BioImpacts. 6(1):25-31.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2016.04

Original Article

A microRNA isolation method from clinical samples

Sepideh Zununi Vahed 1, 2, 3, Abolfazl Barzegari 1, 3, Yalda Rahbar Saadat 1, Somayeh Mohammadi 4, Nasser Samadi 2, 3, *

Author information:

1Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2Drug Applied Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3School of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4Department of Nutrition, Faculty of Nutrition Sciences, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

microRNAs (miRNAs) are considered to be novel molecular biomakers that could be exploited in the diagnosis and treatment of different diseases. The present study aimed to develop an efficient miRNA isolation method from different clinical specimens.

Methods:

Total RNAs were isolated by Trizol reagent followed by precipitation of the large RNAs with potassium acetate (KCH3COOH), polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000 and 6000, and lithium chloride (LiCl). Then, small RNAs were enriched and recovered from the supernatants by applying a combination of LiCl and ethanol. The efficiency of the method was evaluated through the quality, quantity, and integrity of the recovered RNAs using the A260/280 absorbance ratio, reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), and quantitative real-time PCR (q-PCR).

Results:

Comparison of different RNA isolation methods based on the precipitation of DNA and large RNAs, high miRNA recovery and PCR efficiency revealed that applying potassium acetate with final precipitation of small RNAs using 2.5 M LiCl plus ethanol can provide high yield and quality small RNAs that can be exploited for clinical purposes.

Conclusion:

The current isolation method can be applied for most clinical samples including cells, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues and even body fluids with a wide applicability in molecular biology investigations.

Keywords: Clinical samples, FFPE tissues, microRNA isolation, Q-PCR

Copyright and License Information

© 2016 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Basically, microRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of intracellular noncoding small (20–23 nt) RNAs that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by binding to the 3′ untranslated region of target mRNAs, and cause mRNA degradation or translational inhibition. miRNAs are vital regulators of numerous biological processes, including cellular proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, functional regulation of the immune system, stem cell biology, and glucose, cholesterol, and iron homeostasis.

1-4

Several studies have revealed an involvement of miRNA’s dysregulation in various important human conditions and several diseases such as viral diseases, immune related ailments,

5,6

heart diseases,

7,8

development of cancers,

9,10

neurological disorders,

11

and rejection of solid organ transplants.

12

Positioned up-stream of gene regulation cascades, their presence in tissues and body fluids

13

along with their remarkable stability make miRNAs excellent biomarkers for a wide panel of human diseases.

Different miRNA profiling platforms and techniques (e.g., cloning, microarrays, northern blots, qPCR, and nanoscale technologies) have been used to analyze the miRNAs from different cells and tissues. Given all these facts upon the pivotal role of miRNAs in human health and diseases, these important biomolecules need to be efficiently isolated from all possible biological samples. Otherwise, inefficient miRNA isolation may affect all downstream analysis and even lead to controversial results. A variety of commercial kits for the isolation of miRNAs are available; nevertheless, they are not cost-effective and different kits are needed for different clinical samples. Consequently, the development of the alternative protocols for the isolation of miRNAs from a variety of clinical samples appears to be an inevitably crucial step that can be improved through the precise understanding of material function(s) in molecular biology.

Only a few studies have offered novel methods for extracting miRNAs from clinical samples

14,15

or demonstrated the influence of different RNA isolation methods with different kits without recommending a particular method.

16,17

Mraz et al suggested an RNA isolation method using Trizol/TRI-Reagent followed by alcohol precipitation as a robust reproducible method to obtain miRNAs from B lymphocytes in blood.

18

Recently, a phenol-free method was developed for isolation of miRNA from biological fluids.

19

There is an increasing demand in biomedicine and biotechnology for the development of an efficient miRNA isolation method from a variety of biological specimens. This study explains a technique for miRNA isolation to conserve the quality and quantity of miRNAs.

Materials and methods

Solutions and reagents

RPMI1640 medium and Trypsin –EDTA (1X) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Trizol reagent were acquired from Invitrogen-Gibco (Paisley, UK). RNase inhibitor, dNTP, reverse transcriptase and SYBR green PCR Master Mix were obtained from Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany), and Applied Biosystems (Warrington, UK), respectively. Tris-HCl and DEPC water were purchased from Sinagen co. (Tehran, Iran). Red blood cells lysing buffer (RLB) was prepared by 2M Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 1M MgCl2, 3M NaCl; and 10 mM Tris-HCI (pH 8.0). Other materials were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). All solutions including 10% (w/v) PEG 4000/6000, LiCl and 3 M potassium acetate (pH 5.2) and TE buffer were prepared using DEPC water.

