Bioimpacts. 13(3):183-190.

doi: 10.34172/bi.2022.23528

Original Article

Homozygous mutation in CSF1R causes brain abnormalities, neurodegeneration, and dysosteosclerosis (BANDDOS)

Hossein Daghagh 1, 2  , Haniyeh Rahbar Kafshboran 2, Yousef Daneshmandpour 1, 2, Maryam Nasiri Aghdam 2, Shahrzad Talebian 1, Jafar Nouri Nojadeh 1, Hamid Hamzeiy 2, Saskia Biskup 3, Ebrahim Sakhinia 1, 2, 4, *

, Haniyeh Rahbar Kafshboran 2, Yousef Daneshmandpour 1, 2, Maryam Nasiri Aghdam 2, Shahrzad Talebian 1, Jafar Nouri Nojadeh 1, Hamid Hamzeiy 2, Saskia Biskup 3, Ebrahim Sakhinia 1, 2, 4, *

Author information:

1Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2Tabriz Genetic Analysis Centre (TGAC), Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3CeGaT GmbH, Tuebingen, Germany

4Connective Tissue Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

The CSF1R gene encodes the receptor for colony-stimulating factor-1, the macrophage, and monocyte-specific growth factor. Mutations in this gene cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) with autosomal dominant inheritance and BANDDOS (Brain Abnormalities, Neurodegeneration, and Dysosteosclerosis) with autosomal recessive inheritance.

Methods:

Targeted gene sequencing was performed on the genomic DNA samples of the deceased patient and a fetus along with ten healthy members of his family to identify the disease-causing mutation. Bioinformatics tools were used to study the mutation effect on protein function and structure. To predict the effect of the mutation on the protein, various bioinformatics tools were applied.

Results:

A novel homozygous variant was identified in the gene CSF1R, c.2498C>T; p.T833M in exon 19, in the index patient and the fetus. Furthermore, some family members were heterozygous for this variant, while they had not any symptoms of the disease. In silico analysis indicated this variant has a detrimental effect on CSF1R. It is conserved among humans and other similar species. The variant is located within the functionally essential PTK domain of the receptor. However, no structural damage was introduced by this substitution.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, regarding the inheritance pattern in the family and clinical manifestations in the index patient, we propose that the mentioned variant in the CSF1R gene may cause BANDDOS.

Keywords: BANDDOS, CSF1R, Next generation sequencing, Mutation

Copyright and License Information

© 2023 The Author(s).

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Microglia are macrophage-like cells residing in the brain that enter the central nervous system (CNS) during embryonic development.

1

As the primary immunocompetent cell type of the CNS, they contribute to various important processes, including the development of brain, synaptic plasticity, memory state, and pathophysiological conditions by changing from a surveyor to activated state.

2

Therefore, they can affect neural development, maintenance, and function in healthy and unhealthy circumstances due to their role in CNS damage and repair.

3

The proliferation, development, and survival of microglia requires the activation of a cell-surface receptor named colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) by two cognate ligands, colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) and interleukin-34 (IL-34), which triggers several signaling pathways. The CSF1 cytokine is expressed on microglia, neural progenitor cells (NPCs), and several neuronal subtypes.

4,5

The pleiotropic effects of decrease in CSF1R have been recently studied widely.

Based on the ClinVar database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar), thus far, 62 pathogenic mutations are identified in the CSF1R gene, primarily located in the tyrosine kinase domain of the protein. This domain is located between exons 12 to 21, and most reported mutations take place in exons 18, 19, and 20.

6

These mutations mainly cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) (OMIM 221820), an autosomal dominant progressive disorder of the CNS, with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, including executive dysfunction, memory decline, changes of patient’s personality, motor impairments, seizures, and several other symptoms.

7,8

HDLS is a leukodystrophy, presenting its symptoms with a mean age of onset in the fourth or fifth decade

9

(the age at onset ranges from eight to 78 years),

10

and the average disease course ranges from six to nine years.

11

However, recently, Monies et al in 2017 reported two cases with pediatric phenotypes distinct from HDLS who had homozygous CSF1R mutations. The affected individuals presented a progressive disorder with highly variable phenotypes including severe developmental regression, epilepsy, leukodystrophy, periventricular calcifications, osteopetrosis, structural anomalies of CNS such as agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC) and even death. A more meticulous analysis of their samples unveiled those microglia were completely absent within their brain. Therefore, they suggested that CSF1R deficiency in the homozygous status can cause abnormalities of brain, neurodegeneration, and dysosteosclerosis (BANDDOS; OMIM 618476).

12,13

Next-generation sequencing technology as a precise and reliable option for diagnosing complex genetic disorders and novel causative disease genes can provide potential for diagnosis of CSF1R deficiencies.

14

In this case report, we analyzed a patient and 11 members of his family employing sequencing and bioinformatics analysis in the CSFR1 gene. Our results may help elucidate the etiology of this disease.

