Bioimpacts. 2025;15:27735.

doi: 10.34172/bi.2023.27735

Original Article

Long-term pulmonary complications in sulfur mustard-exposed patients: gene expression and DNA methylation of OGG1

Mohammad Saber Zamani Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Tooba Ghazanfari Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 2, *

Author information:

1Department of Biology, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2Immunoregulation Research Center, Shahed University, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

It is well established that tissues exposed to sulfur mustard (SM) generate high levels of reactive oxygen species. This leads to oxidative stress and, ultimately, damage to DNA molecules over the course of time. Additionally, SM, through its alkylating effects, is capable of directly damaging DNA on its own. In cells, these damages trigger a variety of DNA repair pathways, including the base excision repair (BER) pathway. Even so, in the long run, it remains unclear how the BER repair pathways will react.

Methods:

The purpose of this study was to assess the promoter DNA methylation and the mRNA expression of 8-oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1), one of the key components of the BER pathway, in patient PBMCs that were exposed to SM 27 years ago using methylation-sensitive high resolution melting and qPCR. The study was conducted on three groups of participants exposed to SM with mild (n = 20), moderate (n = 24), and severe (n = 20) lung complications.

Results:

Our results showed significant OGG1 mRNA overexpression was observed in moderate groups compared to mild groups (P = 0.036). DNA methylation was also altered in mild-moderate and moderate-severe groups (P < 0.0001 and 0.023, respectively). Although aging was significantly associated with OGG1 mRNA expression, promoter DNA methylation of OGG1 was not associated with its mRNA expression.

Conclusion:

This study revealed differences in OGG1 mRNA expression and DNA methylation among the severity groups of long-term pulmonary complications associated with SM exposure. However, there was no correlation between OGG1 DNA methylation and mRNA expression. Therefore, it appears that other mechanisms may be contributing to the dysregulation of OGG1 mRNA expression.

Keywords: Sulfur mustard, Base excision repair, OGG1, Gene expression, DNA methylation

Copyright and License Information

© 2025 The Author(s).

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

There was no specific grant from any public, private, or not-for-profit funding agency in support of this research.

Introduction

It has been found that sulfur mustard (SM) is a vesicant agent that causes acute effects on humans along with long-term clinical complications. Multiple organs have been found to be affected by SM, including the eyes, the respiratory tract, the dermis, the gastrointestinal tract, and the nervous system, as well as hematocytes, particularly leukocytes. Despite recent efforts to unravel this issue, no clear cellular mechanisms have been identified for the pathogenesis of SM.1,2

According to chemical structure studies, SM functions as an electrophile and can transfer alkyl groups to a wide range of biological macromolecules, including lipids, proteins, and particularly nucleic acids. These findings have led to the classification of SM as an alkylating agent.3,4 The effects of SM on nucleic acids are both direct and indirect. The direct impact of SM on DNA includes the covalent interaction between SM and a single strand of DNA, resulting in lesions such as 7-hydroxyethylthioethylguanine or cross-linking two complementary DNA strands resulting in lesions such as guanine-guanine interaction.5 Alternatively, SM indirectly, through a collection of mechanisms comprising disruption of mitochondria, upregulation in the activity of enzymes producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), and decreased level of intracellular antioxidants, including glutathione (GSH), leads cells toward oxidative stress.6 This oxidative stress eventually caused damage to the DNA molecule and produced specific DNA lesions such as 8-oxoguanine.7

DNA lesions mediated by SM trigger various DNA repair pathways, including base excision repair (BER).8 With the assistance of its main protein, human 8-oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1), the BER pathway is involved in repairing small-scale DNA base lesions such as 8-oxoguanine.9 In this pathway, OGG1recognizes 8-oxoguanine lesions and removes them with the aid of its glycosylase feature, generating apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites in the DNA as a result. The AP sites are then restored by using AP endonuclease, deoxyribophosphate lyase, DNA polymerase, and DNA ligase.

It has been demonstrated that patients with long-term SM complications experience dysregulation of genetic and epigenetic factors. In a study conducted by Salimi et al., the expression of SMAD7, a gene associated with the immune system and signaling pathways, was found to be increased.10 Another study found elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in the serum, a protein associated with programmed cell death.11 Also, in a survey by Vafa et al., methylation changes were observed in the promoter region of the IFNG.12 Furthermore, due to the importance of the DNA repair pathway in patients exposed to SM with long-term complications, an obvious need for genetic and epigenetic research in this field was felt. This study aimed to examine the alteration of mRNA expression levels and DNA methylation status of OGG1, a key constituent of the BER pathway, in individuals exposed to SM about 27 years ago.

Materials and Methods

Statements of ethical approval

The study was conducted at Shahed University’s Immunoregulation Research Center in collaboration with the Science and Research Branch of Islamic Azad University. In order to begin the lab phase of the study, Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research approved the study according to the ethics code IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1398.005. Informed consent was obtained from all participants during the sampling process.

Sample selection and collection

The design and methodology of the Sardasht-Iran Cohort Study of Chemical Warfare Victims are outlined by Ghazanfari et al.13 Based on documents in the medical records verified by the Medical Committee of the Foundation of Martyr and Veterans Affairs, participants in this study were selected from Sardasht men who had been exposed to SM 27 years ago. Additionally, SM exposure documentation, informed consent, and pulmonary complications were required for inclusion. We excluded exposed participants who were taking systemic immunosuppressive drugs from the study to avoid drug interference. In addition, participants whose families had a history of hereditary pulmonary disease were excluded from the study. Medical records and face-to-face interviews were used to collect demographic information. Before sampling, all participants underwent pulmonary examinations, including spirometry. In total, 64 participants with a variety of pulmonary difficulties were selected. Each participant provided fresh blood samples, which were used for DNA and RNA extraction directly.

Sample classification

Samples were classified into three groups: mild, moderate, and severe, based on the severity of pulmonary complications described by Khateri et al.14 The classification criteria are according to Table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria for classifying participants based on pulmonary complications described by Khateri et al

14

|

Sample classification

|

Spirometry

|

Physical exam findings

|

| MILD |

65 = / < FEV1 or 65 = / < FVC |

Abnormal lung sounds |

| MODERATE |

50 = / < FEV1 < 65 or 50 = / < FVC < 65 |

Abnormal lung sounds |

| SEVERE |

40 = / < FEV1 < 50 or 40 = / < FVC < 50 |

Abnormal lung sounds

May include cyanosis intercostal retraction; or tracheal stenosis in bronchoscopy |

Abbreviation: FEV1 = Forced expiratory volume in one second, FVC = Forced vital capacity.