Sample collection

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and colon adenocarcinoma cells (HT-29) were purchased from Pasteur Institute cell bank of Iran. Urine, blood, and other body fluid samples were obtained from healthy volunteer individuals after obtaining the institutional ethical approval for the entire study. All participants were provided with a written informed consent before participating in the study. Bronchial lavage of lung cancer patients and urine specimens of kidney transplant recipients were also collected from Imam Reza Hospital, Tabriz, Iran. Moreover, three FFPE tumor tissues (colon, rectum, and stomach) were included by a licensed pathologist.

Sample preparation

A volume of 10-50 mL first morning urine specimen, 3 mL fasting blood and 0.2 mL of each body fluid including plasma, saliva, tear, urine, and bronchial lavage were processed immediately after collection.

Cell line preparation

HT-29 and HUVEC cell lines were cultured in 6 multiple well plates containing 3 mL of RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were cultured 48 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Reaching 70 to 80% confluency, the supernatant was discarded and the cells (2×) were washed with PBS.

FFPE tissue blocks deparaffination

Three FFPE biopsies were subjected to de-paraffination and miRNA isolation. Excess paraffin was trimmed off from the tissue block with a scalpel. Paraffin sections (10-50 mg) were placed into a 1.5 RNase free microtube and incubated at 60°C for 10 min for melting the paraffin. The sections were transferred into a mortar containing liquid nitrogen. Then, the frozen tissue was grinded into powder using pestle. The powdered sections were transferred into a new microtube and 1 mL of xylene was added and mixed thoroughly by vortexing 10 min at room temperature in order to extract the remaining paraffin. After centrifugation at 14,000 ×g for 2 min, the supernatant was removed and 1 mL of ethanol 100% was added to pellet and vortexed for 10 min. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 14,000 ×g for 2 min and the supernatant was cautiously poured off. This step was repeated three times by adding 1 mL of each 96%, 80%, and 70% ethanol. The centrifuged pellet was air-dried at room temperature for 10 min to remove the ethanol completely.

Plasma preparation

The peripheral blood sample was collected in EDTA vacutainer, 2 mL of which was centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 ×g at 4°C in a microtube. Plasma was transferred into another microtube without touching the leukocyte layer. One mL of RLB was added to the precipitate and mixed gently to lysis RBCs.

20

After centrifugation for 5 min at 825 ×g, the supernatant was removed. In order to isolate circulating miRNAs, the plasma was re-centrifuged at 1000 ×g, 4°C for 10 min. Plasma was collected carefully and aliquoted in 1.5 mL RNase-free tubes and freezed at −80°C immediately for future use. Body fluid samples were centrifuged at 1,000 ×g for 10 min to pellet cellular debris.

Urine cell preparation

Urine samples were centrifuged at 3,000 ×g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the remaining cell pellet was washed with 1 mL phosphate buffer saline (PBS) once and then centrifuged at 3,000 ×g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was kept for further processing.

RNA isolation protocol

Total RNA isolation

Trizol reagent (1 mL) was added to the homogenized samples and mixed well by vortexing and then incubated at room temperature for 10 min to effectively denature proteins. Chloroform (0.2 v/v) was added and mixed, by inverting the tubes, for 10 s to separate the aqueous and the organic phase. The samples were incubated 5 min at room temperature for the complete dissociation of nucleoprotein complexes. The sample was centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 12 min at 4°C. All RNAs, including small RNAs, were in the aqueous phase, which was the top clear phase.

Precipitation of large RNAs and enrichment of small RNAs

To compare precipitation efficiency of different materials, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and then divided into different tubes. Potassium acetate 3 M, pH 5.2 (1/10 v/v), equal volume of LiCl (0.4, 1, 2.5, 4, 8 and 10 M) and 10% PEG 4000 and 6000 were added and incubated in -20 and 0°C for 30 min, respectively (Fig. 1). Tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 12 min. Then the supernatant was transferred into a new tube and equal volumes of 0.4 or 2.5 M LiCl (v/v) were added to 2 volumes of precooled absolute ethanol (v/v). The samples were incubated at -80°C for 2 h and then, centrifuged at high speed 16,000 ×g, 4°C for 20 min. The pellets were dried and dissolved in 20 μL DEPC water (65°C, 5 min). Extreme drying of pellet was avoided in order to conserve its water solubility.

Quantity and quality assessment of the extracted RNAs

The RNA concentration, quantity, and purity were confirmed using the relative absorbance ratio at A260/280 and A260/230 on a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The extracted RNAs were applied for miRNA-specific reverse transcription.

miRNA-specific reverse transcription (RT)

RT method was applied to test the feasibility and quantification of the small RNA isolation protocol. RT reactions contained 2 μg of extracted RNA from cells/tissue or 4 µL of extracted RNA from body fluids, 50 nM stem-loop RT primer (Supplementary Table S1), RT buffer (1X), 2 mM of dNTPs mix, 5 U/µL MMLV reverse transcriptase and 0.25 U/µL RNase inhibitor in a volume of 20 μL. Reverse transcription was carried out at 16°C for 30 min and 42°C for 30 min, and 85°C for 5 min for the inactivation of the reaction. Moreover, reverse transcription of isolated RNAs was performed using random hexamer primer and other abovementioned agents at 25°C for 10 min and 42°C for 60 min.

