Bioimpacts. 9(2):97-103.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2019.13

Original Research

Numerical investigation of hemodynamic performance of a stent in the main branch of a coronary artery bifurcation

Seyed Esmail Razavi 1, Vahid Farhangmehr 2, *, Zahra Babaie 1

Author information:

1Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

2Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bonab, Bonab 5551761167, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

The effect of a bare-metal stent on the hemodynamics in the main branch of a coronary artery bifurcation with a particular type of stenosis was numerically investigated by the computational fluid dynamics (CFD).

Methods:

Three-dimensional idealized geometry of bifurcation was constructed in Catia modelling commercial software package. The Newtonian blood flow was assumed to be incompressible and laminar. CFD was utilized to calculate the shear stress and blood pressure distributions on the wall of main branch. In order to do the numerical simulations, a commercial software package named as COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3 was employed. Two types of stent , namely, one-part stent and two-part stent were applied to prevent the build-up and progression of the atherosclerotic plaques in the main branch.

Results:

A particular type of stenosis in the main branch was considered in this research. It occurred before and after the side branch. Moreover, it was found that the main branch with an inserted one-part stent had the smallest region with the wall shear stress (WSS) below 0.5 Pa which was the minimum WSS in the main branch without the stenosis.

Conclusion:

The use of a one-part stent in the main branch of a coronary artery bifurcation for the aforementioned type of stenosis is recommended.

Keywords: Coronary artery bifurcation, Hemodynamics, Stent, Computational fluid dynamics

Copyright and License Information

© 2019 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a leading cause of death in the developed countries based on medical reports. It is a prevalent disease of arteries in which the plaques are made up of the fatty substances such as the cholesterol and triglyceride found in the blood. Deposition of the mentioned substances on the inner wall of an artery narrows its cross-section and lowers the blood flow over the time. The consequent disorder in the normal flow of oxygen and nutrient-rich blood to some vital organs, for instance, the brain and heart, results in the sudden death. Atherosclerosis is a multifactorial disease. By identification of these factors, it is attainable to diagnose the disease and then prevent it from development. It is well addressed in the literature that the hemodynamics and the geometry of arteries play key roles in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Hemodynamics is directly related to the blood and its physical and dynamic characteristics. Age, sex, and some chronic diseases such as the obesity, diabetes, and hypertension affect these characteristics and hence, the probability of formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Males compared to females, old people compared to young ones, and people with aforementioned diseases compared to healthy ones are more susceptible to experience the atherosclerosis in their life. The role of arterial geometry in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques is independent unlike that of hemodynamics. Some arterial regions such as the bifurcation and branching regions and also the highly curved parts of arteries are favorable places for plaques to build up since the shear stress on the inner wall of arteries are lower there. These places in the coronary arteries have greater potential for the formation of plaques compared to ones in other arteries.

1-4

Having diagnosed a coronary atherosclerosis by reviewing its medical history, analyzing the results of usual blood tests, analyzing the results of diagnostic tests such as the Electrocardiogram and Echocardiogram tests, and CT scanning the heart, if the disease cannot be treated by changing the lifestyle and taking the drugs, a particular treatment such as the bypass surgery or the stent insertion is needed.

5-14

In the bypass surgery, a graft is created to bypass a blocked or narrowed coronary artery applying a vessel, cut from the other part of body. Stent is a long and thin tube (catheter) which is put into the narrowed part of a coronary artery. A wire with a deflated balloon is crossed through the catheter to the narrowed area and then, the balloon is inflated, compressing the atherosclerotic plaques and keeping the narrowed artery open.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has become a worthy tool to study the physical mechanisms which govern the formation and progression of cardiovascular atherosclerosis.

15-20

Knowing that the low or oscillatory wall shear stress (WSS) in the bifurcation or branching regions of coronary arteries or in the highly curved parts of them is the main factor in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, Malve et al employed the CFD to simulate the hemodynamics in the left main (LM) coronary bifurcation. Its geometry was captured from the CT scan images of patients without the atherosclerosis. In their work, the WSS was calculated at two risky zones of atherosclerosis, namely at the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery and at the proximal left circumflex (LC) artery, and at three sites with the high WSS concentration close to the bifurcation. Via the utilization of statistical analysis, they highlighted the relationship between the WSS and the geometric factors and found that the arterial tortuosity was crucial in detecting the sites favorable for atherosclerosis to onset and progress there

21

. Liu et al via the CFD simulated the hemodynamics in the right coronary artery (RCA) with its side branches to find a relationship between the build-up and progression of atherosclerotic plaques and the arterial curvature and the angulation of side branches.

22

Beier et al applied the CFD to simulate the hemodynamics in the non-stented and stented coronary arteries. They found that the bifurcation angle had a minor influence on the onset and progression of atherosclerosis in comparison with other bifurcation characteristics and stent insertion.

23

Chiastra et al investigated the hemodynamics in a coronary artery narrowed with a stenosis, by applying the CFD. In their numerical investigation, the geometries of artery and atherosclerotic plaques were derived from the CT scan images and the Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and constructed by SolidWorks modelling commercial software package. To find the appropriate place for the stent insertion, they did a structural analysis by Abaqus commercial software package.

24

This numerical study was conducted to investigate the effect of a bare-metal stent on the hemodynamics in the main branch of a coronary artery bifurcation for a particular type of stenosis introduced previously by Medina et al,

25

via the CFD based on the finite element method.

Geometry modeling

The coronary artery bifurcation considered here had an idealized geometry and its main and side branches had respective diameters of 2.78 mm and 2.44 mm and its bifurcation angel was 45°.

