BioImpacts. 8(1):23-30.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2018.04

Original Research

Caralluma umbellata Haw. protects liver against paracetamol toxicity and inhibits CYP2E1

Pavan Kumar Bellamakondi 1, *, Ashok Godavarthi 1, Mohammed Ibrahim 2

Author information:

1Radiant Research Services Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, India

2Nizam Institute of Pharmacy, Nalgonda, India

Abstract

Introduction:

Paracetamol is a potent hepatotoxin and may cause severe acute hepatocellular injury. The present study was intended to assess the hepatoprotective potential of Caralluma umbellata Haw. (Asclepiadaceae) (C. umbellata ) against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in vitro and in vivo experimental models.

Methods:

Preliminary analysis for antioxidant and hepatoprotective property was evaluated for methanolic (MCU), aqueous (ACU) and hydro methanolic (HCU) extracts of C. umbellata using in vitro cell-free antioxidant such as DPPH, ABTS, nitric oxide, lipid peroxidation models and cell-based hepatoprotective study using BRL3A cells. In vivo, hepatoprotective activity was studied in paracetamol treated male Wistar albino rats. Furthermore, molecular mechanism behind the protective effect of MCU was explored by RT PCR technique by utilizing cytochrome P450 (CYP) CYP2E1.

Results:

C. umbellata extracts especially, MCU showed a better antioxidant property. MCU offered significant dose-dependent protection against paracetamol-induced hepatic damage in both in vitro and in vivo assays by improving all the biochemical findings towards the normal range. In a mechanism-based study, MCU has offered significant down-regulation (p < 0.05) of CYP2E1. These findings were in line with the hepatoprotective activity findings where MCU showed significant protection.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, these findings suggest that MCU possess hepatoprotective activity. One of the possible mechanisms behind the protective effect of MCU is found to be inhibition of CYP2E1.

Keywords: Antioxidant,

Caralluma umbellata

, BRL3A, CYP2E1, Hepatoprotection

Copyright and License Information

© 2018 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a potentially fatal complication of severe hepatic illness resulting from viral hepatitis or drug use.

1

In India, drug-induced ALF has been found to be around 6-8% of total ALF with next to viral hepatitis.

2

Paracetamol is considered as one of the major causes for drug-induced ALF, and has been extensively studied for its liver damage.

3,4

The mechanism behind paracetamol toxicity is mainly due to the reduction of hepatocyte GSH and increased CYP2E1 activity where paracetamol is metabolized to an extremely reactive toxic metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) along with generation of reactive oxygen species in augmenting oxidative stress.

3,5,6

Thus the search for new elements which may reverse and/or overcome the oxidative stress damage and manage the expression of CYP2E1 could protect the liver against a paracetamol-induced hepatocellular oxidative injury as previously described.Crude extracts and the phytoconstituents isolated from the medicinal herbs have been well documented for their antioxidant and CYP inhibitory properties. Owing to the minimal side effects and low production cost of these phytoconstituents, it would be encouraging to discover new phytoconstituents from less explored plants and evaluate the preventive action of these phytoconstituents on the hepatocellular and oxidative injury.

7,8

The genus Caralluma (Asclepiadaceae) comprises around 200 species distributed throughout Africa and Asia, widely grows in India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

9

Few species from the genus Caralluma qualify as ‘safe to eat’. These plants form the central part of the traditional medicine system and are used for the treatment of diabetes and stomach disorders.

10,11

Earlier studies have illustrated their anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive, anti-ulcerogenic anti-oxidant and hepatoprotective activities.

12

The key phytochemical ingredients in Caralluma are pregnane glycosides, flavone glycosides, megastigmane glycosides, bitter principles, triterpenes and saponins.

13-15

Caralluma umbellata Haw. is a wild growing succulent perennial herb in Tirupati, Chitoor of Andhra Pradesh, India. Traditionally this plant has been used to relieve stomach disorders and abdominal pains.

12

Pregnane glycosides such as carumbelloside-I to carumbelloside-V, and a flavone glycoside, luteolin-4′-O-neohesperidoside have been found to be major bioactive compounds which exhibit anti-inflammatory and antininociceptive activities.

16

The treatment of liver diseases with allopathic drugs is often associated with serious side effects. Hence plants which consist of several classes of phytoconstituents may offer protection at multiple targets. Our preliminary studies with C. umbellata showed the presence of flavonoids and phenols in extracts and further in vitro antioxidant tests showed promising antioxidant potential. In view of these preliminary findings, we hypothesized that C. umbellata may protect against hepatotoxicity caused by oxidative stress. Hence the present study was focused on the hepatoprotective potential of C. umbellata.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), 5-Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced (NADPH), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonicacid) diammonium salt (ABTS) and Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM), trichloroaceticacid (TCA), thiobarbituricacid (TBA), folin ciocalteau and trypsin were procured from Hi-Media Labs Pvt. Ltd (Mumbai, India). 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and Silymarin were procured from Sigma Aldrich (MO, USA). Kits for serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total protein (TP) and total bilirubin (TB) were procured from Erba diagnostic (Mannheim, Germany). All other chemicals used were analytical grade and obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA), Merck (Bangalore, India) and Sd Fine Chem (Mumbai, India). Tri reagent from G Biosciences (St. Louis, USA), oligo dT primer from Eurofins (Bangalore, India), Revert Aid Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo scientific, India), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) master mix from Aristogene (Bangalore, India), Rodent pellet diet from Gold Mohr (Lipton India Ltd, Bangalore, India), Rat (BRL3A) liver cell line was acquired from National Centre for Cell Science (Pune, India).

Plant collection and extraction

The plant material was collected during the month of April 2011 from Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, India. The authentication was done by a Botanist, Dr. Madava Chetty, S. V University, Tirupati by comparing with the housed authenticated specimens. Shade-dried and powdered raw material was extracted with methanol (MCU), water (ACU) successively and further extracting with methanol: water (60:40) (HCU) with Soxhlet apparatus, the extracted materials were dried under reduced pressure.