Quantitative real time PCR

Q-PCR reactions were used for quantifying the expression of the RNAs on Bio-Rad iCycler iQ5 system. For qPCR, 10 μL master mix, 0.25 pM of each forward and reverse primers (Supplementary Table S1) and 1 μL cDNA, and 7 μL DEPC water were mixed to make a 20 μL reaction volume. Each sample was run in triplicate. The qPCR experiments were performed at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 25 s. After the completion of PCR cycling, melting curves were generated at 95°C to verify specificity. To generate standard curves, qPCR amplification of cDNA and their 10-1 -10-5 dilutions were carried out.

Results

This study was designed in three steps based on the flowchart represented in Fig. 1. Briefly, total RNAs were extracted by Trizol reagent. In step 1, based on our lab experiments, different concentrations of LiCl (0.4, 2.5, 4, 8 and 10 M) were applied to precipitate large RNAs and enrich small RNAs. Then small RNAs (enriched in supernatant) were precipitated by ethanol. Sediments of both large and small RNAs, obtained from this step, were analyzed by spectrophotometer and amplification of U6. Spectrophotometer analysis including the RNA yield was resulted in >200 ng/μL and A260/280 ratios exceeded 1.70, showing minimal protein contamination (Tables 1 and 2). All kinds of RNAs were precipitated when LiCl 10 M was employed since no RNA yield was detected in its supernatant. Based on the results, different LiCl concentrations were applicable in enrichment (8 M LiCl) and precipitation of small RNAs (LiCl 0.4 and 2.5 M), indicated by U6 Ct values (Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, these concentrations were employed in the second step.

Fig. 1

.

Flowchart for the RNA isolation steps.

.

Flowchart for the RNA isolation steps.

Table 1

.

Spectrophotometer analysis of large RNAs extracted from urine samples using different concentrations of LiCl

|

Isolated large RNAs with

|

RNA yield (ng/μL)

|

260/280

|

260/230

|

U6 Ct mean

|

| LiCl 10 M |

3087 ± 10 |

1.98 ± 0.02 |

1.52 ± 0.12 |

25.29 |

| LiCl 8 M |

4105 ± 4 |

1.65 ± 0.65 |

1.41 ± 0.2 |

26.46 |

| LiCl 4 M |

1487 ± 30 |

1.67 ± 0.01 |

0.53 ± 0.15 |

25.78 |

| LiCl 2.5 M |

1435 ± 2.8 |

1.91 ± 0.57 |

0.51 ± 0.13 |

21.30 |

| LiCl 0.4 M |

439 ± 8.1 |

2.18 ± 0.35 |

2 ± 0.26 |

23.80 |

| LiCl free |

1030 ± 36 |

1.65 ± 0.54 |

0.86 ± 0.62 |

25.54 |

Numbers represent the LiCl concentrations.

Table 2

.

Spectrophotometer analysis of small RNAs extracted from urine samples using different concentrations of LiCl

|

Isolated RNAs

|

RNA yield (ng/μL)

|

260/280

|

260/230

|

U6 Ct mean

|

| LiCl 10 M |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

| LiCl 8 M |

657 ± 21 |

1.43 ± 0.20 |

0.32 ± 0.01 |

25.64 |

| LiCl 4 M |

236 ± 19 |

1.75 ± 0.39 |

0.36 ± 0.9 |

24.85 |

| LiCl 2.5 M |

231 ± 5.9 |

1.84 ± 0.24 |

3.85 ± 0.45 |

22.36 |

| LiCl 0.4 M |

1382 ± 3.4 |

1.71 ± 0.37 |

0.7 ± 0.3 |

23.40 |

Numbers represent the LiCl concentrations.

