yellow compound that is directly proportional to the amount of GSH in the sample. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm.

The GR enzyme activity was determined according to the methodology of Goldberg et al.

21

GR level was measured through the decrease in the absorbance at 340 nm on the basis of the oxidation of the NADPH to NADPH + which caused the transformation of the oxidized glutathione to the reduced glutathione. The MDA was estimated according to the method of Satoh.

22

It is based on measuring the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reactive product at 534 nm resulted from the reaction of MDA with TBA in an acidic solution at boiling temperature for half an hour. The catalase enzyme activity was determined as described by Aebi.

23

It was assayed at 510 nm based on the ability of catalase to decompose H2O2.

Histopathological examination

Following mice sacrificing, kidneys were collected, cut into small pieces, fixed in 10% formalin, subjected to dehydration in ascending concentrations of alcohol and embedded in paraffin. Afterward, samples were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). Slides were observed by using an inverted light microscope (TH4-200, Olympus optical Co-Ltd, Japan).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the MegaStat Excel (version 10.3, Butler University). Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. The statistical differences between multiple samples were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) while the post-hoc analysis for assessing the differences between two samples was determined by performing the Tuckey simultaneous tests followed by measuring the P-values for the pairwise tests. The statistical differences between the tested samples were classified as significant (0.01≤P <0.05), highly significant (0.001≤P<0.01), and very highly significant (P< 0.001).

