BioImpacts. 6(1):33-39.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2016.05

Original Article

Protective mechanisms of Cucumis sativus in diabetes-related modelsof oxidative stress and carbonyl stress

Himan Heidari 1, 2, Mohammad Kamalinejad 3, Maryam Noubarani 2, Mokhtar Rahmati 2, Iman Jafarian 2, Hasan Adiban 2, Mohammad Reza Eskandari 1, 2, *

Author information:

1Zanjan Metabolic Diseases Research Center, Zajan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran

2Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, School of Pharmacy, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran

3Faculty of Pharmacy, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

Oxidative stress and carbonyl stress have essential mediatory roles in the development of diabetes and its related complications through increasing free radicals production and impairing antioxidant defense systems. Different chemical and natural compounds have been suggested for decreasing such disorders associated with diabetes. The objectives of the present study were to investigate the protective effects of Cucumis sativus (C. sativus) fruit (cucumber) in oxidative and carbonyl stress models. These diabetes-related models with overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive carbonyl species (RCS) simulate conditions observed in chronic hyperglycemia.

Methods:

Cytotoxicity induced by cumene hydroperoxide (oxidative stress model) or glyoxal (carbonyl stress model) were measured and the protective effects of C. sativus were evaluated using freshly isolated rat hepatocytes.

Results:

Aqueous extract of C. sativus fruit (40 μg/mL) prevented all cytotoxicity markers in both the oxidative and carbonyl stress models including cell lysis, ROS formation, membrane lipid peroxidation, depletion of glutathione, mitochondrial membrane potential decline, lysosomal labialization, and proteolysis. The extract also protected hepatocytes from protein carbonylation induced by glyoxal. Our results indicated that C. sativus is able to prevent oxidative stress and carbonyl stress in the isolated hepatocytes.

Conclusion:

It can be concluded that C. sativus has protective effects in diabetes complications and can be considered a safe and suitable candidate for decreasing the oxidative stress and carbonyl stress that is typically observed in diabetes mellitus.

Keywords:

C. sativus

, Cucumber, Diabetes complications, Glycation, Hepatoprotection, Liver

Copyright and License Information

© 2016 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus is growing rapidly and represents a significant social and healthcare problem worldwide. This chronic disease and its related complications, including retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, and heart failure, have become one of the principal contributors of morbidity and mortality worldwide.

1,2

The global prevalence of diabetes in 2010 was estimated 285 million adults and would increase to 439 million by 2030.

3

The increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and the undesirable side effects associated with commercially available anti-diabetic drugs have led to the investigation of new medication. Dietary plants and herbal preparations have become increasingly attractive alternatives in the prevention and treatment of this progressive disease.

4

Cucumis sativus (C. sativus), commonly called cucumber is one such plant that is a member of the Cucurbitaceae family of plants and widely cultivated all over the world. It has been reported that this edible plant has anti-hyperglycemic effects in some animal models.

5-8

A common result of diabetes type 1 and type 2 is the emergence of hyperglycemia, which is typically accompanied by excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive carbonyl species (RCS), and/or defective antioxidant defense mechanisms. This indicates a key role of free radicals in the development and progression of diabetes and its pathological consequences. Overproduction of ROS and other free radicals associated with depletion of antioxidant defense systems lead to oxidative stress, which potentiates diabetes-related complications.

9

Consequently, the markers of oxidative stress such as membrane lipid peroxidation are elevated in diabetes mellitus patients.

10

Hyperglycemia also induces auto-oxidation of glucose, all of which result in the formation of free radicals. During glycation, the carbonyl group on a sugar forms a Schiff base with the amino group. This is known as a Schiff base adduct, which is a reversible intermediate. These chemical damages ultimately result in the formation of irreversible protein modifications well-known as AGEs (advanced glycation end products) and ALEs (advanced lipoxidation end products) through the Maillard reaction.

11

Carbonyl stress is defined as the accumulation of RCS and the successive protein carbonylation.

12,13

Recent therapeutic strategies have focused on inhibition of glycation and AGE formation. Divers natural and chemical compounds have been considered as the inhibitors of AGE/ALE formation.

14

Previous studies have also revealed that the liver is one of the main organs affected by diabetes and that this progressive disease may increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic liver diseases.

15-20

Based on previously published reports on anti-hyperglycemic effects of C. sativus, we planned a study evaluating the preventive effects of aqueous fruit extract of C. sativus against different cellular and sub-cellular characteristics of cumene hydroperoxide (oxidative stress model) and glyoxal (carbonyl stress model) toxicities in freshly isolated rat hepatocytes. The diabetes-related models with overproduction of ROS and RCS simulate conditions observed in chronic hyperglycemia.

11,21,22

Materials and methods

The aqueous extract preparation

C. sativus fruits were obtained from Shahriar city, Alborz province of Iran. The fruits were approved by Department of Botany, Shahid Beheshti University (Voucher number: 8025, deposited in: Herbarium of Shahid Beheshti University). The fruits were dried at room temperature and decocted in water for 30 min. The extract after filtration was concentrated to the wanted level which had honey-like viscosity. Then 2 g of final extract was placed at 60–65°C for 72 h. The extract was dispersed in distilled water at the wanted concentrations exactly before use.