Methods

Patient

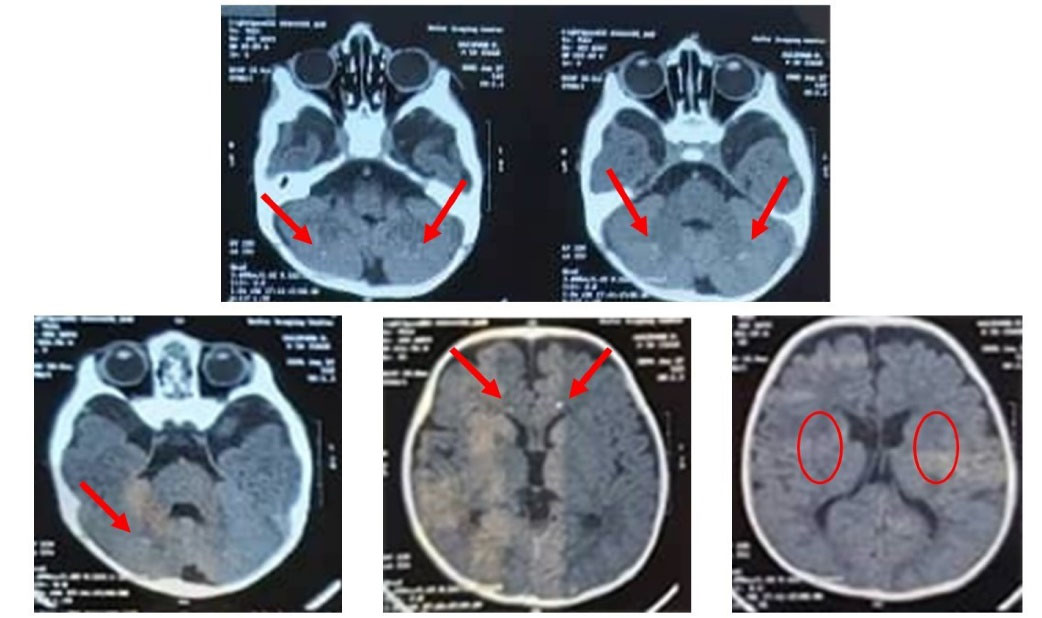

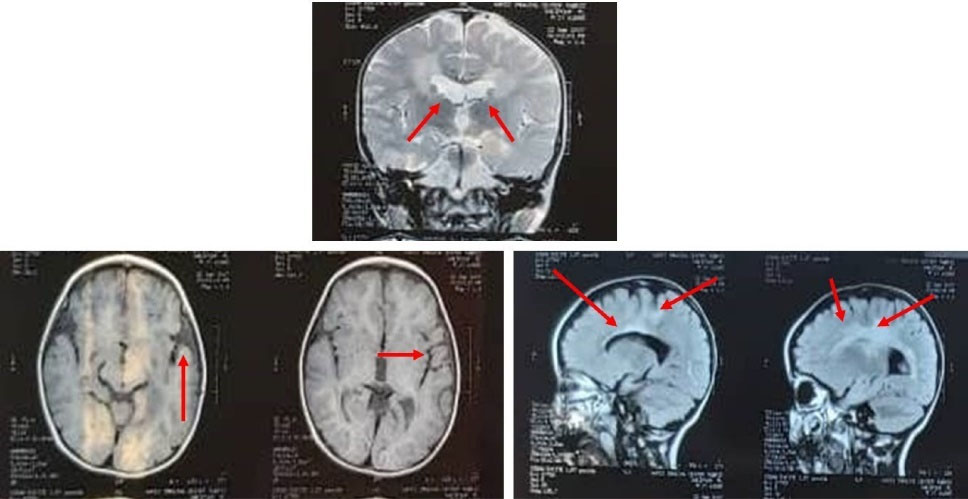

The index patient was a boy, born in 2005 as the first child of healthy consanguineous parents, who referred to Tabriz Genetic Analysis Centre (TGAC) for severe motor dysfunctions, dysphagia, cognitive impairment, and blindness. The patient died at the age of 9 years. The symptoms were initiated with visual problems at one month of age, progressive cognitive decline, gait disturbance, and epileptic seizures above the age of two years. Furthermore, he was admitted several times to the hospital due to shortness of breath and aspiration pneumonia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) scans were obtained. The brain MRI performed at 2 years of age showed confluent high signal foci at proventricular with matter and subcortical region bilaterally. In addition, mild deep white matter volume loss was evident, and cerebral sulci and ventricles were prominent (Fig. 1). Moreover, the cranial CT scan at 5 years of age revealed a decrease in periventricular white matter with considerable calcification in bilateral basal ganglia, grey-white matter junctions, and cerebellar dentate nucleus. Furthermore, the presence of dilatation of the ventricular system and significant cerebellar hypoplasia with mega cisterna magna were observed (Fig. 2). The family pedigree is depicted in Fig. 3A.

Fig. 1.

CT scan findings showing a decreased density in the periventricular white matter with bilateral calcifications within the basal ganglia, cerebellar dentate nucleus, and grey-white matter junctions.

.

CT scan findings showing a decreased density in the periventricular white matter with bilateral calcifications within the basal ganglia, cerebellar dentate nucleus, and grey-white matter junctions.

Fig. 2.