Phytochemistry

The extracts were analyzed for the presence of phytoconstituents as described by Harborne.

17

The total phenol and flavonoid content was quantified as described earlier, Chandran et al.

18

HPLC study of MCU

The presence of phytoconstituents, β-sitosterol, lupeol and quercetin were investigated by HPLC using Waters HPLC instrument (Kyoto, Japan) fitted with a dual pump LC-20AD binary system with photodiode array (PDA) detector SPD-M20A, Merck RPC18 column (I.D. 4.6 x 250 mm, 5 mm). MCU was dissolved in methanol and injected. Gradient elution was carried out with methanol: phosphate buffer (50 M) at pH 3, (70:30) and the flow rate was adjusted to 1.0 mL/min with 20 µL injection volume, detection by UV at 250 nm.

In vitro antioxidant activity

The extracts were evaluated for their antioxidant capacity using the DPPH radical, ABTS radical cation, nitric oxide radical, superoxide radical, lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity. In addition total antioxidant capacity, reducing power potential was also determined.

19

In vitro hepatoprotective activity

Cell culture and treatment protocol

BRL3A cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics, maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator under a humidified condition at 37°C. For the hepatoprotective study, different test extracts were chosen based on previously published data.

20

For evaluating the cytoprotection in terms of cell viability, MTT assay was used.

20

Cells were grown in 96-well plates at 1000 cells/well and allowed to adhere overnight. Then, they were treated with MCU, ACU and HCU (350 µg/mL) along with paracetamol (2000 µg/mL), and incubated for 24 h. Further, the toxicant control as paracetamol alone and cell control with media alone were also maintained simultaneously. Silymarin (250 µg/mL) was used as a standard.

Cell lysates preparation

BRL3A cells were grown to confluency in 60 mm Petri dishes. The treatment was performed with MCU (150 and 350 µg/mL) along with paracetamol. Another set was maintained which consists of test extract MCU (150 and 350 µg/mL), paracetamol alone and control with culture media containing 0.1% DMSO in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS and incubated for 24 hours. Cell lysates were prepared by using in lysis buffer containing the protease inhibitor. The supernatant was prepared by centrifuging the samples at 10 000 rpm for 10 minutes. The clear supernatant was used for the assessment of antioxidant activity. Protein estimation was estimated using the Bradford protein assay, using bovine serum albumin as a protein standard.

21

The separated cell supernatants were analyzed for estimating reduced GSH levels and TBARS levels.

22,23

The level of GSH (glutathione) was expressed as nmol of GSH/mg protein using extinction coefficient of 14150 M-1 cm-1. The level of lipid peroxidation was expressed as nmol of MDA (malondialdehyde)/mg protein using extinction coefficient of 1.56 × 105 M-1 cm-1.

Semi-quantitative RT PCR of CYP2E1

Treatment of BRL3A

The treatment for gene expression study in 60 mm Petri dishes was followed as described earlier. After incubation for 24 hours, the supernatant solution from the cultures was discarded and cultures were processed for total RNA extraction.

Gene expression study

Total RNA was extracted from treated cultures using Tri-reagent, according to the protocol described by the manufacturer. cDNAs were prepared from isolated total RNA using oligo dT primer and RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase and then PCR amplification using gene-specific primers. Specific primers for CYP2E1 and GAPDH primers were selected as per Yao et al, and Gene runner, ver 3.05, Hasting software Inc., respectively for amplification.

24

The primers for CYP2E1 were forward 5′ CTC CTC GTC ATA TCC ATC TG 3′ and reverse 5′ GCA GCC AAT CAG AAA TGT GG 3′ and for GAPDH forward 5′GTG AAG GTC GGT GTG AAC GG 3′ and 5′ CAC GCC ACA GCT TTC CAG AG 3′ respectively. PCR (MJ Mini Thermocycler, Bio-Rad California, USA) was carried out in a final reaction volume of 50 μL PCR master mix with 10 pmol of primers. PCR conditions were set at initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes followed by 30 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing of primers at 57°C for 30 seconds (CYP2E1), 59°C for 30 seconds (GAPDH), extension at 72°C for 30 seconds and final extension at 72°C for 2 minutes. Quantification of PCR products was done by using digital imaging (Alpha Digi DOC, USA) and relative sample expression levels were calculated using Alpha view, version 3.3.1.0., Cell Biosciences Inc. (Santa Clara, USA), and were expressed relative to GAPDH.

In vivo hepatoprotective activity in rats against paracetamol-induced toxicity

Experimental animals and diets

Healthy non pregnant female Wistar rats (150 g–200 g) were used for acute toxicity study and healthy young adult male Wistar rats were used for studies on the heptoprotection. Animals were acclimatized for 1 week prior to the study. They were maintained at 27 ± 3°C with relative humidity of 65 ± 10%, and were exposed to 12-hour light and 12-hour dark cycle. Animals were provided standard rodent pellet diet (Gold Mohr, Lipton India Ltd) and reverse osmosis purified water.

Experiment

Thirty rats were divided into 5 groups of six in each group. Test extract MCU (200 and 400 mg/kg body weight) and standard silymarin (100 mg/kg body weight) were prepared in 0.5% (w/v) sodium carboxymethylcellulose solution (CMC). Group 1 was designated as normal control treated plain CMC. Group 2 was treated as toxicant control with 1 mL CMC. Group 3 was treated with silymarin (100 mg/kg body weight). Groups 4 and 5 were treated with MCU (200 and 400 mg/kg body weight).

