Bioimpacts. 7(3):167-175.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2017.20

Original Research

Thermoresponsive graphene oxide – starch micro/nanohydrogel composite as biocompatible drug delivery system

Mina Sattari 1, †, Marziyeh Fathi 1, †, Mansour Daei 2, Hamid Erfan-Niya 2, *, Jaleh Barar 1  , Ali Akbar Entezami 3

, Ali Akbar Entezami 3

Author information:

1Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2Department of Chemical and Petroleum Engineering, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

3Laboratory of Polymer Chemistry, Faculty of Chemistry, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

Stimuli-responsive hydrogels, which indicate a significant response to the environmental change (e.g., pH, temperature, light, …), have potential applications for tissue engineering, drug delivery systems, cell therapy, artificial muscles, biosensors, etc. Among the temperature-responsive materials, poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm) based hydrogels have been widely developed and their properties can be easily tailored by manipulating the properties of the hydrogel and the composite material. Graphene oxide (GO), as a multifunctional and biocompatible nanosheet, can efficiently improve the mechanical strength and response rate of PNIPAAm-based hydrogels. Here, hydrogel composites (HCs) of PNIPAAm with GO was developed using the modified starch as a biodegradable cross-linker.

Methods:

Micro/nanohydrogel composites were synthesized by free radical polymerization of NIPAAm in the suspension of different feed ratio of GO using maleate-modified starch (St-MA) as cross-linker and Tetrakis (hydroxymethyl) phosphonium chloride (THPC) as a strong oxygen scavenger. The HCs were characterized by FT-IR, DSC, TGA, SEM, and DLS. Also, the phase transition, swelling/deswelling behavior, hemocompatibility and biocompatibility of the synthesized HCs were investigated.

Results:

The thermal stability, phase transition temperature and internal network crosslinking of HCs increases with increasing of the GO feed ratio. Also, the swelling/deswelling, hemolysis, and MTT assays studies confirmed that the HCs are a fast response, hemocompatible and biocompatible materials.

Conclusion:

The employed facile approach for the synthesis of HCs yields an intelligent material with great potential for biomedical applications.

Keywords: Biocompatible, Hemolysis, Hydrogel composite, Swelling/deswelling, Thermoresponsive

Copyright and License Information

© 2017 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Pharmaceutical nanotechnology is interested in formulation of therapeutics agents with desired nanoplatforms such as nanoparticles, micelles, nanocapsules, hydrogels and nanoconjugates.

1

Recently, innovative vectors as sustained drug delivery systems (DDSs), have been attracted the most attention for disease treatment.

2

Hydrogels as hydrophilic and three dimensional polymeric networks offer widespread application in drug delivery, tissue engineering, cell therapy and regenerative medicine.

3-6

The affinity of hydrogels for water absorbing is due to the existence of hydrophilic functional groups (e.g., –OH, –CONH–, –CONH2, and –SO3H) in their structures.

4

The biodegradable hydrogels have been developed as novel DDSs; because they are biocompatible and could be conjugated to specific factors.

7,8

Thermo-responsive hydrogels are approximately the most investigated responsive hydrogel systems due to their unique characteristics for controlled DDSs.

9

Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm) as a widely used thermo-sensitive hydrogel, shows a reversible phase transition temperature around 32°C which is around the body temperature.

10

However, the slow response of conventional PNIPAAm gels, as well as low mechanical strength and biocompatibility, restrict their applications.

11,12

Decreasing the size of hydrogels to nanohydrogels can be considered the effective route to gain hydrogels with fast response manner. Utilizing the chemical crosslinking agents is necessary for the synthesis of hydrogels. However, these agents are toxic materials which must be eliminated from their structure before they can be utilized.

13

Hence, the hydrogels of PNIPAAm have been modified to be more applicable materials via consolidating other appropriate materials to improve mechanical properties, biocompatibility and nontoxicity.

14

Polysaccharides as components of biodegradable and biocompatible DDSs have been received considerable attention; because they can be produced through well-defined and reproducible method from the natural sources.

15-18

Graphene, as an emerging 2D nanocarbon material, has specific optical, thermal, electronic and mechanical properties which make it suitable for diverse applications (e.g., nanoelectronic devices, nanocomposites, and sensors).

19

Graphene oxide (GO) is a graphene with various carboxylic, epoxy and hydroxyl groups, which has high surface activity and processability for covalent and non-covalent conjugations.

20-22

The functionalized GO with various biocompatible polymers (e.g., polyethylene glycol, poly(vinyl alcohol), PNIPAAm, and chitosan) has many applications such as decoration of DNA, wound healing, gene delivery, bioimaging, tissue engineering, photothermal therapy and delivery of tumor drugs.

23-26

The GO/PNIPAAm interpenetrating (IPN) hydrogel has been previously produced via covalent cross-linking of GO sheets with PNIPAAm copolymer in water by the reaction between epichlorohydrin (ECH) and carboxylic groups as dual thermo- and pH-sensitive IPN hydrogel.

27

Here, a new approach is developed for the synthesis of thermoresponsive GO hydrogel composites (HCs) using free radical polymerization of the NIPAAm in the matrix of GO/modified starch with different feed ratios. The modified starch is used as non-toxic cross-linker and oxygen scavenger is applied to increase the efficacy of the polymerization. The physico-chemical properties, swelling/deswelling behavior, hemo- and in vitro biocompatibilities are investigated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Graphite powder, cornstarch, maleic anhydride (MA) and tetrakis (hydroxymethyl) phosphonium chloride were supplied from Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA). N-Isopropylacrylamide (NIPAAm) was used as received by Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ). Other materials and solvents with analytical grade were utilized as received.

Synthesis of modified starch by maleic anhydride

Maleate-modified starch (St-MA) was synthesized by esterification of hydroxyl groups of starch with MA in a similar method as described previously.

28

Therefore, corn starch (8 g) was added into 50 mL deionized water and stirred. Then, 25 mL of NaOH solution (2.0 M) was added. After complete dissolution, it was changed to a yellowish solution and then, MA (7.4 g) was added. The obtained mixture was stirred at 100°C within 4 hours. After that, the mixture was cooled down to room temperature, and soluble products were precipitated by ethanol. The precipitation was obtained by filtration, and washed (3×) with ethanol to eliminate the unreacted MA and finally, was dried at 60°C in a vacuum oven to get St-MA. After modification, St-MA could be dissolved simply in water.

Oxidation of graphite by modified Hummer method

GO was synthesized from natural graphite via modified Hummers' method.