26

A bare-metal stent which is a mesh-like tube of the thin Platinum-Chromium wire, namely Omega, having the specific characteristics was used in this study.

23

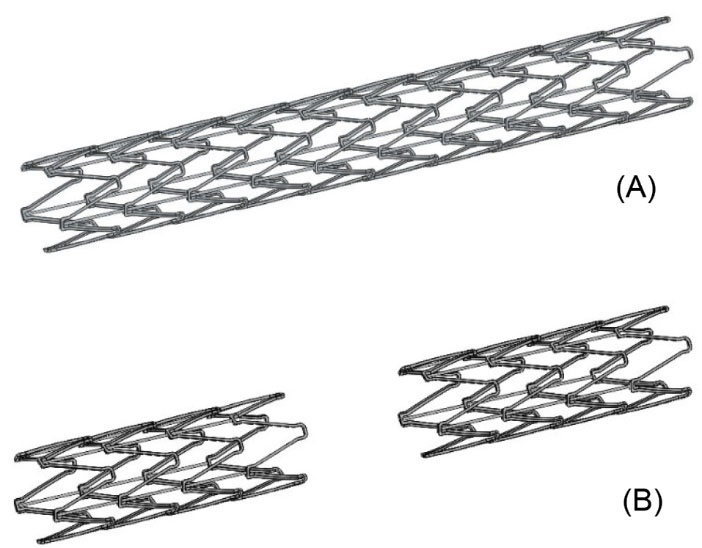

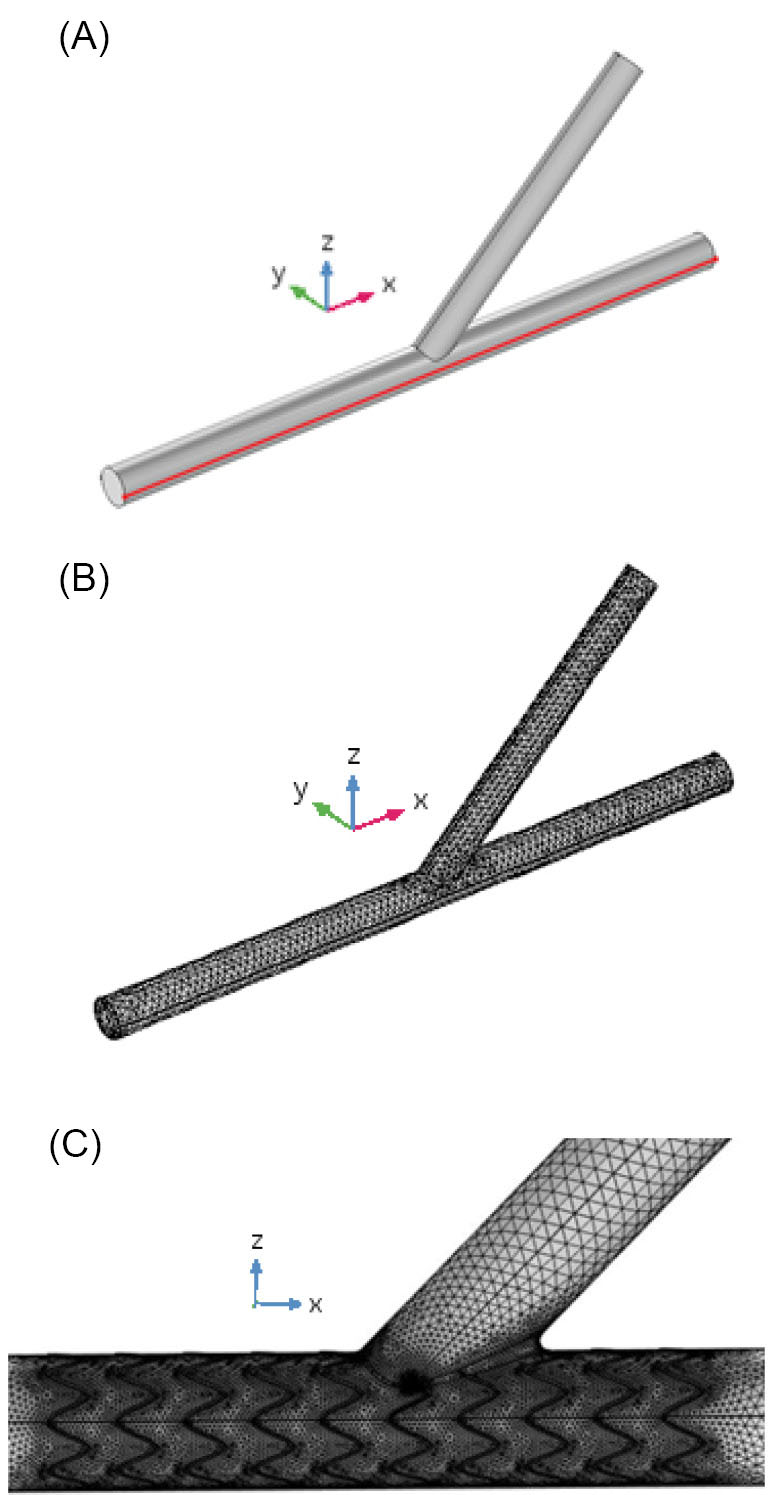

Fig. 1 schematically shows the one-part and two-part Omega stents. The three-dimensional model of the bifurcation with the inserted stent was created, employing the Catia modeling commercial software package.

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of the (A) one-part Omega stent and (B) two-part Omega stent.

.

A schematic representation of the (A) one-part Omega stent and (B) two-part Omega stent.