MRI findings showing bilateral, and confluente high signal area in the periventricular white matter and subcortical region, plus mild deep matter volume loss, with the prominence of the sulci, and ventricles.

.

MRI findings showing bilateral, and confluente high signal area in the periventricular white matter and subcortical region, plus mild deep matter volume loss, with the prominence of the sulci, and ventricles.

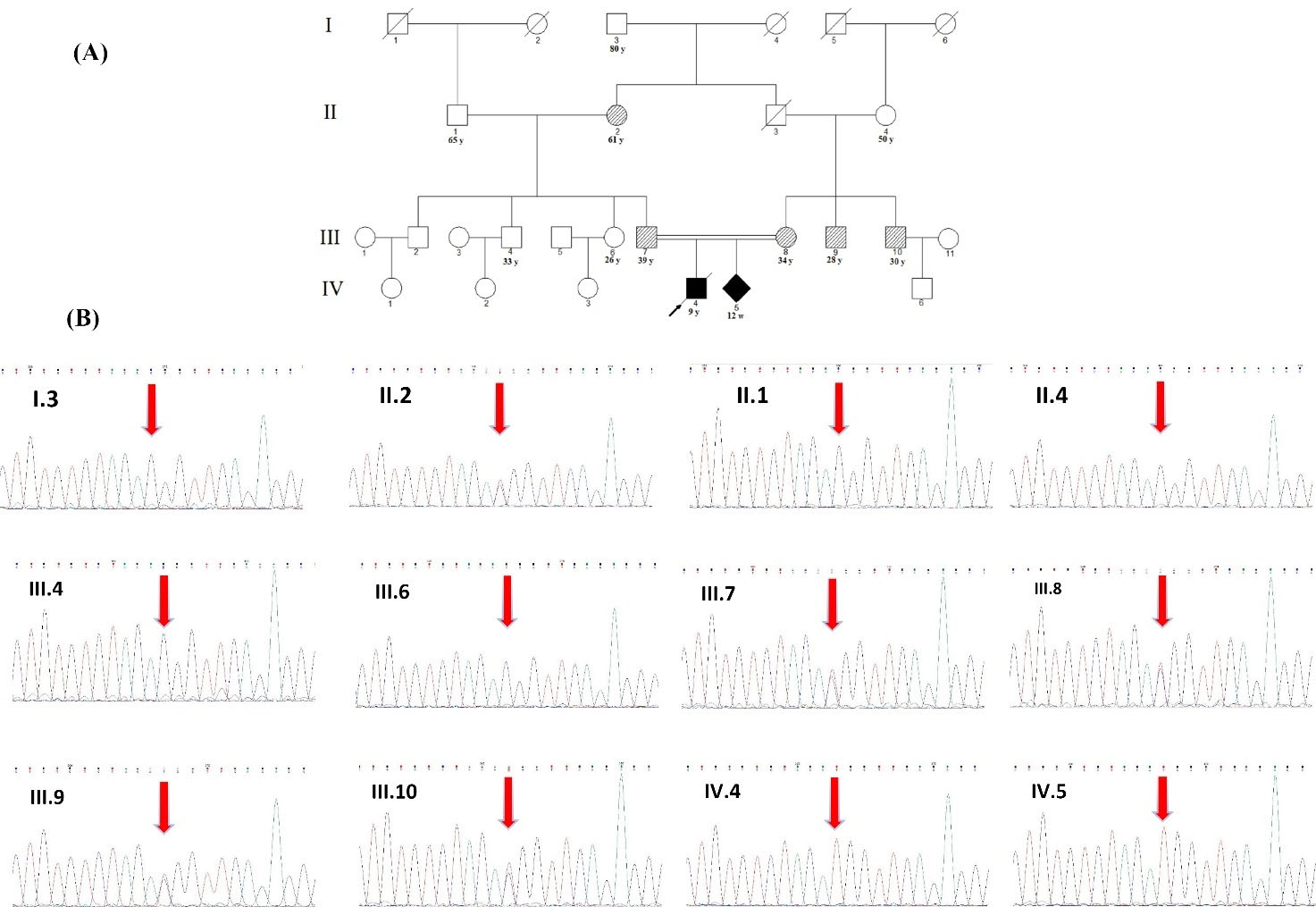

Fig. 3.

Pedigree of the family (A), and sequencing at the novel CSF1R, c.2498C>T; p.T833M variant site (B). A) The filled black or hash pattern symbols indicate the homozygous or heterozygous c.2498C>T; p.T833M variant, respectively. A slash marks the deceased individual, and the arrow indicates proband of the family. The numbers below each symbol show the number and age (y: years, m: months, w; weeks). (B) Sequencing was performed in individuals I:3, II:1, II:2, II:4, III:4, III:6, III:7, III:8, III:9, III:10, IV:4, and IV:5. The DNA for each trace is extracted from blood except for IV:5, which was extracted from chorionic villus sampling (CVS). All of the white and hash pattern symbols are healthy and have not shown any disease symptoms.

.

