BioImpacts. 10(1):55-61.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2020.07

Original Research

Role of the Kölliker-Fuse nucleus in cardiovascular responses to hypoxia and baroreceptor activation in anesthetized rats

Nafiseh Mirzaei-Damabi  , Bahar Rostami , Masoumeh Hatam *

, Bahar Rostami , Masoumeh Hatam *

Author information:

Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction: Parabrachial Kölliker-Fuse (KF) complex, located in dorsolateral part of the pons, is involved in the respiratory control, however, its role in the baroreflex and chemoreflex responses has not been established yet. This study was performed to test the contribution of the KF to chemoreflex and baroreflex and the effect of microinjection of a reversible synaptic blocker (Cocl2) into the KF in urethane anesthetized rats.

Methods: Activation of chemoreflex was induced by systemic hypoxia caused by N2 breathing for 30 seconds "hypoxic- hypoxia methods" and baroreflex was evoked by intravenous injection (i.v.) of phenylephrine (Phe, 20 µg /kg/0.05–0.1 mL). N2 induced generalized vasodilatation followed by tachycardia reflex and Phe evoked vasoconstriction followed by bradycardia.

Results: Microinjection of Cocl2 (5 mM/100 nL/side) produced no significant changes in the Phe-induced hypertension and bradycardia, whereas the cardiovascular effect of N2 was significantly attenuated by the injection of CoCl2 to the KF.

Conclusion: The KF played no significant role in the baroreflex, but could account for cardiovascular chemoreflex in urethane anesthetized rats.

Keywords: Chemoreflex, Baroreflex, Kölliker-Fuse, Cobalt chloride

Copyright and License Information

© 2020 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

The parabrachial (PBN) and Kölliker-Fuse (KF) are nuclei that are located in the dorsal lateral part of the pons.1 The KF nucleus refers to a population of largely glutamatergic neurons2 that receive axonal termination from the retrotrapezoid nucleus and the caudal portion of the nucleus tractus solitarius, the area in the brain stem which involves in chemoreflex and baroreflex suggesting a possible role in the chemoreflex and baroreflex control.3-5 The C-Fos-immunoreactive study showed the intense activation of labeled KF neurons after hypoxia and hypercapnia.6-9 The KF also has extensive interconnections with brain areas involved in cardiovascular response.10 Electrical or chemical stimulations of loci within the lateral parabrachial nuclei and KF increased arterial pressure and produced mild tachycardia.11 The KF region contributes to respiratory chemoreflex but there was no study investigating the cardiovascular chemoreflex by hypoxic-hypoxia methods.

This study aimed to investigate the role of the KF on a chemoreflex and baroreflex. Chemoreceptors were activated by systemic hypoxia produced by a short period of 8% O2 and 92% N2 inhalation, hypoxic- hypoxia methods.12 The present study specifically tested the effect of microinjection of reversible synaptic blocking Cocl2 into the KF on cardiovascular baroreflex and chemoreflex. Cobalt chloride reversibly blocks the calcium channel conductance and therefore synaptic transmission synaptic blockade.

Materials and Methods

Anesthesia and surgery

All experiments were performed using 28 adult male Sprague Dawley rats (250–300 g, 10–11 weeks old) housed in the university animal care following the guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. All efforts were made to minimize discomfort and the number of animals used.

The rats had free access to food and water under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with a room temperature of ~ 25°C. Surgical procedures were similar to our previous experiments. General anesthesia was induced with urethane, with an initial dose of 1.4 g/kg; i.p. Surgical anesthesia was affirmed if no withdrawal reflex of a hind limb was observed. The adequacy of anesthesia was examined regularly and a supplementary dose (10% of the initial dose i.p) was administered as needed.

Rectal temperature was monitored and maintained at 37±1 by the heating pad temperature controller.

The trachea was cannulated to facilitate ventilation. In some groups, the animals were mechanically ventilated using a small rodent ventilator (Harvard Apparatus; model 683). A polyethylene catheter (PE-50, AD instrument) filled with heparinized saline was inserted into the femoral artery and vein for recording the arterial pressure and activating chemoreflex, respectively. To record arterial pressure and heart rate, the femoral artery cannula was connected to an ML T844 pressure transducer coupled to a pre-amplifier (FE221 Bridge amplifier, AD instruments, AU) connected to a power lab 4/35 data acquisition system (model PL3504 AD instruments, AU). For drug microinjection into the KF, rats were placed on a stereotaxic frame (Stoleting, USA). The skull was drilled above the KF at coordinates of 2.45-2.55 mm lateral from midline, 8.6–9.2 mm caudal to bregma and 7.4–8.2 mm below to the surface of bregma according to a rat brain atlas.13

Drug microinjections and baroreflex and chemoreflex activation

Glass micropipettes (Stoleting, USA) were pulled by a micropipette puller (Narishigi, Japan). A single barrel micropipette was inserted into each KF for bilateral microinjection. Saline and cobalt chloride (100 nL/side) were microinjected into the KF using a micropipette with a tip diameter of 35-45 µm. The volume of Injection was monitored by direct observation of fluid meniscus in the micropipettes that allowed a 2-nL resolution (U.W.O, Canada). Cobalt chloride was dissolved in saline. Carotid chemoreceptor stimulation was done by ventilating the rats with 8% O2 in 92% N2 for 1-2 minutes using ventilator "hypoxic- hypoxia methods".14 Baroreceptor activation was done with i.v. administration of phenylephrine (Phe, 20 µg /kg/0.05–0.1 mL).