RNA and DNA extraction

Prior to RNA extraction, buffy coats were isolated from whole blood by centrifugation at 300 g for 15 minutes. According to the Protocols, total RNA was extracted from buffy coats using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Cat. No. 74106, Germany). Afterward, DNA was extracted from whole blood according to the manual protocol described previously.15 A spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, NanoDrop 2000c, USA) was used to measure the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the isolated DNA and RNA. The extraction was repeated if the DNA or RNA concentration was less than 50 ng/L. For relative use, RNA and DNA samples were stored at -70 °C.

cDNA synthesis

Using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems, Cat. No. 4368814, USA), 1 μg of the extracted total RNA was synthesized to cDNA. The cDNA synthesis procedure was performed using a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Cat. No. 1861096, USA). Synthesized cDNAs were stored at -20 °C for future use.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

With each participant’s cDNA, qPCR was performed in triplicate. The analysis was conducted using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems Cat. No. 4376600, USA). The qPCR reaction mix was executed at a final volume of 20 μL as outlined below: RealQ Plus 1x Master Mix Green with high ROX (Ampliqon, Cat. No. A325402, Denmark), 0.25 μM forward primer, 0.25 μM reverse primer, 2 μL of 1/10 diluted cDNA and Molecular Biology Grade Water. The cycling conditions were as follows: one cycle of 95 °C for 15 minutes was followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 seconds and 61 °C for 60 seconds. Each cycle was accompanied by the measurement of fluorescent dye levels. The melt curve was then performed following qPCR under the following conditions to ensure that the desired DNA fragment was amplified; a short initial step at 95 °C for 15 seconds followed by 60 °C for 60 seconds and then an increase in temperature from 60 °C to 95 °C with fluorescence dye readings at every 0.3°C increase in temperature. According to previous studies,16 actin beta (ACTB) was selected as a housekeeping gene. The qPCR primer pair sequence applied for ACTB as a housekeeping gene, and the OGG1are as follows: F-ACTB:5’-CATCGAGCACGGCATCGTCA-3', R-ACTB:5’-TAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAAC-3', F-OGG1:5’-ATTCCAAGGTGTGCGACT-3', R-OGG1: 5’-CGGGCGATGTTGTTGTTG-3'. The standard curve was performed to determine the efficiency of primers and evaluate the sensitivity of qPCR.

Fully methylated and fully unmethylated DNA

Fully methylated and fully unmethylated DNA and their combined ratios were employed as controls in methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting (MS-HRM). According to the instructions, methylated and unmethylated DNA were prepared using the CpG Methyltransferase M.SssI (Thermo Scientific, Cat. No. EM0821, USA) and REPLI-g Mini Kit (Qiagen, Cat. No. 150023, Germany) respectively. Then, after bisulfite conversion of fully methylated DNA and fully unmethylated DNA, combinations of 0%, 1%, 2.5%, 5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, and 100% bisulfite-converted methylated DNA were analyzed as controls.

Bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA

EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen, Cat. No. 59104, Germany) was applied to distinguish between methylated and unmethylated cytosines in genomic DNA. A total of 2 g of DNA were extracted from each subject and converted to bisulfite in accordance with the kit's instructions. Sodium bisulfite converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged during the conversion. The bisulfite-converted DNA was finally dissolved in 20μL of elution buffer and stored at -70 °C due to its high sensitivity.

Methylation -sensitive high -resolution melting (MS -HRM)

MS-HRM was executed with 5x HOT FIREPol Eva Green HRM Mix with High ROX (Solis BioDyne, Cat. No. 08-33-00001, Estonia). It was performed in triplicates using StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR (Applied Biosystems Cat. No. 4376600, USA). MS-HRM reaction mix was performed at a final volume of 20 μL as follows: 1x HOT FIREPol Eva Green HRM Mix with High ROX (Solis BioDyne, Cat. No. 08-33-00001, Estonia), 0.25 μM forward primer, 0.25 μM reverse primer, 2 μL of bisulfite converted DNA and Molecular Biology Grade Water. Cycling conditions were as follows: the initial step comprised one cycle of 95 °C for 12 min; followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 61 °C for 20s, and 72 °C for 20 s. Fluorescence dye readings were taken after each cycle. Next, the HRM was performed after PCR according to the following conditions: a short initial step at 95 °C for 15 s with 60 °C for 60 s followed by an increase in the temperature from 60 °C to 95 °C with Fluorescence dye readings by mode of continuous, which is specific for MS-HRM. The design of MS-HRM-specific OGG1 primers is done according to the guidelines previously described17 and is as follows: 5’-AAAGGCGAGTAGTTGGTAGAGAGTTT-3’, 5’-AACCACCGCTCATTTCACCTAAAAATAA-3’ with the length of the 139bp PCR product.

Quantifying HRM results

Quantifying HRM results technique previously mentioned in Bakshi et al study.18 according to the mentioned study, aligned melt curves were used for measures the aligned fluorescence percentage values of each 0%, 1%, 2.5%, 5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, and 100% methylated controls. Then, according to the obtained data set, the related interpolation curve was obtained through the “polyfit” tool by MATLAB software. Finally by placing the average aligned fluorescence percentage of each sample in the interpolation curve, the exact methylation percentage of each sample was obtained.

Data and statistical analysis

The gathering and analysis of real-time PCR data were performed by ExpressionSuite software (Thermo Scientific, release v1.3, USA). Besides, the relative quantification of real-time PCR data was re-verified by Michael W. Pfaffl technique.19 High-Resolution Melt Software (Applied Biosystems Cat. No. A30150, USA) was used to evaluate the MS-HRM data. The normality test of parametric variables was carried out with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Kruskal–Wallis H test and Mann–Whitney U test were performed on real-time PCR data to compare between groups. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test showed a significant difference in DNA methylation status between groups. Spearman and Pearson correlation coefficients were employed based on the normality test result.

