BioImpacts. 9(1):5-13.

doi: 10.15171/bi.2019.02

Original Research

Carboxymethylcellulose/MOF-5/Graphene oxide bio-nanocomposite as antibacterial drug nanocarrier agent

Zahra Karimzadeh 1, Siamak Javanbakht 1, Hassan Namazi 1, 2, *

Author information:

1 Research Laboratory of Dendrimers and Nanopolymers, Faculty of Chemistry, University of Tabriz, P.O. Box 51666, Tabriz, Iran

2 Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology, Biomedicine Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Introduction:

In recent years, more attention was dedicated to developing new methods for designing of drug delivery systems. The aim of present work is to improve the efficiency of the antibacterial drug delivery process, and to realize and to control accurately the release.

Methods:

First, graphene oxide (GO) was prepared according to the modified Hummers method then the GO was modified with carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) and Zn-based metal-organic framework (MOF-5) through the solvothermal technique.

Results:

Performing the various analysis methods including scanning electron microscope (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), EDX, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and Zeta potentials on the obtained bio-nanocomposite showed that the new modified GO has been prepared. With using common analysis methods the structure of synthesized materials was determined and confirmed and finally, their antibacterial behavior was examined based on the broth microdilution methods.

Conclusion:

Carboxymethylcellulose/MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite (CMC/MOF-5/GO) was successfully synthesized through the solvothermal technique. Tetracycline (TC) was encapsulated in the GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO. The drug release tests showed that the TC-loaded CMC/MOF5/GO has an effective protection against stomach pH. With controlling the TC release in the gastrointestinal tract conditions, the long-time stability of drug dosing was enhanced. Furthermore, antibacterial activity tests showed that the TC-loaded CMC/MOF-5/GO has an antibacterial activity to negatively charge E. coli bacteria in contrast to TC-loaded GO.

Keywords: Antibacterial, Bio-nanocomposite, Carboxymethylcellulose, Graphene oxide, Metal-organic framework, Nanocarrier

Copyright and License Information

© 2019 The Author(s)

This work is published by BioImpacts as an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

In recent years, various de novo methods have been developed for designing drug delivery systems (DDSs).

1,2

An ideal DDS should convey a suitable concentration of drug to targeting sites and enhance the drug efficacy.

3,4

Thus, one of the main challenges to reach this aim is finding a suitable delivery carrier.

5,6

Currently, among various carriers including polymeric particles,

7,8

nanomaterials,

6

microspheres,

9

dendrimers

10

and liposomes

11

which were used as potential drug carriers, nanomaterial demonstrate advantages for drug delivery.

12

The efficiency of conventional drugs and facilitate many of the free drug therapeutic pitfalls can be enhanced by nanoparticle-based therapeutics. Nanocarriers can improve considerably the effect and delivery of drugs, especially when drugs are poorly water-soluble. Nanoparticle–drug conjugates under different stages were developed in clinical therapies and illustrates the clinical success of nanoparticle therapies.

4,13

Recently, several reports have announced the synthesis of metal-organic framework (MOF) and graphene oxide (GO) nanocomposites.

14-16

MOF is self-assembled from various organic linkers and metal ions as nodes.

15,17,18

GO is a compound of carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen in variable ratios that could be obtained by treating graphite with strong oxidizers.

19-21

The hydroxyl and epoxy functional groups of GO permit the act of metal ions in MOFs to be formed as composite hence, the idea of MOF-GO nanocomposites is developed. So, by merging the complementary features of 2 materials, GO becomes dense arrays of layers and nonporous. The critical drawback of MOF is void space and is not beneficial for the retention of small molecules such as drug molecule under ambient conditions.

22

Moreover, the critical drawbacks of MOFs and GO may resolve by the composition of GO and MOFs.

23

Recently, some new results about MOF–GO hybrids

24

have reported using various MOFs, for example, Zn-based MOF (MOF-5),

22

Cu-based MOF (HKUST-1 or Cu3(BTC)2, BTC = 1,3,5-benzene tricarboxylate),

25

Zr-based MOF (UiO-66)

26

and Fe-based MOF (MIL-100).

27

However, as far as we know, there are still few studies on the potential of the MOF-GO composites in the drug delivery systems, so evaluation of this system has a good novelty for controlling the drug release.

