BioImpacts. 7(4):219-226.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2017.26

Original Research

Effect of hydroxychloroquine on oxidative/nitrosative status and angiogenesis in endothelial cells under high glucose condition

Aysa Rezabakhsh 1, 2, Soheila Montazersaheb 2, 3, Elahe Nabat 2, Mehdi Hassanpour 4, Azadeh Montaseri 5, Hassan Malekinejad 6, 7, Ali Akbar Movassaghpour 8, Reza Rahbarghazi 2, 9, *, Alireza Garjani 1, 2, *

Author information:

1Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2Stem Cell Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3Department of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4Depatment of Clinical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

5Department of Anatomical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

6Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran

7Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran

8Hematology and Oncology Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

9Department of Applied Cell Sciences, Faculty of Advanced Medical Sciences, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

Under the diabetic condition, sustained production of oxidative/nitrosative stress results in irreversible vascular injuries. A great number of diabetic pathologies, such as inefficient or aberrant neo-angiogenesis emerge following chronic hyperglycemic condition. Lack of enough data exists regarding hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) contribution on angiogenesis during diabetes mellitus.

Methods:

To better address whether HCQ could blunt or exacerbate oxidative status and angiogenesis under high glucose condition (HCG), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were exposed to 30 µM HCQ in combination with 30 mM glucose over a course of 72 hours. Viability was measured was evaluated by MTT assay. We used Griess method and TBARS assay to monitor changes in the levels of NO and MDA followed by flow cytometric analysis of ROS using DCFDA. To show the impact of HCQ on cell motility and in vitro angiogenic properties, we exploited routine scratch test and in vitro tubulogenesis, respectively.

Results:

Our data showed that HCQ diminished cell viability under 5 and 30 mM glucose contents. HCQ significantly decreased the total levels of nitric oxide (NO), malondialdehyde (MDA), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in both sets of environments. Additionally, inhibitory effects were observed on cell migration after exposure to HCQ (P < 0.001). Anti-angiogenic activity of HCQ was confirmed by the reduction of tube areas under a normal or surplus amount of glucose (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

In overall, results suggest that HCQ changes the oxidative/nitrosative status of HUVECs both in 5 and 30 mM conditions. HCQ is able to reduce migration and angiogenic activity of HUVECs irrespective of the glucose content.

Keywords: High glucose condition, Hydroxychloroquine, Endothelial cells, Oxidative stress, Tubulogenesis

Copyright and License Information

© 2017 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Up to the present, diabetes mellitus correlates with the prominent hallmark of chronic hyperglycemia. A plethora of experiments unveiled a growing number of newly diagnosed cases of diabetic subjects annually, which endure diabetes-associated pathologies – in particular – vascular malfunction.

1

To address the underlying mechanism of diabetes pathophysiology, endothelial cells, the main cell type that furnishing luminal surface of vessels, are extensively being examined during diabetic changes.

2

Corroborating to literature, an inevitable correlation between high glucose condition (HGC) and occurrence of vasculopathy, either micro- or macro-, has been elucidated so far.

3

Additionally, prolonged exposure of endothelial cells to HGC raises hemostasis disturbances or cell biochemical abnormalities, which is originated by the wide variety of normal or abnormal byproduct compounds.

4

Considering this statement, oxidative status during high blood sugar is touted as one of the main issues of current studies correlated with diabetes mellitus.

5

Diabetes is usually accompanied by impaired antioxidant defenses or increased generation of free radicals, resulting in the hallmark of oxidative stress-related complications.

6

It is thought that reactive oxygen species (ROS) exert a crucial effect during intracellular oxidative stress.

7

The subsequent rise in ROS contents yields a detrimental outcome on lipid membranes integrity, cell function and the dynamics of nucleic acids and enzymes.

8

An enhanced degradation of intracellular signaling pathways by ROS is thought to be the fundamental mechanism hindering nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability during cardiovascular disease.

9

An impairing NO bioavailability is possibly intensified with peroxynitrite formation, named as nitrosative deleterious effects.

10

Consistent with numerous experimental studies, different byproducts could also exacerbate this condition. For instance, there are studies reporting that elevated levels of plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) contribute to increasing the markers of oxidative status during diabetes.

11

Regardless the biochemical alteration, hyperglycemia impairs cell migration, endothelial angiogenic capacity, and extracellular matrix remodeling.

12

Therefore, in diabetic patients deficient wound healing is very frequent.

3

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), a potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drug, derived from chloroquine is extensively administrated to alleviate various diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, malaria, and etc.

14,15

This lysosomotropic agent accumulates in some acidic organelles, in particular lysosomes, yielding in the elevation of concentrations up to 1000-fold more than detected in in vitro condition. By increasing intralysosomal pH from 4 to 6, the proteolytic activity of different enzymes is then neutralized.

5

Additionally, the higher pH within lysosomes brings an arrangement of macromolecules inside endosomes, and even modifies protein encoding in the Golgi apparatus, which results in an inhibitory effect on intracellular processing such as autophagy, glycosylation, and secretion of numerous proteins.

16

With these assumptions, HCQ is simultaneously administrated with convenient anti-cancer regimens to promote the effectiveness of the therapy by enhancing tumor cells killing.

17

A recent intracellular mechanism has been recently discovered HCQ inhibited toll-like receptor 9 (TLR-9). The TLRs are distributed on the cell surface and act as receptors for microbial agents, promoting inflammatory responses by engaging the activation of the innate immune system of each cell.