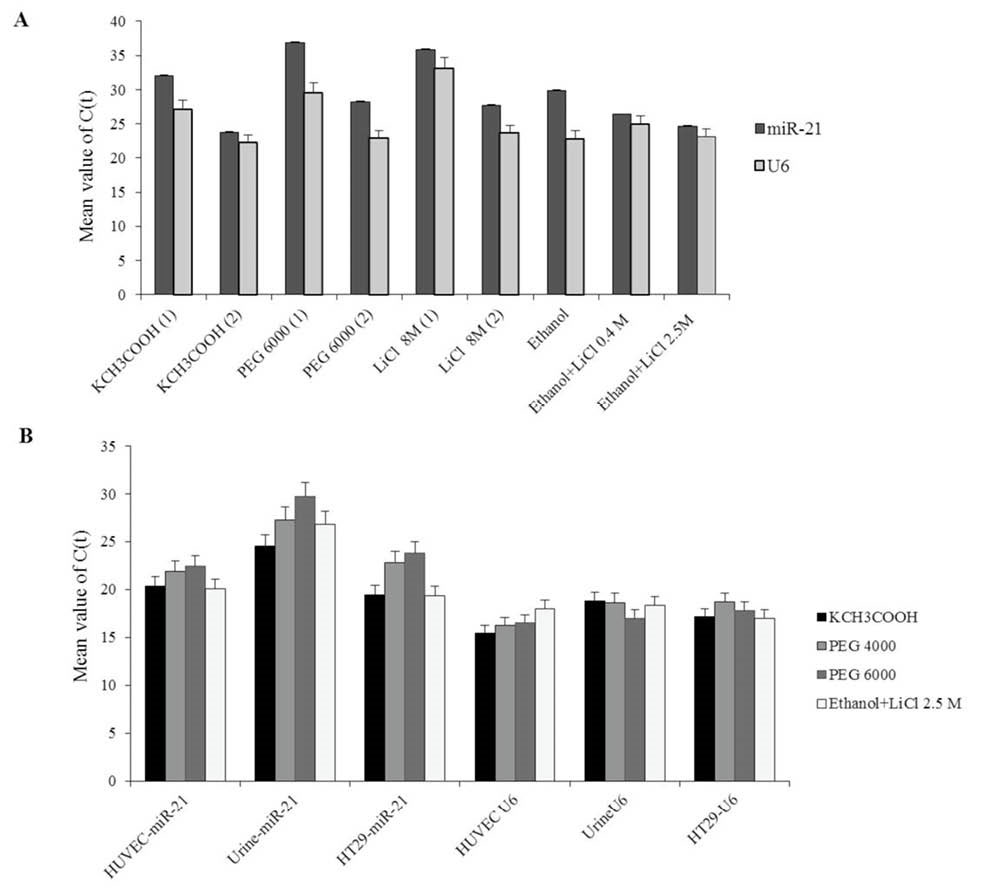

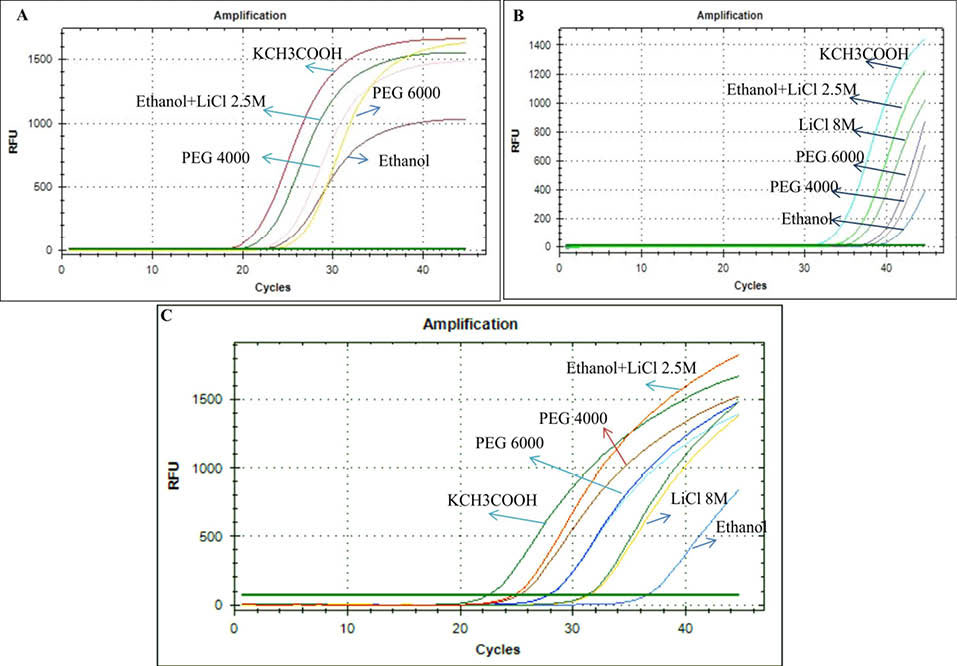

In step 2, differential precipitations of large RNAs in cells were examined with PEG 4000 and 6000, KCH3COOH and LiCl 8M using spectrophotometer (Supplementary Table S2) and q-PCR analysis (Fig. 2). The isolations were performed in triplicate. The precipitation efficiency of small RNAs (enriched in supernatant) with combination of 0.4 or 2.5 M LiCl and ethanol was compared using q-PCR (Fig. 2A). Based on the obtained results (Fig. 2A), the combination of 2.5 M LiCl and ethanol were applied for the final phase of small RNAs precipitation with different methods. Then, q-PCR amplification and PCR efficiency of the isolated small RNAs with different methods were compared (Fig. 3, Table 3). Q-PCR analysis revealed that high quantity of small RNAs was acquired when the KCH3COOH was applied (indicated by lower Ct for miR-21 and U6 and high PCR efficiency) (Table 3, Figs. 2B, 3 and 4). Addition of 2.5 M LiCl and ethanol directly after chloroform also yielded high-quality small RNAs in adequate quantities from supernatant, without applying the large RNA precipitation step (Supplementary Table S3, Fig. S1). In order to determine which method was more successful in precipitating large RNAs, quantification of two housekeeping RNAs; B-actin and 18S rRNA were done with the isolated small RNAs (Table 4). High amount of 18S rRNA was detected after applying PEG and LiCl 8M methods, indicating that these methods could not make precipitation of all kinds of large RNAs. However, after precipitation of large RNAs by KCH3COOH, small amounts of the RNAs were detected with the isolated small RNAs, indicated by higher 18S rRNA and B-actin Ct values in comparison to other methods (Table 4).