The animals were treated with indicated doses, orally for 5 consecutive days. On the sixth day, all animals, except the ones in the control group, were treated with paracetamol (2 g/kg bodyweight p.o) and 24 hours following the paracetamol administration, the blood samples were collected from retro-orbital plexus. The AST, ALT, ALP, total bilirubin and total protein concentrations were measured using the respective diagnostic kits supplied by Erba.

25

The animals were sacrificed and the livers were preserved in formalin.

26

Statistical analysis

The IC50 values were calculated from dose-dependent curves and expressed as mean ± SD. The data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA). The difference between the means was considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Phytochemical study

As mentioned in the supplementary Table 1, the preliminary phytochemical analysis indicates the presence of carbohydrates, sterols, triterpenoids, phenols, flavonoids, saponins and glycosides in all extracts, and in a quantitative study for flavonoids and total phenols. The content of flavonoids was highest in MCU (56.90 ± 1.57 mg gallic acid equivalent/g dry weight), followed by HCU and ACU which showed 12.74 ± 0.33, 8.73 ± 0.34 and 2.87 ± 0.21 mg gallic acid equivalent/g dry weight, respectively. Total phenolic content also varied among the samples. MCU showed the highest levels (12.74 ± 0.33), followed by HCU (8.73 ± 0.34) and ACU (2.87 ± 0.21 mg gallic acid equivalent/g, dry weight respectively).

Table 1.

In vitro hepatoprotective study in BRL3A cell line

|

Group No.

|

Experimental group

|

Cytotoxicity over control (%)

|

GSH

|

MDA

|

| Control-I |

| 1 |

Normal control (0.1% DMSO, v/v) |

- |

0.828 ± 0.016 |

6.123 ± 0.87 |

| 2 |

MCU (350 µg/mL) |

8.88 ± 0.6 |

0.761 ± 0.018 |

7.41 ± 0.84 |

| 3 |

MCU (150 µg/mL) |

7.07 ± 1.06 |

0.806 ± 0.016 |

8.49 ± 0.84 |

| Toxicant control-II |

| 4 |

Paracetamol (2000 µg/mL) |

49.74 ± 0.54 |

0.527 ± 0.025###

|

13.25 ± 1.13###

|

| MCU treatment-III |

| 5 |

MCU (350 µg/mL)+ Paracetamol |

30.86 ± 1.86***

|

0.605 ± 0.015**

|

10.05 ± 0.69**

|

| 6 |

MCU (150 µg/mL)+ Paracetamol |

24.61 ± 0.8***

|

0.578 ± 0.09*

|

10.50 ± 0.88*

|

| Silymarin treatment-IV |

| 7 |

Sliymarin (250 µg/mL)+ Paracetamol |

10.73 ± 1.36***

|

0.679 ± 0.047 ***

|

8.07 ± 0.37 ***

|

Each values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Differences were considered to be statistically significant, if ###P < 0.001 compared with control and *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with paracetamol group. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post test. MCU, methanolic extract from C. umbellata ; GSH, glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde.

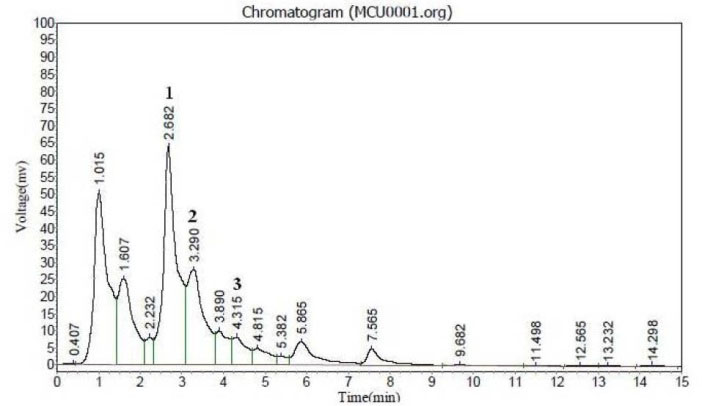

HPLC analysis of MCU

HPLC study was done to standardize MCU by analyzing three phytoconstituents such as lupeol, β-sitosterol and quercetin by comparing reference standards. HPLC chromatogram showed the presence of all three phytoconstituents at retention times 2.682 (lupeol), 3.290 (β-sitosterol) and 4.315 (quercetin) at 250 nm (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

HPLC UV chromatogram of MCU. Detection was recorded at 254 nm. (1) Lupeol, (2) β sitosterol, (3) Quercetin.

.

HPLC UV chromatogram of MCU. Detection was recorded at 254 nm. (1) Lupeol, (2) β sitosterol, (3) Quercetin.