18

It is well-established that the blocking of TLRs and adjacent effectors reduce ROS generation.

19

Also, the HCQ administration blunt risk of incident diabetes mellitus with advantages on lipids contents and glycemic indexes in autoimmune diseases.

20,21

It seems that HCQ could modulate angiogenic mechanisms by the action evoked via immune cells and/or endothelial lineage.

22

Nevertheless, migratory behavior and pro-/anti-angiogenic effects of HCQ under HGC and diabetic subjects remain to be elucidated.

The current experiment was taken up to address whether HCQ, could attenuate or worsen adverse effects of HGC on endothelial cell lineage derived from human umbilical vein (HUVECs), over a period of 72 hours. Therefore, the modulatory effects of HCQ on oxidative/nitrosative status, migration and tubulogenesis of 30 mM-treated cells were investigated in in vitro condition. It seems that the results of the current experiment could help in better understanding of the possible effect of HCQ on vascular diabetic complications.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

For cell culture, we used Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12, Biowest), fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Gibco. MTT powder, Penicillin-Streptomycin and trypsin-EDTA solution were purchased from ATOCEL (Budapest, Hungary). 2'-7-dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) and D-glucose were ordered from Sigma-Aldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany). HCQ was prepared from Zahravi Pharmaceutical Company (Tehran, Iran). Protein lysis buffer, RIPA, was obtained from Santa Cruz (California, USA). Matrigel was purchased from BD Biosciences (California, USA).

Cell culture and treatment protocols

We obtained HUVECs from the National Cell bank (Pasteur Institute, Iran). HUVECs were cultured in DMEM/F12, enriched with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Next, HUVECs were transferred to a humidified atmosphere with 7% CO2 at 37°C and detached after reaching to 80% confluency exposed to 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution. Cells after third passage were submitted to the present study. To mimic normal and HGCs, the HUVECs were re-suspended in 0.5% FBS-supplemented DMEM/F12 medium with 5 mM and 30 mM D-glucose, respectively. To prepare, drug stock solution, HCQ dissolved in distilled water freshly.

Cell viability

Time-course determination of effect of HCQ on HUVECs viability

In this experiment, to explore the effect of HCQ on HUVECs viability 30 µM of this drug was used. Briefly, 1.5 × 104 cells were transferred onto each well of 96-well plates and exposed to the pre-determined concentration of HCQ, either condition with normal and/or 30 mM glucose content, for three culture time-points, including 24, 48 and 72 hours. Ultimately, the cell viability rates of exposed HUVECs were determined by MTT assay. Finally, optical density was read at 570 nm by a microplate reader (BioTek). The rate of viable cell survival was expressed as a percentage relative to the non-treated HUVECs. We monitored any morphological change and vacuolating effect under experimental procedure during the incubation period.

Assessment of oxidative/nitrosative stress status

NO measurement

The production of NO, under experimental condition through different culture time, was determined by the colorimetric quantification of accumulated nitrite/nitrate levels in the supernatant (nM) using Griess reagent. By using this reagent, NO is converted into nitrite. In an acidic condition, nitrite produces nitrous acid. Following exposure to sulfanilamide, nitrous acid forms a diazonium salt and in the presence of N- (1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine·2HCL generates an azo dye. Briefly, 1 × 104 cells/well was plated in 96-well plates. After treatment procedure at 24, 48 and 72 hours, 200 µL of the supernatant of each sample was incubated 10 minutes with 20 µL of Griess A and then incubated 2 minutes with 20 µL of Griess B reagents and further analyzed by microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek, USA). The NO level was presented as nmol and sodium nitrite used to draw standard curve.

23

Lipid peroxidation determination

The amount of lipid peroxidation was detected by measuring MDA byproduct based on thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) generation. First, 1 × 106 cells/well was expanded in 6-well plates. After 24 hours, cells treated by HCQ in media which containing a different concentration of glucose (5 mM and 30 mM) for 24, 48 and 72 hours. After experimental procedure, cells (1 × 106 HUVECs/well) were seeded in 6-well plates, cellular protein was obtained by RIPA lysis buffer kit. Total proteins in the media were measured using Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific NanoDropTM 1000). A total of 500 µL of the protein lysates were then mixed with 3 mL of 1% phosphoric acid and 1 mL of 0.7% thiobarbituric acid solutions. The samples were incubated in boiling water for 45 minutes after cooling of samples, they were centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 minutes and optical density determined at 532. Finally, the amount of MDA was shown as per mg of total extracted protein.

Intracellular ROS modulation

To understand the contributory effect of HCQ on the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), we performed a flow cytometric analysis in cells co-exposed to glucose (5 and 30 mM) with or without HCQ, plated in 48-well plates for 72 hours. HUVECs were detached and collected by enzymatic method. Here, we incubated cells with 10 µM DCFDA for 30 minutes at RT. The percent of ROS positive cells was measured by BD FACSCalibur system and analyzed by FlowJo version 7.6.1.

Scratch assay

For this propose, HUVECs were plated onto 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) and allowed to reach one-cell-thick monolayers. Thereafter, HUVECs were exposed to 30 mM of glucose as a negative control and HCQ at 5 and 30 mM glucose concentration. Thereafter, scratches were created by using yellow pipette tip. The wells were washed twice with PBS. We recorded time-lapse images in four different points, including 0, 24, 48 and 72 hours after treatment and the distances of scratch edges (µm) were scored by AxioVision software.