28

Briefly, the mixture of 240 mL of H2SO4 and 26.7 mL of H3PO4 were stirred in an ice bath. Then, natural graphite (2 g) was added to the mixture and stirred while KMnO4 (12 g) was slowly added. The temperature was adjusted at 50°C in oil bath and stirred within 12 hours at this temperature. In this step, the mixture color changed from black to gray. After that, the solution was cooled down to room temperature and diluted with distilled water (250 mL) and then 5 mL of hydrogen peroxide (30 wt%) was added. The mixture was filtered and washed with HCl aqueous solution and subsequently with distilled water until the suspension reached to neutral pH. Finally, the suspension was vacuum dried at 60°C for 12 h hours to obtain GO powder.

Synthesis of thermoresponsive PNIPAAm/St-MA/GO HC

HCs of PNIPAAm/St-MA/GO were synthesized by the free radical polymerization at high temperatures. The designated amount of GO was dispersed in distilled water (8 mL) with blending by ultrasonic waves for 60 minutes. The required amounts of NIPAAm and St-MA were added to the GO suspension. The mixture was blended for 60 minutes under argon gas and heated to achieve 60°C. Then, 0.5 mL of THPC as oxygen scavenger was added to the flask to remove oxygen in the balloon. At this stage, hydrogen peroxide, as an initiator, was added to initiate the polymerization reaction under argon gas at 60°C for 6 hours and subsequently, cooled down to room temperature and then washed with distilled water to eliminate the unreacted monomers. The as-prepared HCs were dried in a vacuum oven at 50°C. To evaluate the impact of GO on the properties of the synthesized HCs, the different feed ratios of GO was examined which is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The feed composition ratios of the synthesized hydrogel composites

|

HCs

|

NIPAAm (mg)

|

St-MA (mg)

|

Oxygen scavenger (mL)

|

H

2

O

2

(mL)

|

GO (mg)

|

GO ( wt%)

|

| HC1 |

0.675 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.0270 |

3.36 |

| HC2 |

0.675 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.0337 |

4.16 |

| HC3 |

0.675 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.0504 |

6.1 |

Characterization by FT-IR

The FT-IR spectra of GO, St-MA and HCs were recorded on a Tensor 27 spectrometer (Bruker Optik GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany) at room temperature using KBr pellets.

1H NMR spectroscopy

The 1H NMR spectrum was recorded at 25°C by 400 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker Optik GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany). The sample was dissolved in D2O.

Scanning electron microscope

Scanning electron micrographs were taken by LEO 1430 VP SEM (Carl Zeiss, Germany). To keep the pores of HCs intact for imaging, the HC samples were left in liquid nitrogen and then were broken. To record the micrographs, the samples of equal thickness were gold-coated.

Differential scanning calorimetry

The differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) estimations were derived using a Linseis DSC-PT10 (Germany) instrument. DSC measurements were performed to obtain information about the glass transition temperature. The samples were weighed (5-10 mg) and scanned between 10°C and 240°C, by the heating rate of 20°C/min and cooling rate of 10°C/min, under nitrogen gas.

Dynamic light scattering measurement

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to define the particle size distribution of the prepared HCs in an aqueous medium. For measurement, HCs (1 mg/mL) were swelled and then were sonicated for 3 minutes. The DLS measurements were done at 25°C by using a DLS instrument, Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK) equipped with an argon laser operating at 632.8 nm at 90°.

The LCST determination of HCs

The lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of HCs were determined by UV-visible spectrophotometer, Agilent Cary-100 UV-Vis (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at wavelength 541 nm in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with pH = 7.4. The samples of HCs, with a concentration of 1 mg/mL, were well dispersed by sonication before the measurement. The temperature of the solution was set from 25 to 50°C and sample cell was thermostated in a water bath at different temperatures prior to the measurements. The LCST of the HCs was determined when optical absorbance increased around 50% of initial absorbance.

29

Thermal gravimetric analysis

Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) of dried hydrogel samples was done using LINSEIS L81A1750 (Germany) with the heating rate of 10°C /min from 25°C to 700°C under a nitrogen flow.

Swelling/deswelling kinetics

The swelling measurement of HCs was performed gravimetrically. Therefore, the pre-weighted HCs were submerged in distilled water at room temperature. The excess surface water was removed by filter paper, and the weight of the swollen sample was measured at different time periods. The swelling ratio (SR %) of HCs was obtained via the following equation:

where Ws indicates the weight of the swollen HCs at a predetermined time, and Wd shows the dried weight of samples. The deswelling kinetics of the HCs was accompanied gravimetrically using the weight measurement of water in HCs at specific time intervals (Wt) after the swollen hydrogel at 6°C was rapidly transferred to the water at 45°C. The water retention (WR) was calculated by the following equation:

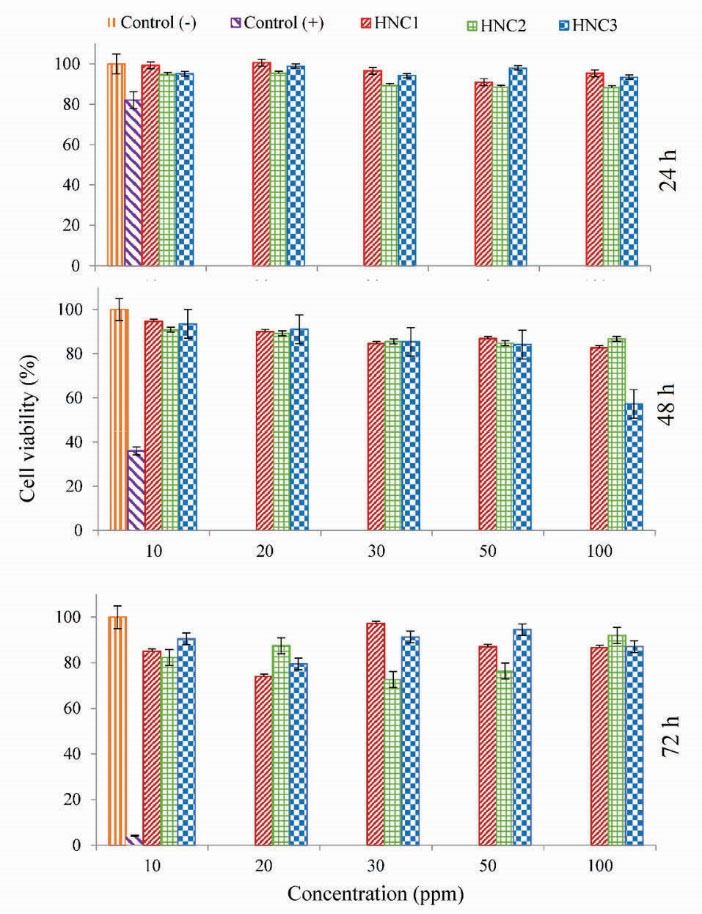

In vitro cytotoxicity study

In vitro cytotoxicity of the HCs was evaluated by the MTT assay. In summary, A549 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate in RPMI 1640 medium. After the incubation for overnight, cells were treated with HCs at different concentrations (10, 20, 30, 50 and 100 ppm) for 24, 48 and 72 hours. At designated time points, the media were removed and 50 μL MTT solution (2 mg/mL) plus 150 μL of media were added to each well. The cell viability was measured by reading the absorbance of each well at 570 nm by using a microplate reader (Elx808, Biotek, USA) after 5 minutes of shaking. The cell viability was calculated by reading the absorbance for the treated cells as compared to the un-treated control cells.