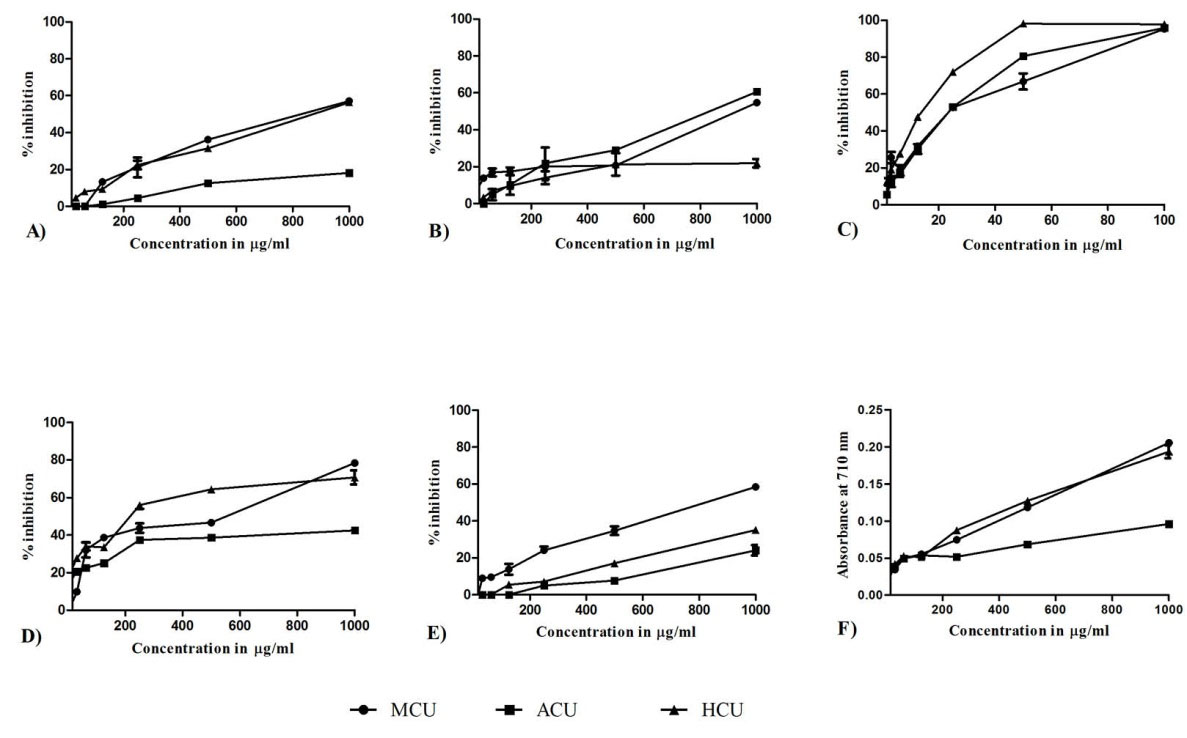

In vitro antioxidant assays

DPPH radical scavenging activity

The extracts showed moderate capacity, IC50 values varied from 799.9 ± 10.00 to >1000 µg/mL, among them, methanolic extract showed higher activity with IC50 value of 799.9 ± 10.00 µg/mL (Fig. 2 A).

Fig. 2.

In vitro antioxidant activity of test extracts. (A) DPPH, (B) Nitric oxide, (C) ABTS, (D) Lipid peroxidation, (E) Alkaline DMSO and (F) ferric ion reducing assay. MCU- C. umbellata methanolic extract, ACU- C. umbellata aqueous extract and HCU C. umbellata hydro methanolic extract. Each values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

.

In vitro antioxidant activity of test extracts. (A) DPPH, (B) Nitric oxide, (C) ABTS, (D) Lipid peroxidation, (E) Alkaline DMSO and (F) ferric ion reducing assay. MCU- C. umbellata methanolic extract, ACU- C. umbellata aqueous extract and HCU C. umbellata hydro methanolic extract. Each values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Nitric oxide radical inhibition assay

The extracts have moderate inhibition capacity against nitric oxide radical. Among them ACU showed maximum activity with IC50 value at 791.17 ± 4.71 µg/mL followed by MCU at 873.3 ± 5.8 µg/mL and HCU at 1000 µg/mL (Fig. 2B).

ABTS radical scavenging assay

The extracts were found to have good scavenging activity against ABTS radical, IC50 value ranging from 11.53 ± 0.47 to 20.9 ± 0.4 µg/mL. HCU showed stronger activity with IC50 of 11.53 ± 0.47 µg/mL (Fig. 2C).

Total antioxidant capacity

MCU possessed highest total antioxidant capacity with 355.03 ± 5.68 mg equivalent to ascorbic acid content per g of extract, followed by HCU and ACU at 284.56 ± 1.78, 107.04 ± 2.84 mg/g respectively.

Lipid peroxidation inhibition study

HCU was found to be effective in inhibiting lipid peroxidation, which was followed by MCU at IC50 of 204.57 ± 9.61 and 314.60 ± 8.8 µg/mL respectively, ACU has >1000 µg/mL (Fig. 2D).

Superoxide scavenging inhibitory activity

The extracts showed moderate scavenging capacity against generated superoxide radicals. Among extracts, MCU showed moderate activity with IC50 808.5 ± 8.7 µg/ml (Fig. 2E).

Reducing power assay

From reducing power data, MCU was found to have high reducing potential as depicted in Fig. 2F.

Cytoprotective effect of test extracts in BRL3A cells

Table 1 presents the cytotoxicity, MDA levels and GSH levels in the BLR3A cell lines exposed to different treatments. Treatment with paracetamol-induced 49.74 ± 0.54% cell death, while treatment with 150 µg/mL and 350 µg/mL MCU significantly reduced paracetamol induced cell death to 30.86 ± 1.86% and 24.61 ± 0.8, respectively. Similarly, paracetamol the treatment significantly reduced the GSH and MDA levels in cells, while treatment with MCU restored GSH and MDA to near normal levels. Silymarin was used a positive control also exhibited the similar trend in the activity.

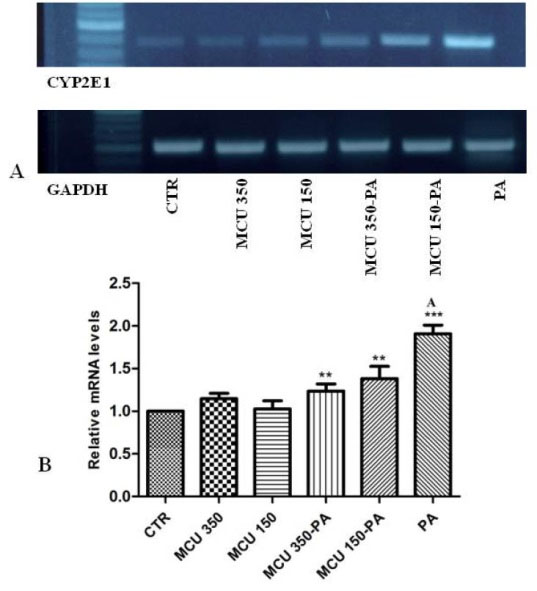

CYP2E1 RT PCR

Paracetamol treatment significantly increased expression of CYP2E1 (P < 0.001), while MCU co-treatment with paracetamol reduced the expression of CYP2E1 (P < 0.05). The treatment with MCU, in the absence of paracetamol, did not show significant fold expression as compared to control; indicating that MCU has a negligible effect on normal expression of CYP2E1 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