In vitro tubulogenesis

In vitro capillary-like formation was done in accordance with our previous work with some modifications.

24

After 72-hour incubation of HUVECs with pre-determined doses of HCQ administered under normal and HGCs, the tubulogenesis capacity of HUVECs were determined by Matrigel substrate. We transferred 100 µL of Matrigel into each well of 48-well plate and maintained 1 hour at 37°C to be solidified. Thereafter, 500 µL medium containing 5 × 104 cells/well of control and treated HUVECs were added to Matrigel layer. After 24 hours, 3 high power fields were visualized. The area of tubes was calculated by AxioVision software (Version Rel 4.8).

Statistical analysis

Data on current experiment are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were evaluated using the GraphPad InStat software version 2.02 (GraphPad Software Inc.). The data analyses between groups were carried out via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test. Given results at different times were compared mean difference was significant at P<0.05. In histograms, the statistical difference between the groups presented by brackets with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Results

HCQ diminished cell viability rate under HGC

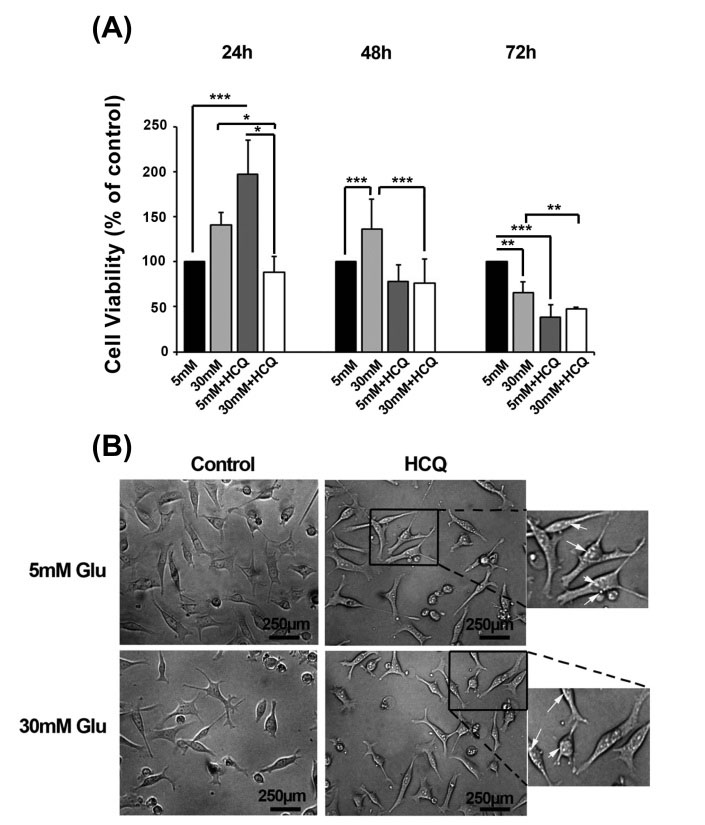

Based on data obtained from MTT assay, the cell viability rate was increased in 30 mM-treated cells as compared to relative 5 mM control group during first 48 hours (P < 0.001) while a decline in cells proliferation rate coincided with an induced cytotoxic effect at 72 hours (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1A). At first 24 hours, we found a significant increase in cell survival after exposed to a combined regime of HCQ and 5 mM glucose as compared to the cells treated with HCQ under 30 mM glucose and related control (5 mM glucose alone) (P < 0.05). Meanwhile, cell survival rate was diminished profoundly in HCQ group under 5 mM glucose during 48 and 72 hours compared with 5 mM glucose control group especially at 72 hours (P<0.001). Moreover, HCQ potentially yielded a low rate of cell viability under high glucose concentration (30mM) during different time points compared with parallel control (30mM glucose alone) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). The treatment of HUVECs with HCQ and 5 mM or 30 mM glucose yielded a striking accumulation of intracytoplasmic vacuoles only during the first 24 hours (Fig. 1B). Notably, the accumulated vacuoles subsequently disappeared after 24 hours under HCQ treatment in which we could not detect the vacuoles at 48 and 72 hours (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

The cell viability percentage was analyzed in 30 µM hydroxychloroquine-treated cells in the conditions with 5 and 30 mM glucose for 72 hours (n = 5) (A). Microphotograph of cells under experimental procedure showed an increase in the number of intracytoplasmic vacuoles either in normal or high contents of glucose after 24 hours (B). Student's t test was used for two matched groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ).

.

The cell viability percentage was analyzed in 30 µM hydroxychloroquine-treated cells in the conditions with 5 and 30 mM glucose for 72 hours (n = 5) (A). Microphotograph of cells under experimental procedure showed an increase in the number of intracytoplasmic vacuoles either in normal or high contents of glucose after 24 hours (B). Student's t test was used for two matched groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ).

HCQ could mitigate oxidative/nitrosative stress status in HUVECs under HGC

A great body of evidence has been reported the modulatory impact of HCQ, on oxidative stress in the different situation.