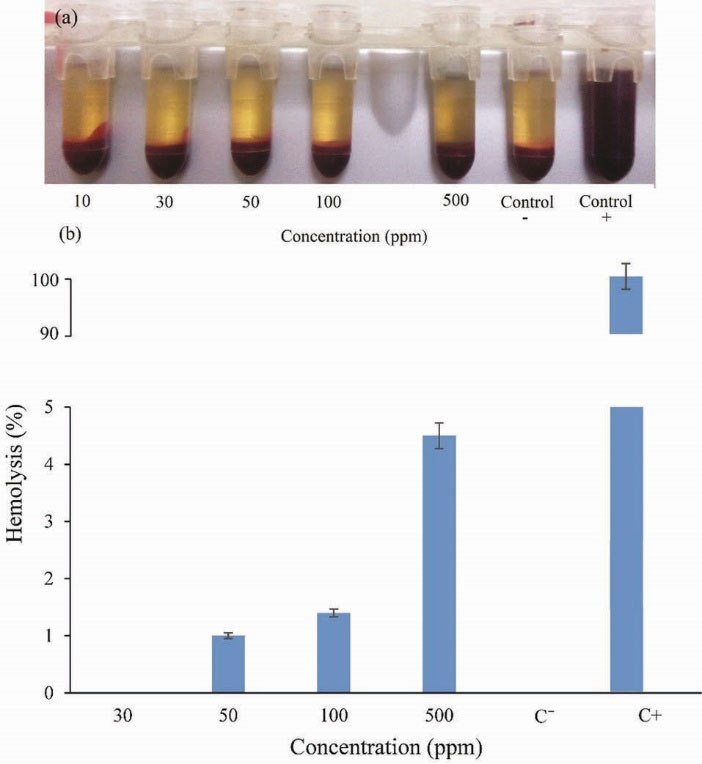

Hemolysis assay

Hemolysis assay was performed by fresh human blood. The solutions of HCs with different concentrations (10, 30, 50, 100 and 500 ppm) were prepared in PBS (pH = 7.4). Then, 750 μL blood was added to 750 μL sample solutions, and the resulting mixtures were incubated for 3 hours at 37°C in an incubator. After centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 15 minutes, the absorbance of the supernatant was measured by UV–vis at 541 nm. The PBS and distilled water was used as negative and positive control, respectively.

30

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as the mean vales ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed using Student’s t test. Values of P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

FT-IR Spectra

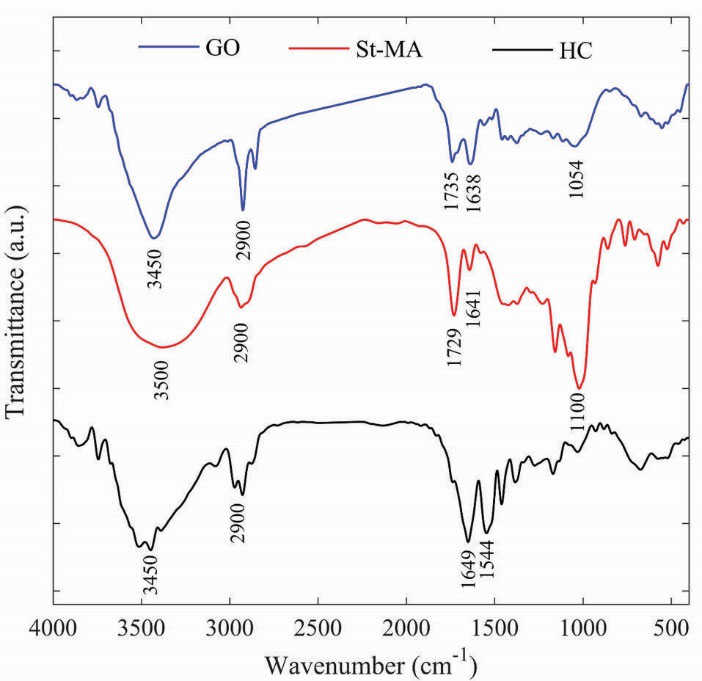

The FT-IR spectroscopy analysis was performed to evaluate the structure and functional groups of the GO, St-MA and HCs to indicate the existence of characteristic functional groups of each component as shown in Fig. 1. The GO sheet showed apparent adsorption peaks for the carboxyl C=O (1735 cm−1), aromatic C=C (1638 cm−1), epoxy C–O (1237 cm−1), alkoxy C–O (1054 cm−1), and hydroxyl –OH (3430 cm−1) groups. The presentation of functional groups including oxygen, such as C=O and C–O, confirmed that the graphite is oxidized into GO and it is according to literature.

26,31,32

The presentation of C=C groups exhibited that, by oxidation of graphite into GO, the main structure of graphite layer was still reserved. The results of FT-IR synthesis demonstrated the successful synthesis of GO sheet.

33,34

The St-MA exhibits an absorption peak at 1729 cm–1, which could be assigned to the carbonyl group of maleate moiety in the modified starch. The absorption band at 1641 cm-1 is due to the (C=C) bond and non-symmetric deformation of the carboxylate groups of the maleate.