Pedigree of the family (A), and sequencing at the novel CSF1R, c.2498C>T; p.T833M variant site (B). A) The filled black or hash pattern symbols indicate the homozygous or heterozygous c.2498C>T; p.T833M variant, respectively. A slash marks the deceased individual, and the arrow indicates proband of the family. The numbers below each symbol show the number and age (y: years, m: months, w; weeks). (B) Sequencing was performed in individuals I:3, II:1, II:2, II:4, III:4, III:6, III:7, III:8, III:9, III:10, IV:4, and IV:5. The DNA for each trace is extracted from blood except for IV:5, which was extracted from chorionic villus sampling (CVS). All of the white and hash pattern symbols are healthy and have not shown any disease symptoms.

Human subjects

Ethical issues were considered and informed consent was received from the deceased patient's parents and family members. Following that, genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood, leukocytes, and a CVS sample of the unborn sibling (Table 1).

Table 1.

The clinical information of family members

|

ID

|

Relation to index patient

|

Age

|

Zygosity

|

Symptom

|

Samples of DNA

|

| III:6 |

Paternal aunt |

26 |

Wild type |

Healthy |

Blood |

| II:1 |

Paternal grandfather |

65 |

Wild type |

Healthy |

Blood |

| II:2 |

Paternal grandmother |

61 |

Heterozygous |

Healthy |

Blood |

| III:4 |

Paternal uncle |

33 |

Wild type |

Healthy |

Blood |

| I:3 |

Maternal great-grandfather |

80 |

Wild type |

Healthy |

Blood |

| II:4 |

Maternal grandmother |

50 |

Wild type |

Healthy |

Blood |

| III:9 |

Maternal uncle |

30 |

Heterozygous |

Healthy |

Blood |

| III:10 |

Maternal uncle |

28 |

Heterozygous |

Healthy |

Blood |

| IV:5 |

Sibling |

Prenatal |

Homozygous |

- |

CVS |

| III:7 |

Father |

39 |

Heterozygous |

Healthy |

Blood |

| III:8 |

Mother |

34 |

Heterozygous |

Healthy |

Blood |

NGS-laboratory

Targeted gene sequencing was performed on the deceased patient's sample and 11 family members. The Agilent in solution technology was used to enrich coding and flanking intronic regions, and the sequencing was performed using Illumine HiSeq2500 system.

The panel of analyzed genes consisted of AARS2, ABCD1, ADAR, AIMP1, ALS2, ARSA, ASPA, CLCN2, CSF1R, CYP27A1, CYP7B1, DARS, DARS2, EARS2, EIF2B1, EIF2B2, EIF2B4, EIF2B5, FA2H, FAM126A, FIG4, FOLR1, FUS, GALC, GAN, GBA, GFAP, GJC2, GLB1, HEPACAM, HEXA, HDPD1, L2HGDH, LMNB1, MLC1, NDUFS1, NDUVF1, NOTCH3, PANK2, PLP1, POLR3A, POLR3B, PSAP, RNASEH2B, RNASEH2C, SAMHD1, SERPINI1, SETX, SLC16A2, SOD1, SOX10, SPG11, SPG20, SPG21, SPP1, SUMF1, TARDBP, TREZ1, TUBB4A, VAPB, and ZFYVE26.

Computational analysis

Illumina bcl2fastq (1.8.2) was used for demultiplexing the sequencing reads. Skewer 0.1.116 and Burrows Wheeler Aligner (BWA-mem 0.7.2) were used to remove adapter sequences and mapping reads to the human reference genome (hg19), respectively. Reads which were mapped to more than one location with identical mapping scores were discarded. Duplicates resulting from PCR amplification were removed. Samtools and Varscan were used for variant calling (2.3.3). Technical artifacts were removed (in-house software, CeGaT Tübingen), and the remaining variants were annotated based on several internal and external databases. Moreover, to compute the copy number variations, an internally developed method based on sequencing coverage depth (CeGaT Tübingen) was used.

Diagnostic data analysis

Only variants in the coding region and the flanking intronic regions (±8 bp) with a minor allele frequency (MAF) <5% were evaluated. MAF was taken from the following databases: 1000 genomes, dbSNP, Exome Variant Server, and an in-house database. Variants were termed according to the HGVS recommendations.

Bioinformatics analysis

To predict the effect of mutations on CSFR1 protein, Mutation Taster

15

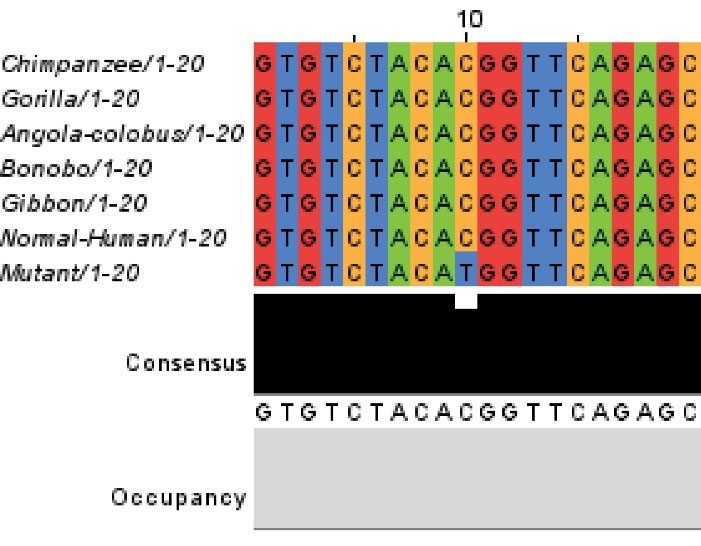

and Polymorphism Phenotyping v2 (PolyPhen-2) databases were used. The DNA and protein sequence of the CSFR1 were aligned with similar species (Chimpanzee, Gorilla, Angola colobus, Bonobo, Gibbon) using Clustal Omega multiple sequence alignment program.