25

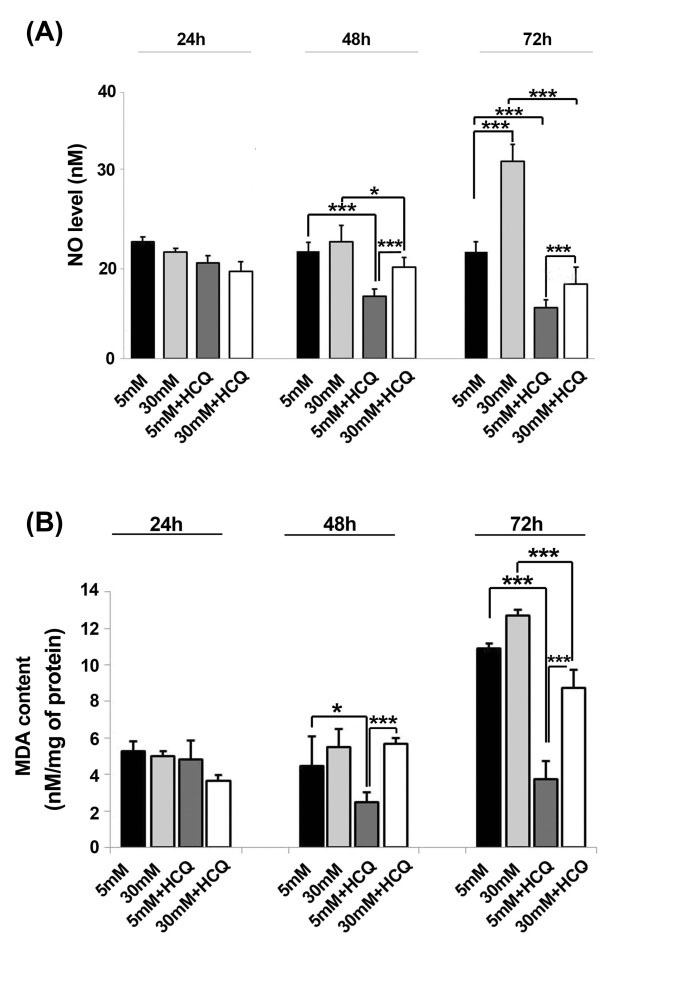

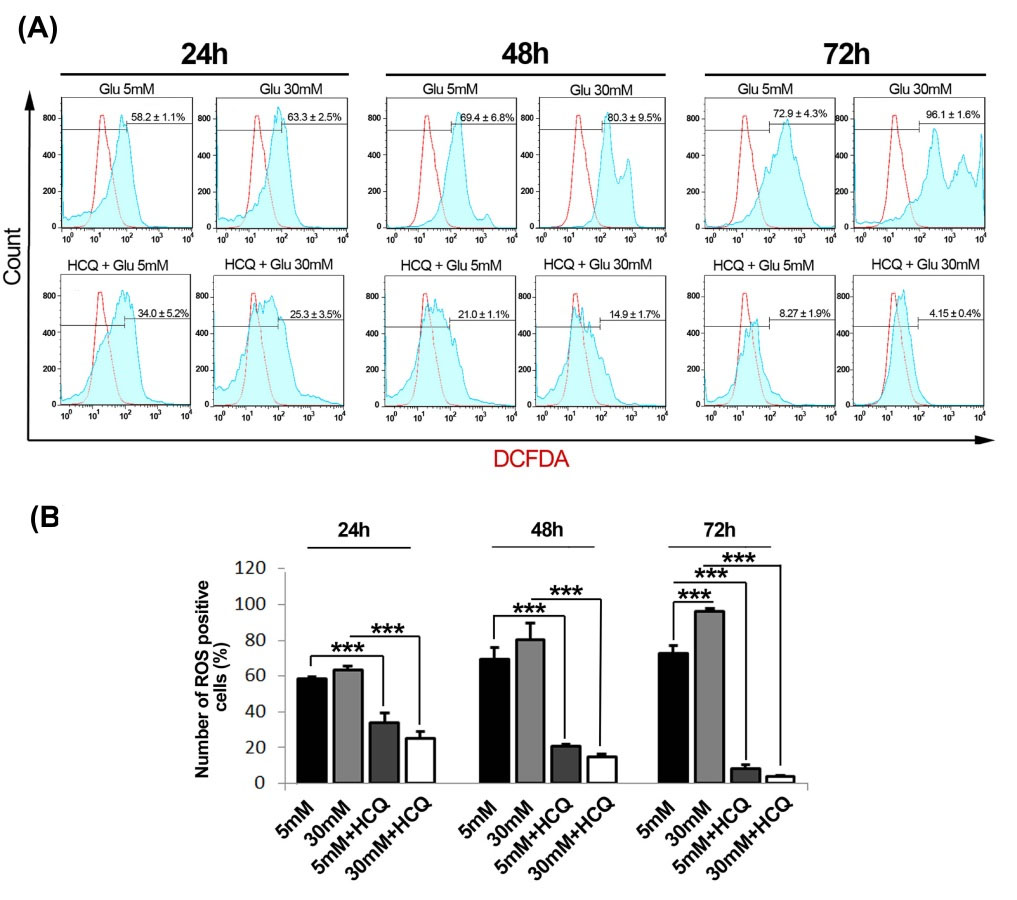

Our results showed in vitro incubation of HUVECs with 30 mM glucose caused an increased in the amount of NO especially at 72 h (P < 0.001) while a significant NO reduction was documented in cells after exposure to HCQ at 48 and 72 hours as compared to related controls (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the intracellular content of MDA increased both in normal and hyper glucose conditions in the absence of HCQ at 72 hours (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, we also showed that the addition of HCQ could return MDA levels below the range of time-matched control groups either in 5 mM or 30 mM conditions after 72- hour culture, although an upward trend of total MDA increment was obtained through time (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). It seems that high glucose condition administration of endothelial lineage cells tailored oxidative stress status resistance. As such the flow cytometric monitoring of intracellular ROS levels further notified a burst of glucose-induced response in a time-dependent manner under HGC. It is also worthy to note HCQ exert superior significant effects to lessen the total amount of cell ROS contents in all conditions. Strictly, the generated levels of ROS diminished in all treated groups of HCQ in both conditions at the end stage of the current experiment (Fig. 3A-B).