Results

Assessment of the therapeutic efficacy of drug formulas

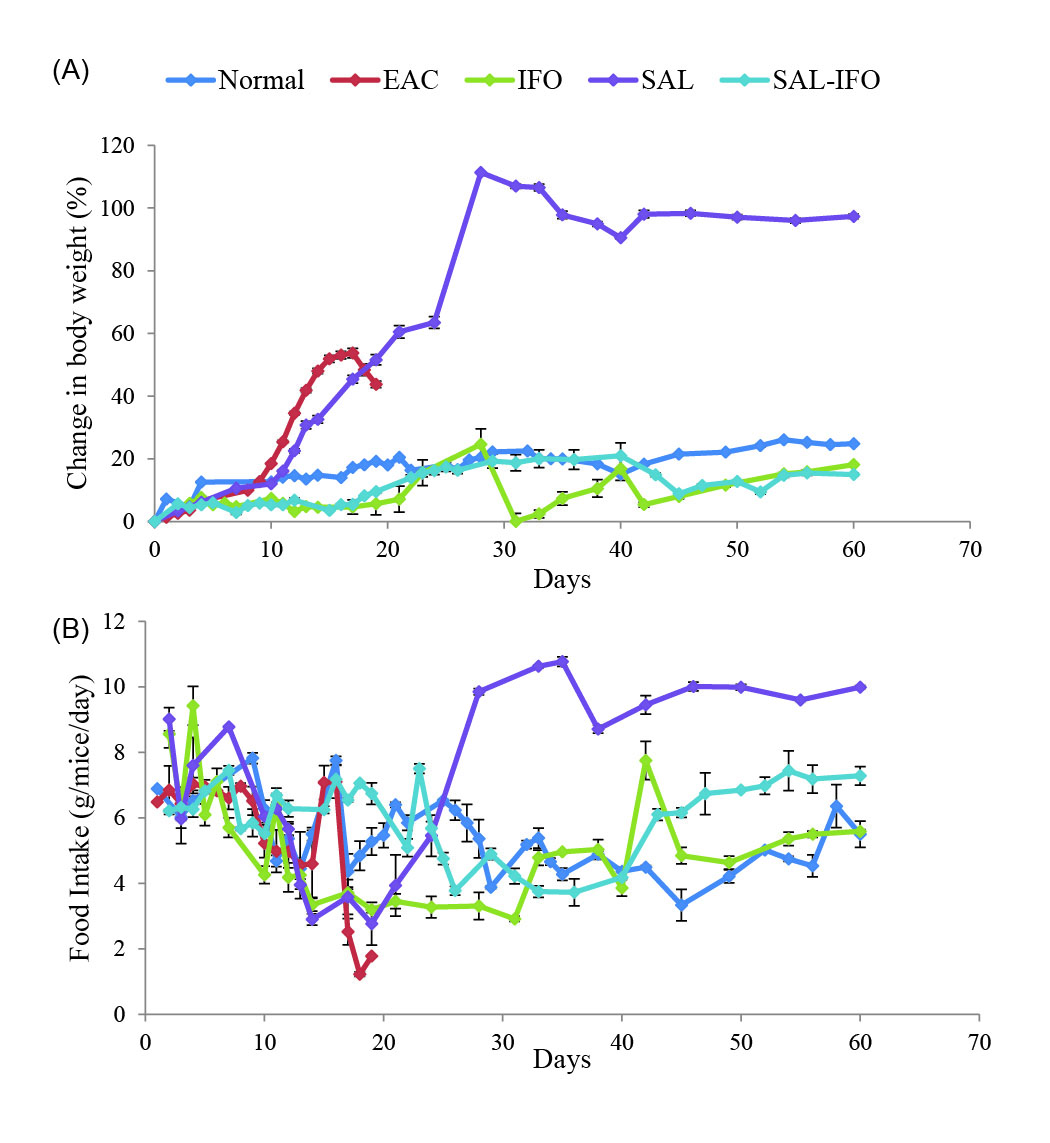

The therapeutic efficacy of the drug formulas was monitored by measuring the MST and the amount of tumor collected following the sacrifice of the mice as illustrated in Table 1. The least amount of tumor was collected from the SAL-IFO group while it had the maximum MST at which its survival percentage (%S) was greater than the IFO group by two-fold. In terms of the effect of drug formulas on the food consumption and % change in body weight (Fig. 1), the entire tested groups were comparable within 60 days except for SAL and EAC groups that had got changed by the time periods. Relative to the other tested groups, SAL group started to consume more food after 28 days (P < 0.05) and markedly gained weight after 11 days (P < 0.001), whereas EAC group had considerably gained weight after 10 days and its food intake had varied after 17 days (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

The effect of drug formulations on the mean of (a) the body weight change (%) and (b) food intake (g/mice/day in EAC bearing mice) of the experimental groups (n = 10 animals/group). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SE).

.

The effect of drug formulations on the mean of (a) the body weight change (%) and (b) food intake (g/mice/day in EAC bearing mice) of the experimental groups (n = 10 animals/group). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SE).

Table 1.

The effect of drug formulations on the collected ascetic fluid of the sacrificed animals, the mean survival time (MST), and survival percentage (%S) for the experimental groups (n =10 animal/group)

|

Animal Groups

|

Ascetic fluid (mL)

|

MST (days)

|

%S

|

| Normal |

|

60 ± 0.00***b,c

|

100 |

| EAC |

1.05±0.03**c

|

18.5 ± 0.3***a,c

|

0 |

| IFO |

1.14±0.05***c

|

32.5 ± 5.07 ***a,b

|

30 |

| SAL |

1.17±0.03*b,***c

|

23.50 ± 2.10***a,c

|

10 |

| SAL-IFO |

0.89±0.057**b

|

36.00 ± 4.90***a,b

|

60 |

Note. The ascetic fluid and MST data were expressed as mean ± SE. Significant differences (*0.01≤ P < 0.05, **0.001≤ P<0.01, and ***P<0.001) were indicated between the individual group and the normal (a), EAC (b), and SAL-IFO (c) groups.

Detection of kidney function

Serum and urine analysis

As illustrated in Table 2, the IFO group exhibited the highest elevations in the serum levels of CRT and BUN when compared to the other tested groups. On the other hand, the administration of SAL-IFO into the mice had reduced the levels of serum CRT and BUN to be remarkably less than IFO groups. The serum level of GLU was markedly decreased in EAC and IFO groups when compared to the normal group whereas the SAL-IFO group reversed this effect to be almost comparable to the normal group. In terms of the electrolytes levels, there were no significant differences in serum Ca+2, Mg+2 and Na+ levels among the experimental groups. However, the Cl- level of SAL-IFO group was lower than that of EAC and IFO groups but it was comparable to the normal group. The K+ level was elevated in SAL and SAL-IFO groups when compared to the other tested groups. On the other hand, the SAL-IFO group had lowered the levels of Up relative to the other tested EAC groups but it was comparable to the normal group. Although the levels of UCO2 were raised in the treated EAC groups relative to the untreated EAC and normal groups, they were significantly reduced in the mice treated with SAL and SAL-IFO when compared to the IFO treated mice.

Table 2.

Drug formulations effect on the kidney function of the tested mice

|

Groups

|

Normal

|

EAC

|

IFO

|

SAL

|

SAL-IFO

|

| CRT (mg/dL) |

118±2***b

|

149.3±8.6***a,c

|

190±1.6***a,b,c

|

106.6±1.7*a,***b,**c

|

120.6±4.3***b

|

| BUN (mmol/L) |

9.1±0.07***b,c

|

10.6±0.06***a,c

|

12±0.11***a,b,c

|

12.5±0.09***a,b,c

|

11.4±0.08***a,b

|

| GLU (mg/dL) |

117.16±2.6***b

|

83.49±3.3***a,c

|

100.16±2.9***a,b,c

|

110.23±4.9**a,**b,*c

|

118.15±0.9***b

|

|

Ca+2 (mmol/L)

|

2.22±0.01 |

2.27±0.009 |

2.150.02 |

2.19±0.008 |

2.05±0.016 |

|

Mg+2 (mmol/L)

|

1.1±0.004 |

1.2±0.007 |

1.1±0.005 |

1.18±0.009 |

1.06±0.007 |

|

Na+ (mmol/L)

|

148±3.3 |

151±1.5 |

149±3.6 |

148±2.9 |

143±4.1 |

| Cl- (mmol/L) |

113±1.4**b

|

118±2.2**a***c

|

116±1.9*b,**c

|

115±1.32**c

|

110±2.3***b

|

|

K+ (mmol/L)

|

4.4±0.29*c

|

4.4±0.32*c

|

4.6±0.1 |

5.1±0.22**a,b

|

5±0.15*a,b

|

|

UCO2 (mmol/L)