23

We selected an extensive area of concentration for the fruit extract of C. sativus in our pilot study and their protective effects against cumenehydroperoxide (CHP) and glyoxal induced cytotoxicity were evaluated (data not shown). By excluding non-effective, poorly effective or toxic concentrations, a concentration of 40 μg/mL was selected.

Chemicals

Trichloroacetic acid, cumene hydroperoxide, glyoxal, collagenase (from Clostridium histolyticum), bovine serum albumin (BSA), EGTA (ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid), HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid), acridine orange, O-phthalaldehyde, 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA), and rhodamine 123 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (Taufkrichen, Germany). All other chemicals used were of the highest commercial grade available.

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 280 to 300 g were housed in ventilated plastic cages over PWI 8-16 hardwood bedding. There were 12 air changes per hour, 12 h light photoperiod (lights on at 0800 h), an environmental temperature of 21–23°C and a relative humidity of 50%–60%. The animals were fed a normal standard chow diet and given tap water ad libitum.

Isolation and Incubation of Hepatocytes

Rat hepatocytes were obtained by perfusion of the liver with collagenase. Briefly, general anesthesia was induced and the abdomens of the rats were opened. A cannula was inserted into the portal vein and buffer I and II were slowly infused at 37°C. Buffer I contained BSA and Hanks buffer substituted with EGTA, a specific calcium chelator that chelates away calcium in order to depress cell adhesion. Buffer II consisted of Hanks free of EGTA, CaCl2, and collagenase to digest collagen fibers. Then the liver was displaced, cut into small pieces, and suspended in washing buffer. Then the homogenate was filtered and the hepatocytes were suspended in Krebs–Henseleit buffer at the density of 106 cells/ml. All the processes of isolation and incubation were done under the controlled condition that is necessary for viability of the cells.

24

Aliquots of hepatocyte suspension were taken at different time points during the 3-hour incubation period.

Cell viability

The viability of isolated hepatocytes was determined by the trypan blue (0.2% w/v) exclusion test that is based on the intactness of the plasma membrane.

24

Determination of ROS formation

Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) was used to determine ROS production. Nonfluorescent DCFH-DA penetrates the cells and further converts to dichlorofluorescin (DCFH). This compound which is nonfluorescent in turn reacts with ROS and forms highly fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF). The intensity of DCF was measured and expressed as fluorescent intensity (FI) per 106 cells.

25

A Shimadzu RF5000U fluorescence spectrophotometer was used for the measurements using excitation/emission wavelengths at 500/520 nm.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Membrane lipid peroxidation was determined by the measurement of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) that stands on the reactivity of malondialdehyde, an end product of lipid peroxidation, with thiobarbituric acid to produce an adduct.

26

Beckman DU®-7 spectrophotometer was used for the measurement at 532 nm.

Determination of intracellular GSH and extracellular GSSG

A fluorometric assay was used to measure the intracellular glutathione (GSH) and extracellular oxidised glutathione (GSSG) using a spectrofluorometric method.The excitation and emission wavelengths were 350 nm and 420 nm, respectively.

27

Mitochondrial membrane potential assay

In the present study, we used a rhodamine 123 exclusion assay to detect the membrane potential of hepatocytes due to its selective accumulation and quenching in mitochondria. Loss of the membrane potential will lead to the release of dye and, consequently, the fluorescence intensity. The dye has been used to monitor mitochondrial function in living cells. Shimadzu RF5000U fluorescence spectrophotometer was used for the measurements using excitation/emission wavelengths at 490/520 nm. Our results were presented as the percentage of mitochondrial membrane potential decline (%ΔΨm) in all the test groups.

28

Lysosomal membrane integrity assay

Hepatocyte lysosomal membrane stability was determined from the redistribution of tthe fluorescent dye, acridine orange.

29

Aliquots of the cell suspension (0.5 mL), which were previously stained with acridine orange (5 µM), were separated from the incubation medium by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 1 min. The cell pellet was then resuspended in 2 mL of fresh incubation medium. This washing process was carried out twice to remove the fluorescent dye from the media. Acridine orange redistribution in the cell suspension was then measured fluorimetrically using a Shimadzu RF5000U fluorescence spectrophotometer set at 495 nm excitation and 530 nm emission wavelengths.

Measurement of proteolysis

Lysosomal-induced proteolysis was determined using a fluorescence assessment of tyrosine release.

30

The levels of tyrosine was measured using a Shimadzu RF5000U spectrophotometer, set excitation/emission wavelengths at 277/305 nm. The tyrosine contents of the hepatocyte suspensions were measured from a standard curve constructed from the established concentrations of tyrosine.

Protein carbonyl content assessment

The levels of total protein-bound carbonyl were measured by derivatising the protein carbonyl adducts with 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), which results in generation of a stable dinitrophenyl (DNP) hydrazone product. The concentration of DNPH-derivatised proteins was assessed using a molar extinction coefficient of 22,000 M−1 cm−1.