Typically, many of nanoparticles, for instance, MOF-GO composites suffer from low solubility in the physiological conditions; therefore, these materials need to be modified for the improvement of solubility. Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) is an anionic water-soluble biopolymer that is one of the cellulose derivatives.

28-30

CMC have unique characteristics such as pH-sensitivity, hydrophilicity, non-toxicity, biodegradability, and biocompatibility.

31-33

In biomedical applications because of these CMC features, considerable interests have been focused on CMC prepared carriers.

8,34,35

Therefore, for modification of the nanoparticle, CMC can be a good candidate.

36

Tetracycline (TC) is an industrially available antibiotic used to treat a number of infections. This includes acne, cholera, brucellosis, plague, malaria, and syphilis.

37

One of the major side effects which were observed after oral administration of TC is irritation of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). To decrease the high GIT side effects, which caused by the oral use of TC , the drug can be encapsulated into biocompatible support as enteric coated dosage forms. As well as, nanomaterial supports with the high surface area such as GO could enhance the medicinal efficiency, and also the medical performance can be improved even more through modification of nanoparticle.

In our ongoing research program, related to developing the new drug delivery system

38,39

based on our previous investigations on GO,

40,41

the CMC-modified MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite was prepared as a novel drug delivery system. Antibacterial drug TC was highly loaded to the CMC/MOF-5/GO, then the release behavior was investigated. Drug loading and release manner of prepared CMC/MOF-5/GO by combining the complementary features of the three materials (CMC, MOF-5 and GO) was well optimized. The obtained results showed that this desired carrier system could be potentially used in the antibacterial oral delivery systems.

Experimental

Material

CMC with the degree of substitution (DS) 0.55–1.0 and viscosity 15000 MP/s (1% in H2O, 25°C) were obtained from Nippon Paper Chemicals Co., Ltd., Japan. TC was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Zinc nitrate hexahydrate, 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate (BDC), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), CHCl3 and all other materials were purchased from Merck.

Characterization and analysis

UV–Vis absorption spectra were obtained on a Shimadzu 1700 Model UV–Vis spectrophotometer. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on an FT-IR spectrometer (Bruker Instruments, model Aquinox 55, Germany) in the 4000–400 cm−1 range at a resolution of 0.5 cm−1 as KBr pellets. X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed at room temperature by Siemens diffractometer with using Cu-Kα radiation at 35 kV in the scan range of 2θ from 5 to 25°. The surface morphology and EDX of the samples were investigated using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (LEO 1430VP) after coating the samples with gold films. The dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential measurements were obtained with a DLS-ZP/Particle Sizer (Microtrac, model Nanotrac Wave).

Synthesis of CMC/MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite

According to the modified Hummers method, GO was prepared from graphite powder.

42

A flask emblematic 46 mL of H2SO4 (98%) was immersed into an ice bath. Then 2.0 g graphite was added to the flask and stirred vigorously. Next, 6.0 g KMnO4 was slowly added into the flask and for about 30 minutes the reaction temperature was kept below 20°C in an ice bath. The flask containing the reaction mixture was then heated with a water bath at a temperature of 35°C, and until a thick paste was formed the reaction mixture was stirred for about 45 minutes. 46 mL water was added to the flask and the reaction temperature was increased to 90°C then the reaction mixture was stirred for about 30 minutes. Finally, 280 mL water was added to the mixture, followed by a slow addition of 10 mL of 30% aq. H2O2. A yellow dispersion was obtained and until about pH 7 the mixture was washed severally with deionized water to remove the remained salt, then the product was dried under vacuum (50°C) for about 24 hours.

The GO (0.33 g) was dispersed in DMF solution by sonication to get DMF emulsion of GO. The CMC/MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite was prepared via the solvothermal route with some modifications on MOF-5.

14,43

In a typical reaction, zinc nitrate hexahydrate (5.2 g), BDC (1.0 g), and CMC (0.33 g) were mixed in 35 mL of GO/DMF solution. The mixture was treated solvothermal at 120°C for 25 hours. Finally, the resulted solid sample was washed with DMF and CHCl3, and CMC/MOF-5/GO was obtained by vacuum drying at 80°C using desiccator equipped with a heater. In order to the synthesis of pure MOF-5, the same procedure was applied without the employment of CMC and GO.