Fig. 2.

Time trend change of NO and MDA contents in HUVECs treated with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and 5 or 30 mM glucose (A & B) One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test *P<0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n=5) (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ).

.

Time trend change of NO and MDA contents in HUVECs treated with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and 5 or 30 mM glucose (A & B) One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test *P<0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n=5) (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ).

Fig. 3.

The analysis of ROS content by flow cytometry following treatment with hydroxychloroquine under a condition of 5 and 30 mM glucose during 24, 48 and 72 hours (n=3) (A and B). Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test) (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ).

.

The analysis of ROS content by flow cytometry following treatment with hydroxychloroquine under a condition of 5 and 30 mM glucose during 24, 48 and 72 hours (n=3) (A and B). Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test) (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ).

Endothelial cells migration capacity changed by HCQ

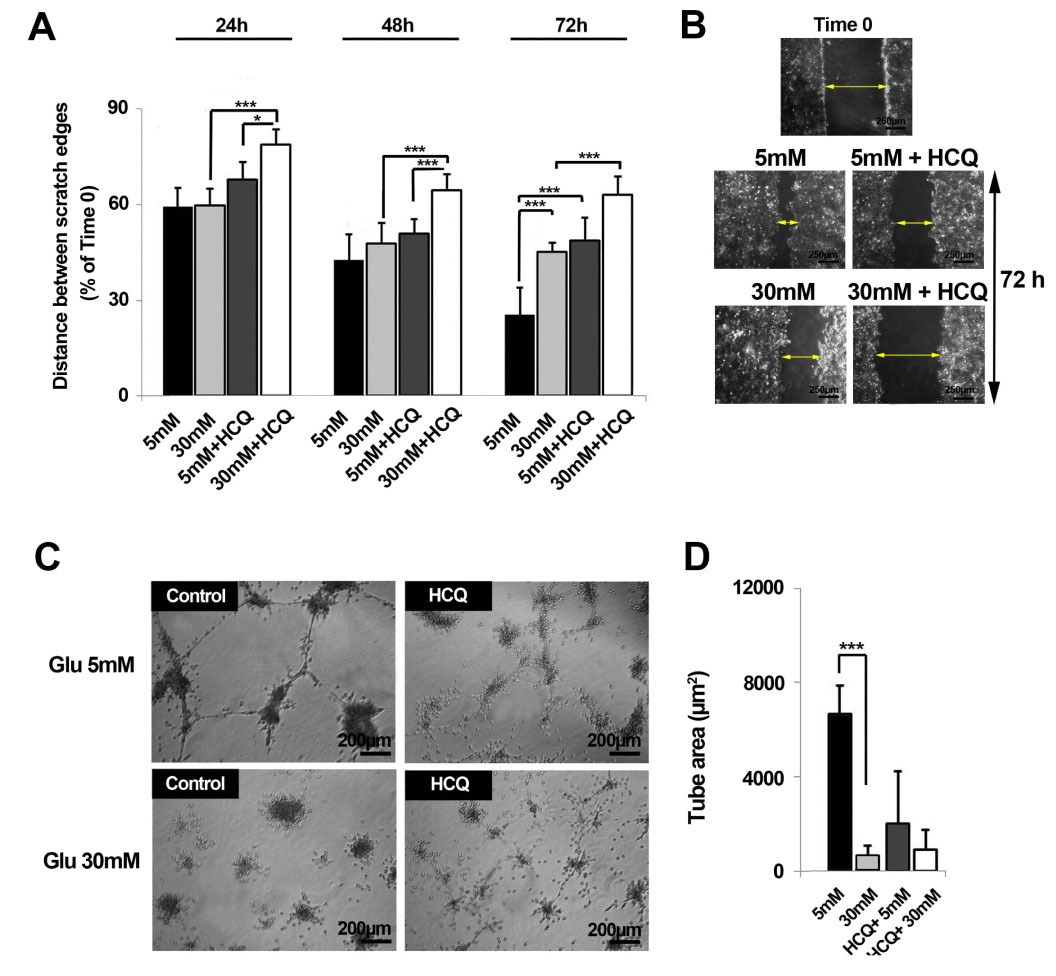

Based on the obtained data, naive cells under treatment with 5 mM glucose showed an appropriate migration through the end-stage of the experiment as compared to HGC (30 mM glucose) after 72 hours. Notably, the wound healing rate was highly suppressed in HUVECs exposed to 30 mM glucose (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A-B). Interestingly, cells being exposed to HCQ lost their migration properties either in 5 mM or 30 mM glucose condition as compared to matched control groups (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A-B).

Fig. 4.

The effect of hydroxychloroquine on HUVECs migration rate over the course of 72 h. It was determined that hydroxychloroquine possessed the capacity to induce cell migration exposed to 5 and 30 mM glucose (n=3) (A & B). The cells being exposed to hydroxychloroquine lost in vitro tube formation properties (C & D) (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ). Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test) (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ).