21

Statistical analysis

The homogeneity of variances was tested using Levene’s test. The results were expressed as the mean±SD of triplicate samples (n=3) using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. The results with level of significance (p<0.05) were regarded as significant.

Results

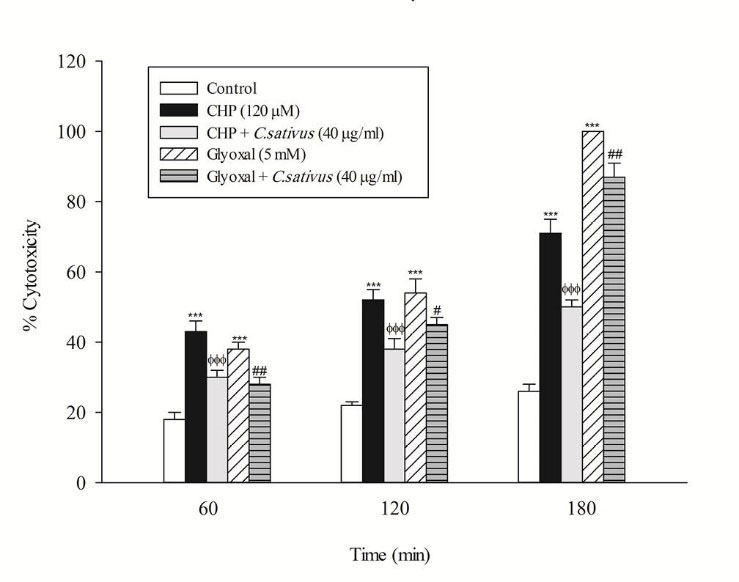

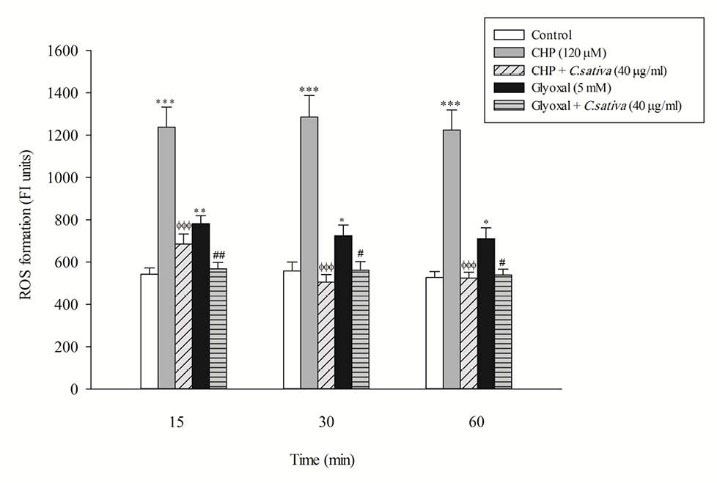

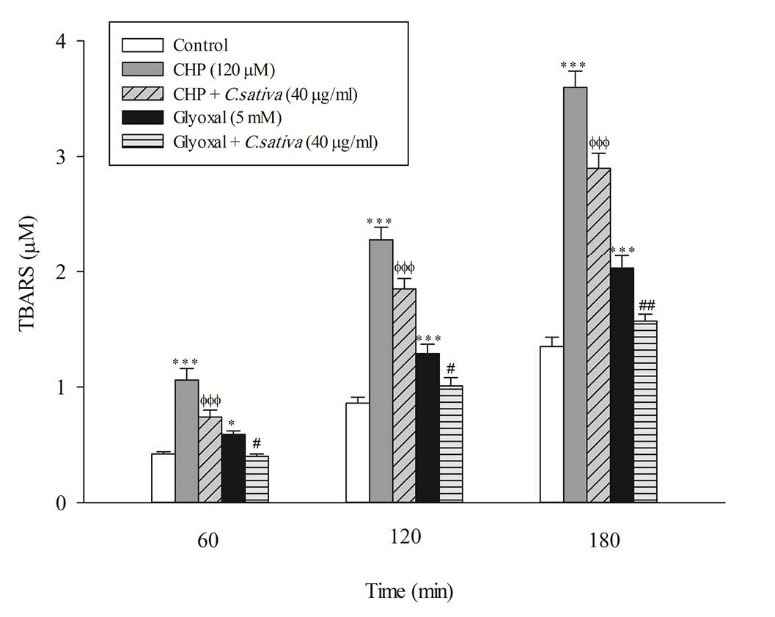

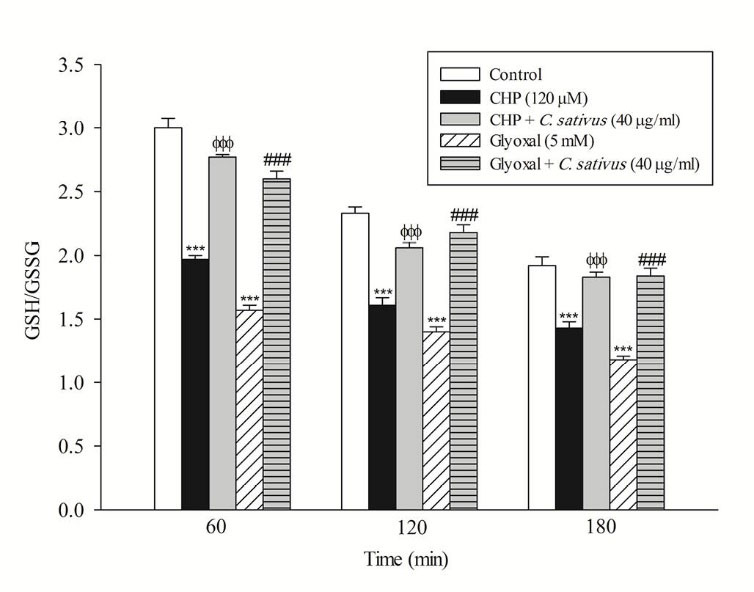

In the present study, at least 80%-90% of control hepatocytes were viable after 3 h of incubation. The C. sativus extract was added to the cells 30 min before addition of CHP and glyoxal. As indicated in Figs. 1-3, CHP and glyoxal significantly increased hepatocyte membrane lysis (cytotoxicity), ROS formation, and lipid peroxidation, respectively. Our results showed a cytoprotective effect of C. sativus (40 μg/mL) against cytotoxicity as well as ROS generation and lipid peroxidation (Figs. 1-3). Our results also revealed that after the incubation of hepatocytes with CHP and glyoxal, glutathione depletion (intracellular GSH decrease and extracellular GSSG increase) occurred as a result of ROS generation and lipid peroxidation. C. sativus (40 μg/mL) significantly prevented CHP and glyoxal induced GSH depletion (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1

.

Preventing CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte lysis by C. sativus

. Cytotoxicity was determined as the percentage of cells that take up trypan blue. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three separate experiments (n=3). *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and # p < 0.05; ## p < 0.01 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

.

Preventing CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte lysis by C. sativus

. Cytotoxicity was determined as the percentage of cells that take up trypan blue. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three separate experiments (n=3). *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and # p < 0.05; ## p < 0.01 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

Fig. 2

.

Preventing CHP and glyoxal induced ROS formation by C. sativus