Results

Study participants' characteristics

This study consisted of 64 male subjects classified into three groups: mild (n = 20), moderate (n = 24), and severe (n = 20), formed to long-term pulmonary complications associated with SM exposure. According to Table 2, The mean and standard deviation of the BMI and Age of subjects are 27.19 ± 4.27, 49.65 ± 11.37 for the mild group, 28.17 ± 4.09, 53.08 ± 14.06 for the moderate group, and 24.88 ± 4.37, 56 ± 12.6 for the severe group, respectively. More than 75% of the participants in this study did not smoke, and there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of smoking. In addition, the mean and standard deviation of FEV1/FVC ratios (used to diagnose lung disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) are 101.1 ± 5.73, 103.21 ± 14.35, and 78.15 ± 22.41 for mild, moderate, and severe groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Spirometry findings and characteristics of study participants

|

|

Groups

|

P

value

|

|

Mild (n = 20)

|

Moderate (n = 24)

|

Severe (n = 20)

|

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

| Pulmonary Examinations |

FVC % |

99.44 ± 9.44 |

78.46 ± 14.44 |

54.5 ± 18.29 |

0.000 |

| FEV1 % |

91.42 ± 11.03 |

70.34 ± 9.91 |

38.28 ± 9.03 |

0.000 |

| FEV1/FVC % |

101.1 ± 5.73 |

103.21 ± 14.35 |

78.15 ± 22.41 |

0.001 |

| BMI & Age |

BMI |

27.19 ± 4.27 |

28.17 ± 4.09 |

24.88 ± 4.37 |

0.059 |

| Age |

49.65 ± 11.37 |

53.08 ± 14.06 |

56 ± 12.6 |

0.207 |

|

|

|

No. (%)

|

No. (%)

|

No. (%)

|

|

| Smoking |

No |

16(80%) |

18(75%) |

17(85%) |

0.717 |

| Yes |

4(20%) |

6(25%) |

3(15%) |

The one-way ANOVA was used to compare the difference between study groups.

Abbreviation: FEV1 = Forced expiratory volume in one second, FVC = Forced vital capacity, BMI = Body mass index, SD = Standard deviation

Standard curve verification and real-time PCR results

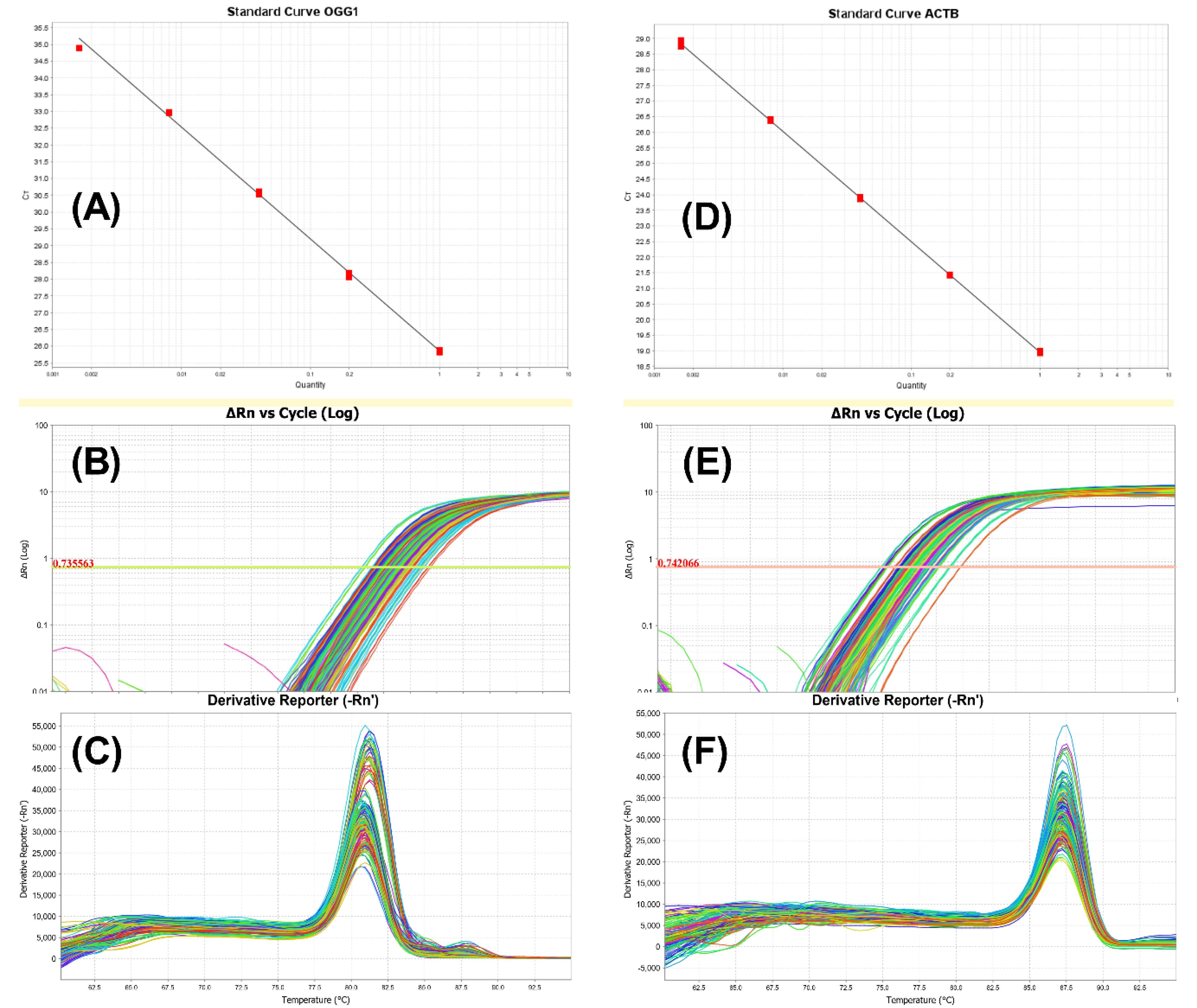

We established standard curves to determine primer efficiency and qPCR sensitivity. The standard curves for OGG1 and ACTB are depicted in sections A and D of Fig. 1. A dilution series of 1:1, 1:5, 1:25, 1:125, and 1:625 is employed for the standard curve. ExpressionSuite (Thermo Scientific, release v1.3, USA) was used for data aggregation and mRNA expression analysis. Sections B and E of Fig. 1 provide amplification plots for all experiments of OGG1 and ACTB, respectively, while sections C and F present aggregated derivative melt curves for OGG1 and ACTB.

Fig. 1.

The accuracy and specificity of real-time PCR results. Graphs A and D represent OGG1 and ACTB standard curves. Efficiency of the PCR reaction is crucial for accurate interpretation of qPCR results, and it is determined by creating a standard curve using a series of diluted DNA samples. Efficiency of the PCR reactions are 99.33% and 91.86% for OOG1 and ACTB. Graphs B and E represent aggregated OGG1 and ACTB amplification plots. The Real-time PCR experiments performed correctly based on the amplification plots. Graphs C and F represent aggregated OGG1 and ACTB derivative melt curves. The presence of unexpected peaks in derivative melt curves may indicate contamination, primer dimers, or non-specific amplification.