.

The effect of hydroxychloroquine on HUVECs migration rate over the course of 72 h. It was determined that hydroxychloroquine possessed the capacity to induce cell migration exposed to 5 and 30 mM glucose (n=3) (A & B). The cells being exposed to hydroxychloroquine lost in vitro tube formation properties (C & D) (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ). Results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test) (hydroxychloroquine = HCQ).

Angiogenic response of HUVECs was inhibited by HCQ under HGC

Regarding the main aspect of angiogenesis involving in the re-arrangement and localization of endothelial cells into a 3D tubule-like structure, the incubation of endothelial cells with 30 mM glucose completely abolished in vitro tubulogenesis activity as compared with normal glucose primed cells over course of 72 hours (P < 0.001). Notably, an extensively anti-angiogenic activity of ECs observed in normal condition, albeit no significant changes was here reported in between 2 conditions and parallel control (Fig. 4C-D). In addition, the treatment of endothelial cells with HCQ in both conditions potentially impeded the formation of 3D tube structures (Pcontrol versus HCQ 5mM and 30 mM <0.001).

Discussion

This experiment exhibited herein is the first to assay the effect of HCQ on 30 mM-treated HUVECs after 72 hours. Therefore, deleterious/beneficial effects of HCQ on cell viability, oxidative/nitrosative status, migration capacity and in vitro tubulogenesis were investigated. First, we showed that HCQ attributed a significant dropping in HUVECs viability in conditions with normal and high glucose contents. Based on previously published data, HCQ -induced apoptosis of HUVECs through a lysosomal pathway and accumulation.

26

The intracytoplasmic accumulated lysosomes are prone to release different enzymes such as cathepsin B and to augment mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, resulting in Bax activity.

27

The reduction in survivin level and an increase of Caspase 3 activity promote apoptotic-induced cell death during exposure to HCQ.

28

It has also been proven an autophagic cell death of HCQ is induced by blocking the autophagosome fusion and the accumulation of aberrantly metabolized products,

29

suggesting HCQ -primed cancer cells could be sensitized to anti-cancer agents.

30

In human dermal fibroblasts, the modulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 phosphorylation after treatment with HCQ suppresses metabolic activity and cell proliferation.

29

As a consequence, the application of HCQ could favor anti-proliferative effects on different tumors in a patient. In diabetic subjects, chronic oxidative stress may be correlated with the dynamics of excess substrates available such as carbohydrates and lipids exist during hyperglycemic changes.

31

In this regard, there is a growing body of evidence implicating overproduction of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in metabolic abnormalities of diabetes.

32

Both ROS and RNS cause damage to proteins, carbohydrates, lipids and nucleic acids, resulting in oxidative/nitrosative stress.

33

In mitochondria, oxidative/nitrosative stress lead to declined mitochondrial ATP synthesis, uncontrolled opening of the mitochondrial membrane pore (MPTP), altered calcium homeostasis among other deleterious events for cell survival.

28

Cosenzi and et al showed that oxidative/nitrosative stress was stimulated at initial times after streptozotocin administration in diabetic rats.

34

In spite of subtractive cell viability rates recorded by the application HCQ, our data showed the alleviation in the oxidative status by a reduction in total levels of MDA, NO, and ROS. It seems an intricate network of signaling pathways reported to be involved in NO production.

35-37

Irrespective of an inevitable role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis iNOS expression, several studies showed HCQ blunted the generation of NO by eliminating 20S proteasomal activation and reduction of interferon-β in macrophages and chondrocytes.

38

In accordance with our data, Gómez-Guzmán et al acclaimed that chronic using of HCQ could protect kidney and improve endothelial cell dysfunction by decreasing ROS level in autoimmune disease.

39

Consistent with the present study, an enhanced reduction of oxidative markers could be related to HCQ anti-inflammatory effects.

40,41

Therefore, one could hypothesize that this agent is able to clinically reduce the hyperglycemia-related oxidative/nitrosative stress injury in diabetic patients.

It is believed that oxidative stress induced by high glucose contents disturbed migratory property.

28

This inhibition may result from aberrant cell polarity, a decrease of adhesion maturation and protrusion destabilization.

33

In the current study, neither migratory nor tubulogenesis behavior of HCQ-exposed HUVECs was discovered under normal or HGC. To the best of our knowledge, there are a wide gap and limited data regarding the prohibitory effect of HCQ on cell mobilization mechanisms so far. Recently, it has been confirmed that HCQ has reduced the affinity of chemokine CXCL12 to its receptor CXCR4 resulting in CXCL12-induced cell migration in a pancreatic cancer model.

42

CXCR4 is touted to possess a crucial impact in the development of pancreatic cancer.

28

HCQ has the ability to block CXCL12-CXCR4 axis by engaging the ERK pathway controlling apoptosis and cell growth.

28

Additionally, a decline in tip cell population, typified by CD34, could be deduced as another prominent anti-angiogenic activity of HCQ.

28

In some diabetes-induced pathology, the uncontrolled proliferation and impaired angiogenesis are responsible for clinical complications. Regarding dual effects and context-dependent of angiogenic responses during diabetes mellitus, such as seen in foot ulcers or diabetic retinopathy, the modulation and orchestration of vascularization switch off/on must be precisely considered.

43-45

Therefore, it is reasonable that HCQ could presumably be used as angiogenesis modulator during hyperglycemic condition.