CYP2E1 gene expression in BRL3A cell line treated with MCU. BRL3A cells were incubated with paracetamol and MCU at different concentrations in media containing 2% fetal bovine serum for 24 h at 37°C. RNA from cells were extracted for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction as described in materials and methods (A) CYP2E1 PCR products, (B) represents the relative level of CYP2E1 gene expression normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAPDH) RNA and values depict arbitrary units. (MCU 350) MCU 350 µg/ml, (MCU 150) MCU 150 µg/ml, (MCU 350-PA) MCU 350 µg/ml with paracetamol, (MCU 150-PA) MCU 150 µg/ml with paracetamol, (PA) paracetamol and (CTR) control. ***P < 0.001 compared with control, **P < 0.01 compared with paracetamol.

.

CYP2E1 gene expression in BRL3A cell line treated with MCU. BRL3A cells were incubated with paracetamol and MCU at different concentrations in media containing 2% fetal bovine serum for 24 h at 37°C. RNA from cells were extracted for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction as described in materials and methods (A) CYP2E1 PCR products, (B) represents the relative level of CYP2E1 gene expression normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAPDH) RNA and values depict arbitrary units. (MCU 350) MCU 350 µg/ml, (MCU 150) MCU 150 µg/ml, (MCU 350-PA) MCU 350 µg/ml with paracetamol, (MCU 150-PA) MCU 150 µg/ml with paracetamol, (PA) paracetamol and (CTR) control. ***P < 0.001 compared with control, **P < 0.01 compared with paracetamol.

Effect of MCU on hepatic markers in rats

MCU administered to female rats at doses up to 2000 mg/kg b.w did not produce any toxicity or mortality over a period of 14 days. Body weights were increased in these animals compared to their initial weights. No abnormalities were detected in the necropsy examinations. Doses of 200 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg were chosen for in vivo studies on hepatoprotective activity and Table 2 depicts shows results of hepatic markers. Administration of paracetamol after 24 hours intoxication resulted in a significant increase (P < 0.001) in AST, ALT, ALP, total bilirubin and decrease (P < 0.01) in total protein in group 2 as compared to group 1. MCU administered groups (200 and 400 mg/kg body weight), significantly blocked the elevation of serum AST, ALT, ALP, total bilirubin levels significantly (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01) as compared to group 2. Furthermore MCU also significantly increased serum protein content. Silymarin also showed better protection (P < 0.001) against the liver damage (Table 2). Thus MCU showed a comparable hepatoprotective activity to that of a marketed product.

Table 2.

In vivo hepatoprotective study in rats

|

Groups and treatment

|

AST

IU/L

|

ALT

IU/L

|

ALP

IU/L

|

TB

mg/dL

|

TP

mg/dL

|

| Group I Normal control |

83.6 ± 6.5 |

43.6 ± 4.5 |

40.08 ± 5.2 |

18.8 ± 0.30 |

5.54 ± 0.37 |

| Group II Paracetamol |

359.8 ± 12.6###

|

266.4 ± 8.9###

|

170.7 ± 5.5###

|

21.6 ± 0.40##

|

2.22 ± 0.39##

|

| Group III Silymarin (100 mg/kg, po) |

124.9 ± 8.5*** |

114.3 ± 3.89*** |

73.94 ± 7.4*** |

16.0 ± 0.36* |

4.93 ± 0.92* |

| Group IV MCU (400 mg/kg, po) |

311.7 ± 5.2** |

227.9 ± 11.5** |

139.6 ± 6.3** |

16.2 ± 0.38* |

4.89 ± 0.60* |

| Group V MCU (200 mg/kg, po) |

320.2 ± 7.5** |

237.2 ± 4.5* |

146.3 ± 5.7* |

18.1 ± 0.82 |

4.55 ± 0.95 |

Each values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Differences were considered to be statistically significant, if ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 compared with control and *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with paracetamol group. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post test. MCU, methanolic extract from C. umbellata; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; TB, total bilirubin; TP, total protein.