|

1±0.0001**b,***c

|

1.5±0.28**a,c

|

2.5±0.28***a,b,**c

|

2±0.0001***a,**b

|

2±0.0001***a,**b

|

|

UP (mmol/L)

|

62.3±1.06***b

|

72.6±2.08***a,c

|

68.19±0.19**a,**b,c

|

64.4±3.6***b,*c

|

59.3±0.3***b

|

| Relative kidney weight |

0.011±0.001 |

0.012±0.001 |

0.013±0.002 |

0.012±0.002 |

0.012±0.001 |

Note. The data were expressed as mean ± SE, (n= 10 animals/group). Significant differences (*0.01≤P <0.05, **0.001≤P<0.01, and ***P<0.001) were indicated between the individual group and the normal (a), EAC (b), and SAL-IFO (c) groups. CRT: creatinine; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; GLU: glucose; Ca+2: calcium; Mg+2: magnesium; Na+: sodium; Cl-: chloride; K+: potassium; UCO2 : urine bicarbonate; Up: phosphate.

Antioxidant activity in kidney tissues

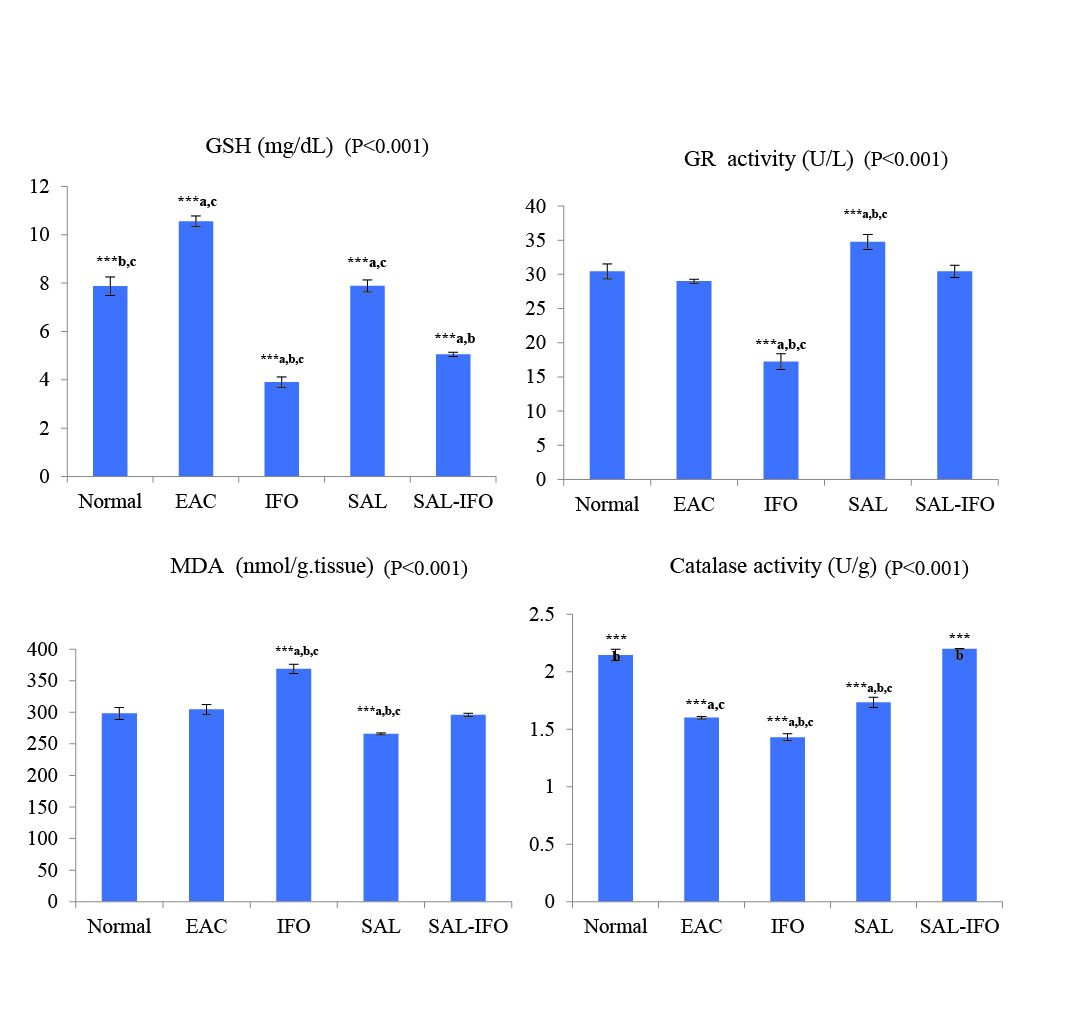

In terms of the percentage changes of the levels of GSH and GR in the kidney tissues relative to the normal group, shown in Fig. 2A-2B, EAC group exhibited a remarkable increase in GSH level (34%) with a slight decrease in GR activity (4%) while the administration of IFO into the mice resulted in significantly depleted GSH (50%) and GR (43%) activity levels. Interestingly, treating the mice with SAL-IFO had reduced this depletion as the level of GSH decreased to about 35% with the restoration of the GR enzyme level. The level of GSH in the SAL group was almost similar to the normal group whereas the GR enzyme level tended to increase.