16

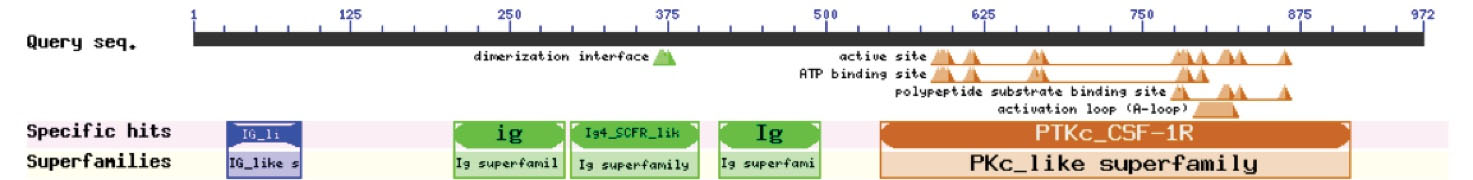

Furthermore, to study involved domains of CSFR1 protein, Conserved Domain Database (CDD) was used.

17

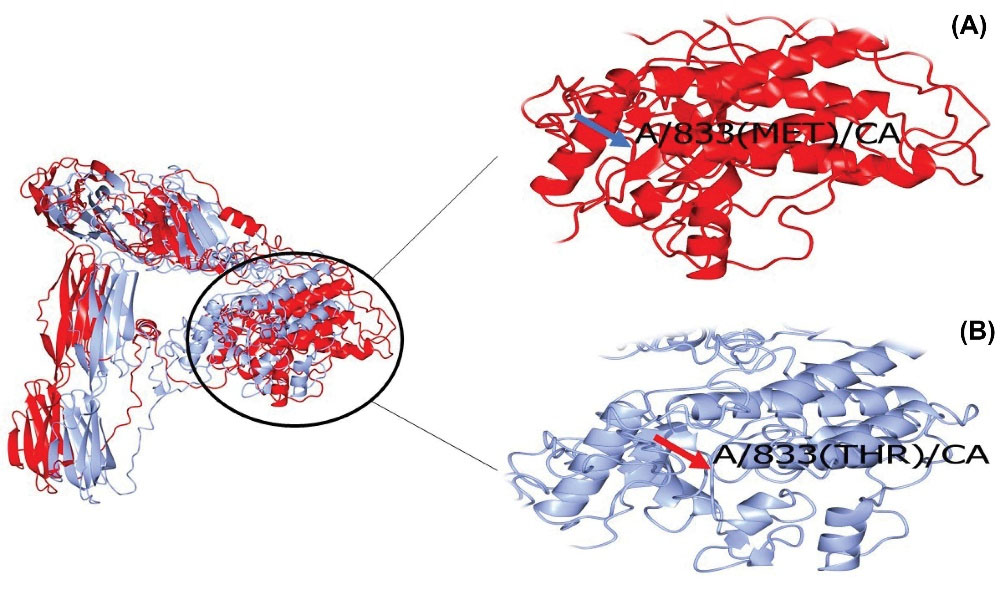

In order to study the effect of the mutation on the 3D structure of the protein, the iterative threading assembly refinement (I-TASSER) server was used for modelling,

18

and the CCP4mg software was used for the depiction of the resulted protein models.

19

The model was provided as input to Missense3D to predict the structural changes resulting from the amino acid substitution.

20

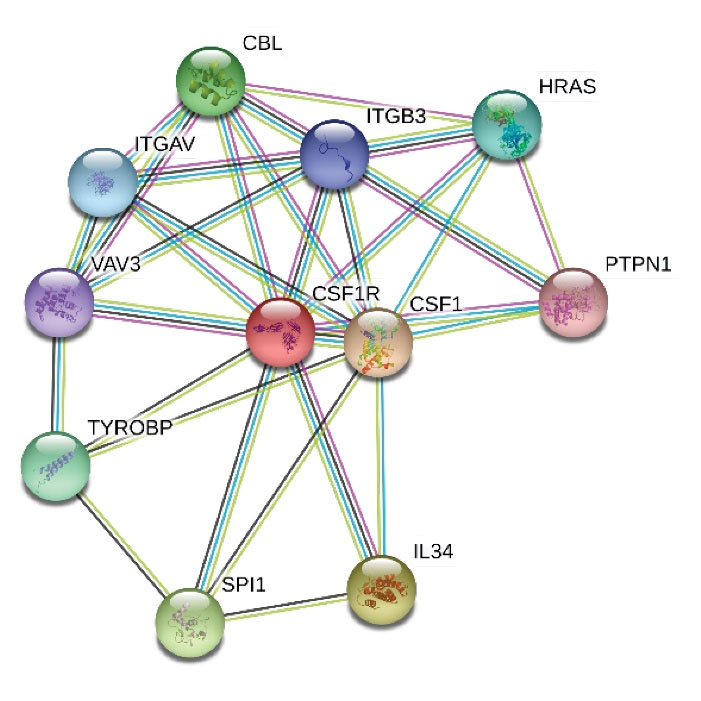

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) were used to study the protein-protein interactions of CSF1R.