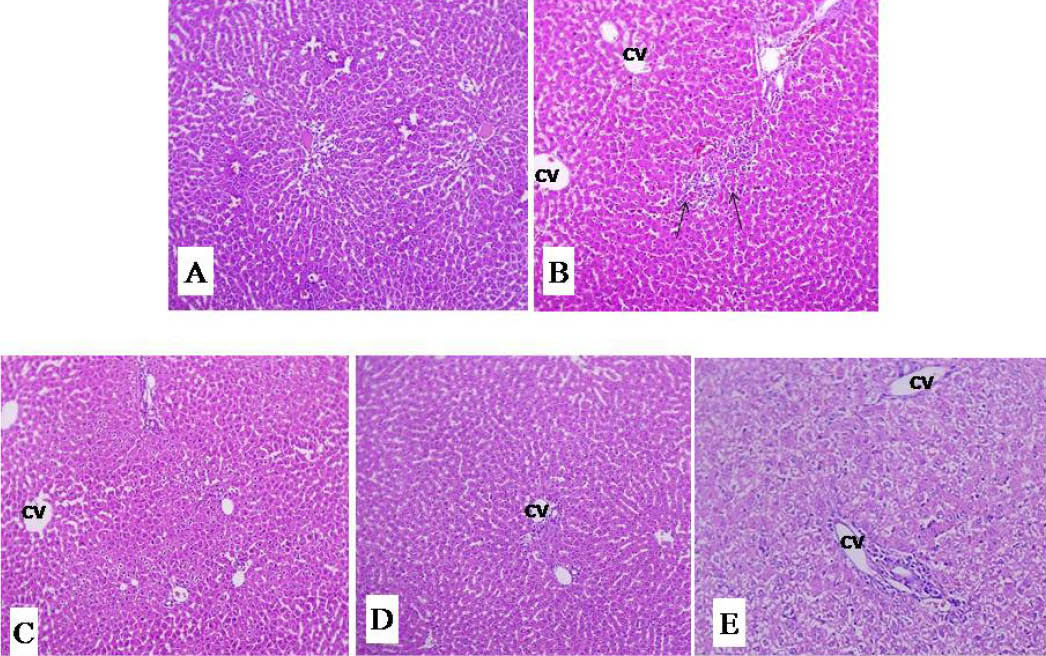

Histopathology observations

Histological observation of liver tissue in normal animal showed well-preserved architecture with intact parenchyma, central veins and sinusoids. The perivenular, periportal and midzonal hepatocytes were normal (Fig. 4A). In the paracetamol induced group, histological observation showed focally distorted architecture. Midzonal hepatocytes showed necrotic changes with moderate inflammatory infiltration. There were focal aggregates of mononuclear inflammatory cells amidst the liver parenchyma (Fig. 4B). Treatment with silymarin and MCU decreased the abnormality of liver architecture induced by paracetamol (Fig. 4C, D and E) and restored the altered histopathological changes.

Fig. 4.

Effect of MCU and silymarin on liver histopathology of paracetamol treated male wistar rats. Stain: haematoxylin eosin, magnification: 100X. (A) vehicle control group section showing normal liver architecture; (B) Paracetamol control section showing distorted structure with moderate inflammatory infiltrations (Arrow); (C) Silymarin (100mg/kg) paracetamol treated group section (almost near normal); (D,E) MCU (400 and 200 mg/kg) paracetamol treated group section shows lesser damage of hepatocytes and low index of necrosis. (CV) Central vein.

.

Effect of MCU and silymarin on liver histopathology of paracetamol treated male wistar rats. Stain: haematoxylin eosin, magnification: 100X. (A) vehicle control group section showing normal liver architecture; (B) Paracetamol control section showing distorted structure with moderate inflammatory infiltrations (Arrow); (C) Silymarin (100mg/kg) paracetamol treated group section (almost near normal); (D,E) MCU (400 and 200 mg/kg) paracetamol treated group section shows lesser damage of hepatocytes and low index of necrosis. (CV) Central vein.

Discussion

The involvement of oxidative stress has been well documented in the pathogenesis of several diseases. Oxidative stress also plays a larger role in the deleterious effect attributed to paracetamol hepatotoxicity involving CYP system. Therefore supplementation of exogenous antioxidants may normalize redox status during oxidative stress.

27

Polyphenols from plants represent potential substances which are effective ROS scavengers and metal chelators.

28

In this study, phytoconstituents such as quercetin, lupeol and β- sitosterol were identified in C. umbellata. Preliminary phytochemical analysis showed the presence of various phytoconstituents.

29

Total phenols and flavonoids were present in higher amounts in extracts correlating to their antioxidant capacity.

30

High free radical scavenging ability is regarded as high antioxidant activity.

31

MCU having better scavenging capacity which was followed to HCU and ACU. Furthermore, reducing capacity also measures the ability to donate electrons which reflects the antioxidant potential of a compound through reduction mechanism.

32

Higher reducing potential was found for MCU as similarly with scavenging potential. MCU also showed better antioxidant potential with other models tested which are also considered for antioxidant potential as with nitric oxide and lipid peroxidation.

33,34

The observed antioxidant activity of the extracts may be attributed due to the presence of phytoconstituents such as phenols, flavonoids and other constituents such as quercetin, difenakum, ethyl iso-allocholate, and β-sitosterol as reported earlier.

29

A compound with better reducing capacity will inhibit lipid peroxidation process significantly. Similar observations were recorded from our antioxidant data, where methanolic extracts having higher reducing potential possessed better lipid peroxidation inhibition potential.

35

Overall MCU showed better activity as compared to rest of other extracts, similar kind of observations from other species were recorded from Caralluma diffusa (Wight.) and Caralluma. adscendens (Roxb.).

18,36

In vitro assays such as cell-based models have gained importance in recent years due to their low cost, quick and reliability. For preliminary screening for hepatoprotection, liver cell lines such as BRL3A and HepG2 have been routinely used, since they resemble to the in vivo models.

37

The results of present study are in agreement with previous studies; we found that treatment of paracetamol caused depletion of GSH, cell damage (MDA levels) and mitochondrial dysfunction.

4,7,38

The co-treatment with MCU showed restored levels of altered parameters by protecting cell from damage. The restoration of altered GSH levels from MCU may be due to the presence of antioxidant phytoconstituents such as quercetin, β-sitosterol. Also protection from cell damage from MCU may be due to its inhibitory potential against progression of lipid peroxidation as evident from the antioxidant studies. On the other hand, cytochrome P450 (CYP450) system, especially CYP2E1 has been known to enhance the toxic damage caused by paracetamol by increasing the formation of NAPQI.

5

Treatment with paracetamol alone increased the expression of CYP2E1 by 0.6 folds followed with GSH depletion.

39

The co-treatment of MCU with paracetamol decreased the expression of CYP2E1 from 0.91 folds to 0.38 and 0.244 folds as compared to paracetamol alone at 150 µg/mL and 350 µg/mL respectively. Therefore, cytoprotection offered from MCU may also be attributed to the partial inhibition of CYP2E1 expression which in turn maintained normal GSH levels, along with combined effect of lowered ROS formation as evident from the various in vitro antioxidant potential.

In higher models such as in rats, paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity is one of the conventional model to evaluate the efficacy of plant based drugs for their liver protecting activity. Paracetamol at high dosage produces centrilobular hepatic necrosis which can be fatal. The study of hepatic markers such as AST, ALT, ALP, TB and TP have been found to be of great value in the assessment of clinical and experimental liver damage.