Data analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). All data were tested for normality (Shapiro-Wilk test). Since all data were normal, parametric tests were used. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were compared with the pre-injection values using paired t-test, and different interval values were compared using repeated-measures ANOVA. A P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. To evaluate the cardiovascular chemoreflex, the mean of the peak tachycardia and hypotension after 8% O2 breathing were calculated and compared with those of the pre-intervention (injecting of cocl2). The baroreflex activity was evaluated by measurement of the increase of MAP, maximum of decrease in heart rate, and the baroreflex gain (the ratio of the maximum ΔHR to the maximum ΔMAP). The values were compared before, and 5, 15, and 40 minutes after treatments using repeated-measures ANOVA. Moreover, the values were compared with the preinjection values using a paired t-test.

Experimental groups

The first group: Activation of arterial baroreceptors was performed by intravenous injections of Phe before (control) and 5, 15, and 40 minutes after bilateral microinjection saline (100 nL/each side, n=8 rats) into the KF.

The second group: Activation of arterial baroreceptors was performed before (control) and 5, 15, and 40 minutes after bilateral microinjection cobalt chloride (CoCl2, 5 mM, 100 nL/side, Sigma, USA, n = 7 rats) into the KF.15

The third group: Arterial chemoreceptors were activated with the inhalation of 8% O2 and 92% N2 before (control) and 5, 15, and 40 minutes after bilateral microinjection saline (100 nL/each side, n = 6 rats) into the KF.

The fourth group: Activation of arterial chemoreceptors was evoked before (control) and 5, 15, and 40 minutes after bilateral microinjection cobalt chloride (CoCl2, 5 mM, 100 nL/side, n = 7 rats) into the KF.

Histology

At the end of the experiments, rats were anesthetized with a high dose of urethane. The chest was surgically opened, the descending aorta occluded, the right atrium cut off and the brain perfused with saline followed by 100 mL of formalin (10%) through the left ventricle. Brains were postfixed for at least 24 and 50 μm sections of the brain at the level of the pons were cut using a cryostat (Microm HM 525, Germany). Sections were mounted on glass slides and stained with cresyl violet (1%). All stimulation sites were mapped according to a rat brain atlas,13 under the light microscope.

Results

Effects of saline on the cardiovascular baroreflex and gain

For the control group, baroreflex responses were evoked by intravenous injection of Phe used to activate arterial baroreceptors before and 5, 15, and 40 minutes after bilateral injection of saline (100 nL/side) into the KF of spontaneously breathing rats (n = 8 rats).

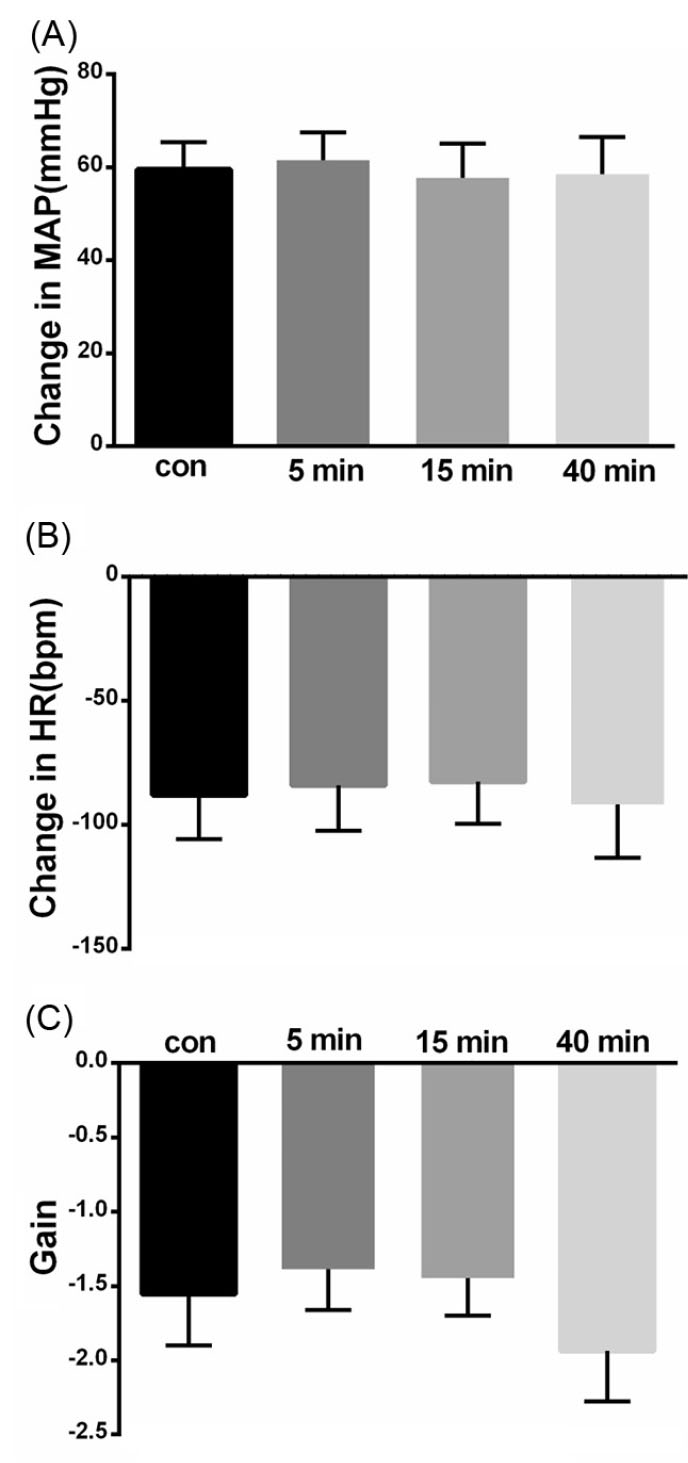

Microinjection of saline did not significantly affect the baseline values MAP, HR (MAP= 100.6±5.8 vs. 100.4±5.8 mm Hg and HR=317.4±6.7 vs. 325.5 ±9.2 bpm, n = 8 rats; paired t-test, P > 0.05, Fig. 1). Microinjection of saline also had not a significant effect on the pressor or bradycardic responses of the cardiovascular baroreflex and gain (pressor before = 59.54±5.87 mm Hg, after 5 minutes: 61.54±5.95 mmHg; bradycardia: before = -88±17.78 bpm, after 5 minutes: -84.18 ± 18.19 bpm; gain: before = -1.55±0.34 after -1.38±0.27; paired t-test between before and 5 minutes after: P > 0.05, repeated measures ANOVA: P > 0.05; Fig. 1) confirming that the changes seen in the other groups are not due to the injection of the vehicle.