Governing equations and boundary conditions

Considering the blood as a Newtonian fluid,

10,15

the unsteady, laminar, three-dimensional, and incompressible governing Navier-Stokes equations were as follows:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Where x, y , z are the Cartesian coordinates, u, v, w are the corresponding velocity components, p is the blood pressure, t is the time, and ρ and μ are respectively the density and dynamic viscosity of blood chosen as 1060 kg/m3 and 0.0035 Pa.s in the present work.

27

The assumption of Newtonian blood was accurate since the arterial diameters in the bifurcation were larger than 100 μm.

28

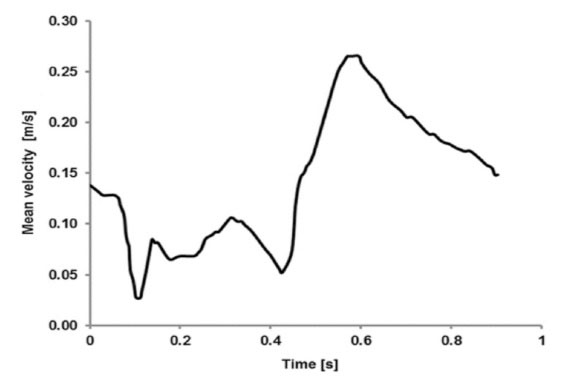

The gravity had not notable impact on the simulations. Hence, the body force term in these equations was neglected. The blood flow with a constant velocity was used at the inlet of main artery in the bifurcation. At each time, this constant velocity was extracted from the cardiac cycle illustrated in Fig. 2.

16,29

At the outlets of bifurcation, the pressure outlet boundary condition was applied.

30

The arterial walls were supposed to be rigid and thus, the no-slip boundary condition was used for them. The average volumetric flow rate and the mean velocity of blood at the inlet of main artery were respectively 60 mL/min and 0.13 m/s. Based on this mean velocity, the Reynolds number of flow in the main artery was calculated as 103, so the assumption of laminar flow in this study was acceptable. It can be comprehended from Fig. 2 that the maximum and minimum WSSs respectively belonged to t=0.6 s and t=0.1 s because at these times, the mean velocities of blood at the inlet of main artery in the bifurcation were respectively maximum and minimum.

Fig. 2.

Mean velocity of blood during a cardiac cycle, at the inlet of main artery in the bifurcation.

16

.

Mean velocity of blood during a cardiac cycle, at the inlet of main artery in the bifurcation.

16

Numerical simulation

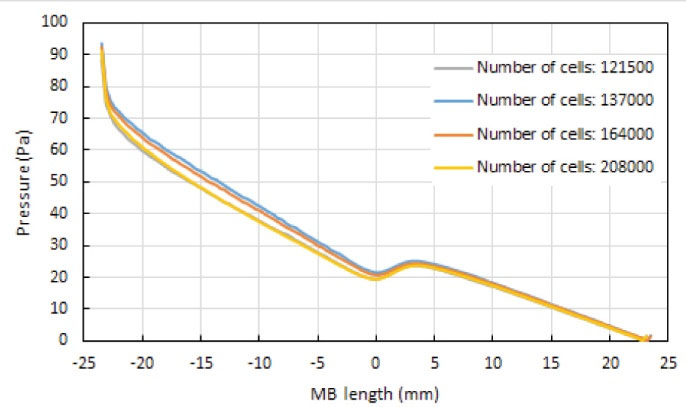

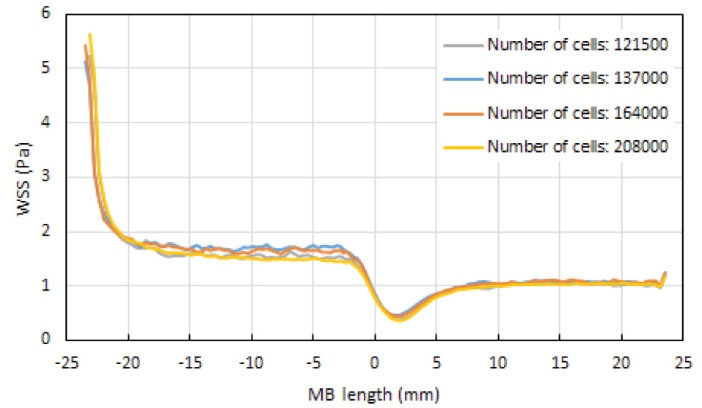

The computational domain is meshed by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3 commercial software package. Four various meshes having different densities of computational cells, namely 121 500, 137 000, 164 000, and 208 000 cells, were generated to do the mesh sensitivity analysis. Figs. 3 and 4 are respectively, the pressure and wall shear stress distributions along a specified symmetry line on the wall of the main branch in the coronary artery bifurcation, at the end of the cardiac cycle (t=0.903 s), for these meshes. This specified line was marked by the red color in Fig. 5A. It was observed that the increase in the number of cells did not considerably affect the pressure and WSS distributions. Hence, to reduce the computation time in the simulations, the first mesh with 121500 cells was used in this study. Fig. 5B represents this smooth unstructured mesh with the clustered cells in the regions with the high gradients of flow parameters. Fig. 5C shows a two-dimensional view of a selected focused part of this mesh having an inserted one-part Omega stent. The governing equations were solved by the Galerkin’s Finite Element Method in COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3. The WSS which is dependent on the blood velocity, was defined as follows:

Fig. 3.

Blood pressure distribution along the specified symmetry line marked with the red color in Fig. 5A on the wall of the healthy main branch (MB) of the coronary artery bifurcation, at t=0.903 s.

.