Fig. 2.

The oxidative stress analysis of the kidney tissues of (a) reduced glutathione (GSH), (b) glutathione reductase (GR), (c) lipid peroxidation (MDA) and (d) catalase enzyme for the experimental groups (n= 10 animals/group). The data were expressed as mean ± SE (error bars). Significant differences (***, P< 0.001) were indicated between the individual group and the normal (a), EAC (b), and SAL-IFO (c) groups.

.

The oxidative stress analysis of the kidney tissues of (a) reduced glutathione (GSH), (b) glutathione reductase (GR), (c) lipid peroxidation (MDA) and (d) catalase enzyme for the experimental groups (n= 10 animals/group). The data were expressed as mean ± SE (error bars). Significant differences (***, P< 0.001) were indicated between the individual group and the normal (a), EAC (b), and SAL-IFO (c) groups.

Regarding the levels of MDA in the kidney tissues, presented in Fig. 2C, they were significantly higher (~ 23%) in IFO treated group than those of the normal group while the combination formula, SAL-IFO, reversed this elevation in the mice to be comparable to the normal and EAC groups. Additionally, SAL-IFO treatment had restored the catalase activity which was comparable to the normal group, but it was considerably decreased in the EAC, IFO and SAL-treated groups by 25%, 33%, and 19%, respectively (Fig. 2D).