Fig. 1.

Bar chart summarizing baroreflex responses before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after saline microinjection into the KF. (A) mean pressor response, (B) mean bradycardic response, (C) gain.

.

Bar chart summarizing baroreflex responses before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after saline microinjection into the KF. (A) mean pressor response, (B) mean bradycardic response, (C) gain.

Cardiovascular baroreflex and gain to microinjection of cobalt chloride into the KF

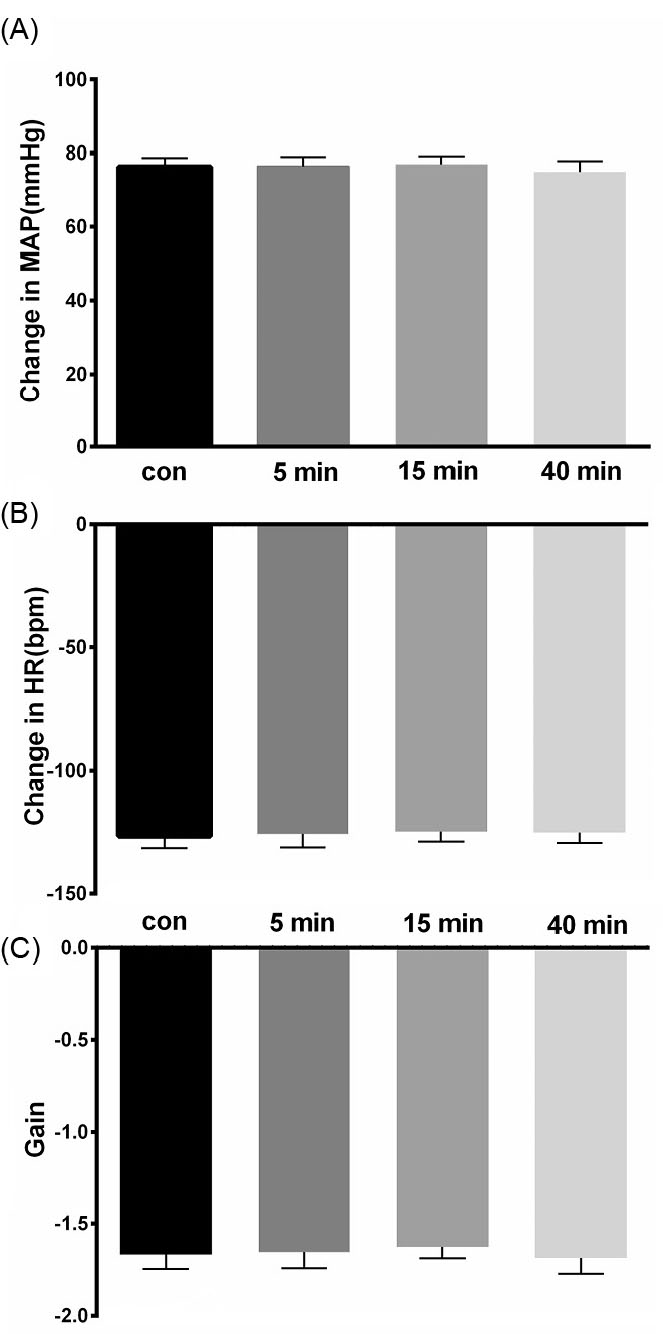

To find if the KF neurons play a role in the cardiovascular baroreflex, the KF was reversibly blocked bybilateral cobalt chloride (CoCl2, 5mM, 100 nL/side,). Microinjection of CoCl2 into the KF did not significantly affect the baseline values of MAP and HR (MAP= 82.71 ± 4.45 vs. 83.25 ± 4.43 mm Hg and HR = 351.71 ± 14.71 vs. 351.28 ± 14.30 bpm, paired t-test, P> 0.05, n = 7 rats). Systemic administration of Phe before and after bilateral injection of CoCl2had no significant effect on the pressor, bradycardic and gain responses of the cardiovascular baroreflex (pressor before = 76.28±2.38 mm Hg, after 5 minutes: 76.42 ± 2.47 mm Hg; bradycardia: before = -126.85±4.93 bpm, after 5 minutes: -126 ± 5.52 bpm; gain: before = -1.67±0.07 after -1.65 ± 0.08; repeated measures ANOVA: P > 0.05; paired t-test between before and 5 minutes after: P > 0.05, Figs. 2 and 3).