Blood pressure distribution along the specified symmetry line marked with the red color in Fig. 5A on the wall of the healthy main branch (MB) of the coronary artery bifurcation, at t=0.903 s.

Fig. 4.

Wall shear stress (WSS) distribution along the specified symmetry line marked with the red color in Fig. 5A on the wall of the healthy main branch (MB) of the coronary artery bifurcation, at t=0.903 s.

.

Wall shear stress (WSS) distribution along the specified symmetry line marked with the red color in Fig. 5A on the wall of the healthy main branch (MB) of the coronary artery bifurcation, at t=0.903 s.

Fig. 5.

(A) Geometry and (B) mesh generated by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3 for the coronary artery bifurcation, and (C) two-dimensional view of a selected focused part of mesh generated by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3 for the coronary artery bifurcation having a one-part Omega stent with the length of 12 mm.

.

(A) Geometry and (B) mesh generated by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3 for the coronary artery bifurcation, and (C) two-dimensional view of a selected focused part of mesh generated by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3 for the coronary artery bifurcation having a one-part Omega stent with the length of 12 mm.

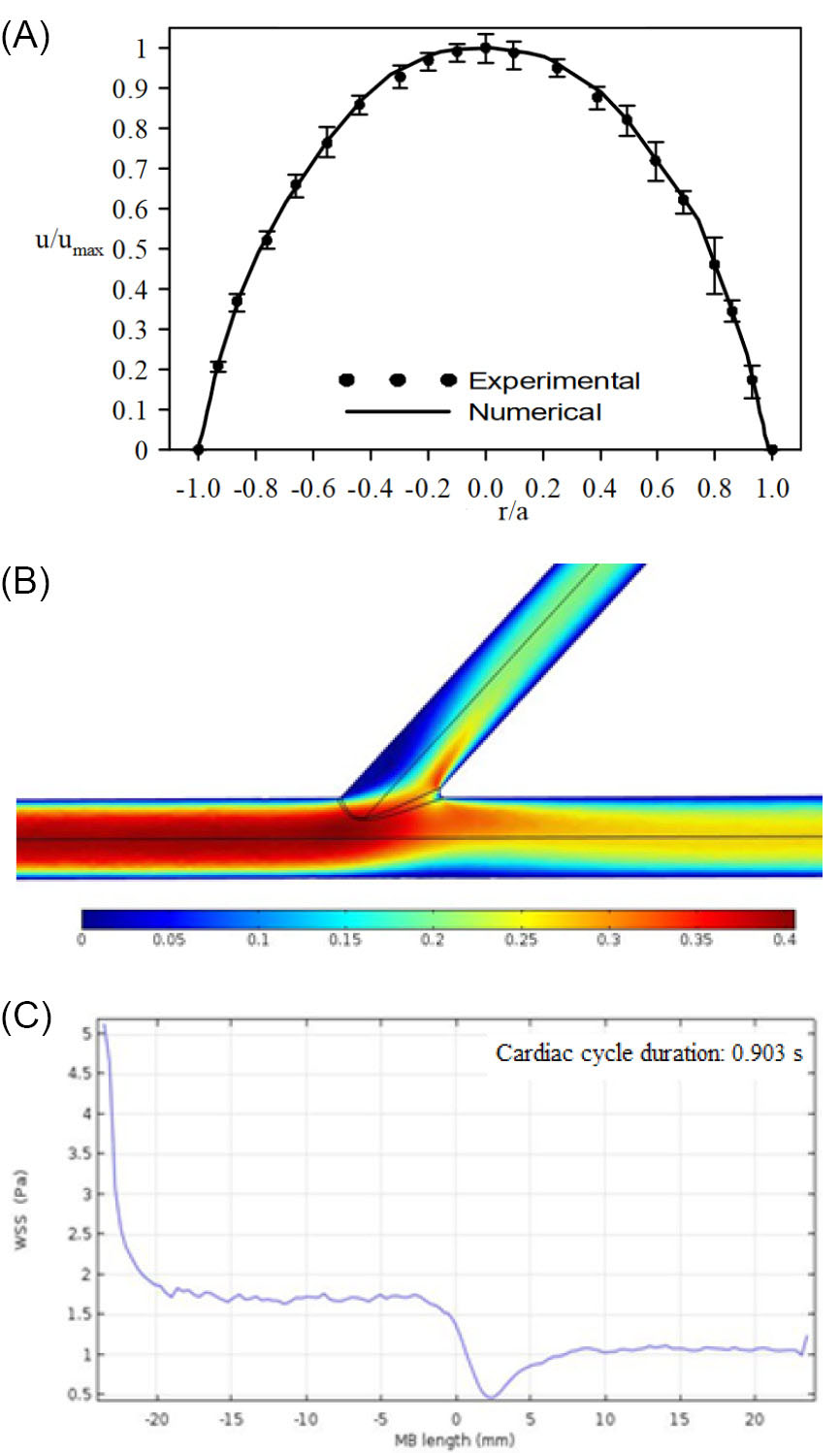

Fig. 6.

(A) Velocity profile of blood captured numerically inside a rigid tube in comparison with the experimental data,

31

(Re=260; a: the radius of tube; umax: the maximum axial velocity). (B) Velocity contour of blood (in m/s) in the healthy coronary artery bifurcation, at t=0.587 s. (C) Wall shear stress (WSS) distribution along the red line (see Fig. 5A) on the wall of the main branch (MB) of the healthy coronary artery bifurcation, at t=0.587 s.

.