.

The accuracy and specificity of real-time PCR results. Graphs A and D represent OGG1 and ACTB standard curves. Efficiency of the PCR reaction is crucial for accurate interpretation of qPCR results, and it is determined by creating a standard curve using a series of diluted DNA samples. Efficiency of the PCR reactions are 99.33% and 91.86% for OOG1 and ACTB. Graphs B and E represent aggregated OGG1 and ACTB amplification plots. The Real-time PCR experiments performed correctly based on the amplification plots. Graphs C and F represent aggregated OGG1 and ACTB derivative melt curves. The presence of unexpected peaks in derivative melt curves may indicate contamination, primer dimers, or non-specific amplification.

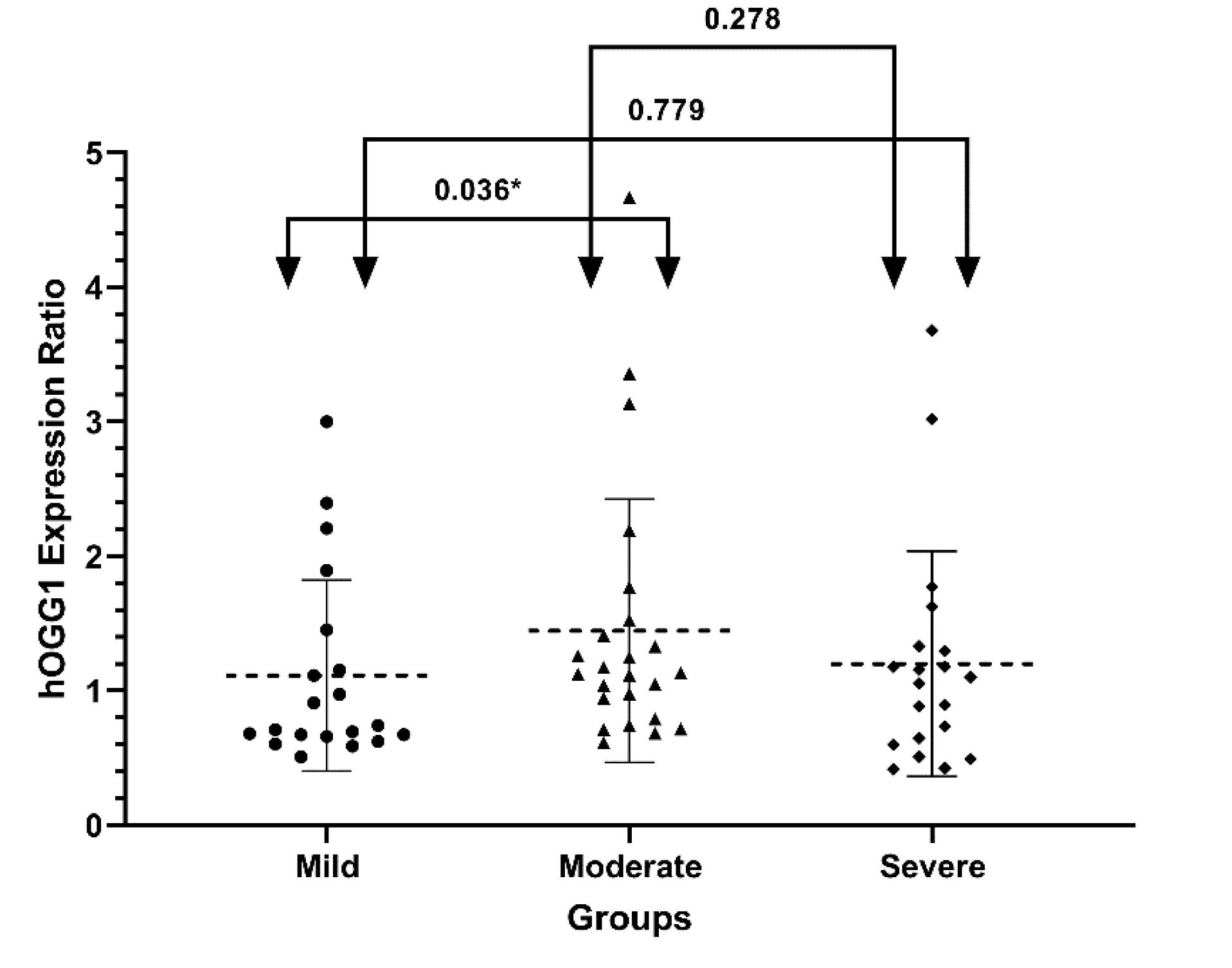

According to our results, only the mild and moderate groups differed significantly when it came to OGG1 mRNA expression. The P-values between mild and moderate, mild and severe, and moderate and severe groups are respectively 0.036, 0.779, and 0.278. Fig. 2 illustrates the mean and standard deviation of OGG1 mRNA expression ratio for all three groups using a dot plot.

Fig. 2.

OGG1 mRNA expression in SM-exposed patients with diverse pulmonary complications. OGG1 mRNA expression ratios in mild (n = 20), moderate (n = 24), and severe (n = 20) groups of participants exposed to SM are presented as dot plots (mean and standard deviation). Real-time PCR is used to evaluate gene expression. ACTB is considered as a reference gene. Mann–Whitney U test were performed to compare between groups. the arrows and numbers indicate the P-value between the groups.

.

OGG1 mRNA expression in SM-exposed patients with diverse pulmonary complications. OGG1 mRNA expression ratios in mild (n = 20), moderate (n = 24), and severe (n = 20) groups of participants exposed to SM are presented as dot plots (mean and standard deviation). Real-time PCR is used to evaluate gene expression. ACTB is considered as a reference gene. Mann–Whitney U test were performed to compare between groups. the arrows and numbers indicate the P-value between the groups.