Drug loading and release studies

In purpose of drug loading in the GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO, equal mass (200 mg) from each sample was immersed in 20 mL aqueous solution of 100 ppm drug concentration. After a continuous shaking for 72 hours in the dark, the TC loading capacity was determined using UV–Vis spectrophotometer at 276 nm. The TC-loaded GO (TC@GO) and TC-loaded CMC/MOF-5/GO (TC@CMC/MOF-5/GO) were collected by centrifuging and washed thoroughly to remove unloaded drug then dried at 40°C in the oven.

To study the release of TC, in a typical experiment, 10 mg of TC@GO and TC@CMC/MOF-5/GO were immersed in 10 mL buffered solution. For this propose, during a specific period of time, the carrier was suspended in the mediums with pH 1.2, pH 6.8 and pH 7.4 which respectively mimicked the pH of the simulated gastric fluid, the first zone of intestinal fluid and the second zone of intestinal fluid. Firstly, they were immersed to pH 1.2 (for 2 hours), then to pH 6.8 (for 2 hours), and subsequently to pH 7.4 (for 4 hours). At the certain time intervals, adequate amounts of samples were taken up and in order to maintain the volume of buffer constant, the same amount of fresh buffered was replaced.

The loading capacity and cumulative release data were obtained by using a predetermined calibration curve for TC drug. The amount of loaded and released drug respectively was calculated with the following 2 formulas (Eq. 1 and Eq. 2):

Eq. (1)

Eq. (2)

According to the previous report using various kinetics models (Table 1) the release kinetics analysis data were analyzed.

44,45

The kinetics models used to fit the release data

Table 1.

Antibacterial Studies

Against Escherichia coli bacteria (gram negative) and Staphylococcus aureus bacteria (gram positive), the antibacterial properties of the prepared materials were tested. From an overnight culture, grown aerobically in Mueller–Hinton (MH) broth at 37°C, the inoculum of E. coli and S. aureus were prepared. By measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD600) the bacterial concentration was determined. Based on the broth microdilution methods the bacterial minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for blank and TC-loaded GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO were determined.

46

The lowest concentration of an antibacterial material that will inhibit the visible growth of a microorganism after overnight incubation is defined MIC.

47

To determine MIC, from overnight cultures, the bacterial suspensions were prepared and adjusted to 106 CFU/mL. Then a 100 µL of fresh MH broth, 40 µL of bacterial suspension and 60 µL of various concentrations of TC (1, 2, 25, 50, 100, 150, 200 µg/mL), blank and TC-loaded GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO (50, 100, 150, 250, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000 µg/mL) were added to 96-well plate. To assess the viability of the tested organisms, a positive growth control of basal medium was contained. Under linear shaking, the microplates were incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24 hours. Finally, by detecting the well’s conformation the lowest concentration inhibiting the bacterial growth (the MIC value) was measured.

Results

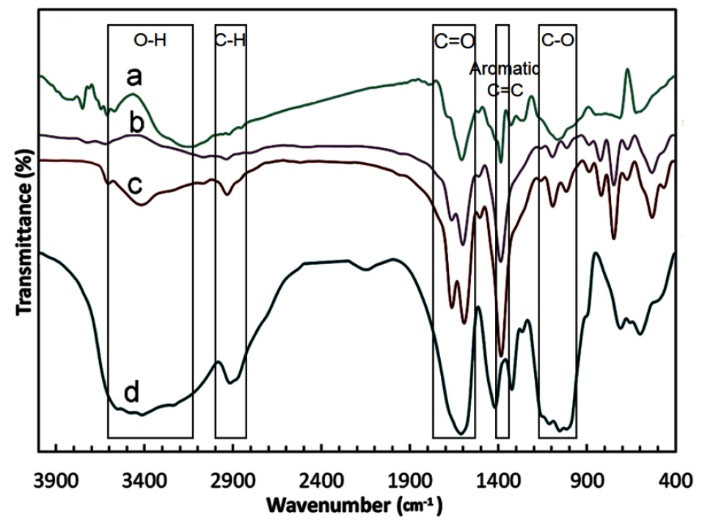

FT-IR analysis

Fig. 1 demonstrates FT-IR spectra to characterize CMC, MOF-5, GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO. The symmetric stretching and asymmetric stretching of the carboxylate groups in MOF-5 and CMC were respectively observed at 1508, 1725 cm-1 and 1539, 1401 cm-1. For MOF-5 and GO could be detected the benzene basic vibration at 1630 cm-1. The several bands that can be observed in the region of 1250–600 cm-1 are related to the out-of-plane vibrations of BDC carboxylate groups for MOF-5. All detected characteristic peaks in CMC/MOF-5/GO with growing intensity in comparison with MOF-5 indicate that the structure of MOF-5, CMC and GO were preserved. For interactions between the –COOH of GO, CMC, and BDC with Zn2+ of CMC/MOF-5/GO the FT-IR results could be good evidences.