Fig. 2

.

Comparison of miR-21 and U6 expression (Ct mean values) using different methods. (A) Urine cells; P1 and P2 represent the precipitation of enriched small RNA with respectively 0.4M LiCl, and 2.5 M LiCl plus ethanol. (B) Urine, HUVEC, and HT-29 cells.

.

Comparison of miR-21 and U6 expression (Ct mean values) using different methods. (A) Urine cells; P1 and P2 represent the precipitation of enriched small RNA with respectively 0.4M LiCl, and 2.5 M LiCl plus ethanol. (B) Urine, HUVEC, and HT-29 cells.

Fig. 3

.

Q-PCR amplification plot of amplicon generated using mature miR-21 isolated from (A) TH-29 cell line, (B) plasma, and (C) urine cells with different methods.

.

Q-PCR amplification plot of amplicon generated using mature miR-21 isolated from (A) TH-29 cell line, (B) plasma, and (C) urine cells with different methods.

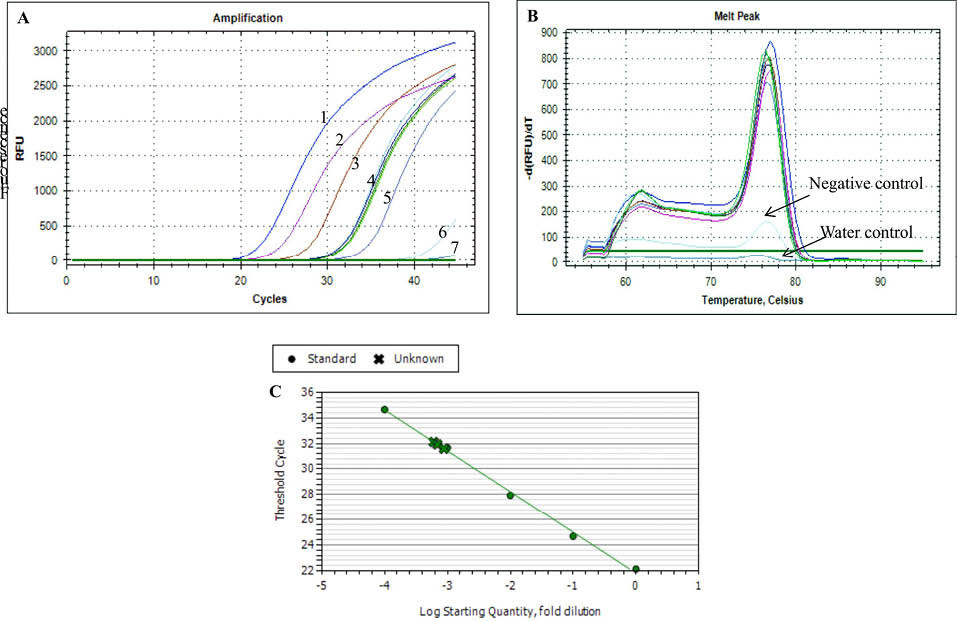

Fig. 4

.

Q-PCR amplification profiles of miR-21 using KCH3COOH method. (A) The amounts of cDNA used for q-PCR with different dilution factors as follows: 1 (1 μg); 2 (10-1 μg); 3 (10-2 μg); 4 (1010-3 μg); 5 (10-4 μg); 6 (negative control); 7 (water control). (B) Melting curve. (C) Standard plot.

.

Q-PCR amplification profiles of miR-21 using KCH3COOH method. (A) The amounts of cDNA used for q-PCR with different dilution factors as follows: 1 (1 μg); 2 (10-1 μg); 3 (10-2 μg); 4 (1010-3 μg); 5 (10-4 μg); 6 (negative control); 7 (water control). (B) Melting curve. (C) Standard plot.

Table 3

.