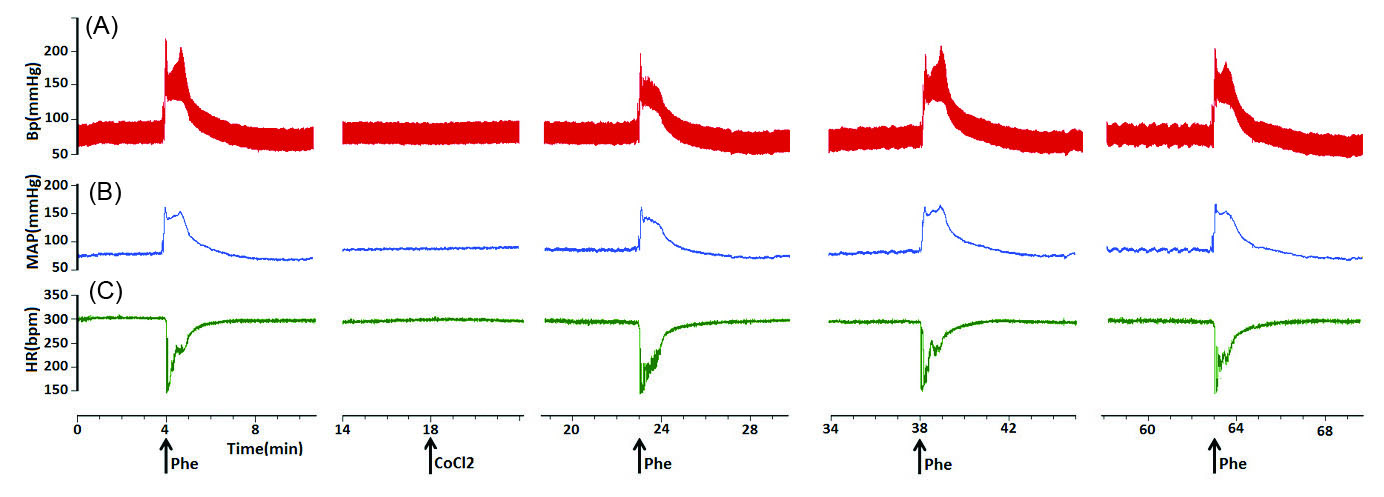

Fig. 2.

Representative tracings showing the baroreflex before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after bilateral microinjection of CoCl2 (5 mM, 100 nL/ side) into the KF. Note the pressor and bradhycardic responses to i.v. injection of phenylepherine (20 µg/kg/ 0.05–0.1 mL). The arrows show the injection times. (A)arterial pressure, (B) MAP, (C) HR.

.

Representative tracings showing the baroreflex before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after bilateral microinjection of CoCl2 (5 mM, 100 nL/ side) into the KF. Note the pressor and bradhycardic responses to i.v. injection of phenylepherine (20 µg/kg/ 0.05–0.1 mL). The arrows show the injection times. (A)arterial pressure, (B) MAP, (C) HR.

Fig. 3.

Bar chart summarizing baroreflex responses before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after CoCl2 (5 mM, 100 nL/ side) microinjection into the KF. (A) mean pressor response, (B) mean bradycardic response, (C) gain.

.

Bar chart summarizing baroreflex responses before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after CoCl2 (5 mM, 100 nL/ side) microinjection into the KF. (A) mean pressor response, (B) mean bradycardic response, (C) gain.

Effects of saline on the cardiovascular chemoreflex

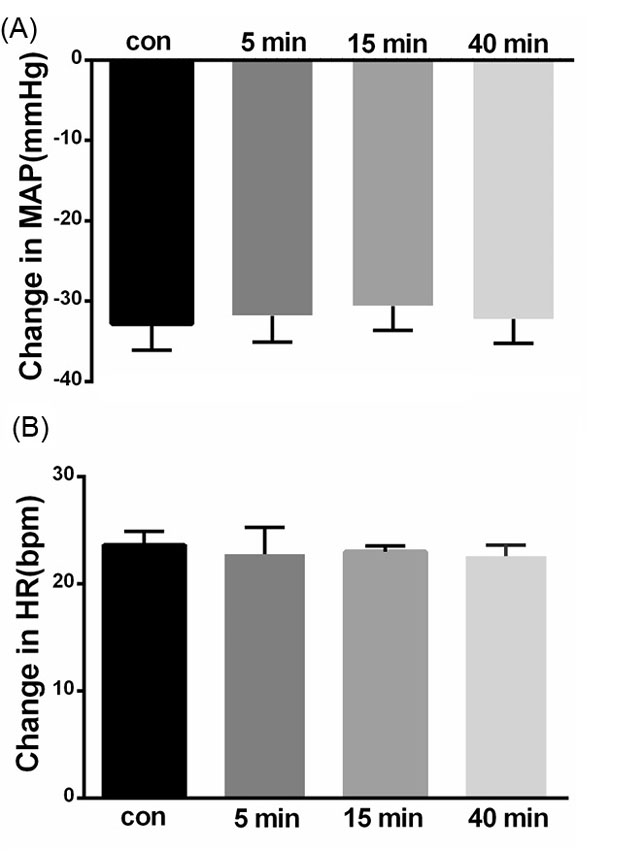

Hypoxia was induced by artificial respiration via a ventilator with 8% O2 in 92% N2 for 1-2 minutes to stimulate arterial chemoreceptors before and 5, 15, and 40 minutes after bilateral injection of saline (100 nL/side) into the KF (n = 6 rats). Hypoxia elicited a fall in arterial pressure with peripheral vasodilatation and tachycardia. Microinjection of saline did not significantly affect baseline values of MAP, HR (MAP = 93.8±5.88 vs. 93.4±5.52 mm Hg and HR=366±13.41 vs 367.2 ±13.44 bpm, n = 6 rats; paired t-test, P > 0.05, Fig. 4). Microinjection of saline also had no significant effect on the depressor or tachycardic responses (depressor before = -32.8±3.30 mm Hg, after 5 minutes: -31.8±3.29 mm Hg; tachycardia: before = 23.6±1.28 bpm, after 5 minutes: -22.8 ±2.47 bpm; repeated measures ANOVA: P > 0.05; paired t-test between before and 5 minutes after: P > 0.05, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Bar chart summarizing chemoreflex responses before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after saline microinjection into the KF. (A) mean depressor response, (B) mean tachycardic response.

.

Bar chart summarizing chemoreflex responses before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after saline microinjection into the KF. (A) mean depressor response, (B) mean tachycardic response.