.

Dichlorofluorescein (DCF) formation was expressed as fluorescent intensity units. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (n=3). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and # p < 0.05; ## p < 0.01 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

.

Preventing CHP and glyoxal induced ROS formation by C. sativus

.

Dichlorofluorescein (DCF) formation was expressed as fluorescent intensity units. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three separate experiments (n=3). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and # p < 0.05; ## p < 0.01 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

Fig. 3

.

Preventing CHP and glyoxal induced lipid peroxidation by C. sativus

.

Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) formation was expressed as μM concentrations. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three separate experiments (n=3). * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and # p < 0.05; ## p < 0.01 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

.

Preventing CHP and glyoxal induced lipid peroxidation by C. sativus

.

Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) formation was expressed as μM concentrations. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three separate experiments (n=3). * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and # p < 0.05; ## p < 0.01 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

Fig. 4

.

Effect of C. sativus on glutathione depletion (GSH/GSSG) during CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Intracellular GSH and extra cellular GSSG was flurimetrically determined. Values are presented as mean±SD (n=3). *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and ### p < 0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

.

Effect of C. sativus on glutathione depletion (GSH/GSSG) during CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Intracellular GSH and extra cellular GSSG was flurimetrically determined. Values are presented as mean±SD (n=3). *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and ### p < 0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