40

Hepatic necrosis leads to the elevated levels of serum enzymes AST and ALT which are indicative of cellular leakage and loss of functional integrity of cell membrane in the liver.

41

Pretreatment with MCU maintained the levels of AST, ALT towards normal levels suggesting an indication of stabilization plasma membrane and repair of cellular damage caused due to toxicity. On the other hand, ALP is an indicator of pathological alteration in biliary flow, whereas serum albumin furnishes liver functioning and used to chemical-induced hepatic damage.

42,43

MCU pretreated groups found to have ALP and TB levels equivalent to normal groups, suggesting the effective improvement in the secretary mechanism of hepatocytes. MCU treatment also restored the protein synthesis, since TP level will be depressed in hepatic conditions leading to defective protein biosynthesis.

44

Histopathological examinations substantiate the hepatoprotective nature of MCU. The abnormalities caused in the liver architecture due to the paracetamol treatment were mostly reversed following treatment with MCU. Similar observations have been made by Punniamurthy et al

45

and Shanmugam et al

46

for the hepatoprotective potential of C. umbellata. These studies illustrate that the C. umbellata extract help to maintain the biochemical and antioxidant parameters in liver, and they support our observations with the hepatoprotective effect of C. umbellata in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, our studies indicate that the C. umbellata extract counters against the free radicals and CYP2E modulation at the cellular level.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hepatoprotective activities of MCU may be attributed to the combined effect of antioxidant property and reduced CYP2E1 expression. These effects may be associated with the phytoconstituents present in the extract especially flavonoids and phenolic compounds. The observed hepatoprotective activity might be attributed to the synergistic activity with these constituents because the mixtures of antioxidants were more active than the individual ones. However detailed studies on phytochemical constituents present in C. umbellata are in progress in our laboratory which may further strengthen the protective nature.

Ethical approval

All studies conducted on animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (IAEC) of Radiant Research Services Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, Karnataka (Approval No: RR/IAEC/05a-2015).

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interests to be reported.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

simple

-

√ Paracetamol is known for causing liver damage and CYP2E1 is the main enzyme which produces highly reactive metabolite NAPQI causing hepatocellular damage. Previous published report suggests that C. umbellata has hepatoprotective activity.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ The study discusses the probable mechanism for the hepatoprotection, which states that the activity may be attributed to the combined effect of antioxidant property and inhibits CYP2E1 expression from C. umbellata.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the staff of Radiant Research Services Pvt Ltd, Bangalore for their support.

References

- Wlodzimirow KA, Eslami S, Abu-Hanna A, Nieuwoudt M, Chamuleau RA. Systematic review:acute liver failure:one disease, more than 40 definitions. Aliment Pharm Ther 2012; 35(11):1245-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05097.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V,

Avdekar

AB

,

Achha

SKY

. Management of acute liver failure in infants and children:Consensus statement of the pediatric gastroenterology chapter, Indian Academy of Pediatrics. Indian Pediatr 2013; 50(5):77-82. doi: 10.1007/s13312-013-0147-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chun LJ, Tong MJ, Busuttil RW, Hiatt JRM. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and acute liver failure. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009; 43(4):342-49. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818a3854 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hinson JA, Roberts DW, James LP. Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced liver necrosis. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2010; 196:369-405. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00663-0_12 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Michael SL, Pumford NR. Mayeux PR Niesman MR, Hinson JA Pretreatment of mice with macrophage in activators decreases acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and the formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Hepatol 1999; 30(1):186-95. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300104 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Knight TR, A Kurtz, Bajt ML, Hinson JA, Jaeschkae H. Vascular and hepatocellular peroxynitrite formation during acetaminophen toxicity: Role of mitochondrial oxidant stress. Toxicol Sci 2001; 62(2):212-20. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/62.2.212 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yamaura K, Shimada M, Nakayama N, Ueno K. Protective effects of goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis L) on acetaminophen induced hepatotoxicity through inhibition of CYP2E1 in rats. Phcog Res 2011; 3(4):50-5. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.89745 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari DT, Yogendra MS, Verma SK, Singh VK, Singh SS. Anti-oxidant and hepatoprotective activities of phenolic rich fraction of Seabuck thorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L) leaves. Food Chem Toxicol 2011; 49(9):2422-8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.06.061 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MG. A review of Caralluma R Br and its segregates. Bradleya 1990; 8:1-32. doi: 10.25223/brad.n8.1990.a1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Sattar E, Ahmed AA, Hegazy ME, Farag MA, Al-Yahya MA. Acylated pregnane glycosides from Caralluma russeliana. Phytochem 2007; 68(10):1459-63. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.03.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ahmad MM, Qureshi S, Shah A, Qazi NS, Rao RM, Al-Bekairi AM. Anti-inflammatory activity of Caralluma tuberculata alcoholic extract. Fitoterapia 1993; 64(4):357-60. [ Google Scholar]

- Babu KS, Malladi S, Venkata Nadh R, Rambabu SS. Evaluation of in vitro antibacterial activity of Caralluma umbellata Haw Used in Traditional Medicine by Indian Tribes. Annu Res Rev Biol 2014; 4(6):840-55. doi: 10.9734/ARRB/2014/6401 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Braca A, Bader I, Morelli R, Carpato G, Urchi C, Izza N. New pregnane glycosides from Caralluma negevensis. Tetrahedron 2002; 58(29):5837-48. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00563-X [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bader I, Braca A, Tommasi N De, Morelli I. Further constituents from Caralluma negevensis. Phytochem 2003; 62(8):1277-81. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00678-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kumar DS. A medicinal plants survey for treatment of obesity. J Pharm Res 2011; 4(3):597-600. [ Google Scholar]

- Ramesh M. Nageshwara RY, Rama KM Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity of carumbelloside-I isolated from Caralluma umbellata. J Ethnopharmacol 1999; 68(1):349-52. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00122-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Harborne JB. Phytochemical methods:A guide to modern technique of plant analysis. London: Champmann and Hall; 1998.