Histopathological changes in kidney tissues

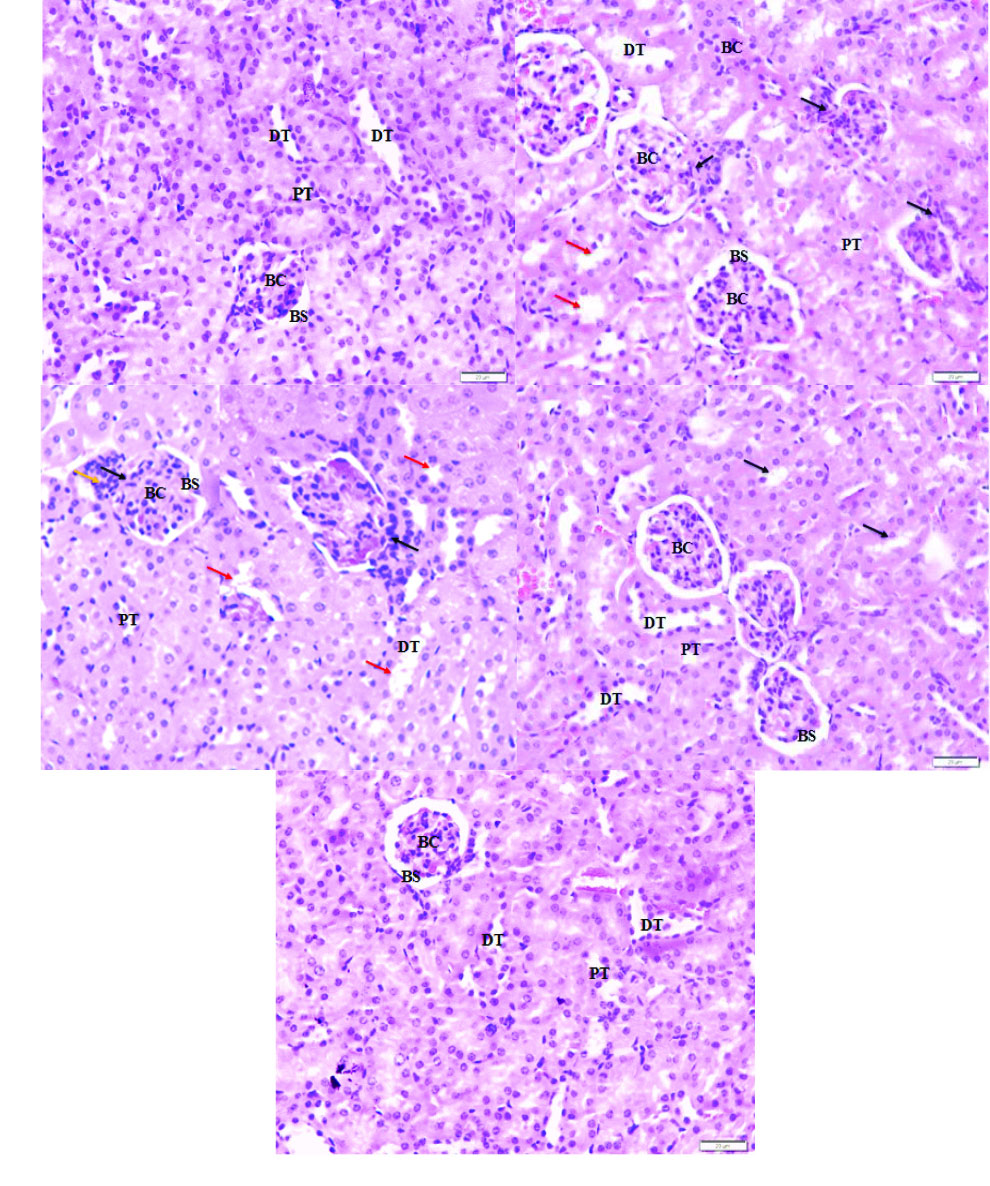

The histological kidney structure of the normal mice, shown in Fig. 3A, exhibited normal Bowman's space surrounding the Bowman's capsule and the renal tubules including proximal tubule and distal tubule. Tissues of EAC tumor group revealed kidney damage including Bowman’s capsule rupture and distortion of the proximal tubule and distal tubule (Fig. 3B). In addition to the changes caused by the tumor, free IFO treatment had caused renal injury due to the presence of lymphocytic infiltration (Fig. 3C). In contrast to the tissues of EAC and IFO groups, the tissues of the mice treated with SAL exhibited moderate damage in Bowman's capsule and renal tubules (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, there were no signs of injury and the structure of the kidney tissue of the SAL-IFO group was ameliorated to be similar to the normal group (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph of the histological structure of kidney for the experimental groups of (a) normal group, displaying normal Bowman's space (BS) surrounding the Bowman's capsule (BC), proximal tubule (PT), and distal tubule (DT). (b) EAC group, showing ruptured Bowman’s capsule (black arrow) with distorted feature of proximal tubule and distal tubule (red arrow), (c) IFO group, showing ruptured Bowman’s capsule (black arrow) with lymphocytic infiltration (orange arrow) and injury in proximal tubule and distal tubule (red arrow), (d) SAL group, showing moderate damage in proximal tubule and distal tubule (black arrow) with slight rupture of Bowman's capsule, and (e) SAL-IFO group, showing nearly the same histological structure as the normal group. H&E stain, 400 x magnifications, 20 µm.

.

Photomicrograph of the histological structure of kidney for the experimental groups of (a) normal group, displaying normal Bowman's space (BS) surrounding the Bowman's capsule (BC), proximal tubule (PT), and distal tubule (DT). (b) EAC group, showing ruptured Bowman’s capsule (black arrow) with distorted feature of proximal tubule and distal tubule (red arrow), (c) IFO group, showing ruptured Bowman’s capsule (black arrow) with lymphocytic infiltration (orange arrow) and injury in proximal tubule and distal tubule (red arrow), (d) SAL group, showing moderate damage in proximal tubule and distal tubule (black arrow) with slight rupture of Bowman's capsule, and (e) SAL-IFO group, showing nearly the same histological structure as the normal group. H&E stain, 400 x magnifications, 20 µm.

Discussion

Alkhatib et al

18

had previously formulated and evaluated the physical characterization and the antitumor activity of SAL and SAL-IFO in MCF-7 and HeLa cells. SAL and SAL-IFO exhibited negative zeta potentials of -7.9±0.11 mV and -1.14 ± 0.08 mV, respectively, while their z-average diameters were in the range of 52.12-56.18 nm and 56.64-64.62 nm, respectively. The polydispersity indexes of the nanodroplet sizes indicated that both of SAL and SAL-IFO were homogeneously distributed. According to the in vitro antineoplastic activity of SAL and SAL-IFO, the incorporation of IFO into SAL-NE had markedly ameliorated the efficacy of IFO. In the current study, the MST of the EAC cell-bearing mice treated with IFO at the dose 60 mg/kg body weight for three consecutive days was greater than SAL-IFO treated groups by two folds. Interestingly, SAL-IFO group exhibited a double higher survival percentage (60%) when compared to the free IFO group (30%). The antitumor activity of IFO is attributed to its ability to alkylate and produce DNA cross-links which cause damage to the DNA.

24

The potent effect of the combination of IFO with the SAL oil-based NE when compared to the free IFO and other tested groups can be due to the antiproliferative action, antimigratory and antiangiogenic effects of SAL.

25,26

Several studies on SAL plant had demonstrated the possible antitumor activity against numerous cancerous cell lines and cancer animal models.

27-33

Besides, drinking Sage tea, a natural substance made from the leaves of SAL officinalis, had been reported to prevent the onset of colon carcinogenesis phases.

34

Growing evidence had shown the ability of SAL to act as a mutagenesis inhibitor through the methanolic extract. It had been demonstrated that SAL had a protective effect against cyclophosphamide- IFO analog- induced genotoxicity in rats.

35

The cytotoxicity and anticancer activity of SAL stem from its constituents. In vitro and in vivo studies reported that the SAL components such as caryophyllene, α-humulene, manool, ursolic acid, and rosmarinic acid had the potential to inhibit tumor cells growth in different cell lines, prevent skin tumors formation, impede angiogenesis phases such as proliferation, migration, adhesion and tube formation.

28,30,32,36-38

One of the major side effects of IFO is nephrotoxicity that can be attributed to the formation of IFO CAA metabolite. As a consequence, glomerular toxicity may develop due to the increase in blood CRT concentration and the reduction of GFR. Additionally, Fanconi syndrome may arise as a result of proximal tubules toxicity which is characterized byaminoaciduria, glycosuria, phosphaturia, bicarbonaturia, and kaluria.