33,34

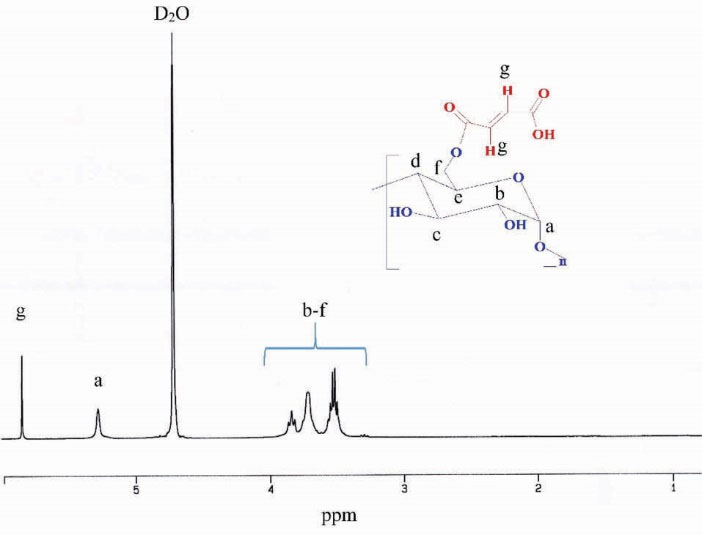

The (C–O) bond stretching of starch were observed at 1100-931 cm–1. The absorption peak at 2936 cm–1 is related to the (C–H) bond. The (O–H) stretching indicated a broadband from 3100 to 3500 cm–1. Also, 1H NMR spectrum of St-MA is shown in Fig. 2 to further confirm the structure of St-MA. The starch typical peaks of glucose ring protons (Hb–Hf) observed at 3.5–3.8 ppm. The Ha protons (proton of anomeric carbon) appeared at 5.2 ppm.

35

The protons of vinyl groups of maleate appear around 5.8 ppm which indicates that the starch was successfully functionalized with MA.

36

In the FT-IR spectrum of HCs, some characteristics peaks of GO and St-MA are overlapped with PNIPAAm peaks, however, new amide I (C=O stretching) and amide II (N–H bending) due to the amide group of PNIPAAm moiety are observed at 1649 cm–1 and 1544 cm–1, respectively. The (N–H) group of PNIPAAm, (O–H) groups in the starch and GO main structure indicated strong absorption at 3450 cm–1.

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of GO, St-MA, HC.

.

FT-IR spectra of GO, St-MA, HC.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectrum of St-MA in D2O.

.

1H NMR spectrum of St-MA in D2O.

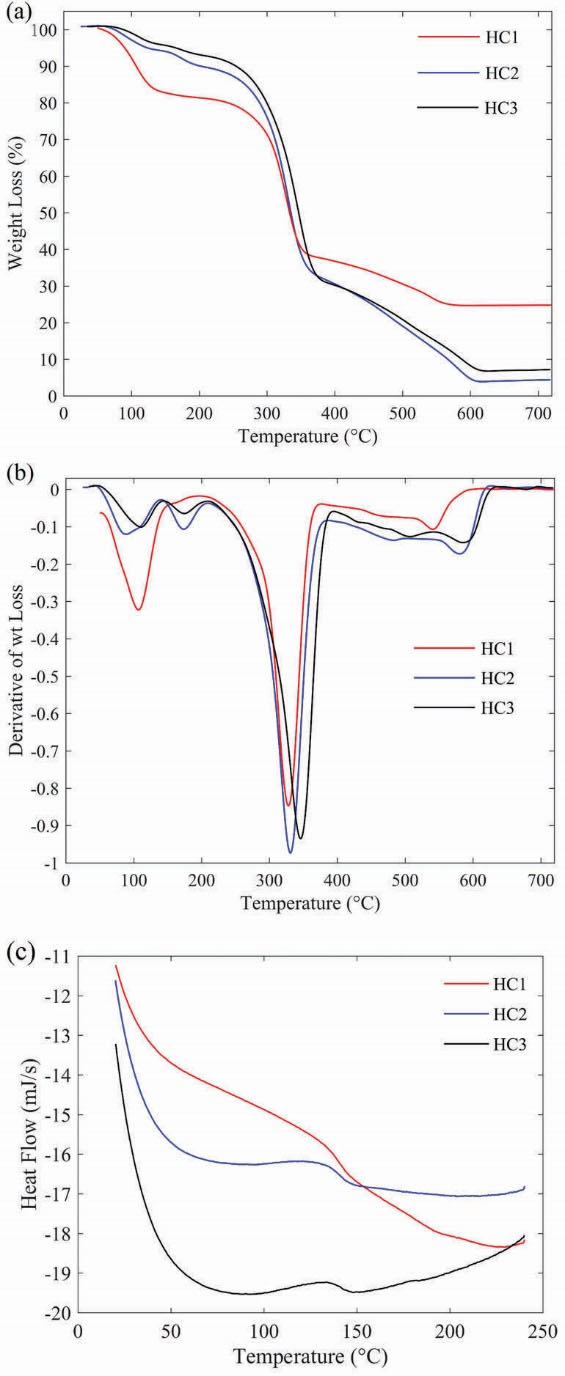

TGA and DSC investigation

The TGA was applied as a technique to define the composition and thermal stability of the as-prepared HC1-3. The major weight loss of GO occurs near to 200°C, which is due to the pyrolysis of labile oxygen-containing groups.

26

PNIPAAm exhibits one-stage degradation behavior at 400°C, and starch has maximum weight loss around 250-300°C.

37

The TGA and derivative TGA (DTGA) curves are shown in Fig. 3 for the HC1-3. The decomposition temperature of HC1-3 is 328, 332 and 347°C, respectively; which shows a slight increase with increasing of GO amount. The results indicated that GO, starch and PNIPAAm were incorporated in the composite structure and the interaction between GO with PNIPAAm and starch improved the thermal stability of the final composite.

Figure 3.

(a) TGA and (b) DTGA thermograms of HCs1-3; (c) DSC curves of HCs1-3.

.

(a) TGA and (b) DTGA thermograms of HCs1-3; (c) DSC curves of HCs1-3.

The glass transition temperature (Tg) of the prepared HCs were evaluated by DSC. As shown in Fig. 3(c), Tg is 132, 133 and 142°C for the synthesized HC1, HC2 and HC3, respectively. It is reported that Tg of PNIPAAm hydrogel is about 131.4°C. However, for the synthesized HC3, Tg is increased about 10°C which could be due to the increase of polymer chain interactions with each other and/or with hydrophilic groups of GO sheets and St-MA. St-MA can act as a chemical cross-linker and cause the strong interaction between polymer chains.

38

As shown in Fig. 3(c), differences in Tg of prepared HCs also could be due to the different weight percent of GO in the synthesized samples. The weight percent of GO in HC1, HC2 and HC3 are 3.36, 4.16 and 6.1 %, respectively. This confirms that at the same concentration of NIPAAm and St-MA, the endothermic peak corresponding to Tg shifts towards higher temperature with increasing the GO amount; which demonstrates that the higher GO concentration leads to more compact and cross-linked structure.