MS-HRM standard curves and results

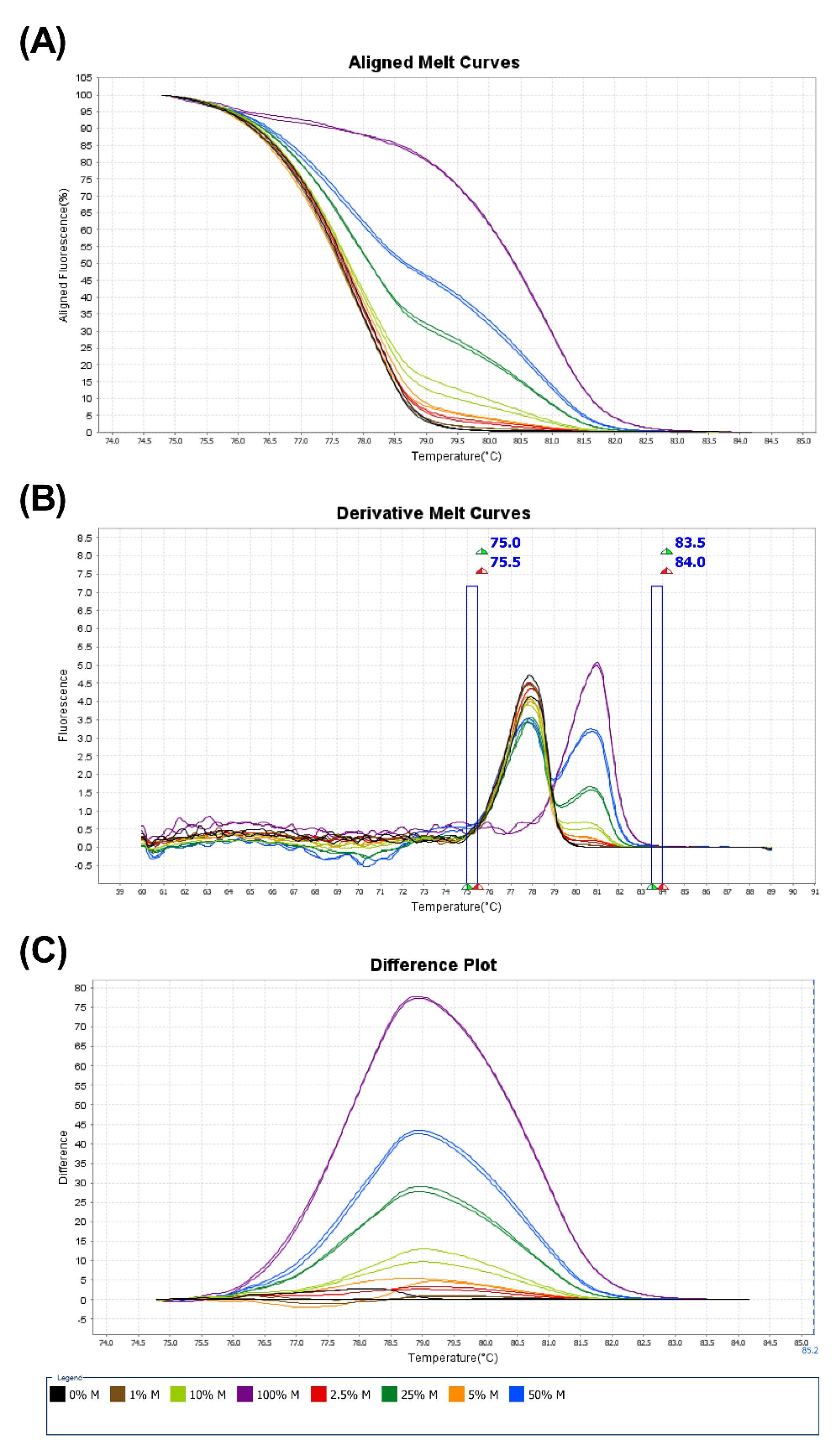

With bisulfite-converted DNA, MS-HRM was performed on the CpG Island within the promoter region of OGG1. The Applied Biosystems High-Resolution Melt Software (Applied Biosystems Cat. No. A30150, USA) was used for analyzing HRM data due to its high sensitivity and accuracy. In addition, the accuracy of the MS-HRM is dependent upon the successful performance of methylation control tests. Sections A, B, and C of Fig. 3, respectively, show the aligned Melt Curve, the derivative Melt Curve, and the difference plot of methylation control tests with different percentages of methylated and unmethylated bisulfite-converted DNA.

Fig. 3.

The accuracy of methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting (MS-HRM) test. Graphs A represent Aligned Melt Curve Plot, Graphs B represent Derivative Melt Curve Plot and Graphs C represent difference plot of 0% (black), 1% (brown), 2.5% (red), 5% (orange), 10% (light green), 25% (dark green), 50% (blue), and 100% (purple) methylated controls associated with the OGG1. The plot of each DNA methylated control is defined in a specific color with descriptions in the legends section.

.

The accuracy of methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting (MS-HRM) test. Graphs A represent Aligned Melt Curve Plot, Graphs B represent Derivative Melt Curve Plot and Graphs C represent difference plot of 0% (black), 1% (brown), 2.5% (red), 5% (orange), 10% (light green), 25% (dark green), 50% (blue), and 100% (purple) methylated controls associated with the OGG1. The plot of each DNA methylated control is defined in a specific color with descriptions in the legends section.