(A) Velocity profile of blood captured numerically inside a rigid tube in comparison with the experimental data,

31

(Re=260; a: the radius of tube; umax: the maximum axial velocity). (B) Velocity contour of blood (in m/s) in the healthy coronary artery bifurcation, at t=0.587 s. (C) Wall shear stress (WSS) distribution along the red line (see Fig. 5A) on the wall of the main branch (MB) of the healthy coronary artery bifurcation, at t=0.587 s.

Where V is the velocity of blood and n is the direction normal to the blood flow direction

Results and Discussion

Low WSS played the main role in the formation and progression of atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary artery bifurcations. Via increasing the WSS, it was possible to prevent the onset and development of atherosclerosis in them.

17

In order to validate our numerical study, the steady, two-dimensional, laminar, and fully developed flow of the Newtonian blood in a rigid circular tube was first simulated and the results were compared to that of the experimental data.

31

The Reynolds number was 260. Fig. 6A illustrates a good agreement between the velocity profile within the tube obtained numerically and the experimental data. After the validation test, the results of our simulations of a coronary artery bifurcation were presented. Figs. 6B and 6C depict the velocity contour of blood and the WSS distribution along the red line (see Fig. 5A) on the wall of the main branch of the healthy coronary artery bifurcation.

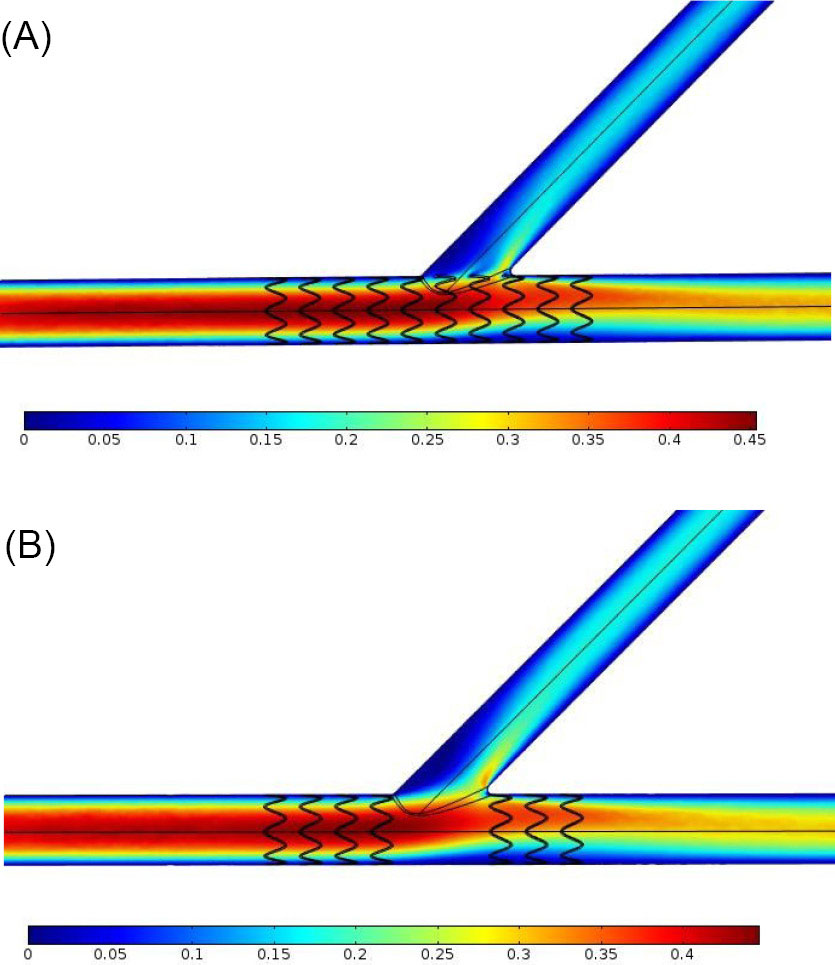

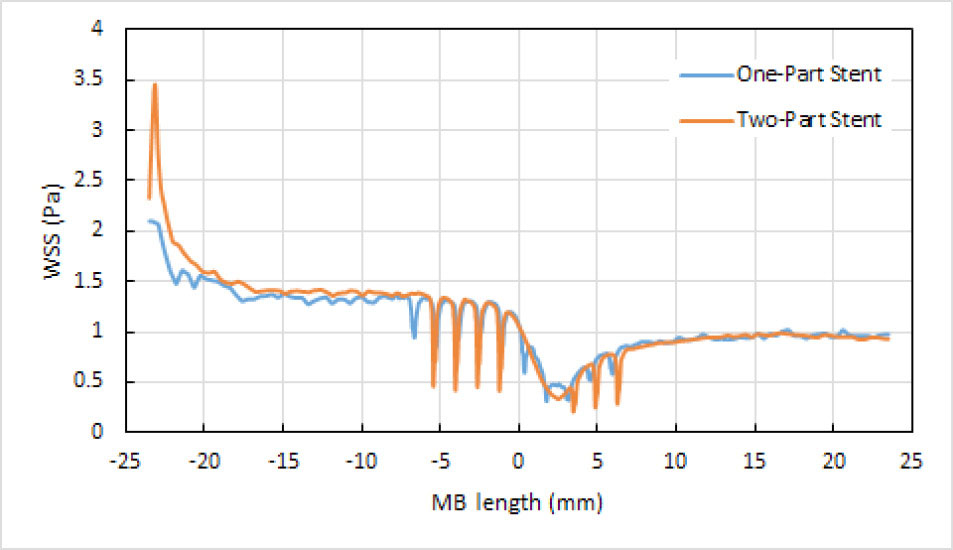

Stent insertion in the narrowed coronary artery bifurcation is an approach to increase the WSS. Two options were possible to place a stent in the main branch of a coronary artery bifurcation, having the stenosis before and after the side branch, namely, a one-part stent or a two-part stent, but it remained as a question which one was preferable regarding to their impact on the WSS. To answer this fundamental question, the numerical simulations were conducted in this investigation. Figs. 7A and 7B respectively show the velocity contour of blood in the bifurcation which has a one-part Omega stent and a two-part Omega stent in its main branch, at t=0.587 s. Fig. 8 depicts the WSS distributions along the red line (see Fig. 5A) on the wall of main branch which has the aforementioned stents, at t=0.587 s. By carefully focusing on Fig. 8 comparing with Fig. 6C, it is obviously observed that the main branch has smaller regions with the WSS below 0.5 Pa, in the case of one-part Omega stent. 0.5 Pa is the minimum WSS in the main branch without the stenosis.