Effect of microinjection of cobalt chloride into the KF on the cardiovascular chemoreflex

Microinjection of CoCl2 (5mM, 100 nL/side, n = 7 rats) into the KF did not significantly affect the baseline values of MAP and HR (MAP = 103.28±5.41 vs. 103.28±5.37 mm Hg and HR = 391.71±11.26 vs. 391.85 ± 11.21 bpm, paired t-test,P > 0.05, n = 7 rats, Fig. 5).

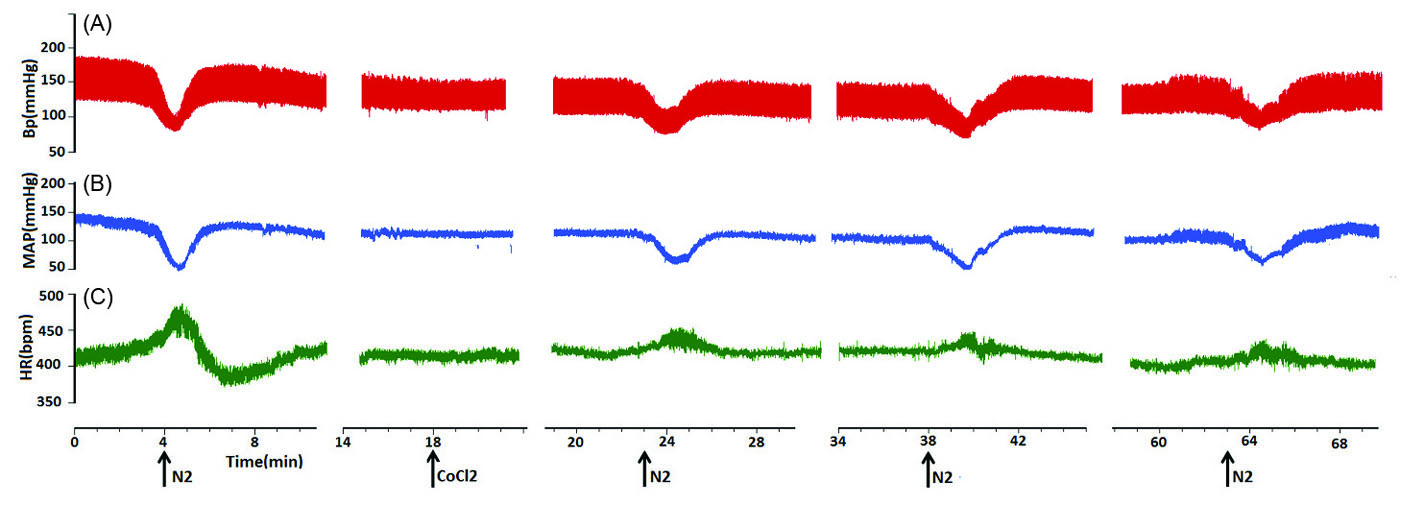

Fig. 5.

Representative tracings showing the chemoreflex before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after bilateral microinjection of CoCl2 (5 mM, 100 nL/ side) into the KF. Note the tachycardic responses attenuated after 8% O2 respiration. The arrows show the injection times. (A) arterial pressure, (B) MAP, (C) HR.

.

Representative tracings showing the chemoreflex before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after bilateral microinjection of CoCl2 (5 mM, 100 nL/ side) into the KF. Note the tachycardic responses attenuated after 8% O2 respiration. The arrows show the injection times. (A) arterial pressure, (B) MAP, (C) HR.