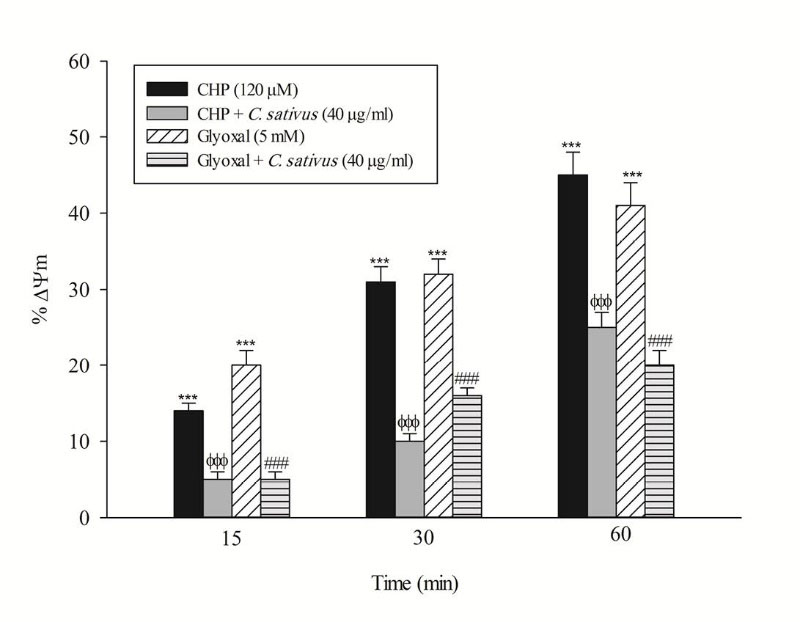

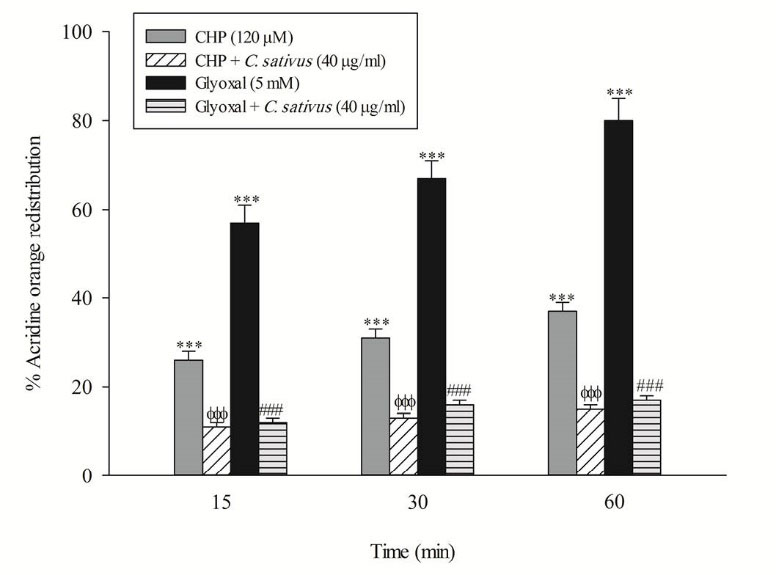

Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential is an obvious marker of mitochondrial dysfunction that rapidly decreased after CHP and glyoxal addition. Again, C. sativus (40 μg/mL) effectively prevented mitochondrial membrane potential decline in the hepatocytes (Fig. 5). In this study, acridine orange, a lysosomotropic agent, was applied for the measurement of lysosomal membrane permeabilization and damage. Our results showed that CHP and glyoxal induced a marked increase of acridine orange release into the cytosolic fraction. CHP and glyoxal induced lysosomal membrane leakiness was prevented by C. sativus (40 μg/mL) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5

.

Effect of C. sativus on mitochondrial membrane potential decline during CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Mitochondrial membrane potential was determined as the difference in mitochondrial uptake of the rhodamine 123 between control and treated cells. Our data were shown as the percentage of mitochondrial membrane potential collapse (%ΔΨm) in all treated (test) hepatocyte groups. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three separate experiments (n=3). *** p < 0.001compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and ### p < 0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

.

Effect of C. sativus on mitochondrial membrane potential decline during CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Mitochondrial membrane potential was determined as the difference in mitochondrial uptake of the rhodamine 123 between control and treated cells. Our data were shown as the percentage of mitochondrial membrane potential collapse (%ΔΨm) in all treated (test) hepatocyte groups. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three separate experiments (n=3). *** p < 0.001compared with control hepatocytes in the same time; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and ### p < 0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

Fig. 6

.

Effect ofC. sativus on lysosomal membrane damage during CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Lysosomal membrane damage was determined as difference in redistribution of acridine orange from lysosomes into cytosol between treated cells and control cells. Our data were shown as the percentage of lysosomal membrane leakiness in all treated (test) hepatocyte groups. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three separate experiments (n=3). *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and ### p < 0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

.

Effect ofC. sativus on lysosomal membrane damage during CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Lysosomal membrane damage was determined as difference in redistribution of acridine orange from lysosomes into cytosol between treated cells and control cells. Our data were shown as the percentage of lysosomal membrane leakiness in all treated (test) hepatocyte groups. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three separate experiments (n=3). *** p < 0.001 compared with control hepatocytes; ФФФ p < 0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and ### p < 0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