Results

Targeted sequencing of the patient

The genetic analysis demonstrated a novel homozygous c.2498C>T; p.T833M variant in exon 19 in the gene CSF1R, which could potentially be causative for the deceased patient. The mutation causes the substitution of an evolutionary, highly conserved amino acid located within the receptor's functionally important tyrosine kinase domain.

The same variant was also detected in a heterozygous state in the paternal grandmother, two maternal uncles, and in the CVS sample of a sibling in a homozygous state (Fig. 3B). This variant has not been reported in the literature so far. Furthermore, it is not present in our local variant database of 232 Azeri Turkish whole-exome sequencing samples (MAF < 0.005 in normal populations - 1000 genomes, dbSNP, Exome Variant Server).

Bioinformatics analysis of the identified mutation

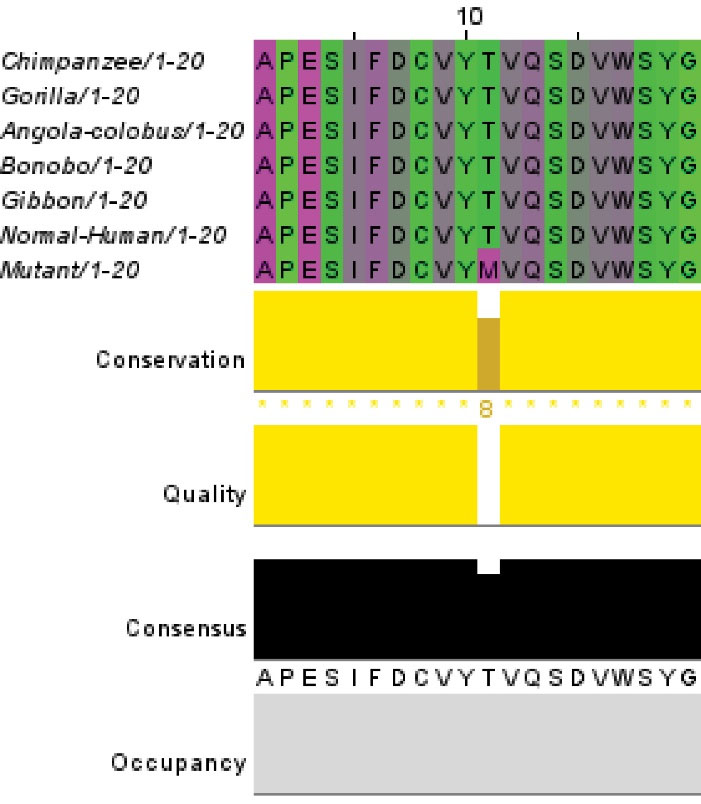

Computational analysis of the identified variant showed that this variant is rated consistently as pathogenic by in silico analyses such as Mutation Taster and PolyPhen-2. DNA and protein alignment results showed the CSFR1 sequence is well-conserved among many species and humans (Figs. 4 and 5). A study of the involved domains of CSFR1 indicated that a novel identified variant is located in the protein kinase domain of the protein (Fig. 6). Missense3D online database revealed no structural damage to the protein. The structure of CSF1R protein is depicted in Fig. 7. The protein-protein interaction network of CSF1R is depicted in Fig. 8.

Fig. 4.

DNA alignment of CSF1R between human and other similar species.

.

DNA alignment of CSF1R between human and other similar species.

Fig. 5.

Protein alignment of CSF1R between human and other similar species.

.

Protein alignment of CSF1R between human and other similar species.

Fig. 6.

The functional domains of CSFR1 protein.

.

The functional domains of CSFR1 protein.

Fig. 7.

3D structure of mutant T833M (Red, A) and normal (Blue, B) CSF1R protein

.

3D structure of mutant T833M (Red, A) and normal (Blue, B) CSF1R protein

Fig. 8.

The protein-protein interaction network of CSF1R mostly participating in brain function.

.

The protein-protein interaction network of CSF1R mostly participating in brain function.

The segregation analysis performed in the context of this molecular analysis revealed that the parents of the deceased patient are both heterozygous carriers of the variant c.2498C>T; p.T833M in exon 19 in the CSF1R gene.

Discussion

As mentioned earlier, more than 60 mutations have been described in CSF1R.

9,13

Most mutations are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and cause HDLS. However, in 2017, Monies et alreported a novel homozygous truncating variant in CSF1R for which the heterozygous parents did not show any manifestations of the HDLS.