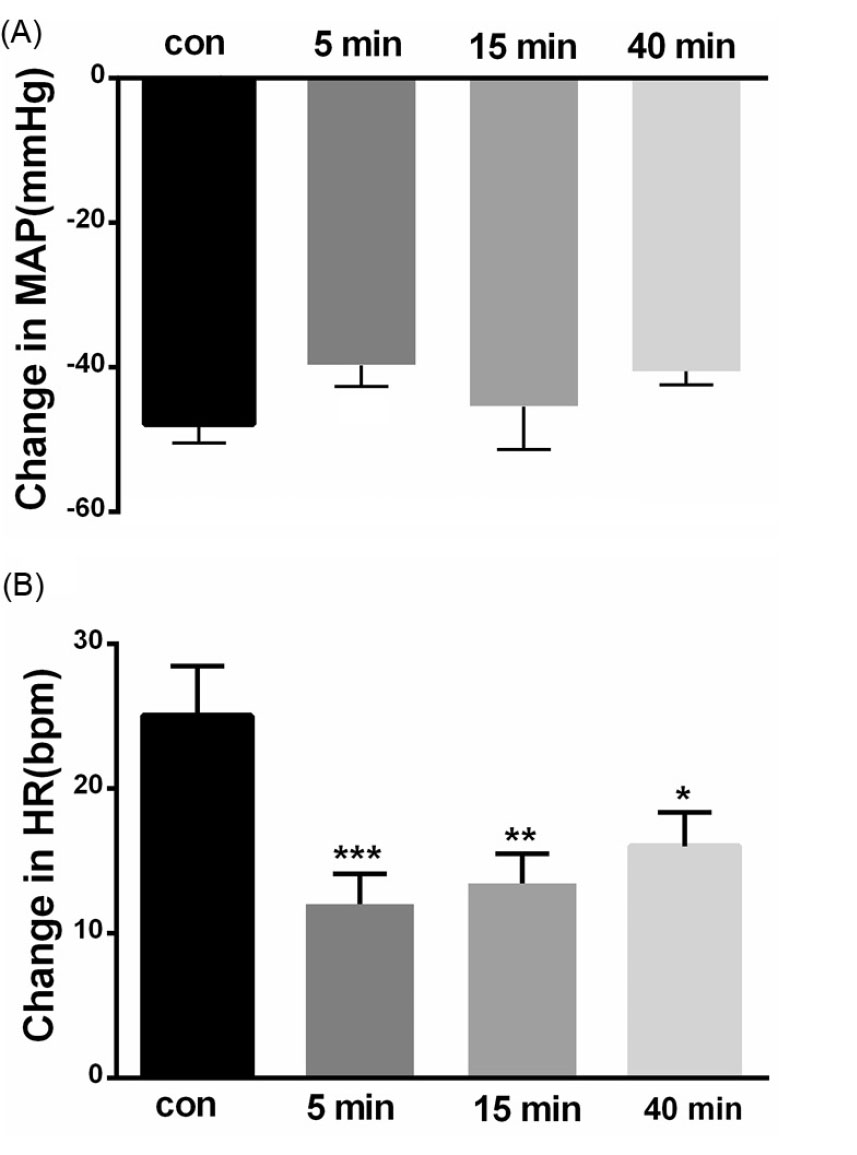

Depressor response of chemoreflex did not change by CoCl2 microinjection (depressor before = -47.85±2.59 mm Hg, after 5 and 15 minutes: -39.7±2.92 and -45.41±5.92 mm Hg respectively P > 0.05 paired t-test; tachycardia: before = 25±3.45 bpm, after 5 and 15 minutes: 12 ±2.09 and 13.4 ±2.0 bpm respectively P < 0.001, after 40 minutes: 16.0 ±2.3 bpm, P < 0.01, Fig. 6.) repeated measures ANOVA: P < 0.01; indicating that the KF neuronal network plays a role in producing tachycardia of cardiovascular chemoreflex.

Fig. 6.

Bar chart summarizing chemoreflex responses, before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after CoCl2 microinjection into the KF (paired t test, **P< 0. 01, ***P< 0.001). (A) mean depressor response, (B) mean tachycardic response.

.

Bar chart summarizing chemoreflex responses, before, and 5, 15 and 40 minutes after CoCl2 microinjection into the KF (paired t test, **P< 0. 01, ***P< 0.001). (A) mean depressor response, (B) mean tachycardic response.