46

Conclusion

In summary, this study focused on HCQ effects on HUVECs in terms of oxidative status, migration property and in vitro capillary-like formation in a set of normal and HGC. It seems that both oxidative and nitrosative stress mechanisms could participate in endothelial cells aberrant functions subjected to HGC.

Competing interests

No potential conflicts of interest declared.

Ethical approval

There is nothing to be declared.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Vice Chancellor for Research of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

simple

-

√ HCQ is currently used for the therapy of malaria and some

cancers.

-

√ Oxidative/nitrosative stress and aberrant angiogenic

behavior have been documented for endothelial cells when

exposed to 30 mM glucose.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ HCQ decreased endothelial cell viability under HGC.

-

√ No obvious angiogenic switch response was evident in the

combination of HCQ and 30 mM glucose.

-

√ The migration of endothelial cells was diminished by HCQ

under the treatment of 30 mM glucose.

-

√ HCQ is able to blunt oxidative/nitrosative stress of

endothelial cells in the presence of 30 mM glucose.

References

- Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, Jia W, Ji L, Xiao J. Prevalence of Diabetes among Men and Women in China. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1090-101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908292 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nachman RL, Jaffe EA. Endothelial cell culture:beginnings of modern vascular biology. J Clin Invest 2004; 114:1037-40. doi: 10.1172/JCI23284 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Du X, Matsumura T, Edelstein D, Rossetti L, Zsengellér Z, Szabó C, Brownlee M. Inhibition of GAPDH activity by poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase activates three major pathways of hyperglycemic damage in endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 2003; 112:1049-57. doi: 10.1172/JCI18127 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Popov D. Endothelial cell dysfunction in hyperglycemia:Phenotypic change, intracellular signaling modification, ultrastructural alteration, and potential clinical outcomes. Int J Diabetes Mellit 2010; 2:189-95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdm.2010.09.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tangvarasittichai S. Oxidative stress, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes 2015; 6:456-80. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i3.456 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Giacco F, Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res 2010; 107:1058-70. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.110.223545 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mittal M, Siddiqui MR, Tran K, Reddy SP, Malik AB. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014; 20:1126-67. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5149 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lü JM, Lin PH, Yao Q, Chen C. Chemical and molecular mechanisms of antioxidants:experimental approaches and model systems. J Cell Mol Med 2010; 14:840-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00897.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Behrendt D, Ganz P. Endothelial function:from vascular biology to clinical applications. Am J Cardiol 2002; 90:40-48. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02963 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Zou M-H. Molecular insights and therapeutic targets for diabetic endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2009; 120:1266-86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.835223 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti G, Ceolin RB, Valcorte T, De Bona KS, de Lucca L, Gonçalves TL, Moretto MB. δ-Aminolevulinate dehydratase activity in type 2 diabetic patients and its association with lipid profile and oxidative stress. Clin Biochem 2011; 44:1105-109. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.06.980 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Tan SH, Nicolas V, Bauvy C, Yang ND, Zhang J. Activation of lysosomal function in the course of autophagy via mTORC1 suppression and autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Cell Res 2013; 23:508-23. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.11 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Braiman-Wiksman L, Solomonik I, Spira R, Tennenbaum T. Novel insights into wound healing sequence of events. Toxicol Pathol 2007; 35:767-79. doi: 10.1080/01926230701584189 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yang ZJ, Chee CE, Huang S, Sinicrope FA. The role of autophagy in cancer:therapeutic implications. Mol Cancer Ther 2011; 10:1533-541. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0047 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kalia S, Dutz JP. New concepts in antimalarial use and mode of action in dermatology. Dermatol Ther 2007; 20:160-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00131.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fox RI. Mechanism of action of hydroxychloroquine as an antirheumatic drug. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1993; 23:82-91. doi: 10.1016/S0049-0172(10)80012-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rangwala R, Leone R, Chang YC, Fecher LA, Schuchter LM, Kramer A. Phase I trial of hydroxychloroquine with dose-intense temozolomide in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy 2014; 10:1369-79. doi: 10.4161/auto.29118 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 2003; 21:335-76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yuan X, Zhou Y, Wang W, Li J, Xie G, Zhao Y. Activation of TLR4 signaling promotes gastric cancer progression by inducing mitochondrial ROS production. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4:e794. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.334 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen YM, Lin CH, Lan TH, Chen HH, Chang SN, Chen YH. Hydroxychloroquine reduces risk of incident diabetes mellitus in lupus patients in a dose-dependent manner:a population-based cohort study. Rheumatology 2015; 54:1244-49. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu451 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bili A, Sartorius JA, Kirchner HL, Morris SJ, Ledwich LJ, Antohe JL.

Hydroxychloroquine use and decreased risk of diabetes

in rheumatoid arthritis patients

. J Clin Rheumatol 2011; 17:115-20. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318214b6b5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A, Rockfield S, Taran N, Haller E, Engelman RW, Flores I. Effect of hydroxychloroquine and characterization of autophagy in a mouse model of endometriosis. Cell Death Dis 2016; 7:e2059. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.361 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Malekinejad H, Rezabakhsh A, Rahmani F, Hobbenaghi R. Silymarin regulates the cytochrome P450 3A2 and glutathione peroxides in the liver of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Phytomedicine 2012; 19:583-90. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.02.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi E, Nassiri SM, Rahbarghazi R, Siavashi V,

Araghi

A

Araghi

A

.