4

Several in vivo studies reported the nephrotoxicity coupled with IFO.

39-42

In the present study, serum CRT, BUN, UCO2, and UP were elevated while serum GLU level had decreased in the IFO group. On the other hand, the combination therapy, SAL-IFO, had eliminated the adverse side effects caused by IFO according to the results of biochemical analysis and histological study of the kidney. Perhaps loading IFO in a NE containing SAL oil had improved the permeation of both IFO and SAL into the cancer cells.

43

It had been reported previously that the nephrotoxicity of IFO metabolites including CAA was attributed to the depletion of stored glutathione associated with significant increases of lipid peroxidation leading to the defect of the antioxidant defense system.

39-42,44

In the current study, glutathione depletion in the IFO treated group was detected by the reduction in GR and catalase activities and elevation in the MDA when compared to the normal group. Interestingly, loading IFO in NE-based SAL oil reversed the side effect of the free IFO on the renal antioxidant defense system. Recently, it had been confirmed by in vitro studies that the incorporation of the essential oils into NE had potentiated their inhibitory actions against the cancer cells growth.

14,15

Cells are protected against the overproduction of reactive oxygen species by natural antioxidants. Several studies reported that SAL possessed a powerful antioxidant activity which was explained by the SAL protective effect on the DNA through its antioxidant activity.

35,45

Furthermore, it had been found that rat hepatocytes resistance against oxidative stress was increased through drinking SAL water.

46

Many reports demonstrated that SAL constituents had powerful antioxidant compounds such as carnosol, rosmarinic acid and caffeic acid.

47-51

Conclusion

The incorporation of IFO into NEcontaining SAL oil had improved the efficacy of IFO and eliminated its nephrotoxicity. It is recommended to make further studies on the adverse effect of IFO-SAL on other organs.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to express a sincere thanks and appreciation to King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology for its financial support.

Funding source

This research project designated by a number (1-17-01-009-0068) was supported by King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology.

Ethical statement

The animals were acclimatized as recommended by King Abdulaziz University's policy to a well-ventilated laboratory environment in polypropylene cages, at a temperature of 25 ± 1° C and facilitated with 12 hours light/dark cycles. They were nourished by standard pellet diet and fresh water before and during the experiment. The animals were kept and handled according to King Abdulaziz University's policy and the international ethical guidelines on the care and use of laboratory animals. The ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee in the Faculty of Medicine at King Abdulaziz University (1-17-01-009-0068).

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contribution

MHA and SMA wrote the concept of the study and designed the experiments. SMA performed the experiments. MHA and SMA analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors drafted and revised the manuscript. The whole study was performed under the supervision of MHA and HMA.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

simple

-

√ IFO drug is an anticancer drug that induces nephrotoxicity

in adults and children.

-

√ NE has nanometric colloidal droplets that have the ability

to transport drugs and hence improve its intracellular

distribution and minimize its side effects.

-

√ SAL oil has an antioxidant and antitumor effect.

-

√ IFO-loaded SAL-NE has improved the apoptotic effect of

IFO in cancer cells.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ The administration of IFO-loaded SAL oil-based NE into

the EAC-bearing mice ameliorated the kidney damage,

eliminated the effect of Fanconi syndrome and attenuated

the cellular oxidative stress resulted from IFO drug. As a

consequence, the survival of the EAC-bearing mice got

improved.

References

- Fleming RA. An overview of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide pharmacology. Pharmacotherapy 1997; 17(5Pt2):146S-154S. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.1997.tb03817.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wagner T. Ifosfamide clinical pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet 1994; 26:439-56. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199426060-00003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Garimella-Krovi S, Springate JE. Effect of glutathione depletion on ifosfamide nephrotoxicity in rats. Int J Biomed Sci 2008; 4:171-174. [ Google Scholar]

- Skinner R. Chronic ifosfamide nephrotoxicity in children Chronic ifosfamide nephrotoxicity in children. Med Pediatr Oncol 2003; 41:190-197. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10336 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal M, Dudhe R, Sharma P. Nanoemulsion: an advanced mode of drug delivery system. Biotech 2015; 5:123-127. doi: 10.1007/s13205-014-0214-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Raj Kumar Mishra GCS, Rekha Mishra. Nanoemulsion: A Novel Drug Delivery Tool. International Journal of Pharma Research & Review 2014; 3:32-43. [ Google Scholar]