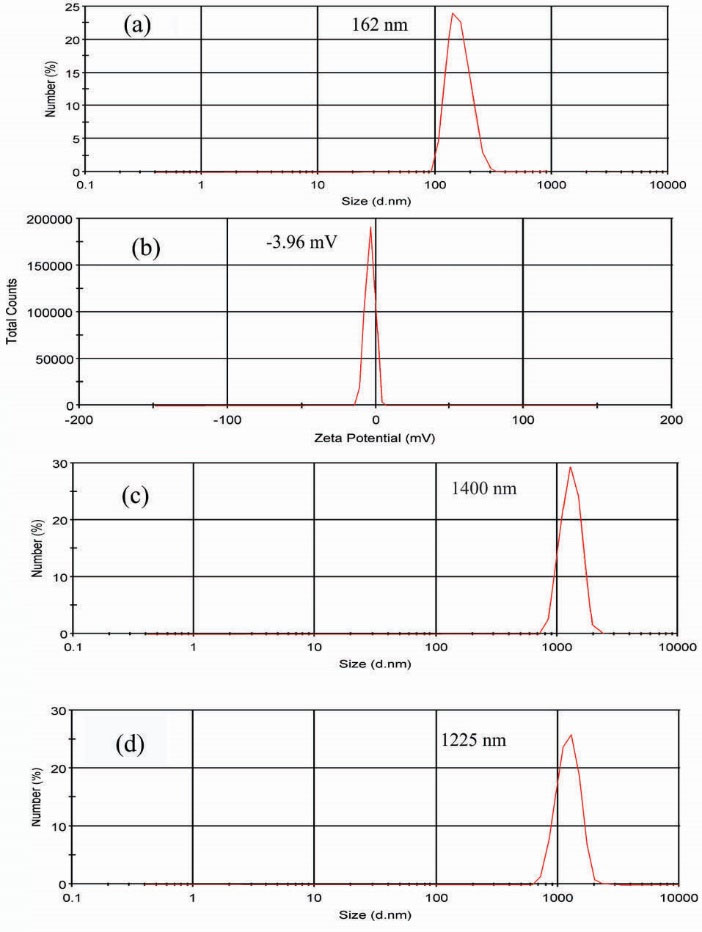

Size distributions of the hydrogel composites

Considering the GO unique 2D shape and ultra-small size as a graphitic nanocarrier,

27

HCs were produced by the polymerization of NIPAAm and St-MA in the presence of GO. The DLS method was applied to measure the size distribution and zeta potential of the prepared HCs solution at 25°C. As shown in Fig. 4(a, b), HC1 indicated the average size about 162 nm with the zeta potential of – 3.96 mV, which confirms that it has a slightly negative surface charge, maybe due to the free carboxylic groups on the surface of GO. The zeta potential 60-70 mV (negative) has been reported for the GO.

39

With considering the amount of GO in the prepared HCs in comparison with NIPAAm and St-MA, the obtained zeta potential could be reasonable. As indicated in Fig. 4(c, d), HC2 and HC3 are in microscale and it could be concluded that the higher amount of GO leads to the more compact and cross-linked structure which are unable to well dispersed in aqueous solution.

Figure 4.

(a) Size distribution and (b) zeta potential of HC1; (c), (d) size distribution of HC2 and HC3, respectively.

.

(a) Size distribution and (b) zeta potential of HC1; (c), (d) size distribution of HC2 and HC3, respectively.

Thermosensitive behavior of HCs

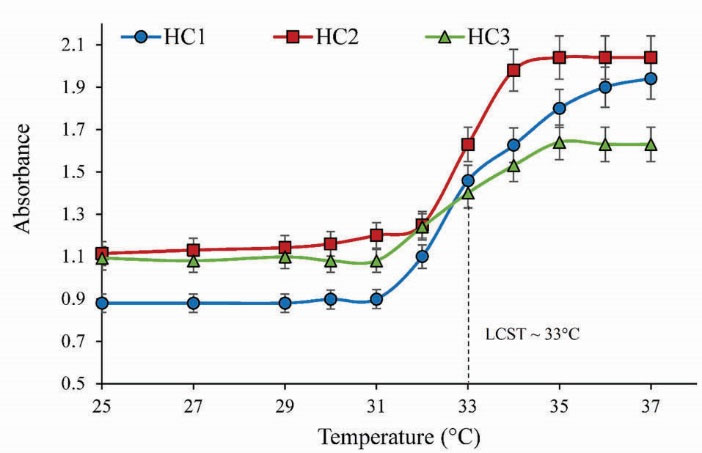

The phase transition behavior of HCs in PBS (pH= 7.4) was investigated by determining the optical absorbance at 541 nm in the range of 25-37°C and LCST was determined as a temperature when absorbance was increased 50% from the initial. Fig. 5 represents the change of absorbance upon temperature for HC1-3 with the concentration of 1 mg/mL. As shown in Fig. 5, HCs indicated the LCST around 33°C.

Figure 5.

LCST analysis of HCs in PBS (pH= 7.4) against temperature changes by UV-vis at 541 nm with concentration of 1 (mg/mL).

.

LCST analysis of HCs in PBS (pH= 7.4) against temperature changes by UV-vis at 541 nm with concentration of 1 (mg/mL).