10,20

Hence, it was concluded that the application of one-part Omega stent was preferable. The comparison between Figs. 7A-7B and Fig. 6B shows that the stent did not notably disturb the flow patterns except for the regions near the stent where the little oscillations in the flow patterns can be seen.

Fig. 7.

(A) Velocity contour of blood (in m/s) in the coronary artery bifurcation with a one-part Omega stent in its main branch having the stenosis before and after the side branch, at t=0.587 s. (B) Velocity contour of blood (in m/s) in the coronary artery bifurcation with a two-part Omega stent in its main branch having the stenosis before and after the side branch, at t=0.587 s.

.

(A) Velocity contour of blood (in m/s) in the coronary artery bifurcation with a one-part Omega stent in its main branch having the stenosis before and after the side branch, at t=0.587 s. (B) Velocity contour of blood (in m/s) in the coronary artery bifurcation with a two-part Omega stent in its main branch having the stenosis before and after the side branch, at t=0.587 s.

Fig. 8.

Wall Shear Stress (WSS) distribution along the red line (see Fig. 5A) on the wall of the main branch (MB) of the coronary artery bifurcation, having a one-part Omega stent or a two-part Omega stent, at t=0.587 s.

.

Wall Shear Stress (WSS) distribution along the red line (see Fig. 5A) on the wall of the main branch (MB) of the coronary artery bifurcation, having a one-part Omega stent or a two-part Omega stent, at t=0.587 s.

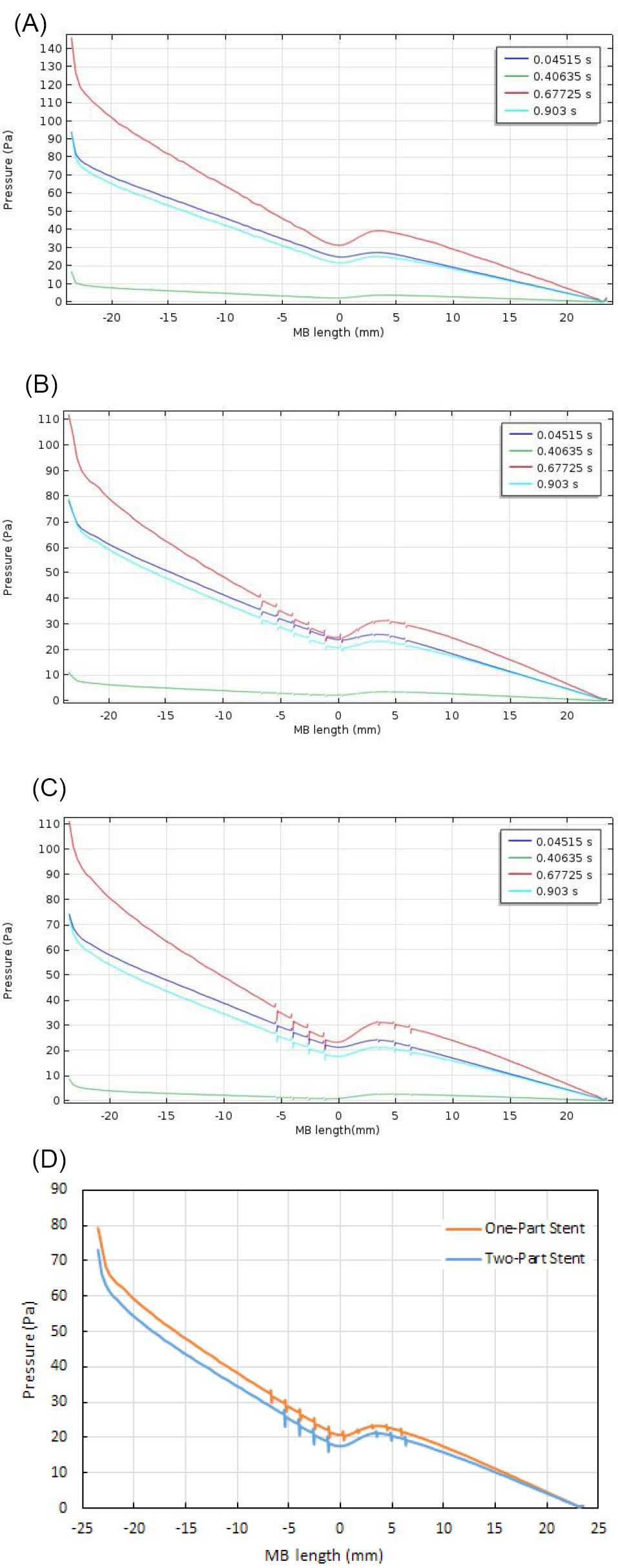

Fig. 9A to 9C respectively show the blood pressure distributions along the red line (see Fig. 5A), at four different times of the cardiac cycle. In Fig. 9A, the main branch does not have stenosis but in Figs. 9B and 9C, it has the stenosis and respectively, has a one-part Omega stent and a two-part Omega stent. It is clearly seen that the stent leads to a minor change in the pressure distributions but it causes the discontinuities in them. Fig. 9D depicts the blood pressure distribution along the red line, in the presence of a one-part Omega stent or a two-part Omega stent, at t=0.587s. It is seen that the main branch experiences a greater pressure on its wall in the presence of a one-part stent. This greater pressure has a positive performance in keeping the narrowed main branch open.