12

Following that, Guo et al in 2019 reported CSF1R mutations in six patients with homozygous or compound heterozygous pattern. The inheritance and clinical findings were consistent with "brain abnormalities, neurodegeneration, and dysosteosclerosis" (BANDDOS; OMIM 618476) with highly variable phenotypes. The manifestation of the disease may present at birth or later in childhood or early adulthood.

21

Moreover, Oosterhof et al reported homozygous mutations in the CSF1R gene in two patients.

13

The family under our study, a patient with the aforementioned symptoms was referred to our center with medical documents compatible with leukodystrophy (Figs. 1 and 2). Therefore, due to the heterogeneity of leukodystrophies, we decided to perform a targeted NGS panel in the index patient, his father, his pregnant mother, and the mother's fetus to diagnose the pathogenicity of the disease. We identified a novel homozygous missense variant (c.2498C>T; p.T833M) in exon 19 of the CSF1R gene in our index patient and fetus. Previously, according to the OMIM database, pathogenic mutations in CSF1R just caused HDSL. The father and mother of the patient both were heterozygous for the mutation, and they were 39 and 34 years old, respectively. Therefore, regarding the fact that HDLS is an autosomal dominant adult-onset disease,

4

we investigated eight extra members of this family by targeted NGS (Table 1). Some of them were heterozygous for this mutation; however, they did not show any disease manifestations. Furthermore, some symptoms of the patient were inconsistent with HDLS. Consequently, we omitted the possibility of the HDLS.

In addition to the age of onset of HDLS in our patient and inheritance pattern in his family, we executed additional clinical investigation to reveal the exact cause of the disease. As well as MRI and CT scan outcomes that were more compatible with BANDDOS rather than HDLS, the patient had pectus abnormalities, respiratory problems, aspiration pneumonia, visual problems, and skeletal abnormalities that all confirmed our hypothesis that our patient had BANDDOS. After identifying the cause of the disease, the mother of the patient chose to abort the fetus, who was homozygous for the mutation, after genetic consulting. Following that, performing ovum donation and preimplantation genetic diagnosis, the pregnant woman achieved a normal pregnancy leading to a child who was wild type for the variant. He is now one-year-old and a healthy child.

Bioinformatics analysis indicated a detrimental effect of the novel identified variant on CSF1R protein. Mutation taster and polyphen-2 databases showed the variant to have a pathogenic effect. Alignment results depicted that the sequence of this protein is well conserved among humans and other similar species. Thus, the substitutions may result in a malfunction in the function of the protein. Similar to previous studies, the mutation is located in the tyrosine kinase domain of the protein. In the current study, threonine is replaced with methionine. Threonine is mostly found in the functional domain of the proteins and the kinases commonly phosphorylate it to facilitate signal transduction, while methionine is rarely involved in direct protein function.

22

Concerning the involved domain, the primary function of the CSF1R protein may be affected by this substitution. The online missense3D database indicated no structural damage to the CSF1R protein.

Protein-protein interactions of CSF1R showed interactions with proteins related to the brain and nervous system function (Fig. 8). The ligand of CSF1R, CSF1, is required to differentiate and maintain microglial cells in the developing embryo.

23

Loss of function mutations in TYROBP is related to dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

24,25

VAV3 and HRAS are involved in cerebellar development and brain malignant transformation, respectively.

26,27

Hence, the protein network of CSF1R seems to be involved in multiple brain functions and further research about the role of other components of this network might be of interest.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

√ The CSF1R gene encodes a tyrosine kinase growth factor receptor for colony-stimulating factor-1.

What is new here?

√ A novel homozygous variant identified in the gene CSF1R, c.2498C>T; p.T833M in exon 19.

Conclusion

In summary, due to the compatibility of the BANDDOS with the age of onset and inheritance pattern and in combination with the clinical phenotypes of the deceased patient, we propose that the homozygous variant c.2498C>T; p.T833M in exon 19 of the CSF1R gene can be potentially causative for "Brain abnormalities, neurodegeneration, and dysosteosclerosis" (BANDDOS). This study has some limitations such as insufficient sample and lack of functional in-vitro study to prove the pathogenicity of this variant. All things considered, we hope our results would help have a better understanding of BANDDOS and improved diagnosis in future cases with similar symptoms.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all patients and their families for their participation. Furthermore, we would like to thank Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and Tabriz Genetic Analysis Centre staff for their kind collaboration.

Funding

None.

Ethical Statement

The participation consent has been received from all participants.

Competing Interests

All authors declare there is no conflict of interests.