Swelling/deswelling behavior of HCs

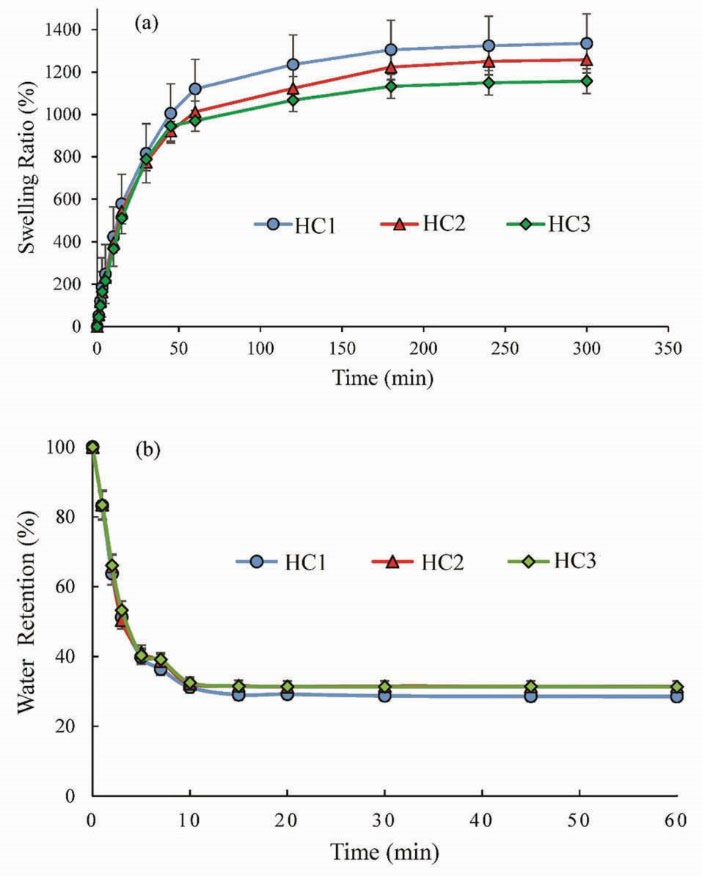

Swelling behavior of hydrogels is their most important property and usually is measured by gravimetric measurements of water uptake. Fig. 6(a) shows the swelling kinetics of HCs at room temperature in distilled water. As indicated in Fig. 6(a), the synthesized HCs exhibited fast water absorption and high swelling degree.

Figure 6.

(a) Swelling and (b) deswelling kinetics of HC1-3 in distilled water.

.

(a) Swelling and (b) deswelling kinetics of HC1-3 in distilled water.

Fig. 6(b) depicts the deswelling kinetics of HCs at 45°C changing with time. It is obvious that the prepared HCs indicated similar deswelling behavior. They have fast deswelling rate and could get to a half deswelling degree within 15 min. The swelling/deswelling results suggested that the prepared HCs are temperature responsive with fast response rate.

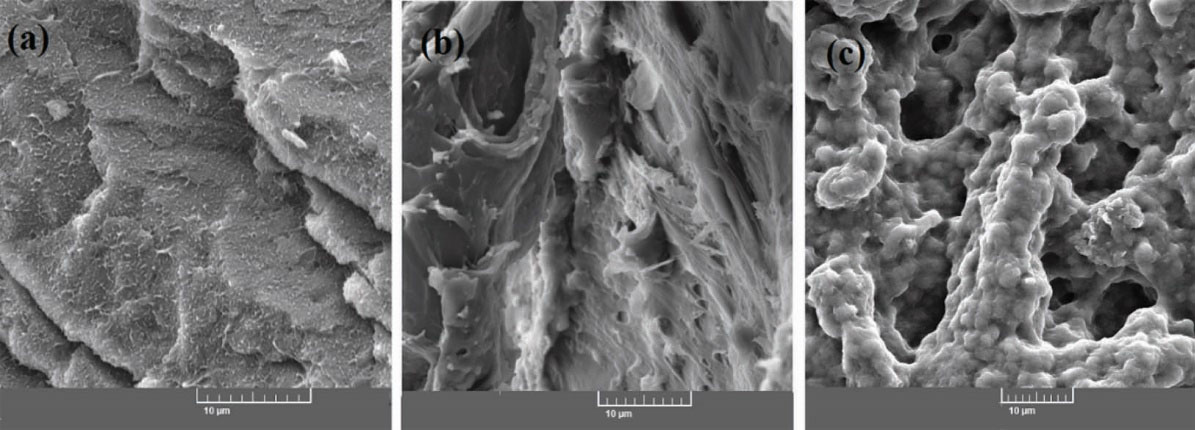

Internal network structure of hydrogel composites

Fig. 7 indicates SEM images of HCs prepared with different GO content. As indicated, the samples have a porous structure and the internal network structure of HCs could be affected by GO incorporation. The increase of GO loading leads to an increase of HCs’s network density, while the size of pores decreases. Due to the less crosslinked structure of HC1 in comparison with HC2 and HC3, HC1 could be dispersed well in water in DLS measurement. On the other hand, the SEM analysis was performed in the dried state in which HC1 may be aggregated.

Figure 7.

The SEM micrographs of (a) HC1, (b) HC2 and (c) HC3.

.

The SEM micrographs of (a) HC1, (b) HC2 and (c) HC3.

Cytotoxicity Study

The biocompatibility of vehicles as DDSs is an important factor for their applications. The cytotoxicity of HC1 was evaluated on A549 cells. Fig. 8 shows the viability of the A549 cells against different concentrations of HC1 after incubation for 24, 48, and 72 hours. As indicated, the samples show not significant toxicity, which suggests that the prepared HCs are biocompatible and applicable for DDSs.

Figure 8.

The cell viability of A549 after incubation with HC1-3 for 24, 48 and 72 hours.

.

The cell viability of A549 after incubation with HC1-3 for 24, 48 and 72 hours.

Hemolytic properties of the synthesized HCs

For in vivo application of NPs, they should not damage the blood constituents.

40

Therefore, hemolysis test was performed as a standard method to evaluate the compatibly of synthesized HCs with the blood component. The different concentration of HC1 in PBS was exposed to the whole blood. Distilled water and PBS with pH = 7.4 were applied as a positive and negative control, respectively. Fig. 9 (a) shows the optical photograph of the supernatants after the samples were centrifuged and Fig. 9 (b) indicates UV-vis quantification of hemolysis. The results demonstrate that a negligible hemolysis (less than 5%) was observed for HC1 solutions with a concentration of 10-500 ppm after 3 hours incubation with blood. The obtained results suggest that the prepared HCs are hemocompatible which make them suitable for biomedical applications.

Figure 9.

Hemocompatibility of HC1 (a) photograph and (b) UV-vis quantification of supernatant.

.

Hemocompatibility of HC1 (a) photograph and (b) UV-vis quantification of supernatant.

Discussion

The performance of PNIPAAm hydrogel as intelligent material could be improved using GO.

41

In this work, PNIPAAm/GO HCs were synthesized by a different cross-linker agent. Therefore, GO was synthesized using a modified Hummers’ method and then starch-maleate (St-MA) was produced by the esterification of starch with maleic anhydride. The St-MA with double bonds can act as a biodegradable cross-linker agent, and make possible the polymerization of other monomers and cross-linking to produce HCs. The HCs were prepared via NIPAAm polymerization in the matrix of GO/St-MA by the free radical polymerization using H2O2 as an initiator and THPC as an oxygen scavenger. The obtained experimental results confirmed that HCs could not be formed in the absence of THPC at 60°C. The molecular oxygen is an effective inhibitor for free radical polymerization; therefore, in the presence of THPC antioxidant (strong and rapid oxygen scavenger), the efficacy of the polymerization could be enhanced remarkably.