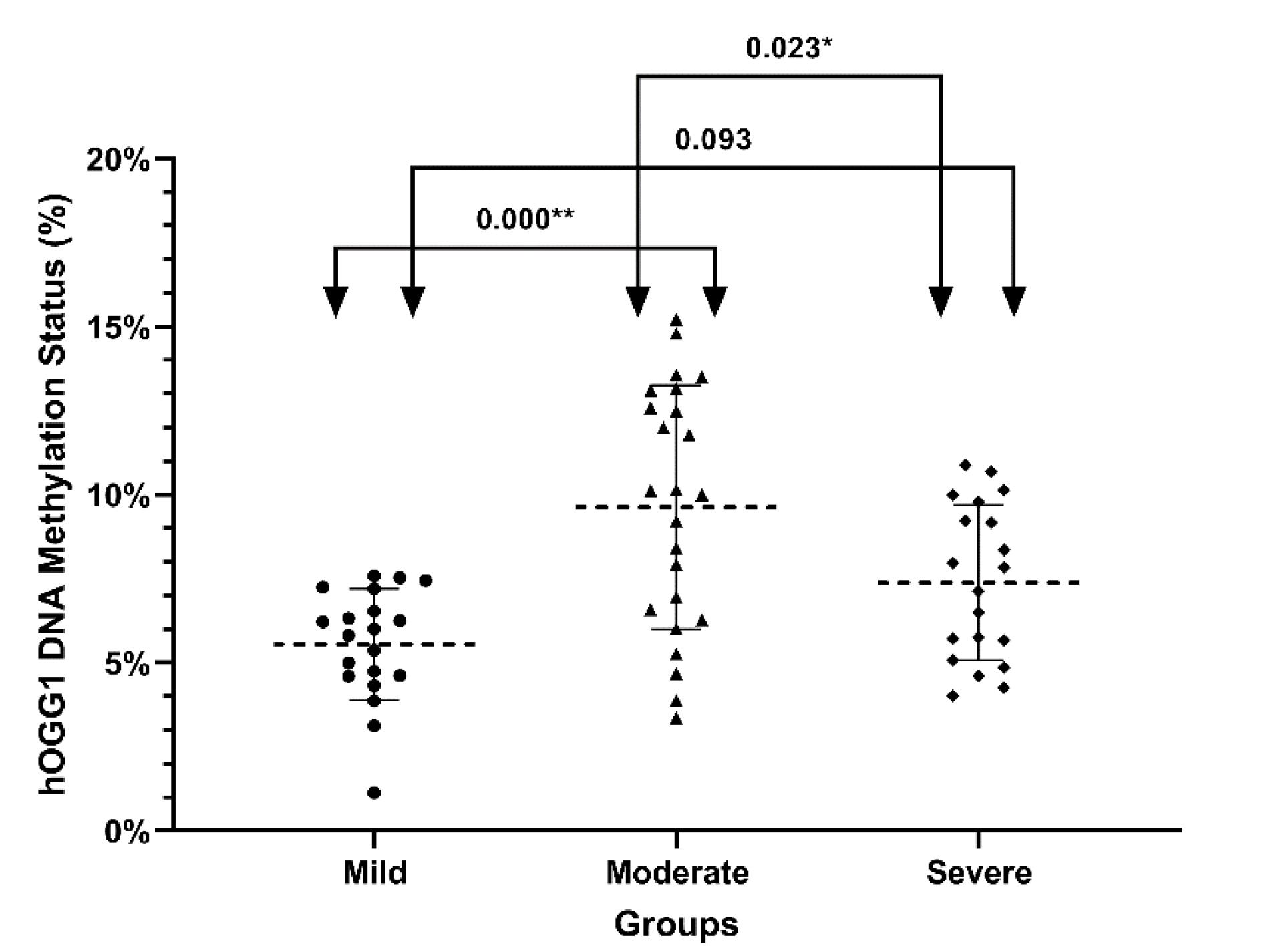

One-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in OGG1 DNA methylation status (P < 0.0001). According to the multiple comparison analysis conducted using Tukey's post hoc test, the mild vs moderate and moderate vs severe groups were significantly different (P < 0.001 and P = 0.023, respectively). In Fig. 4, we present the mean and standard deviation of DNA methylation status for each of the groups based on a dot plot.

Fig. 4.

DNA methylation status of OGG1 in SM-exposed patients with different pulmonary complications. In mild (n = 20), moderate (n = 24), and severe (n = 20) groups of participants exposed to SM, the percentage of DNA methylation in the promoter of OGG1 is shown as a dot plot (mean and standard deviation). The percentage of DNA methylation was evaluated using methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test shows a significant difference. Arrows and numbers indicate the P-values between groups.

.

DNA methylation status of OGG1 in SM-exposed patients with different pulmonary complications. In mild (n = 20), moderate (n = 24), and severe (n = 20) groups of participants exposed to SM, the percentage of DNA methylation in the promoter of OGG1 is shown as a dot plot (mean and standard deviation). The percentage of DNA methylation was evaluated using methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test shows a significant difference. Arrows and numbers indicate the P-values between groups.