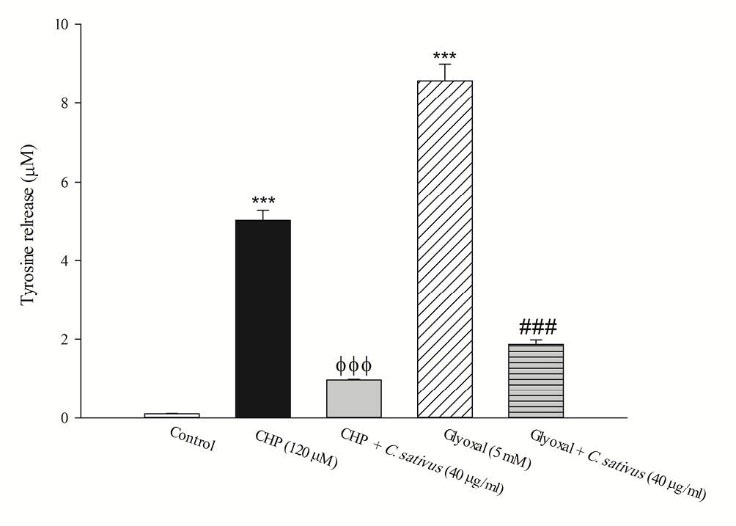

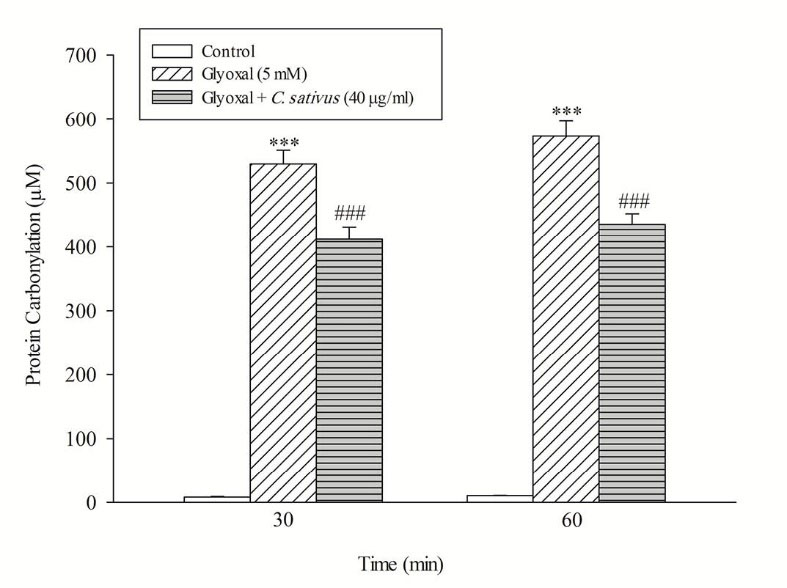

The release of the tyrosine into the extracellular medium is a marker for the cellular proteolysis. Our results revealed that when hepatocytes were incubated with CHP and glyoxal, proteolysis occurred which was prevented by C. sativus (40 μg/mL) (Fig. 7). Protein carbonylation is one of the important markers of carbonyl stress that can be promoted by ROS formation. Our results indicated that glyoxal induced protein carbonylation which was prevented by C. sativus (40 μg/mL) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7

.

Effect of

C.

sativus

on cellular proteolysis during CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Lysosomal damage induced proteolysis was determined by measuring the cellular release of tyrosine into the media after 2 h incubation with CHP and glyoxal. Values are presented as mean±SD (n=3). *** p <0.001 compared with control hepatocytes; ФФФ p <0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and ### p <0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

.

Effect of

C.

sativus

on cellular proteolysis during CHP and glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Lysosomal damage induced proteolysis was determined by measuring the cellular release of tyrosine into the media after 2 h incubation with CHP and glyoxal. Values are presented as mean±SD (n=3). *** p <0.001 compared with control hepatocytes; ФФФ p <0.001 compared with CHP treated hepatocytes and ### p <0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

Fig. 8

.

Effect of

C. sativus on protein carbonylation during glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Protein carbonylation was determined by measuring DNPH-derivatized samples. Values are presented as mean±SD (n=3). ***p <0.001 compared with control hepatocytes and ### p <0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

.

Effect of

C. sativus on protein carbonylation during glyoxal induced hepatocyte injury.

Protein carbonylation was determined by measuring DNPH-derivatized samples. Values are presented as mean±SD (n=3). ***p <0.001 compared with control hepatocytes and ### p <0.001 compared with glyoxal treated hepatocytes.

Discussion

In the present study, cytotoxicity induced by cumene hydroperoxide (oxidative stress model) or glyoxal (carbonyl stress model) was measured and the protective effects of aqueous extract of C. sativus fruit (cucumber) were evaluated in these diabetes-related models. Hyperglycemia represents the main cause of diabetes complications, and it has been demonstrated that oxidative stress and carbonylation have key roles in diabetes complications.

31

In addition, lipid peroxidation as a consequence of oxidative stress and diabetes mellitus not only initiates biomembrane disturbance but also produces a collection of reactive carbonyl compounds. Lipid peroxidation and the consequent lipoxidation-derived molecular damage of proteins plays a crucial role in the progression of diabetes complications.

32

Glutathione (GSH) is an intracellular antioxidant with reducing and nucleophilic properties that plays an essential role in cellular protection from oxidative degradation of lipids. GSH inactivates free radicals and converts to oxidized glutathione (GSSG) that can either be recovered into GSH or exported out of the cell by specialized transporters.

33

Increased intracellular GSSG is a physiological process and is therefore not a suitable feature for evaluating toxicity. This is because GSH and GSSG convert reversibly inside of cells, and elevated amounts of intracellular GSSG can be attenuated by glutathione reductase.

34

Rather, elevated extracellular GSSG is an important marker of toxicity because high intracellular concentrations of GSSG cannot be tolerated and it will be exported out of the cell. Therefore, from a toxicological standpoint, decreased intracellular GSH and increased extracellular GSSG are more suitable factors for evaluating depletion of glutathione and occurrence of oxidative stress. As shown in Figs. 1-4, C. sativus inhibited cytotoxicity, ROS formation, lipid peroxidation, and glutathione depletion in both oxidative and carbonyl stress models. These findings demonstrate that C. sativus acts as a ROS and carbonyl scavenger which can inhibit lipid peroxidation.