42

In comparison with the reported PNIPAAm/GO nanocomposite hydrogels,

27,41

the use of St-MA as biodegradable and non-toxic cross-linker could be considered the new route for the chemical crosslinking of GO with other polymeric components. HC1-3 was synthesized with different feed ratio of GO as presented in Table 1. The obtained results indicated that the GO content can influence the physicochemical properties of HCs. The TGA results (Fig. 3) confirmed the increase of thermal stability of HCs with increasing the GO content. Also, DSC analysis demonstrated that the Tg of HCs increased with the increase of GO moieties which could be due to a more compact structure of cross-linked HCs. This is reasonable; since, the amphiphilic GO sheets could be dispersed well in water before polymerization via H-bonding and intercalated with PNIPAAm networks during polymerization.

43

The SEM results (Fig. 7) further demonstrated this issue where the increase of GO loading, cause to the increase of network density and the decrease of the pore sizes.

41

Size distribution results indicated that HC1 was well dispersed in solution and the size distribution of particles is about 160 nm, while HC2 and HC3 with dense network could not be dispersed well and have a size distribution around 1 μm. Furthermore, the compact structure could influence the swelling property, where the HC3 indicates lower swelling ratio in comparison with HC1. Generally, GO has an effective influence on the equilibrium swelling ratio of prepared hydrogels. This might be illustrated with the H-bond formation between hydrophilic groups of GO and water molecules, as well as amide groups in PNIPAAm and hydrophilic groups of St-MA which leads to the increase of swelling ratio of hydrogels. On the other hand, as illustrated in size distribution section (Fig. 4), the increase in GO content leads to the more compact hydrogels, because of intermolecular interactions of GO sheets with PNIPAAm and St-MA, which results in the decrease of the equilibrium swelling ratio.

41

In this work, the weight percent of GO in HC1, HC2 and HC3 are 3.36, 4.16 and 6.1 %, respectively. Therefore, it is expected to decrease equilibrium swelling ratio with an increase in the amount of GO, as indicated in Fig. 6(a). Also, it is worth mentioning that when the GO content is more than a certain value, the interaction of GO with water molecules is weaker than the intermolecular interactions of GO sheets with PNIPAAm moieties, and therefore, leads to absorb less water content by the hydrogel structure.

41

Also, the LCST determination of HCs revealed the LCST around 33°C for samples in PBS (pH = 7.4). Generally, the phase transition of PNIPAAm based hydrogels occurred around 32°C and they are in the hydrophilic state below the LCST and turn into hydrophobic and collapsed above the LCST. It is well known that the LCST can be modulated to higher and lower values by incorporating hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties, respectively.

6

Therefore, GO as hydrophilic moiety cause to the slight increase of the phase transition temperature of the as-prepared HCs.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a facile strategy for thermoresponsive HCs by in-situ polymerization of NIPAAm in a colloid solution of GO where maleate modified starch as cross-linker, THPC as oxygen scavenger and H2O2 as initiator were applied. Thermal stability, phase transition, size distribution and cross-linking of HCs increased with increase of GO content. Swelling/de-swelling investigation indicated high swelling ratio with fast response rate. Finally, cytotoxicity assays confirmed that HCs are biocompatible and hemocompatible which suggests they are beneficial for future biomedical applications.

Ethical approval

There is no to be declared.

Competing interests

No competing interests to be disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Chemical and Petroleum Engineering at University of Tabriz and Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for the technical support.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

simple

-

√ HCs of N-Isoproylacrylamide/Starch-Maleate/ GO as a

class of intelligent material were developed and characterized.

-

√ HCs were synthesized by a facile in-situ free radical

polymerization method.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ Starch was modified with maleic anhydride and used as

biodegradable cross-linker instead of toxic chemical crosslinkers.

-

√ H2O2 was used as an initiator in the presence of tetrakis

(hydroxymethyl) phosphonium chloride (THPC) as an

oxygen scavenger.

-

√ The obtained HCs indicated high swelling ratio, fast

response rate, hemocompatibility and biocompatibility

which make them suitable for biomedical applications.

References

- Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Murray JC. Long-circulating and target-specific nanoparticles: theory to practice. Pharmacol Rev 2001; 53:283-318. [ Google Scholar]

- Alsaleh FM, Smith FJ, Keady S, Taylor KM. Insulin pumps: from inception to the present and toward the future. J Clin Pharm Ther 2010; 35:127-38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01048.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Peppas NA. Hydrogels in medicine and pharmacy: properties and applications:. CRC PressI Llc 1987. doi: 10.1002/pi.4980210223 [Crossref]

- Peppas NA, Khare AR. Preparation, structure and diffusional behavior of hydrogels in controlled release. Adv drug deliv rev 1993; 11:1-35. doi: 10.1016/0169-409X(93)90025-Y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Brannon-Peppas L. Preparation and characterization of crosslinked hydrophilic networks. Absorbent Polymer Technology, Studies in Polymer Sci 1990; 8:45-66. [ Google Scholar]