Quantification cycle (Ct) mean, PCR efficiency and correlation-coefficient (R2) values of miR-21 isolated from cell lines, urine, and plasma by different methods

|

Methods

|

Body fluids

|

Cell lines

|

Urine sediments

|

|

Ct

|

E (%)

|

R

2

|

Slope

|

Ct

|

E (%)

|

R

2

|

Slope

|

Ct

|

E (%)

|

R

2

|

Slope

|

|

KCH3COOH

|

31.1 ± 0.4 |

103.54 |

0.995 |

-3.24 |

17.5 ± 0.07 |

99.5 |

0.992 |

-3.33 |

23.0 ± 0.3 |

100 |

0.998 |

-3.32 |

| PEG 4000 |

33.2 ± 1.0 |

111.5 |

0.993 |

-3.074 |

20.0 ± 0.13 |

95.49 |

0.996 |

-3.44 |

25.7 ± 0.45 |

98 |

1 |

-3.37 |

| PEG 6000 |

36.8 ± 0.2 |

91.99 |

0.977 |

-3.53 |

18.3 ± 0.32 |

116 |

0.983 |

-2.99 |

28.1 ± 0.74 |

86 |

0.976 |

-3.683 |

| LiCl 8M |

34.8 ± 0.5 |

94.17 |

0.982 |

-3.47 |

21.8 ± 0.49 |

100.46 |

0.970 |

-3.31 |

31.7 ± 0.02 |

108 |

0.961 |

-3.145 |

| Ethanol+LiCl |

33.3 ± 0.07 |

99.46 |

0.994 |

-3.34 |

20.9 ± 0.9 |

105 |

0.998 |

-3.189 |

25.3 ± 0.62 |

114 |

0.993 |

-3.024 |

| Ethanol |

35.0 ± 0.09 |

120.02 |

0.979 |

-2.92 |

22.4 ± 0.03 |

98.03 |

0.991 |

-3.37 |

37.8 ± 0.63 |

105 |

0.982 |

-3.189 |

Data from 3 biological replicates of cell lines (HT-29 and HUVEC), body fluids (plasma) and urine samples.

Table 4

.

Transcripts of housekeeping genes that is available in the isolated small RNAs (after precipitation of large RNAs by different methods)

|

Methods

|

18S rRNA

|

B-actin

|

|

C(t) mean

|

C(t) SD

|

C(t) mean

|

C(t) SD

|

|

KCH3COOH

|

31.59 |

0.15 |

32.9 |

0.39 |

| PEG 4000 |

25.49 |

0.44 |

30.17 |

0.53 |

| PEG 6000 |

24.57 |

0.18 |

31.28 |

0.01 |

| LiCl 8M |

25.55 |

0.28 |

31.0 |

0.20 |

| Ethanol+2.5M LiCl |

31.98 |

0.02 |

31.18 |

0.68 |

| Ethanol |

26.47 |

0.18 |

30.65 |

0.08 |

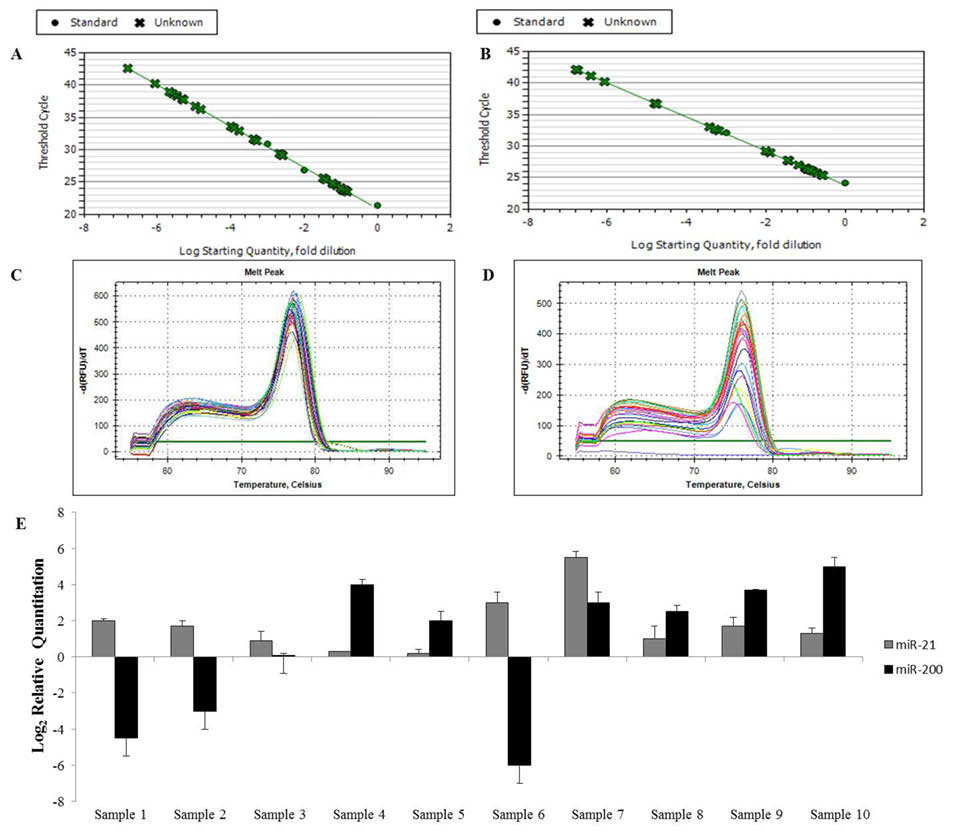

In step 3, the selected method was successfully applied for experimental validation of isolated small RNAs from several body fluids (Supplementary Table S3, Fig. S1), FFPE tissues (Supplementary Fig. S2), and urine sediments of kidney allograft patients (Fig. 5). miR-29, miR-142 and Snord47 were also evaluated in the urine samples (data were not shown).