DNA methylation and mRNA expression of OGG1 did not appear to be correlated

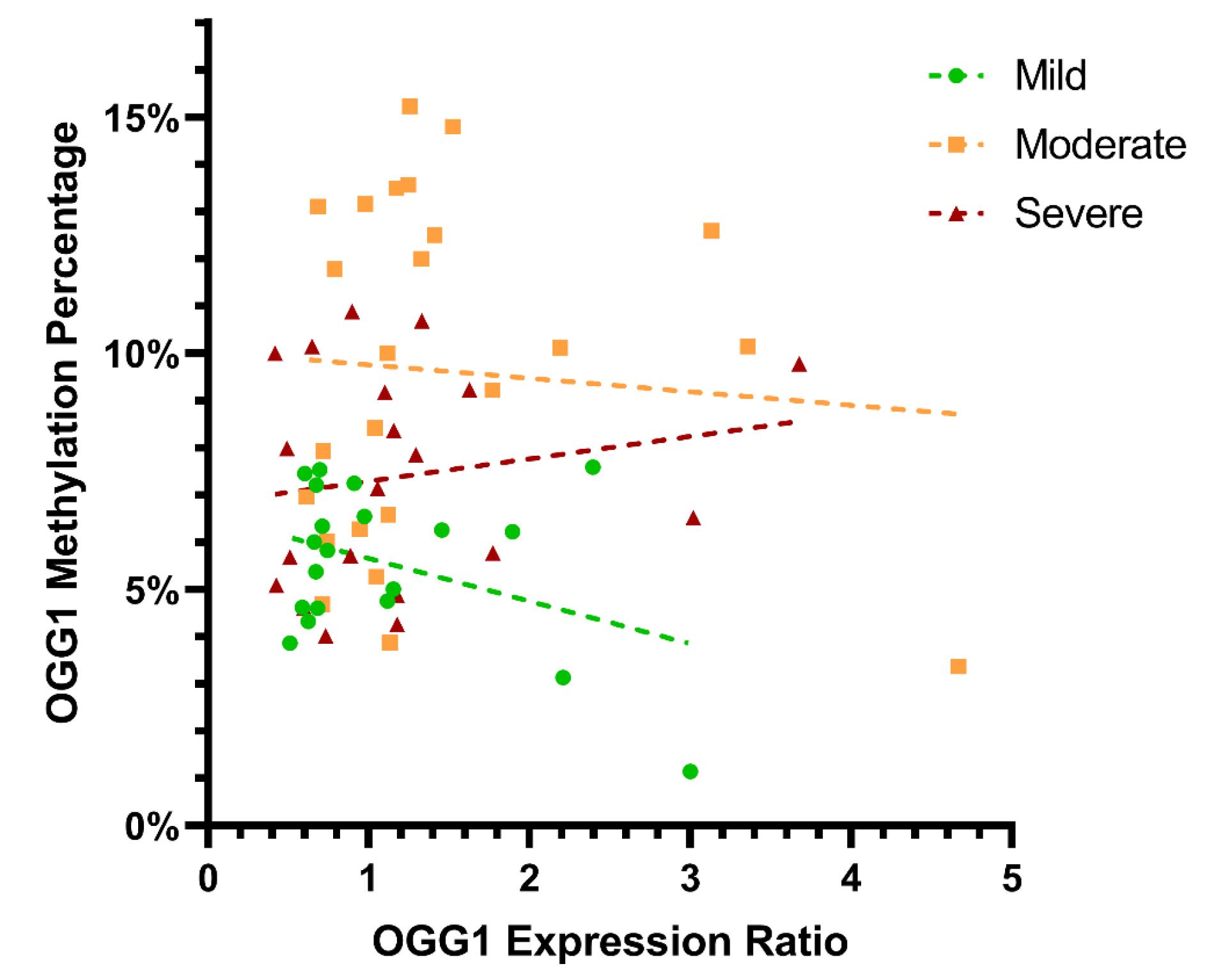

In order to examine the association between DNA methylation and mRNA expression, we computed Spearman's correlation coefficient (r) within each group and among all participants (Fig. 5). We did not find a significant correlation between OGG1 DNA methylation and mRNA expression in the mild, moderate, and severe groups and across all subjects (P = 0.856, 0.238, 0.539, 0.087, respectively). The results of further investigation, among other variables, revealed a positive association between OGG1 mRNA expression and aging (P = 0.012).

Fig. 5.

The relationship between DNA methylation gene expression of OGG1 in SM-exposed patients with pulmonary complications. The scatter plot demonstrating Spearman's correlation between OGG1 DNA methylation status and mRNA expression ratios within SM exposed patients with mild moderate and severe pulmonary complications. DNA methylation status and the mRNA expression ratio of OGG1 were not significantly correlated in the mild, moderate, or severe groups or across all subjects (p = 0.856, 0.238, 0.539, 0.087, respectively).

.

The relationship between DNA methylation gene expression of OGG1 in SM-exposed patients with pulmonary complications. The scatter plot demonstrating Spearman's correlation between OGG1 DNA methylation status and mRNA expression ratios within SM exposed patients with mild moderate and severe pulmonary complications. DNA methylation status and the mRNA expression ratio of OGG1 were not significantly correlated in the mild, moderate, or severe groups or across all subjects (p = 0.856, 0.238, 0.539, 0.087, respectively).

Discussion

SM with the lipophilic feature has a long-lasting devastating effect on all living beings, including humans. Various tissues of the human body, especially the respiratory system, are suffering long-standing from the cytotoxic activity of SM. Oxidative stress is one of the consequences of the cytotoxic activity of SM, causing DNA damage and the formation of an inappropriate 8-Oxoguanine base.6 Hence, the cells confront this DNA damage induced by SM through the BER repair pathway.

The present study evaluated the mRNA expression and promoter CpG island DNA methylation of the main BER repair protein known as 8-Oxoguanine DNA Glycosylase1 (OGG1) in the blood samples of individuals exposed to SM 27 years ago. Sixty-four male individuals were involved in this study and classified into mild, moderate, and severe groups based on pulmonary problems. Also, we showed the correlation between OGG1 mRNA expression and promoter CpG island DNA methylation.

Our result indicated significantly OGG1 mRNA overexpression in moderated groups compared to mid groups (P = 0.036), and DNA methylation alterations were significantly different in mild-moderate and moderate-severe groups (P = 0.000 and 0.023, respectively). Despite the lack of correlation between OGG1 DNA methylation and mRNA expression, aging was associated with OGG1 mRNA expression levels.

Dysregulation of OGG1 expression has been observed in numerous human diseases, especially cancer. Biopsies of colorectal cancer patients examined by immunohistochemistry exhibit elevated OGG1 expression compared to normal colonic mucosa.20 While Sakata et al, using the same technique, indicated an association between downregulation of OGG1 expression and tumor depth T4, venous invasion, and lymphatic vessel invasion in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.21 also, Karihtala et al demonstrated an association between a lack of OGG1 expression and aggressive breast cancer.22 These mentioned studies indicated that the Dysregulation of OGG1 is related to the stage and severity of the diseases and can be tissue-dependent. As a result, it could be suggested that OGG1 mRNA expression increases in the early phases of the disease but decreases in the late stages, suggesting other molecular mechanisms may be recruited by cells at that point in time. These studies can be consistent with our results that indicated OGG1 upregulation in the moderate group and downregulation in the severe group. Also, the closest study related to this work was conducted by Behboudi et al., which showed mRNA overexpression of OGG1 in Mild/Moderate and Severe/Very severe lung complications of SM-exposed patients 20 years ago compared to Unexposed controls using real-time PCR.15 The result revealed although there was a significant difference between OGG1 mRNA expression in the SM-exposed patients versus Unexposed controls, but there was no significant difference between mild/moderate and severe/very severe lung complications of SM-exposed patients. Compared to our study that the mild and moderate groups were analyzed independently, while in Behboudi et al. study, mild and moderate groups were analyzed cooperatively versus the severe and very severe groups. We hypothesize that the difference in results is mainly due to the fact that this study was conducted on subjects who had been exposed to SM 27 years ago and had a different cohort of participants.

DNA methylation modifications play a critical role in gene expression regulation as an epigenetic mechanism that is dynamic and environment-dependent over the lifetime of individuals. So far, not many studies have investigated the methylation status of the OGG1 promoter. One of the proteins involved in DNA demethylation and interacting with OGG1 is the Ten-eleven translocation (Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3) proteins.23 In a study by Wang et al on the effect of arsenic on human bronchial epithelial cells (HBE), It was shown that arsenic induced oxidative stress, inhibited Tet proteins, and maintained promoter methylation in OGG1.24 Another study consistent with our study examining the effects of PAH (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) exposure on OGG1 DNA methylation on venous blood in Chinese coke workers, found that workers exposed to high levels of PAHs had hypermethylation on the promoter of OGG1 compared to workers exposed to low levels of PAHs. In addition, the study showed that OGG1 DNA methylation is positively associated with urinary 1-OHP (an indicator of PAH exposure in the urine) and negatively associated with G0/G1 phase arrest, whereas in the present study, no correlations were noted between OGG1 DNA methylation and other variables.25

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is unquestionable that genetic and epigenetic alteration plays a significant role in the wide variety of long-term complications experienced by people exposed to SM. In spite of this, the relationship between genetic and epigenetic changes has not been adequately explored. As a result of our study, we found significant differences in OGG1 mRNA expression levels as well as DNA methylation between groups of lung complication people exposed to SM. However, we found no correlation between these factors. These studies contribute not only to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of SM but may also assist in finding therapeutic interventions. It is recommended that future studies should investigate other genes involved in DNA repair pathways using high-throughput techniques. Additionally, since the expression of genes varies in different tissues, it is proposed to investigate genetic and epigenetic changes in other tissues, including the lungs, eyes, and skin.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

√ Upon binding to macromolecules, sulfur mustard disrupts many vital functions of cells and causes oxidative stress

√ Except in the short term, sulfur mustard also affects cells in the long run

What is new here?