- Fathi M, Barar J, Aghanejad A, Omidi Y. Hydrogels for ocular drug delivery and tissue engineering. Bioimpacts 2015; 5:159-64. doi: 10.15171/bi.2015.31 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Qiao M, Chen D, Ma X, Liu Y. Injectable biodegradable temperature-responsive PLGA-PEG-PLGA copolymers: synthesis and effect of copolymer composition on the drug release from the copolymer-based hydrogels. Int J Pharm 2005; 294:103-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.01.017 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hoffman AS. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2002; 54:3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ron ES, Bromberg LE. Temperature-responsive gels and thermogelling polymer matrices for protein and peptide delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 1998; 31:197-221. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(97)00121-X [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Park K. Environment-sensitive hydrogels for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2001; 53:321-39. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00203-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hoare TR, Kohane DS. Hydrogels in drug delivery: progress and challenges. Polymer 2008; 49:1993-2007. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2008.01.027 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi A, Okano T. Pulsatile drug release control using hydrogels. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2002; 54:53-77. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00243-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Frisken BJ. Influence of secondary components on the synthesis of self-cross-linked N-isopropylacrylamide microgels. Langmuir 2005; 21:545-51. doi: 10.1021/la0485982 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fathi M, Entezami AA, Ebrahimi A, Safa KD. Synthesis of thermosensitive nanohydrogels by crosslinker free method based on N-isopropylacrylamide: Applicable in the naltrexone sustained release. Macromol Res 2013; 21:17-26. doi: 10.1007/s13233-012-0181-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Lorenzo C, Blanco-Fernandez B, Puga AM, Concheiro A. Crosslinked ionic polysaccharides for stimuli-sensitive drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013; 65:1148-71. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.04.016 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Likhitkar S, Bajpai A. Magnetically controlled release of cisplatin from superparamagnetic starch nanoparticles. Carbohydr Polym 2012; 87:300-8. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.07.053 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhou HY, Zhang YP, Zhang WF, Chen XG. Biocompatibility and characteristics of injectable chitosan-based thermosensitive hydrogel for drug delivery. Carbohydr Polym 2011; 83:1643-51. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.10.022 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Belbekhouche S, Ali G, Dulong V, Picton L, Le Cerf D. Synthesis and characterization of thermosensitive and pH-sensitive block copolymers based on polyetheramine and pullulan with different length. Carbohydr Polym 2011; 86:304-12. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.04.053 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Stankovich S, Dikin DA, Dommett GH, Kohlhaas KM, Zimney EJ, Stach EA. Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 2006; 442:282-6. doi: 10.1038/nature04969 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Robinson JT, Sun X, Dai H. PEGylated nanographene oxide for delivery of water-insoluble cancer drugs. J Am Chem Soc 2008; 130:10876-7. doi: 10.1021/ja803688x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zhang X, Liu Z, Ma Y, Huang Y, Chen Y. High-efficiency loading and controlled release of doxorubicin hydrochloride on graphene oxide. J Phys Chem C 2008; 112:17554-8. doi: 10.1021/jp806751k [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Li Y, Li Y, Li J, Deng Z. Noncovalent DNA decorations of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide toward water-soluble metal–carbon hybrid nanostructures via self-assembly. J Mater Chem 2010; 20:900-6. doi: 10.1039/B917752C [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Tao H, Yang K, Feng L, Cheng L, Shi X. A functionalized graphene oxide-iron oxide nanocomposite for magnetically targeted drug delivery, photothermal therapy, and magnetic resonance imaging. Nano Res 2012; 5:199-212. doi: 10.1007/s12274-012-0200-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cheng HK, Sahoo NG, Tan YP, Pan Y, Bao H, Li L. Poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposites filled with poly(vinyl alcohol)-grafted graphene oxide. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2012; 4:2387-94. doi: 10.1021/am300550n [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Bao H, Sahoo NG, Wu T, Li L. Water‐Soluble Poly (N‐isopropylacrylamide)–Graphene Sheets Synthesized via Click Chemistry for Drug Delivery. Adv Funct Mater 2011; 21:2754-63. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201100078 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bao H, Pan Y, Ping Y, Sahoo NG, Wu T, Li L. Chitosan-functionalized graphene oxide as a nanocarrier for drug and gene delivery. Small 2011; 7:1569-78. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100191 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Wu P. A one-step strategy for thermal-and pH-responsive graphene oxide interpenetrating polymer hydrogel networks. J Mater Chem 2011; 21:4095-7. doi: 10.1039/C1JM10276A [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tay SH, Pang SC, Chin SF. Facile synthesis of starch-maleate monoesters from native sago starch. Carbohydr Polym 2012; 88:1195-200. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.01.079 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kim G-C, Li Y-Y, Chu Y-F, Cheng S-X, Zhuo R-X, Zhang X-Z. Nanosized temperature-responsive Fe 3 O 4-UA-g-P (UA-co-NIPAAm) magnetomicelles for controlled drug release. Eur Polym J 2008; 44:2761-7. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2008.07.015 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shelma R, Sharma CP. Development of lauroyl sulfated chitosan for enhancing hemocompatibility of chitosan. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2011; 84:561-70. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.02.018 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kakran M, Sahoo NG, Bao H, Pan Y, Li L. Functionalized graphene oxide as nanocarrier for loading and delivery of ellagic Acid. Curr Med Chem 2011; 18:4503-12. doi: 10.2174/092986711797287548 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Wang Y, Huang X, Ma Y, Huang Y, Yang R. Multi-functionalized graphene oxide based anticancer drug-carrier with dual-targeting function and pH-sensitivity. J mater chem 2011; 21:3448-54. doi: 10.1039/C0JM02494E [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Stankovich S, Piner RD, Nguyen ST, Ruoff RS. Synthesis and exfoliation of isocyanate-treated graphene oxide nanoplatelets. Carbon 2006; 44:3342-7. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2006.06.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Paredes JI, Villar-Rodil S, Martinez-Alonso A, Tascon JM. Graphene oxide dispersions in organic solvents. Langmuir 2008; 24:10560-4. doi: 10.1021/la801744a [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Shan H, Sun J, Weng Y, Wang X, Xiong J. Facile preparation of corn starch nanoparticles by alkali-freezing treatment. RSC Advances 2013; 3:13406-11. doi: 10.1039/C3RA41610K [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Fathi M, Zangabad PS, Aghanejad A, Barar J, Erfan-Niya H, Omidi Y. Folate-conjugated thermosensitive O-maleoyl modified chitosan micellar nanoparticles for targeted delivery of erlotinib. Carbohydr Polym 2017; 172: 130-41. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.05.007

- Fathi M, Entezami AA, Arami S, Rashidi M-R. Preparation of N-isopropylacrylamide/itaconic acid magnetic nanohydrogels by modified starch as a crosslinker for anticancer drug carriers. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater 2015; 64:541-9. doi: 10.1080/00914037.2014.996703 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang XZ, Wu DQ, Chu CC. Synthesis, characterization and controlled drug release of thermosensitive IPN-PNIPAAm hydrogels. Biomaterials 2004; 25:3793-805. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.065 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Si Y, Samulski ET. Synthesis of water soluble graphene. Nano Lett 2008; 8:1679-82. doi: 10.1021/nl080604h [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lee D-W, Powers K, Baney R. Physicochemical properties and blood compatibility of acylated chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr polym 2004; 58:371-7. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2004.06.033 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Li Y, Wang W, Ji Q, Xia Y. Temperature-sensitive poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)/graphene oxide nanocomposite hydrogels by in situ polymerization with improved swelling capability and mechanical behavior. Eur Polym J 2013; 49:389-96. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2012.10.034 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fathi M, Farajollahi AR, Entezami AA. Synthesis of fast response crosslinked PVA-g-NIPAAm nanohydrogels by very low radiation dose in dilute aqueous solution. Radiat Phys Chem 2013; 86:145-54. doi: 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2013.02.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi K, Takehisa T, Fan S. Effects of clay content on the properties of nanocomposite hydrogels composed of poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) and clay. Macromolecules 2002; 35:10162-71. doi: 10.1021/ma021301r [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]