- Sahu P, Das D, Mishra VK, Kashaw V, Kashaw SK. Nanoemulsion: a novel eon in cancer chemotherapy. Mini Rev Med Chem 2017; 17:1778-1792. doi: 10.2174/1389557516666160219122755 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Velmurugan R, Selvamuthukumar S. Development and optimization of ifosfamide nanostructured lipid carriers for oral delivery using response surface methodology. Appl Nanosci 2016; 6:159-173. doi: 10.1007/s13204-015-0434-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nakata H, Miyazaki T, Iwasaki T, Nakamura A, Kidani T, Sakayama K. Development of tumor-specific caffeine-potentiated chemotherapy using a novel drug delivery system with Span 80 nano-vesicles. Oncol Rep 2015; 33:1593-1598. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3761 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Yang J-Z, Wang L-F, Zhang Y-J, Lin X-J. Ifosfamide-loaded poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) PLGA-dextran polymeric nanoparticles to improve the antitumor efficacy in Osteosarcoma. BMC Cancer 2015; 15:752-760. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1735-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pandit AA, Dash AK. Surface-modified solid lipid nanoparticulate formulation for ifosfamide: development and characterization. Nanomedicine 2011; 6:1397-1412. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.57 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ujhelyi Z, Kalantari A, Vecsernyés M, Róka E, Fenyvesi F, Póka R. The enhanced inhibitory effect of different antitumor agents in self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems on human cervical cancer HeLa cells. Molecules 2015; 20:13226-13239. doi: 10.3390/molecules200713226 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bilia AR, Guccione C, Isacchi B, Righeschi C, Firenzuoli F, Bergonzi MC. Essential oils loaded in nanosystems: a developing strategy for a successful therapeutic approach. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2014; 2014:651593. doi: 10.1155/2014/651593 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Al-Otaibi WA, Alkhatib MH, Wali AN. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis enhancement in breast and cervical cancer cells upon coadministration of mitomycin C and essential oils in nanoemulsion formulations. Biomed Pharmacother 2018; 106:946-955. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.041 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alkhatib MH, Al-Otaibi WA, Wali AN. Antineoplastic activity of mitomycin C formulated in nanoemulsions-based essential oils on HeLa cervical cancer cells. Chem Biol Interact 2018; 291:72-80. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.06.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gautam N, Mantha AK, Mittal S. Essential oils and their constituents as anticancer agents: a mechanistic view. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014:154106. doi: 10.1155/2014/154106 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani A, Esmaeilizadeh M. Pharmacological properties of Salvia officinalis and its components. J Tradit Complement Med 2017; 7:433-440. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.12.014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alkhatib MH, AlMotwaa SM, Alkreathy HM. Incorporation of ifosfamide into various essential oils-based nanoemulsions ameliorates its apoptotic effect in the cancers cells. Sci Rep 2019; 9:695-704. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37048-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hanly L, Figueredo R, Rieder M, Koropatnick J, Koren G. The effects of N-acetylcysteine on ifosfamide efficacy in a mouse xenograft model. Anticancer Res 2012; 32:3791-3798. [ Google Scholar]

- Beutler E, Duron O, Kelly BM. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J Lab Clin Med 1963; 61:882-888. [ Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D, Spooner R. Methods of enzymatic analysis. Bergmeyer HV 1983; 3:258-265. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-091302-2.X5001-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kei S. Serum lipid peroxide in cerebrovascular disorders determined by a new colorimetric method. Clin Chim Acta 1978; 90:37-43. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(78)90081-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol 1984; 105:121-126. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05016-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Baumann F, Preiss R. Cyclophosphamide and related anticancer drugs. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 2001; 764:173-192. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4347(01)00279-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz M, Mostafaie A, Mansouri K, Bidmeshkipour A, Motlagh HRM, Parvaneh S. In vitro and ex vivo antiangiogenic activity of Salvia officinalis. Phytother Res 2010; 24:1526-1531. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3168 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz M, Bidmeshkipour A, Mostafaei A, Mansouri K, Mohammadi MH. Anti tumor activity of Salvia officinalis is due to its anti-angiogenic, anti-migratory and anti-proliferative effects. Cell Journal 2011; 12:477-482. [ Google Scholar]

- Garcia CS, Menti C, Lambert APF, Barcellos T, Moura S, Calloni C. Pharmacological perspectives from Brazilian Salvia officinalis (Lamiaceae): antioxidant, and antitumor in mammalian cells. An Acad Bras Ciênc 2016; 88:281-292. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201520150344 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- El Hadri A, del Río MÁG, Sanz J, Coloma AG, Idaomar M, Ozonas BR. Cytotoxic activity of α-humulene and transcaryophyllene from Salvia officinalis in animal and human tumor cells. An R Acad Nac Farm 2010; 76:343-356. [ Google Scholar]