√ Long-term exposure to sulfur mustard alters the mRNA expression and DNA methylation of OGG1

√ The changes in the mRNA expression of OGG1 cannot be attributed to DNA methylation

Acknowledgments

The study would not have been possible without all of the patients who participated.

Competing Interests

The authors report there are no conflict of interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data were generated at the Immunoregulation Research Center at Shahed University. Derived data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research according to the ethics code IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1398.005.

References

- Balali-Mood M, Mousavi S, Balali-Mood B. Chronic health effects of sulphur mustard exposure with special reference to Iranian veterans. Emerg Health Threats J 2008; 1:e7. doi: 10.3134/ehtj.08.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Deans AJ, West SC. DNA interstrand crosslink repair and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2011; 11:467-80. doi: 10.1038/nrc3088 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shakarjian MP, Heck DE, Gray JP, Sinko PJ, Gordon MK, Casillas RP. Mechanisms mediating the vesicant actions of sulfur mustard after cutaneous exposure. Toxicol Sci 2010; 114:5-19. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp253 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Powell KL, Thames HD, MacLeod MC. Detoxication of sulfur half-mustards by nucleophilic scavengers: robust activity of thiopurines. Chem Res Toxicol 2010; 23:488-96. doi: 10.1021/tx900190j [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kehe K, Schrettl V, Thiermann H, Steinritz D. Modified immunoslotblot assay to detect hemi and sulfur mustard DNA adducts. Chem Biol Interact 2013; 206:523-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2013.08.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Laskin JD, Black AT, Jan YH, Sinko PJ, Heindel ND, Sunil V. Oxidants and antioxidants in sulfur mustard-induced injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1203:92-100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05605.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- David SS, O'Shea VL, Kundu S. Base-excision repair of oxidative DNA damage. Nature 2007; 447:941-50. doi: 10.1038/nature05978 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Panahi Y, Fattahi A, Nejabati HR, Abroon S, Latifi Z, Akbarzadeh A. DNA repair mechanisms in response to genotoxicity of warfare agent sulfur mustard. Environ ToxicolPharmacol 2018; 58:230-6. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2018.01.012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fu D, Calvo JA, Samson LD. Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12:104-20. doi: 10.1038/nrc3185 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Salimi S, Noorbakhsh F, Faghihzadeh S, Ghaffarpour S, Ghazanfari T. Expression of miR-15b-5p, miR-21-5p, and SMAD7 in Lung Tissue of Sulfur Mustard-exposed Individuals with Long-term Pulmonary Complications. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2019; 18:332-9. doi: 10.18502/ijaai.v18i3.1126 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ghaffarpour S, Ghazanfari T, Ardestani SK, Pourfarzam S, Fallahi F, Shams J. Correlation between MMP-9 and MMP-9/TIMPs complex with pulmonary function in sulfur mustard exposed civilians: Sardasht-Iran cohort study. Arch Iran Med 2017; 20:74-82. [ Google Scholar]

- Vafa A, Faghihzadeh S, Ghafarpour S, Behboodi H, Zamani MS, Ghazanfari T. Methylation of IFN-I³ in sulfur mustard-exposed patients. Daneshvar Medicine 2020; 27:17-24. [ Google Scholar]

- Ghazanfari T, Faghihzadeh S, Aragizadeh H, Soroush MR, Yaraee R, Mohammad Hassan Z. Sardasht-Iran cohort study of chemical warfare victims: design and methods. Arch Iran Med 2009; 12:5-14. [ Google Scholar]

- Khateri S, Ghanei M, Keshavarz S, Soroush M, Haines D. Incidence of lung, eye, and skin lesions as late complications in 34,000 Iranians with wartime exposure to mustard agent. J Occup Environ Med 2003; 45:1136-43. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000094993.20914.d1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Behboudi H, Noureini SK, Ghazanfari T, Ardestani SK. DNA damage and telomere length shortening in the peripheral blood leukocytes of 20years SM-exposed veterans. Int Immunopharmacol 2018; 61:37-44. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.05.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eghtedardoost M, Hassan ZM, Askari N, Sadeghipour A, Naghizadeh MM, Ghafarpour S. The delayed effect of mustard gas on housekeeping gene expression in lung biopsy of chemical injuries. BiochemBiophys Rep 2017; 11:27-32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2017.04.012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wojdacz TK, Dobrovic A, Hansen LL. Methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting. Nat Protoc 2008; 3:1903-8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.191 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bakshi C, Vijayvergiya R, Dhawan V. Aberrant DNA methylation of M1-macrophage genes in coronary artery disease. Sci Rep 2019; 9:1429. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38040-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 2001; 29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- PM DEA, Dorg L, Pham S, Andersen SN. DNA Repair Protein Expression and Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress in Ulcerative Colitis and Sporadic Colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res 2021; 41:3261-70. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15112 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sakata K, Yoshizumi T, Izumi T, Shimokawa M, Itoh S, Ikegami T. The Role of DNA Repair Glycosylase OGG1 in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Anticancer Res 2019; 39:3241-8. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13465 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Karihtala P, Kauppila S, Puistola U, Jukkola-Vuorinen A. Absence of the DNA repair enzyme human 8-oxoguanine glycosylase is associated with an aggressive breast cancer phenotype. Br J Cancer 2012; 106:344-7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.518 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Zhuang Z, Wang W, He L, Wu H, Cao Y. OGG1 is essential in oxidative stress induced DNA demethylation. Cellular signalling 2016; 28:1163-71. [ Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Wang W, Zhang A. TET-mediated DNA demethylation plays an important role in arsenic-induced HBE cells oxidative stress via regulating promoter methylation of OGG1 and GSTP1. Toxicol In Vitro 2021; 72:105075. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2020.105075 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Niu Y, Pan B, Liu Y, Zhang B, Li X. OGG1 methylation mediated the effects of cell cycle and oxidative DNA damage related to PAHs exposure in Chinese coke oven workers. Chemosphere 2019; 224:48-57. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.02.114 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]