Fig. 9.

(A) Blood pressure distributions along the red line (see Fig. 5A) in the case of healthy main branch, at four different times of the cardiac cycle. (B) Blood pressure distributions along the red line (see Fig 5A) in the case of main branch with a one-part Omega stent, at four different times of the cardiac cycle. (C) Blood pressure distributions along the red line (see Fig 5A) in the case of main branch with a two-part Omega stent, at four different times of the cardiac cycle. (D) Blood pressure distribution along the red line (see Fig. 5A) in the cases of main branch with a one-part Omega stent or a two-part Omega stent, at t=0.587 s.

.

(A) Blood pressure distributions along the red line (see Fig. 5A) in the case of healthy main branch, at four different times of the cardiac cycle. (B) Blood pressure distributions along the red line (see Fig 5A) in the case of main branch with a one-part Omega stent, at four different times of the cardiac cycle. (C) Blood pressure distributions along the red line (see Fig 5A) in the case of main branch with a two-part Omega stent, at four different times of the cardiac cycle. (D) Blood pressure distribution along the red line (see Fig. 5A) in the cases of main branch with a one-part Omega stent or a two-part Omega stent, at t=0.587 s.

Limitations

There were some limitations in this numerical research. First, the geometry of coronary artery bifurcation was considered to be idealized and was not constructed from the patient-specific medical images. Second, the atherosclerotic plaques were not considered in this geometry. Third, the arterial walls were assumed to be rigid. This assumption seems to be logical.

18

In the end, it should be noted that the stenting is a complex process because the hemodynamics is greatly changed by the arterial geometric characteristics, stent type, and stent deployment. It means that the results of CFD simulations should be analyzed in-vivo.

Conclusion

CFD simulations of a stented and non-stented healthy coronary artery bifurcation for a particular type of stenosis in its main branch were presented in this paper. For the stenosis in the main branch occurred before and after the side branch, both the one-part and two-part Omega stents were modeled. Results including the WSS and the blood pressure on the wall of the main branch and the velocity contour in the bifurcation were obtained. It was found that the one-part Omega stent provided the smallest region on the wall of main branch with the shear stress below 0.5 Pa (the minimum shear stress on the wall of main branch without the stenosis). Therefore, this stent is recommended to be used in the aforementioned type of stenosis in the main branch of the coronary artery bifurcation.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

None to be declared.

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interests to be reported.

Authors contribution

SER: Project administration. VF: Technical advisor, data validating. ZB: Numerical simulation, data analysis.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

simple

-

√ The build-up and progression of atherosclerotic plaques

in the regions of a coronary artery bifurcation with the low

WSS.

-

√ The insertion of a bare-metal stent in a coronary artery

bifurcation with the stenosis to increase the WSS.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ The employment of Computational Fluid Dynamics to

numerically study the hemodynamics in the main branch of

a coronary artery bifurcation.

-

√ The recommendation of a one-part bare-metal stent for a

particular stenosis in the main branch of a coronary artery

bifurcation.

References

- Gijsen FJH, Wentzel JJ, Thury A, Lamers B, Schuurbiers JCH, Serruys PW, van der Steen AF. A new imaging technique to study 3-D plaque and shear stress distribution in human coronary artery bifurcations in vivo. J Biomech 2007; 40(11):2349-2357. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.12.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chatzizisis YS, Jonas M, Coskun AU, Beigel R, Stone BV, Maynard C. Prediction of the localization of high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques on the basis of low endothelial shear stress: an intravascular ultrasound and histopathology natural history study. Circulation 2008; 117(8):993-1002. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.695254 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- van der Giessen AG, Wentzel JJ, Meijboom WB, Mollet NR, van der Steen AF, van de Vosse FN. Plaque and shear stress distribution in human coronary bifurcations: a multi-slice computed tomography study. EuroIntervention 2009; 4:654-61. [ Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Canton G, Yuan C, Ferguson M, Hatsukami TS, Tang D. Advanced human carotid plaque progression correlates positively with flow shear stress using follow-up scan data: an in vivo MRI multi-patient 3D FSI study. J Biomech 2010; 43(13):2530-2538. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.05.018 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Razavi SE, Zanbouri R, Arjmandi-Tash O. Simulation of blood flow coronary artery with consecutive stenosis and coronary-coronary bypass. BioImpacts 2011; 1(2):99-104. doi: 10.5681/bi.2011.013 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vimmr J, Jonášová A, Bublík O. Effects of three geometrical parameters on pulsatile blood flow in complete idealised coronary bypasses. Comput Fluids 2012; 69:147-171. doi: 10.1016/j.compfluid.2012.08.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bernad SI, Totorean AF, Vekas L. Particles deposition induced by the magnetic field in the coronary bypass graft model. J Magn Magn Mater 2016; 401:269-286. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2015.10.020 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guerciotti B, Vergara Ch, Ippolito S, Quarteroni A, Antona C, Scrofani R. A computational fluid–structure interaction analysis of coronary Y-grafts. Med Eng Phys 2017; 47:117-127. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2017.05.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kramer R, Morton JR, Groom RC, Robaczewski DL. Coronary artery bypass grafting. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences, Encyclopedia of Cardiovascular Research and Medicine 2018:700-729.