- Chandran R, Sajeesh T, Parimelazhagan T. Total phenolic content, anti-radical property and HPLC profiles of Caralluma diffusa (Wight) NE Br. Journal of Biologically Active Products from Nature 2014; 4(1):188-195. doi: 10.1080/22311866.2014.933082 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jinesh VK, Jaishree J, Badami S, Shyam W. Comparative evaluation of antioxidant properties of edible and non-edible leaves of Anethum graveolens Linn. Indian J Nat Prod Resour 2010; 1(2):168-73. [ Google Scholar]

- Bellamakondi P, Godavarthi A, Ibrahim M, Kulkarni S, Naik RM, Maradam S. In vitro cytotoxicity of Caralluma species by MTT and trypan blue dye exclusion. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2014; 7(2):17-9. [ Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976; 72(1):248-54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys 1959; 82(1):70-7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem 1979; 95(2):351-8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yao XM, Wang BL, Gu Y, Li Y. Effects of bicyclol on the activity and expression of CYP450 enzymes of rats after partial hepatectomy. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2011; 46(6):656-63. [ Google Scholar]

- Yoshinobu K, Masahiro T, Hiroshi H. Assay method for antihepatotoxic activity using carbon tetrachloride induced cytotoxicity in primary cultured hepatocytes. Planta Med 1983; 49(12):222-5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969855 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Banchroft JD, Stevens A, Turner DR. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. New York: Churchil Livingstone; 1996.

- Kunwar A, Priyadarsini KI. Free radicals, oxidative stress and importance of antioxidants in human health. J Hist Med Allied Sci 2011; 1(2):53-60. [ Google Scholar]

- Carlsen MH, Halvorsen BL, Holte K, Bohn SK, Dragland S, Sampson L. The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices, herbs and supplements used worldwide. Nutr J 2010; 9(3):3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jerome JJ, Kamaraj M, Nandagopalan V, Anburaja V, Thiruvengadam M. A study of phytochemical constituents in Caralluma umbellata by GC-Ms anaylsis. Int J Pharm Sci Invent 2013; 2(4):37-41. [ Google Scholar]

- Wojdyło A, Oszmianski J, Czemerys R. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem 2007; 105(3):940-9. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.038 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li W, Shan F, Sun S, Corke H, Beta T. Free radical scavenging properties and phenolic content of Chinese black-grained wheat. J Agric Food Chem 2005; 53(22):8533-6. doi: 10.1021/jf051634y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Oktay M, Gulcin I, Kufrevioglu OI. Determination of in vitro antioxidant activity of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) seed extracts. LWT-Food Sci Technol 2003; 36(2):263-71. doi: 10.1016/S0023-6438(02)00226-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2007; 87(1):315-24. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Badmus J, Adedosu T, Fatoki J, Adegbite V, Adaramoye O, Odunola O. Lipid peroxidation inhibition and anti-radical activities of some leaf fractions of Mangifera indica. Acta Pol Pharm 2011; 68(1):23-9. [ Google Scholar]

- Elena M, Conde BE, Moure A Falque E, Dominguez H. In vitro antioxidant properties of crude extracts and compounds from brown algae. Food Chem 2013; 138(2):1764-85. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.026 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tatiya AU, Kulkarni AS, Surana SJ, Bari ND. Anti-oxidant and hypolipidemic effect of Caralluma adscendens Roxb in alloxanized diabetic rats. Int J Pharm 2010; 6(4):400-6. [ Google Scholar]

- Krithika R, Mohankumar R, Verma R, Shrivastav P, Mohamad I, Gunasekaran P, Narasimhan S. Isolation, characterization and antioxidative effect of phyllanthin against CCl4- induced toxicity in HepG2 cell line. Chem Biol Interact 2009; 181(3):351-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.06.014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Francis D, Rita L. Rapid colorometric assay for cell growth and survival modifications to the tetrazolium dye procedure giving improved sensitivity and reliability. J Immunol Methods 1986; 89(2):271-7. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90368-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Yang C, Yin M. Protective effects from Houttuynia cordata aqueous extract against acetaminophen induced liver injury. Biomedicine (Taipei) 2014; 4(1):5. doi: 10.7603/s40681-014-0005-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Achliya GS, Wadodkar SG, Dorle AK. Evaluation of hepatoprotective effect of Amalkadi Ghrita against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatic damage in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2004; 90(2):229-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.037 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Drotman RB, Lawhorn GT. Serum enzymes are indicators of chemical induced liver damage. Drug Chem Toxicol 1978; 1(2):163-71. doi: 10.3109/01480547809034433 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Hill RL, Everds NE. Principles of clinical pathology for toxicology studies. In: Wallace HA, editor. Principle and Methods of Toxicology. New York: Raven Press;1989.

-

Harper HA. The functions and tests of the liver. In: Review of Physiological Chemistry. Los Altos, California: Lange Medical Publishers; 1961.

- Clawson GA. Mechanism of carbon tetrachloride hepatotoxicity. Pathol Immunopathol Res 1989; 8(2):104-12. doi: 10.1159/000157141 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Punniamurthy N, Ranganathan V, Basheer Ahamad D, Sathesh Kumar S. Hepatoprotective Activity of Caralluma umbellata in Chicken. Indian Vet J 2014; 91(12):33-35. [ Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam G, Ayyavu M, Dowlathabad MR, Thangadurai D, Ganesan S. Hepatoprotective effect of Caralluma umbellata against acetaminophen induced oxidative stress and liver damage in rat. J Pharm Res 2013; 6(3):342-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jopr.2013.03.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]