References

- Green LA, Nebiolo JC, Smith CJ. Microglia exit the CNS in spinal root avulsion. PLoS Biol 2019; 17:e3000159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000159 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- George J, Cunha RA, Mulle C, Amédée T. Microglia‐derived purines modulate mossy fibre synaptic transmission and plasticity through P2X4 and A1 receptors. Eur J Neurosci 2016; 43:1366-78. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13191 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Michell-Robinson MA, Touil H, Healy LM, Owen DR, Durafourt BA, Bar-Or A. Roles of microglia in brain development, tissue maintenance and repair. Brain 2015; 138:1138-59. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv066 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rademakers R, Baker M, Nicholson AM, Rutherford NJ, Finch N, Soto-Ortolaza A. Mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) gene cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Nat Genet 2012; 44:200. [ Google Scholar]

- Chitu V, Gokhan S, Gulinello M, Branch CA, Patil M, Basu R. Phenotypic characterization of a Csf1r haploinsufficient mouse model of adult-onset leukodystrophy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP). Neurobiol Dis 2015; 74:219-28. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lynch DS, Jaunmuktane Z, Sheerin U-M, Phadke R, Brandner S, Milonas I. Hereditary leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids: a spectrum of phenotypes from CNS vasculitis to parkinsonism in an adult onset leukodystrophy series. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016; 87:512-9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-310788 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kleinfeld K, Mobley B, Hedera P, Wegner A, Sriram S, Pawate S. Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with neuroaxonal spheroids and pigmented glia: report of five cases and a new mutation. J Neurol 2013; 260:558-71. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6680-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Inui T, Kawarai T, Fujita K, Kawamura K, Mitsui T, Orlacchio A. A new CSF1R mutation presenting with an extensive white matter lesion mimicking primary progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2013; 334:192-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.08.020 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eichler FS, Li J, Guo Y, Caruso PA, Bjonnes AC, Pan J. CSF1R mosaicism in a family with hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Brain 2016; 139:1666-72. [ Google Scholar]

- Mitsui J, Matsukawa T, Ishiura H, Higasa K, Yoshimura J, Saito TL. CSF1R mutations identified in three families with autosomal dominantly inherited leukoencephalopathy. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2012; 159:951-7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32100 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Foulds N, Pengelly RJ, Hammans SR, Nicoll JA, Ellison DW, Ditchfield A. Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia caused by a novel R782G mutation in CSF1R. Sci Rep 2015; 5:1-7. doi: 10.1038/srep10042 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Monies D, Maddirevula S, Kurdi W, Alanazy MH, Alkhalidi H, Al-Owain M. Autozygosity reveals recessive mutations and novel mechanisms in dominant genes: implications in variant interpretation. Genet Med 2017; 19:1144-50. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.22 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Oosterhof N, Chang IJ, Karimiani EG, Kuil LE, Jensen DM, Daza R. Homozygous mutations in CSF1R cause a pediatric-onset leukoencephalopathy and can result in congenital absence of microglia. Am J Hum Genet 2019; 104:936-47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.03.010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Purnell SM, Bleyl SB, Bonkowsky JL. Clinical exome sequencing identifies a novel TUBB4A mutation in a child with static hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Pediatr Neurol 2014; 50:608-11. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.01.051 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods 2014; 11:361-2. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2890 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Higgins DG. Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein Sci 2018; 27:135-45. doi: 10.1002/pro.3290 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, He J, Lanczycki CJ, Lu S. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res 2017; 45:D200-D3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc 2010; 5:725-38. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McNicholas S, Potterton E, Wilson KS, Noble ME. Presenting your structures: the CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2011; 67:386-94. doi: 10.1107/s0907444911007281 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ittisoponpisan S, Islam SA, Khanna T, Alhuzimi E, David A, Sternberg MJE. Can Predicted Protein 3D Structures Provide Reliable Insights into whether Missense Variants Are Disease Associated?. J Mol Biol 2019; 431:2197-212. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Bertola DR, Takanohashi A, Saito A, Segawa Y, Yokota T. Bi-Allelic CSF1R mutations cause skeletal dysplasia of Dysosteosclerosis-Pyle disease spectrum and degenerative encephalopathy with brain malformation. Am J Hum Genet 2019; 104:925-35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.03.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Betts MJ, Russell RB. Amino Acid Properties and Consequences of Substitutions. In: Barnes MR, Gray IC, eds. Bioinformatics for Geneticists. Wiley; 2003; 10.1002/0470867302.ch14.

- Easley-Neal C, Foreman O, Sharma N, Zarrin AA, Weimer RM. CSF1R Ligands IL-34 and CSF1 Are Differentially Required for Microglia Development and Maintenance in White and Gray Matter Brain Regions. Front Immunol 2019; 10:2199. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02199 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Pottier C, Ravenscroft TA, Brown PH, Finch NA, Baker M, Parsons M, et al. TYROBP genetic variants in early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2016; 48: 222.e9-.e15. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.07.028.

- Paloneva J, Kestila M, Wu J, Salminen A, Bohling T, Ruotsalainen V. Loss-of-function mutations in TYROBP (DAP12) result in a presenile dementia with bone cysts. Nat Genet 2000; 25:357-61. doi: 10.1038/77153 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Quevedo C, Sauzeau V, Menacho-Márquez M, Castro-Castro A, Bustelo XR. Vav3-deficient mice exhibit a transient delay in cerebellar development. Mol Biol Cell 2010; 21:1125-39. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e09-04-0292 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lymbouridou R, Soufla G, Chatzinikola AM, Vakis A, Spandidos DA. Down-regulation of K-ras and H-ras in human brain gliomas. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45:1294-303. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.12.028 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]