- Mejia J, Mongrain R, Bertrand OF. Accurate prediction of wall shear stress in a stented artery: Newtonian versus non-Newtonian models. J Biomech Eng 2011; 133(7):074501. doi: 10.1115/1.4004408 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hsiao HM, Chiu Y-H, Lee KH, Lin CH. Computational modeling of effects of intravascular stent design on key mechanical and hemodynamic behavior. Comput Aided Des 2012; 44(8):757-765. doi: 10.1016/j.cad.2012.03.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Morlacchi S, Colleoni SG, Cardenes R, Chiastra C, Diez JL, Larrabide I. Patient-specific simulations of stenting procedures in coronary bifurcations: two clinical cases. Med Eng Phys 2013; 35(9):1272-1281. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2013.01.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rikhtegar F, Wyss C, Stok KS, Poulikakos D, Muller R, Kurtcuoglu V. Hemodynamics in coronary arteries with overlapping stents. J Biomech 2014; 47(2):505-511. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.10.048 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Beier S, Ormiston J, Webster M, Cater J, Norris S, Medrano-Gracia P, Young A, Cowan B. Hemodynamics in idealized stented coronary arteries: important stent design considerations. Ann Biomed Eng 2016; 44(2):315-329. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1387-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chaichana T, Sun Z, Jewkes J. Computation of hemodynamics in the left coronary artery with variable angulations. J Biomech 2011; 44(10):1869-1878. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.04.033 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chiastra C, Morlacchi S, Pereira S, Dubini G, Migliavacca F. Computational fluid dynamics of stented coronary bifurcations studied with a hybrid discretization method. Eur J Mech B Fluids 2012; 35:76-84. doi: 10.1016/j.euromechflu.2012.01.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dolan JM, Kolega J, Meng H. High wall shear stress and spatial gradients in vascular pathology: a review. Ann Biomed Eng 2013; 41(7):1411-1427. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0695-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chiastra C, Migliavacca F, Martínez MA, Malve M. On the necessity of modelling fluid–structure interaction for stented coronary arteries. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2014; 34:217-230. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.02.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Frattolin J, Zarandi MM, Pagiatakis C, Bertrand OF, Mongrain R. Numerical study of stenotic side branch hemodynamics in true bifurcation lesions. Comput Biol Med 2015; 57:130-138. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2014.11.014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pinto S, Campos J. Numerical study of wall shear stress-based descriptors in the human left coronary artery. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng 2016; 19(13):1443-1455. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2016.1149575 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Malvè M, Gharib AM, Yazdani SK, Finet G, Martínez MA, Pettigrew R, Ohayon J. Tortuosity of coronary bifurcation as a potential local risk factor for atherosclerosis: CFD steady state study based on in vivo dynamic CT measurements. Ann Biomed Eng 2015; 43(1):82-93. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1056-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Wu J, Ghista DN, Huang W, Wong KKL. Hemodynamic characterization of transient blood flow in right coronary arteries with varying curvature and side-branch bifurcation angles. Comput Biol Med 2015; 64:117-126. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.06.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Beier S, Ormiston J, Webster M, Cater J, Norris S, Medrano-Gracia P, Young A, Cowan B. Impact of bifurcation angle and other anatomical characteristics on blood flow–A computational study of non-stented and stented coronary arteries. J Biomech 2016; 49(9):1570-1582. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.03.038 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chiastra C, Wu W, Dickerhoff B, Aleiou A, Dubini G, Otake H, Migliavacca F, LaDisa JF. Computational replication of the patient-specific stenting procedure for coronary artery bifurcations: From OCT and CT imaging to structural and hemodynamics analyses. J Biomech 2016; 49(11):2102-2111. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.11.024 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Medina A, de Lezo JS, Pan M. A new classification of coronary bifurcation lesions. Rev Esp Cardiol 2006; 59(02):183-183. doi: 10.1016/S1885-5857(06)60130-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gastaldi D, Morlacchi S, Nichetti R, Capelli C, Dubini G, Petrini L, Migliavacca F. Modelling of the provisional side-branch stenting approach for the treatment of atherosclerotic coronary bifurcations: effects of stent positioning. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 2010; 9(5):551-561. doi: 10.1007/s10237-010-0196-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Benard N, Perrault R, Coisne D. Computational approach to estimating the effects of blood properties on changes in intra-stent flow. Ann Biomed Eng 2006; 34(8):1259-1271. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9123-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Kitajima H, Yoganathan AP. Blood flow-The basics of the discipline, ventricular function and blood flow in congenital heart disease. Blackwell Publishing; 2007.

- Davies JE, Whinnett ZI, Francis DP, Manisty CH, Aguado-Sierra J, Willson K. Evidence of a dominant backward-propagating “suction” wave responsible for diastolic coronary filling in humans, attenuated in left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 2006; 113:1768-1778. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.603050 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wellnhofer E, Osman J, Kertzscher U, Affeld K, Fleck E, Goubergrits L. Flow simulation studies in coronary arteries-impact of side-branches. Atherosclerosis 2010; 213(2):475-481. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.09.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gijsen Gijsen, FJ FJ, van de Vosse FN, Janssen J. The influence of the non-Newtonian properties of blood on the flow in large arteries: steady flow in a carotid bifurcation model. J Biomech 1999; 32(6):601-608. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00015-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]