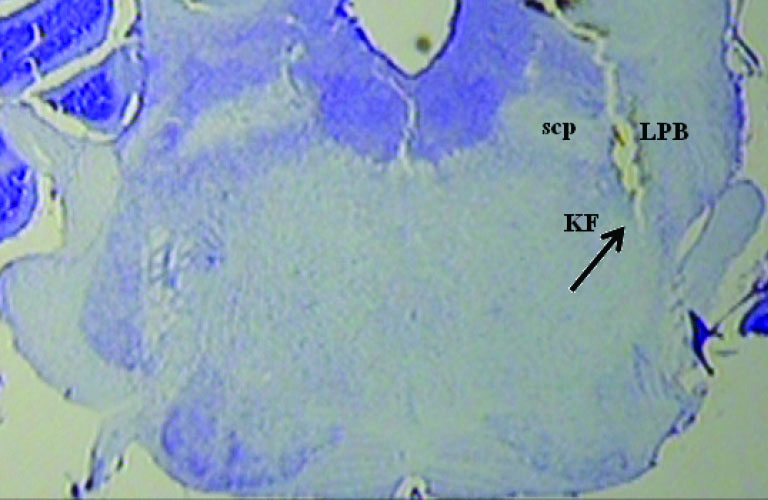

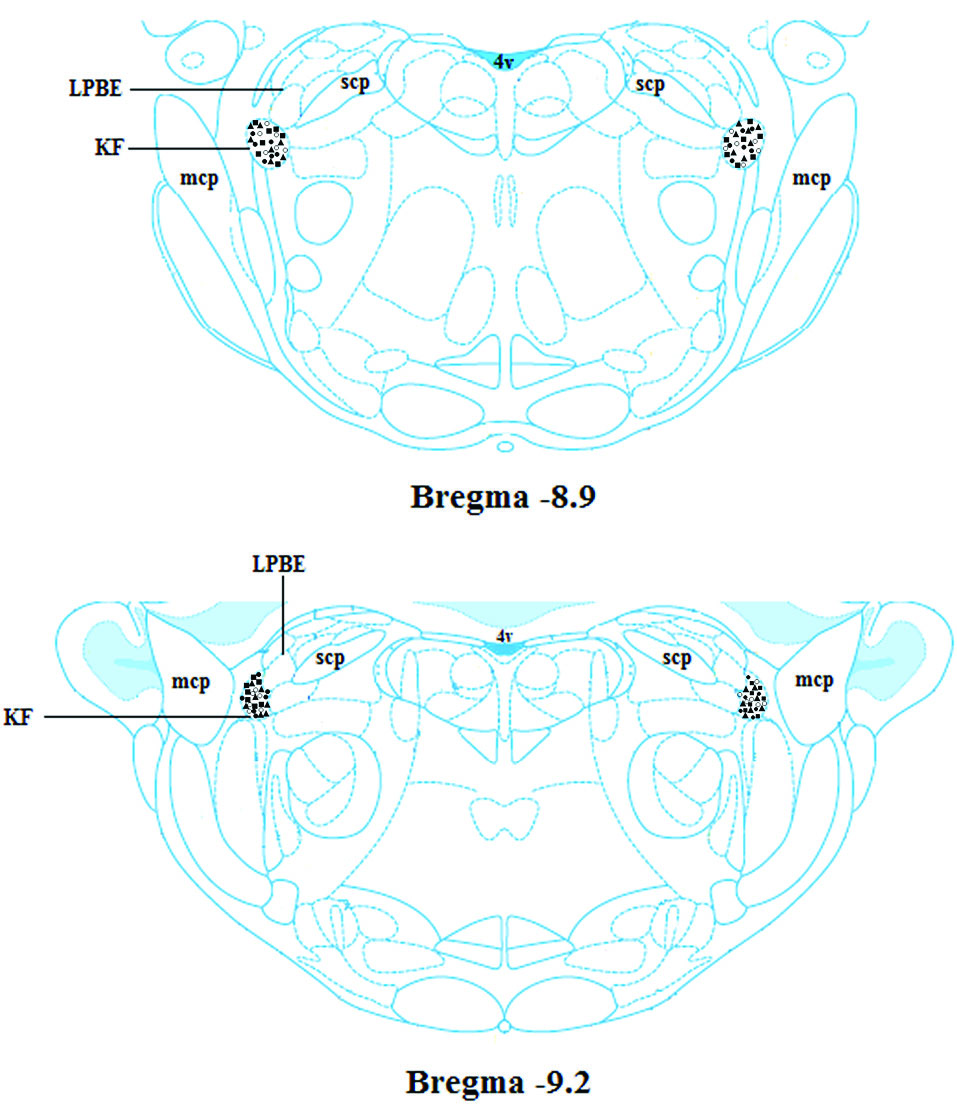

Histology

A photomicrograph with two injection sites is displayed in Fig. 7. The diagrammatic representation base on rat brain atlas is shown in Fig. 8. Data of the injection sites outside the KF were not included in the analysis.

Fig. 7.

A photomicrograph with injection site. scp: superior cerebellar peduncle, LPB: lateral parabrachial nucleus.

.

A photomicrograph with injection site. scp: superior cerebellar peduncle, LPB: lateral parabrachial nucleus.

Fig. 8.

Schematic coronal section of rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007), showing the injection sites in the KF. 4 V: the 4th ventricle, KF: the Kȍlliker-Fuse nucleus, LPB: the lateral parabrachial nucleus, mcp: the middle cerebellar peduncle, MPB: the medial parabrachial nucleus, scp: the superior cerebellar peduncle.

.

Schematic coronal section of rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007), showing the injection sites in the KF. 4 V: the 4th ventricle, KF: the Kȍlliker-Fuse nucleus, LPB: the lateral parabrachial nucleus, mcp: the middle cerebellar peduncle, MPB: the medial parabrachial nucleus, scp: the superior cerebellar peduncle.

Discussion

The peripheral chemoreflex responses are an important mechanism during the hypoxic state in a patient with sleep apnea, hypertension16,17 and sudden infant death syndrome.18 The present study provides the cardiovascular evidence indicating the involvement of the KF nucleus in the cardiovascular chemoreflex evoked by systemic inhalation of 8% O2 and 92% of N2 in artificially ventilated urethane anesthetized rats. Whereas the KF had no effect on baroreflex evoked by systemic administration of phenylephrine. In this study, hypoxia was used to stimulate arterial chemoreceptors, Hypoxia elicited hypotension due to peripheral vasodilatation and the reflex of tachycardia. This response was similar to that reported by other investigators using N2 to elicit chemoreflex responses in pentobarbitone -anesthetized rats.12 Lack of response to saline microinjection demonstrated that the baroreceptors and chemoreceptors cardiovascular responses were not owing to mechanical distortion or volume injection (Figs. 1 and 4).

To find the possible involvement of the KF in the cardiovascular chemoreflex, cobalt chloride, a reversible synaptic blocker was used. Bilateral microinjections of CoCl2 into the KF markedly attenuated the component of tachycardic response with no change in depressor response which is due to peripheral vasodilatation (Figs. 5 and 6), confirming that the KF is an important site for generating cardiovascular chemoreflex. Anatomical and physiological pieces of evidence have already demonstrated that the KF receives peripheral chemoreceptor signals.6-9 The recovery time of CoCl2 was ranged from 20-40 minutes (Figs. 2 and 5) and complete recovery from the effects occurred within 60 minutes. The effect of hypoxia to generate chemoreflex responses was extremely reproducible and highly significant as indicated in the figures.

Baroreceptor activations were performed by systemic administration of Phe before and after reversible synaptic blocker, which had no significant effect on the pressor and bradycardic reflex and gain (Fig. 3) confirming that the KF does not receive arterial pressure information from baroreceptors and has no role in baroreflex.

A possible criticism of this study is the use of hypoxia (8% O2), and the generation of peripheral hypotension may activate the baroreflex due to the direct effects of decreased arterial pressure on the baroreceptors. In contrast, during baroreflex activation, sympathoexcitation occurs, which stimulates primarily central chemoreceptors. The baroreceptor-chemoreceptor interaction was previously described in animals,19-22 and humans.23 In the clinic, the baroreflex impairment known to occur in hypertension may result in a loss of the inhibitory tonic or inhibitory permeation of baroreceptors on the excitatory effect of chemoreceptors during hypoxia. Activation of the baroreflexes has an inhibitory influence on chemoreflex gain as we see in sleep apnea.24 Activation of the baroreflex can inhibit both ventilatory and autonomic responses to chemoreflex activation.23,25,26 Conditions that are associated with impaired baroreflex gains, such as hypertension and heart failure,23,25 would also be accompanied by exaggerated chemoreflex responses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that the KF has no role in baroreflex but plays an essential role in cardiovascular chemoreflex.

Funding sources

This manuscript was derived from a project, financially supported by the Vice Chancellery of Research, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (grant number: 20216).

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.SUMS.REC.1398.330).

Competing interests

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Authors’ contribution

MH: supervision, design of experiments, writing the manuscript, interpretation of data. NMD: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. BR: helping in the acquisition of data.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

simple

-

√ The Kölliker-Fuse (KF) located in dorso-lateral pons is

involved in the regulation of cardiovascular and respiratory

functions.

-

√ Hypoxia activated afferent fibers of peripheral

chemoreceptors which are relayed to the brain stem and KF

nucleus.

-

√ The KF also has interconnections with brain areas involved

in cardiovascular response.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ Hypoxic-hypoxia methods were used to stimulate arterial

chemoreceptors and generate depressor and tachydardic

responses.

-

√ Blockade of neuronal transmission KF by local injection

of CoCl2 markedly attenuated tachycardia component of

chemoreflex response.