ROS overproduction in diabetes is the leading reason for the development and progression of diabetes-related complications. ROS attack diverse mitochondrial biomolecules, inducing mitochondrial DNA mutations and destruction of respiratory enzyme. In addition, peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) consequent to ROS production and oxidative stress causes RCS formation which plays a critical role in the aetiology and/or development of diabetes. RCS can diffuse further across biomembranes and penetrate the mitochondria, where they react with macromolecules and induce glycation damage inside the organelles.

35

Glycation of mitochondrial proteins is extremely destructive which causes mitochondrial dysfunction; so the levels of mitochondrial AGEs must be minimized in diabetic patients. Moreover, ROS and free radicals can target lysosomes and damage lipid membranes. Inside the organelle, the formation of hydroxyl radical via the Harber-Weiss reaction may destabilize the integrity of lysosomal membranes which leads to the release of proteases into the cytosol and occurrence of proteolysis and cell death.

25

As shown in Figs. 5-7, our results showed that mitochondrial membrane potential decrease, lysosomal membrane permeabilization and proteolysis were inhibited by C. sativus. Therefore, we suggest that C. sativus can be considered as a potential candidate for decreasing these sub-cellular toxic events.

Carbonylation of proteins is a permanent event that may alter function or structure of proteins and has a broad spectrum of downstream results. It has been shown that alteration of proteins has a central role in the development of chronic complications in diabetes.

13

As shown in Fig. 8, the result suggests that C. sativus acts as a cytoprotective agent in carbonyl stress by rescuing hepatocytes from protein carbonylation (Schiff base formation). Furthermore, C. sativus inhibits the Maillard reaction and subsequent AGEs/ALEs formation and accumulation.

Conclusion

Chronic hyperglycaemia provokes a cascade of events which leads to ROS and RCS formation that act as potential causative factors for tissue damage and the progression of diabetes-related complications. Our results indicated that aqueous fruit extract of C. sativus (cucumber) prevented oxidative stress and carbonyl stress in isolated rat hepatocytes. In addition, C. sativus prevented the primary stage of protein carbonylation. Considering our results and previously published data demonstrating anti-hyperglycemic effects of C. sativus, it can be suggested that cucumber is an ideal candidate for glycemic control and decreasing diabetes-related complications in diabetic patients.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards and protocols approved by the Committee of Animal Experimentation of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan-Iran (National Institutes of Health publication No 85-23, revised 1985).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

simple

-

√ Anti-hyperglycemic effects of C. sativus fruit (cucumber) have been reported but its protective effect in diabetes complications is unclear.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ C. sativus (cucumber) prevents all oxidative stress and carbonyl stress markers seen in diabetes complications.

References

- Fadini GP, Avogaro A. It is all in the blood: the multifaceted contribution of circulating progenitor cells in diabetic complications. Exp Diabetes Res 2012; 2012:742976. doi: 10.1155/2012/742976 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- White NH. Long-term Outcomes in Youths with Diabetes Mellitus. Pediatr Clin North Am 2015; 62:889-909. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.04.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010; 87:4-14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bellamakondi PK, Godavarthi A, Ibrahim M. Anti-hyperglycemic activity of Caralluma umbellata Haw. Bioimpacts 2014; 4:113-6. doi: 10.15171/bi.2014.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekar B, Mukherjee B, Mukherjee SK. Blood sugar lowering potentiality of selected Cucurbitaceae plants of Indian origin. Indian J Med Res 1989; 90:300-5. [ Google Scholar]

- Dixit Y, Kar A. Protective role of three vegetable peels in alloxan induced diabetes mellitus in male mice. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2010; 65:284-9. doi: 10.1007/s11130-010-0175-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Minaiyan M, Zolfaghari B, Kamal A. Effect of Hydroalcoholic and Buthanolic Extract of Cucumis sativus Seeds on Blood Glucose Level of Normal and Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2011; 14:436-42. [ Google Scholar]

- Roman-Ramos R, Flores-Saenz JL, Alarcon-Aguilar FJ. Anti-hyperglycemic effect of some edible plants. J Ethnopharmacol 1995; 48:25-32. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01279-M [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rezaei-Moghadam A, Mohajeri D, Rafiei B, Dizaji R, Azhdari A, Yeganehzad M. Effect of turmeric and carrot seed extracts on serum liver biomarkers and hepatic lipid peroxidation, antioxidant enzymes and total antioxidant status in rats. Bioimpacts 2012; 2:151-7. doi: 10.5681/bi.2012.020 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wright J. Effect of high-carbohydrate versus high-monounsaturated fatty acid diet on metabolic control in diabetes and hyperglycemic patients. Clin Nutr 1998; 17 Suppl 2:35-45. [ Google Scholar]