Endothelial juxtaposition of distinct adult stem cells activates

angiogenesis signaling molecules in endothelial cells

.

Cell Tissue

Res

2015; 362:597-609. doi: 10.1007/s00441-015-2228-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Virdis A, Tani C, Duranti E, Vagnani S, Carli L, Kühl AA. Early treatment with hydroxychloroquine prevents the development of endothelial dysfunction in a murine model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17:277. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0790-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen H-H, Zhou H-J, Wang W-Q, Wu G-D. Antimalarial dihydroartemisinin also inhibits angiogenesis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2004; 53:423-32. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0751-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Boya P, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Poncet D, Andreau K, Vieira HL, Roumier T. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization is a critical step of lysosome-initiated apoptosis induced by hydroxychloroquine. Oncogene 2003; 22:3927-36. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206622 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Aziz AK, Shouman S, El-Demerdash E, Elgendy M, Abdel-Naim AB. Chloroquine synergizes sunitinib cytotoxicity via modulating autophagic, apoptotic and angiogenic machineries. Chem Biol Interact 2014; 217:28-40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.04.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ramser B, Kokot A, Metze D, Weiß N, Luger TA, Böhm M. Hydroxychloroquine modulates metabolic activity and proliferation and induces autophagic cell death of human dermal fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129:2419-26. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.80 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Manic G, Obrist F, Kroemer G, Vitale I, Galluzzi L. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for cancer therapy. Mol Cell Oncol 2014; 1:e29911. doi: 10.4161/mco.29911 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Son SM. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in pathogenesis of vascular complications of diabetes. Diabetes Metab J 2012; 36:190-8. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2012.36.3.190 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Albert CR, Schlesinger WJ, Viall CA, Mulla MJ, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, Abrahams VM.

Effect of Hydroxychloroquine on

Antiphospholipid Antibody‐Induced Changes in First Trimester

Trophoblast Function

. Am J Reprod Immunol 2014; 71:154-64. doi: 10.1111/aji.12184 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lamers ML, Almeida ME, Vicente-Manzanares M, Horwitz AF, Santos MF. High glucose-mediated oxidative stress impairs cell migration. PloS One 2011; 6:e22865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022865 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Trachtman H, Futterweit S, Pine E, Mann J, Valderrama E. Chronic diabetic nephropathy:role of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Pediatr Nephrol 2002; 17:20-9. doi: 10.1007/s004670200004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Skrivanova E, Van Immerseel F, Hovorkova P, Kokoska L. In Vitro selective growth-inhibitory effect of 8-hydroxyquinoline on clostridium perfringens versus bifidobacteria in a medium containing chicken ileal digesta. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0167638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167638 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vuolteenaho K, Kujala P, Moilanen T, Moilanen E. Aurothiomalate and hydroxychloroquine inhibit nitric oxide production in chondrocytes and in human osteoarthritic cartilage. Scand J Rheumatol 2005; 4:475-9. doi: 10.1080/03009740510026797 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vuolteenaho K, Kujala P, Moilanen T, Moilanen E. Aurothiomalate and hydroxychloroquine inhibit nitric oxide production in chondrocytes and in human osteoarthritic cartilage. Scand J Rheumatol 2005; 34:475-9. doi: 10.1080/03009740510026797 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tzeng SF, Huang HY, Lee TI, Jwo JK.

Inhibition of

lipopolysaccharide‐induced microglial activation by preexposure

to neurotrophin‐3

. J Neurosci Res 2005; 81:666-76. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20586 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Guzmán M, Jiménez R, Romero M, Sánchez M, Zarzuelo MJ, Gómez-Morales M. Chronic hydroxychloroquine improves endothelial dysfunction and protects kidney in a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Hypertension 2014; 64:330-37. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.114.03587 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Sun F, Wang J, Mao X, Xie L, Yang SH. mTOR signaling inhibition modulates macrophage/microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and secondary injury via regulatory T cells after focal ischemia. J Immunol 2014; 192:6009-19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303492 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hage MP, Al-Badri MR, Azar ST.

A favorable effect of

hydroxychloroquine on glucose and lipid metabolism beyond its

anti-inflammatory role

. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2014; 5:77-85. doi: 10.1177/2042018814547204 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Yip ML, Shen X, Li H, Hsin LY, Labarge S. Identification of anti-malarial compounds as novel antagonists to chemokine receptor CXCR4 in pancreatic cancer cells. PloS One 2012; 7:e31004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Zhang T, Gong C, Sheng Y, Lu B, Zhou L. Erianin inhibits high glucose-induced retinal angiogenesis via blocking ERK1/2-regulated HIF-1α-VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway. Sci Rep 2016; 6:34306. doi: 10.1038/srep34306 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Lv L. Effect of local insulin injection on wound vascularization in patients with diabetic foot ulcer. Exp Ther Med 2016; 11:397-402. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2917 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rezabakhsh A, Nabat E, Yousefi M, Montazersaheb S, Cheraghi O, Mehdizadeh A. Endothelial cells' biophysical, biochemical, and chromosomal aberrancies in high‐glucose condition within the diabetic range. Cell Biochem Funct 2017; 35:83-97. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3251 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rahman R, Murthi P, Singh H, Gurusinghe S, Mockler JC, Lim R. The effects of hydroxychloroquine on endothelial dysfunction. Pregnancy Hypertens 2016; 6:259-62. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2016.09.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]