Fig. 5

.

Validation analyses. (A, B) Standard plot and (C, D) Melting curve of miR-21 and miR-200b expression. (E) The expression levels of MiR-21 and miR-200b isolated from urine specimens of kidney allograft recipients with stable and unstable function. For gene expression analysis, threshold cycle (Ct) values were used to calculate relative expression using the ∆∆Ct method where relative expression=2-∆∆CT, and ∆∆Ct= (∆Ct of gene of interest) – (∆Ct of control).

.

Validation analyses. (A, B) Standard plot and (C, D) Melting curve of miR-21 and miR-200b expression. (E) The expression levels of MiR-21 and miR-200b isolated from urine specimens of kidney allograft recipients with stable and unstable function. For gene expression analysis, threshold cycle (Ct) values were used to calculate relative expression using the ∆∆Ct method where relative expression=2-∆∆CT, and ∆∆Ct= (∆Ct of gene of interest) – (∆Ct of control).

Discussion

Recently, a line of evidence has suggested that miRNAs can be considered as a promising candidate for the next generation of diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets since there is a strong correlation between status of disease and miRNA expression patterns.

2,9,21,22

In previous work, an advanced method was developed for the isolation of high quality genomic DNA from coniferous tissues and bacteria by applying LiCl to selectively precipitate the RNA.

23,24

In the current work, the researchers applied some modifications in the currently used mRNA isolation protocols and selected the methodology based on robustness, and finally optimized a protocol to achieve high efficient isolation system. The A260/280 absorbance ratio ranged from 1.7-2.30, indicating that isolated RNAs were relatively free of protein. Based on housekeeping gene expression results, KCH3COOH was able to precipitate large amount of RNAs, indicated by higher Ct values (Table 4). KCH3COOH is widely used in DNA extraction method; therefore, in RNA isolation, it can successfully precipitate DNA in the case of any DNA contamination.

Based on the experimental analysis, precipitation of DNA and large RNAs (Table 4), high miRNA expression (Figs. 2 and 3) and high PCR efficiency (Table 3, Fig. 4), KCH3COOH was chosen for the miRNA isolation procedure. The efficiency of enriched small RNA precipitation was compared with 0.4 or 2.5 M LiCl and ethanol. Applying LiCl in final precipitation of small RNAs was more advantageous than other RNA precipitation methods because LiCl does not precipitate DNA and protein; also eliminates inhibitors of translation or cDNA synthesis from extracted RNAs.

25,26

Final precipitation of small RNAs with 2.5 M LiCl and ethanol (rather than 0.4 M LiCl) in all methods resulted in high RNA yield and quantity (Fig. 2A).

By using KCH3COOH and final precipitation of small RNAs with 2.5 M LiCl and ethanol, all the samples showed lower Ct values that were suitable for meaningful expression analysis. As shown in Figs. 2,3 and 4, miR-21 and U6 were successfully amplified using RNAs isolated from clinical samples using the developed method. A single peak in the melting curve also confirmed the purity and specificity of the amplified PCR fragments (Fig. 4). In the developed method, the curves had correlation-coefficient (R

2

) values of 0.98± 1, detection PCR efficiency of 98-105%, slope of -3.05 to -3.50 with a single peak, indicating acceptable detection quality (Table 3, Fig. 4).

Reliable results were also obtained from body fluids and FFPE biopsies (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). Further, the protocol was validated in urine of renal allograft recipients (Fig. 5). The results indicated that the present protocol isolates respectable small RNAs suitable even for the expression analysis of circulating miRNAs besides cells and tissues specific miRNAs.

The results introduced a universal and rapid method for the isolation of high quality small RNA which can facilitate studies on gene expression in medical research. The remarkable feature of this protocol was the success in the isolation of RNA from various clinical samples especially human cells, FFPE tissues and body fluids; however, for isolation of miRNAs from each biological specimen, different isolation kits are required. We suggest that this isolation method, as a robust isolation approach, can be applied for biotechnological investigations where the quality of the miRNAs appears to be a crucial requirement.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Clinical Research, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz-Iran (Ethical codes: TBZMED.REC.1394.931 and TBZMED.REC.1394.932).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to acknowledge Drug Applied Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for financial support (Part of a PhD thesis No.: 92/4-5/6). The authors also gratefully acknowledge Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for technical support. The authors wish to express their gratitude to Dr Rabiee for his kind assistance in preparing FFPE blocks.