- Dong Q, Banaich MS, O’Brien PJ. Cytoprotection by almond skin extracts or catechins of hepatocyte cytotoxicity induced by hydroperoxide (oxidative stress model) versus glyoxal or methylglyoxal (carbonylation model). Chem Biol Interact 2010; 185:101-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.03.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Miyata T,

van Ypersele de Strihou

C

, Kurokawa K, Baynes JW. Alterations in nonenzymatic biochemistry in uremia: origin and significance of “carbonyl stress” in long-term uremic complications. Kidney Int 1999; 55:389-99. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00302.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aldini G, Dalle-Donne I, Facino RM, Milzani A, Carini M. Intervention strategies to inhibit protein carbonylation by lipoxidation-derived reactive carbonyls. Med Res Rev 2007; 27:817-68. doi: 10.1002/med.20073 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sullivan KA, Feldman EL. New developments in diabetic neuropathy. Curr Opin Neurol 2005; 18:586-90. [ Google Scholar]

- Byrne CD. Dorothy Hodgkin Lecture 2012: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, insulin resistance and ectopic fat: a new problem in diabetes management. Diabet Med 2012; 29:1098-107. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03732.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Wang X, Gong G, Ben Q, Qiu W, Chen Y. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cancer 2012; 130:1639-48. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26165 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB, Tran T, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004; 126:460-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.065 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y, Shimada M, Hasegawa H, Gion T, Kajiyama K, Shirabe K. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with diabetes mellitus after hepatic resection. Hepatology 1998; 27:1567-71. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270615 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Jepsen P, Watson H, Andersen PK, Vilstrup H. Diabetes as a risk factor for hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis patients. J Hepatol 2015. pii: S0168-8278(15)00470-5.

- Wang P1, Kang D, Cao W, Wang Y, Liu Z. Diabetes mellitus and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2012; 28:109-22. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1291 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Banach MS, Dong Q, O’Brien PJ. Hepatocyte cytotoxicity induced by hydroperoxide (oxidative stress model) or glyoxal (carbonylation model): prevention by bioactive nut extracts or catechins. Chem Biol Interact 2009; 178:324-31. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.10.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shahraki J, Zareh M, Kamalinejad M, Pourahmad J. Cytoprotective Effects of Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Extracts of Pistacia vera against Oxidative Versus Carbonyl Stress in Rat Hepatocytes. Iran J Pharm Res 2014; 13:1263-77. [ Google Scholar]

- Mirmohammadlu M, Hosseini SH, Esmaeili Gavgani M, Kamalinejad M, Noubarani M, Eskandari MR. Hypolipidemic, hepatoprotective and renoprotective effects of Cydonia oblonga Mill fruit in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Iran J Pharm Res 2015; 14:1207-14. [ Google Scholar]

- Maruf AA, Lip H, Wong H, O’Brien PJ. Protective effects of ferulic acid and related polyphenols against glyoxal- or methylglyoxal-induced cytotoxicity and oxidative stress in isolated rat hepatocytes. Chem Biol Interact 2015; 234:96-104. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.11.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eskandari MR, Rahmati M, Khajeamiri AR, Kobarfard F, Noubarani M, Heidari H. A new approach on methamphetamine-induced hepatotoxicity: involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction. Xenobiotica 2014; 44:70-6. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2013.807958 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Smith MT, Thor H, Hartizell P, Orrenius S. The measurement of lipid peroxidation in isolated hepatocytes. Biochem Pharmacol 1982; 31:19-26. [ Google Scholar]

- Eskandari MR, Fard JK, Hosseini MJ, Pourahmad J. Glutathione mediated reductive activation and mitochondrial dysfunction play key roles in lithium induced oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in liver. Biometals 2012; 25:863-73. doi: 10.1007/s10534-012-9552-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Andersson BS, Aw TY, Jones DP. Mitochondrial transmembrane potential and pH gradient during anoxia. Am J Physiol 1987; 252:C349-55. [ Google Scholar]

- Pourahmad J, Eskandari MR, Kaghazi A, Shaki F, Shahraki J, Fard JK. A new approach on valproic acid induced hepatotoxicity: involvement of lysosomal membrane leakiness and cellular proteolysis. Toxicol In Vitro 2012; 26:545-51. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.01.020 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Novak RF, Kharasch ED, Wendel NK. Nitrofurantoin-stimulated proteolysis in human erythrocytes: a novel index of toxic insult by nitroaromatics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1988; 247:439-44. [ Google Scholar]

- Louro TM, Matafome PN, Nunes EC, da Cunha FX, Seiça RM. Insulin and metformin may prevent renal injury in young type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2011; 653:89-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.11.029 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kumawat M, Sharma TK, Singh I, Singh N, Ghalaut VS, Vardey SK. Antioxidant Enzymes and Lipid Peroxidation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients with and without Nephropathy. N Am J Med Sci 2013; 5:213-9. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.109193 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cole SP, Deeley RG. Transport of glutathione and glutathione conjugates by MRP1. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2006; 27:438-46. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.06.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Keppler D. Export pumps for glutathione S-conjugates. Free Radic Biol Med 1999; 27:985-91. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00171-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pun PB, Murphy MP. Pathological significance of mitochondrial glycation. Int J Cell Biol 2012; 2012:843505. doi: 10.1155/2012/843505 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]