- Russo A, Formisano C, Rigano D, Senatore F, Delfine S, Cardile V. Chemical composition and anticancer activity of essential oils of Mediterranean sage (Salvia officinalis L) grown in different environmental conditions. Food Chem Toxicol 2013; 55:42-47. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.036 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jedinak A, Mučková M, Košt’álová D, Maliar T, Mašterová I. Antiprotease and antimetastatic activity of ursolic acid isolated from Salvia officinalis. Z Naturforsch C 2006; 61:777-782. doi: 10.1515/znc-2006-11-1203 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sertel S, Eichhorn T, Plinkert P, Efferth T. Anticancer activity of Salvia officinalis essential oil against HNSCC cell line (UMSCC1). HNO 2011; 59:1203-1208. doi: 10.1007/s00106-011-2274-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xavier CP, Lima CF, Fernandes-Ferreira M, Pereira-Wilson C. Salvia fruticosa, Salvia officinalis, and rosmarinic acid induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation of human colorectal cell lines: the role in MAPK/ERK pathway. Nutr Cancer 2009; 61:564-571. doi: 10.1080/01635580802710733 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kontogianni VG, Tomic G, Nikolic I, Nerantzaki AA, Sayyad N, Stosic-Grujicic S. Phytochemical profile of Rosmarinus officinalis and Salvia officinalis extracts and correlation to their antioxidant and anti-proliferative activity. Food Chem 2013; 136:120-129. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.091 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pedro DF, Ramos AA, Lima CF, Baltazar F, Pereira‐Wilson C. Colon cancer chemoprevention by sage tea drinking: decreased DNA damage and cell proliferation. Phytother Res 2016; 30:298-305. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5531 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- ALKAN FÜ, GÜRSEL FE, ATEŞ A, ÖZYÜREK M, GÜÇLÜ K, Altun M. Protective effects of Salvia officinalis extract against cyclophosphamide-induced genotoxicity and oxidative stress in rats. Turk J Vet Anim Sci 2012; 36:646-654. doi: 10.3906/vet-1105-36 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira PF, Munari CC, Nicolella HD, Veneziani RCS, Tavares DC. Manool, a Salvia officinalis diterpene, induces selective cytotoxicity in cancer cells. Cytotechnology 2016; 68:2139-2143. doi: 10.1007/s10616-015-9927-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yesil-Celiktas O, Sevimli C, Bedir E, Vardar-Sukan F. Inhibitory effects of rosemary extracts, carnosic acid and rosmarinic acid on the growth of various human cancer cell lines. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2010; 65:158-163. doi: 10.1007/s11130-010-0166-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sharmila R, Manoharan S. Anti-tumor activity of rosmarinic acid in 7, 12-dimethylbenz (a) anthracene (DMBA) induced skin carcinogenesis in Swiss albino mice. Indian J Exp Biol 2012; 50:187-194. [ Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Aleksa K, Woodland C, Rieder M, Koren G. N‐Acetylcysteine prevents ifosfamide‐induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2008; 153:1364-1372. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.15 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sayed-Ahmed MM, Darweesh AQ, Fatani AJ. Carnitine deficiency and oxidative stress provoke cardiotoxicity in an ifosfamide-induced Fanconi syndrome rat model. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2010; 3:266-274. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.4.12859 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Şehirli Ö, Şakarcan A, Velioğlu-Öğünç A, Çetinel Ş, Gedik N, Yeğen BÇ. Resveratrol improves ifosfamide-induced Fanconi syndrome in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2007; 222:33-41. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.025 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sener G, Sehirli Ö, Yegen BÇ, Cetinel S, Gedik N, Sakarcan A. Melatonin attenuates ifosfamide‐induced Fanconi syndrome in rats. J Pineal Res 2004; 37:17-25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00131.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sutradhar KB, Amin M. Nanoemulsions: increasing possibilities in drug delivery. Eur J Nanomed 2013; 5:97-110. doi: 10.1515/ejnm-2013-0001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aleksa K, Halachmi N, Ito S, Koren G. A tubule cell model for ifosfamide nephrotoxicity. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2005; 83:499-508. doi: 10.1139/y05-036 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kozics K, Klusová V, Srančíková A, Mučaji P, Slameňová D, Hunáková Ľ. Effects of Salvia officinalis and Thymus vulgaris on oxidant-induced DNA damage and antioxidant status in HepG2 cells. Food Chem 2013; 141:2198-2206. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.089 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Horváthová E, Srančíková A, Regendová-Sedláčková E, Melušová M, Meluš V, Netriová J. Enriching the drinking water of rats with extracts of Salvia officinalis and Thymus vulgaris increases their resistance to oxidative stress. Mutagenesis 2015; 31:51-59. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gev056 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cuvelier ME, Richard H, Berset C. Antioxidative activity and phenolic composition of pilot‐plant and commercial extracts of sage and rosemary. J Am Oil Chem Soc 1996; 73:645-652. doi: 10.1007/BF02518121 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dianat M, Esmaeilizadeh M, Badavi M, Samarbafzadeh A, Naghizadeh B. Protective effects of crocin on hemodynamic parameters and infarct size in comparison with vitamin E after ischemia reperfusion in isolated rat hearts. Planta Med 2014; 80:393-398. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1360383 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Kikuzaki H, Nakatani N. Antioxidant activity of chemical components from sage (Salvia officinalis L) and thyme (Thymus vulgaris L) measured by the oil stability index method. J Agric Food Chem 2002; 50:1845-1851. doi: 10.1021/jf011314o [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Govindaraj J, Pillai SS. Rosmarinic acid modulates the antioxidant status and protects pancreatic tissues from glucolipotoxicity mediated oxidative stress in high-fat diet: streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Mol Cell Biochem 2015; 404:143-159. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2374-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Azevedo MI, Pereira AF, Nogueira RB, Rolim FE, Brito GA, Wong DVT. The antioxidant effects of the flavonoids rutin and quercetin inhibit oxaliplatin-induced chronic painful peripheral neuropathy. Mol Pain 2013; 9:53-66. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-9-53 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]