Supplementary materials

consists of Tables S1-S3 and Figures S1-S3.

()

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

simple

-

√ During the past decade, the discovery of microRNAs (miRNAs) has revolutionized different aspects of biomedicine.

-

√ The study of miRNAs in clinical specimens is still in its infancy era, and the technical aspects of miRNA extraction are likewise in an early stage.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ The Current method is an efficient and cost-effective small RNA extraction protocol from various clinical samples.

-

√ There is no need for different commercial kits.

-

√ This methods can be applied in molecular biology investigations.

References

- Ma L, Qu L. The function of microRNAs in renal development and pathophysiology. J Genet Genomics 2013; 40:143-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.03.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Baltimore D, Boldin MP, O’Connell RM, Rao DS, Taganov KD. MicroRNAs: new regulators of immune cell development and function. Nat Immunol 2008; 9:839-45. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.209 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004; 116:281-97. [ Google Scholar]

- Rayner KJ, Suárez Y, Dávalos A, Parathath S, Fitzgerald ML, Tamehiro N. MiR-33 contributes to the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Science 2010; 328:1570-3. doi: 10.1126/science.1189862 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pauley KM, Cha S, Chan EK. MicroRNA in autoimmunity and autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmune 2009; 32:189-94. [ Google Scholar]

- O’Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:1604-9. [ Google Scholar]

- Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature 2008; 456:980-4. doi: 10.1038/nature07511 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Carè A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med 2007; 13:613-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Iorio MV, Croce CM. MicroRNA dysregulation in cancer: diagnostics, monitoring and therapeutics A comprehensive review. EMBO Mol Med 2012; 4:143-59. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100209 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Lee C, Cho C, Fan D, Wu K, Yu J. MicroRNA dysregulation in gastric cancer: a new player enters the game. Oncogene 2010; 29:5761-71. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.352 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Zuccato C, Belyaev ND, Guest DJ, Cattaneo E, Buckley NJ. A microRNA-based gene dysregulation pathway in Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 2008; 29:438-45. [ Google Scholar]

- Amrouche L, Rabant M, Anglicheau D. MicroRNAs as biomarkers of graft outcome. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2014; 28:111-8. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2014.03.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Ochiya T. Circulating microRNA in body fluid: a new potential biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Sci 2010; 101:2087-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01650.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kowdley KV. Method for microRNA isolation from clinical serum samples. Anal Biochem 2012; 431:69-75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2012.09.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Moret I, Sánchez-Izquierdo D, Iborra M, Tortosa L, Navarro-Puche A, Nos P. Assessing an Improved Protocol for Plasma microRNA Extraction. PloS one 2013; 8:e82753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082753 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Wang W-X, Wilfred BR, Tang G. Technical variables in high-throughput miRNA expression profiling: much work remains to be done. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008; 1779:758-65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.03.012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Brunet-Vega A, Pericay C, Quilez ME, Ramirez-Lazaro MJ, Calvet X, Lario S. Variability in microRNA recovery from plasma: Comparison of five commercial kits. Anal Biochem 2015; 488:28-35. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.07.018 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mráz M, Malinova K, Mayer J, Pospisilova S. MicroRNA isolation and stability in stored RNA samples. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009; 390:1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.061 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zaporozhchenko IA, Morozkin ES, Skvortsova TE, Bryzgunova OE, Bondar AA, Loseva EM. A phenol-free method for isolation of microRNA from biological fluids. Anal Biochem 2015; 479:43-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.03.028 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shams SS, Vahed SZ, Soltanzad F, Kafil V, Barzegari A, Atashpaz S. Highly Effective DNA Extraction Method from Fresh, Frozen, Dried and Clotted Blood Samples. BioImpacts 2011; 1:183. [ Google Scholar]

- Bryant R, Pawlowski T, Catto J, Marsden G, Vessella R, Rhees B. Changes in circulating microRNA levels associated with prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 2012; 106:768-74. [ Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 2005; 435:834-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Atashpaz S, Khani S, Barzegari A, Barar J, Vahed SZ, Azarbaijani R. A robust universal method for extraction of genomic DNA from bacterial species. Microbiology 2010; 79:538-42. [ Google Scholar]

- Barzegari A, Vahed SZ, Atashpaz S, Khani S, Omidi Y. Rapid and simple methodology for isolation of high quality genomic DNA from coniferous tissues (Taxus baccata). Mol Biol Rep 2010; 37:833-7. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9634-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Mathias A, Williamson R, Gammack D. A simple method for the quantitative isolation of undegraded high molecular weight ribonucleic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1963; 13:61-6. [ Google Scholar]

- Cathala G SJ, Mendez B, West BL, Karin M, Martial JA, Baxter JD. A method for isolation of intact, translationally active ribonucleic acid. DNA 1983; 2:329-35. [ Google Scholar]