-

√ Phenylepherine was used to stimulate arterial baroreceptor

and generate pressor and bradydardic responses.

-

√ Microinjection of CoCl2 into the KF had no effect on

baroreflex.

References

- Baker TL, Netick A, Dement WC. Sleep-related apneic and apneustic breathing following pneumotaxic lesion and vagotomy. Respir Physiol 1981; 46(3):271-94. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(81)90127-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Saper CB, Loewy AD. Commentary on: Efferent connections of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. C.B. Saper and A.D. Loewy, Brain Res .197:291-317, 1980. Brain Res 2016;1645:15-7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.01.009.

- Herbert H, Moga MM, Saper CB. Connections of the parabrachial nucleus with the nucleus of the solitary tract and the medullary reticular formation in the rat. J Comp Neurol 1990; 293(4):540-80. doi: 10.1002/cne.902930404 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rosin DL, Chang DA, Guyenet PG. Afferent and efferent connections of the rat retrotrapezoid nucleus. J Comp Neurol 2006; 499(1):64-89. doi: 10.1002/cne.21105 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Song G, Wang H, Xu H, Poon C-S. Kölliker–Fuse neurons send collateral projections to multiple hypoxia-activated and nonactivated structures in rat brainstem and spinal cord. Brain Struct Funct 2012; 217(4):835-58. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0384-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Berquin P, Cayetanot F, Gros F, Larnicol N. Postnatal changes in Fos-like immunoreactivity evoked by hypoxia in the rat brainstem and hypothalamus. Brain Res 2000; 877(2):149-59. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02632-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bodineau L, Larnicol N. Brainstem and hypothalamic areas activated by tissue hypoxia: Fos-like immunoreactivity induced by carbon monoxide inhalation in the rat. Neuroscience 2001; 108(4):643-53. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00442-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hirooka Y, Polson JW, Potts PD, Dampney RA. Hypoxia-induced Fos expression in neurons projecting to the pressor region in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Neuroscience 1997; 80(4):1209-24. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00111-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Teppema LJ, Veening JG, Kranenburg A, Dahan A, Berkenbosch A, Olievier C. Expression of c-fos in the rat brainstem after exposure to hypoxia and to normoxic and hyperoxic hypercapnia. J Comp Neurol 1997; 388(2):169-90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971117)388:2<169::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO;2-%23 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shafei MN, Nasimi A. Effect of glutamate stimulation of the cuneiform nucleus on cardiovascular regulation in anesthetized rats: role of the pontine Kolliker-Fuse nucleus. Brain Res 2011; 1385:135-43. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.02.046 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Korte SM, Jaarsma D, Luiten PG, Bohus B. Mesencephalic cuneiform nucleus and its ascending and descending projections serve stress-related cardiovascular responses in the rat. J Auton Nerv Syst 1992; 41(1-2):157-76. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(92)90137-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. Analysis of cardiovascular responses evoked following changes in peripheral chemoreceptor activity in the rat. J Physiol 1987; 394:393-414. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016877 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

-

Paxinos G WC. A stereotaxic Atlas of the Rat Brain. New York: Academic; 2007.

- Koshiya N, Huangfu D, Guyenet PG. Ventrolateral medulla and sympathetic chemoreflex in the rat. Brain Res 1993; 609(1-2):174-84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90871-j [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei-Damabi N, Namvar GR, Yeganeh F, Hatam M. alpha2 Receptors in the lateral parabrachial nucleus generates the pressor response of the cardiovascular chemoreflex, effects of GABAA receptor. Brain Res Bull 2018; 140:190-6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.05.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR, Peng YJ, Kumar GK, Pawar A. Altered carotid body function by intermittent hypoxia in neonates and adults: relevance to recurrent apneas. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2007; 157(1):148-53. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.12.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. HIF-1-dependent respiratory, cardiovascular, and redox responses to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Antioxid Redox Signal 2007; 9(9):1391-6. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1691 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gauda EB, Cristofalo E, Nunez J. Peripheral arterial chemoreceptors and sudden infant death syndrome. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2007; 157(1):162-70. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.02.016 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Heistad D, Abboud FM, Mark AL, Schmid PG. Effect of baroreceptor activity on ventilatory response to chemoreceptor stimulation. J Appl Physiol 1975; 39(3):411-6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.39.3.411 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mancia G. Influence of carotid baroreceptors on vascular responses to carotid chemoreceptor stimulation in the dog. Circ Res 1975; 36(2):270-6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.2.270 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Heistad DD, Abboud FM, Mark AL, Schmid PG. Interaction of baroreceptor and chemoreceptor reflexes Modulation of the chemoreceptor reflex by changes in baroreceptor activity. J Clin Invest 1974; 53(5):1226-36. doi: 10.1172/JCI107669 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mancia G, Shepherd JT, Donald DE. Interplay among carotid sinus, cardiopulmonary, and carotid body reflexes in dogs. Am J Physiol 1976; 230(1):19-24. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.1.19 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Somers VK, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Interaction of baroreceptor and chemoreceptor reflex control of sympathetic nerve activity in normal humans. J Clin Invest 1991; 87(6):1953-7. doi: 10.1172/JCI115221 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mansukhani MP, Wang S, Somers VK. Chemoreflex physiology and implications for sleep apnoea: insights from studies in humans. Exp Physiol 2015; 100(2):130-5. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2014.082826 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Somers VK, Dyken ME, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Parasympathetic hyperresponsiveness and bradyarrhythmias during apnoea in hypertension. Clin Auton Res 1992; 2(3):171-6. doi: 10.1007/bf01818958 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, van de Borne PJ, Montano N, Dyken ME, Phillips BG, Somers VK. Contribution of tonic chemoreflex activation to sympathetic activity and blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 1998; 97(10):943-5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.943 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]