Fig. 1.

The FT-IR spectra for the GO (a), MOF-5 (b), CMC/MOF-5/GO (c) and pure CMC (d)

.

The FT-IR spectra for the GO (a), MOF-5 (b), CMC/MOF-5/GO (c) and pure CMC (d)

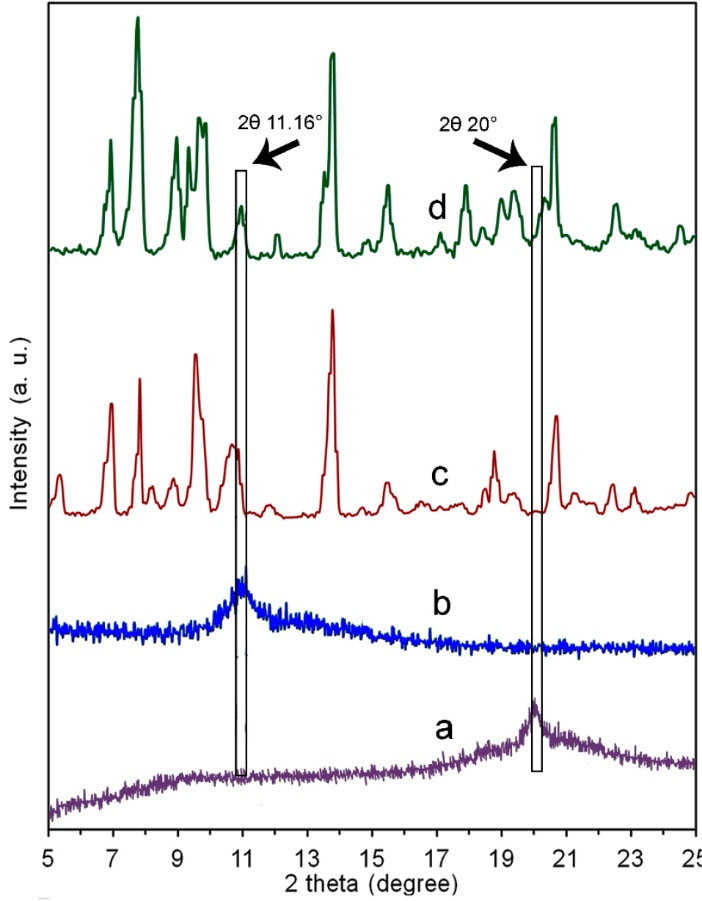

XRD analysis

XRD patterns of the GO, MOF-5, and CMC/MOF-5/GO were shown in Fig. 2. The significant increase of layer spacing with a high degree of orientation of GO was evidenced by border peak at 2θ 11.16° which obvious in the GO XRD spectrum.

48

The XRD pattern of MOF-5 is in good consistency to previous reports (Fig. 2).

43

The broad reflection at 2θ value of about 20° in the CMC/MOF-5/GO XRD pattern is related to the amorphous nature of CMC. Furthermore, the XRD pattern of CMC/MOF-5/GO is similar to the MOF-5, which demonstrates that the MOF-5 structure is preserved. The XRD results proved that the crystalline structure of the MOF-5 component did not distort by the composition of MOF-5, GO and CMC in the CMC/MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite.

43

Fig. 2.

The X-ray diffraction patterns of pure CMC (a), GO (b), MOF-5 (c) and CMC/MOF-5/GO (d). FT-IR spectra for the GO (a), MOF-5 (b), CMC/MOF-5/GO (c) and pure CMC (d)

.

The X-ray diffraction patterns of pure CMC (a), GO (b), MOF-5 (c) and CMC/MOF-5/GO (d). FT-IR spectra for the GO (a), MOF-5 (b), CMC/MOF-5/GO (c) and pure CMC (d)

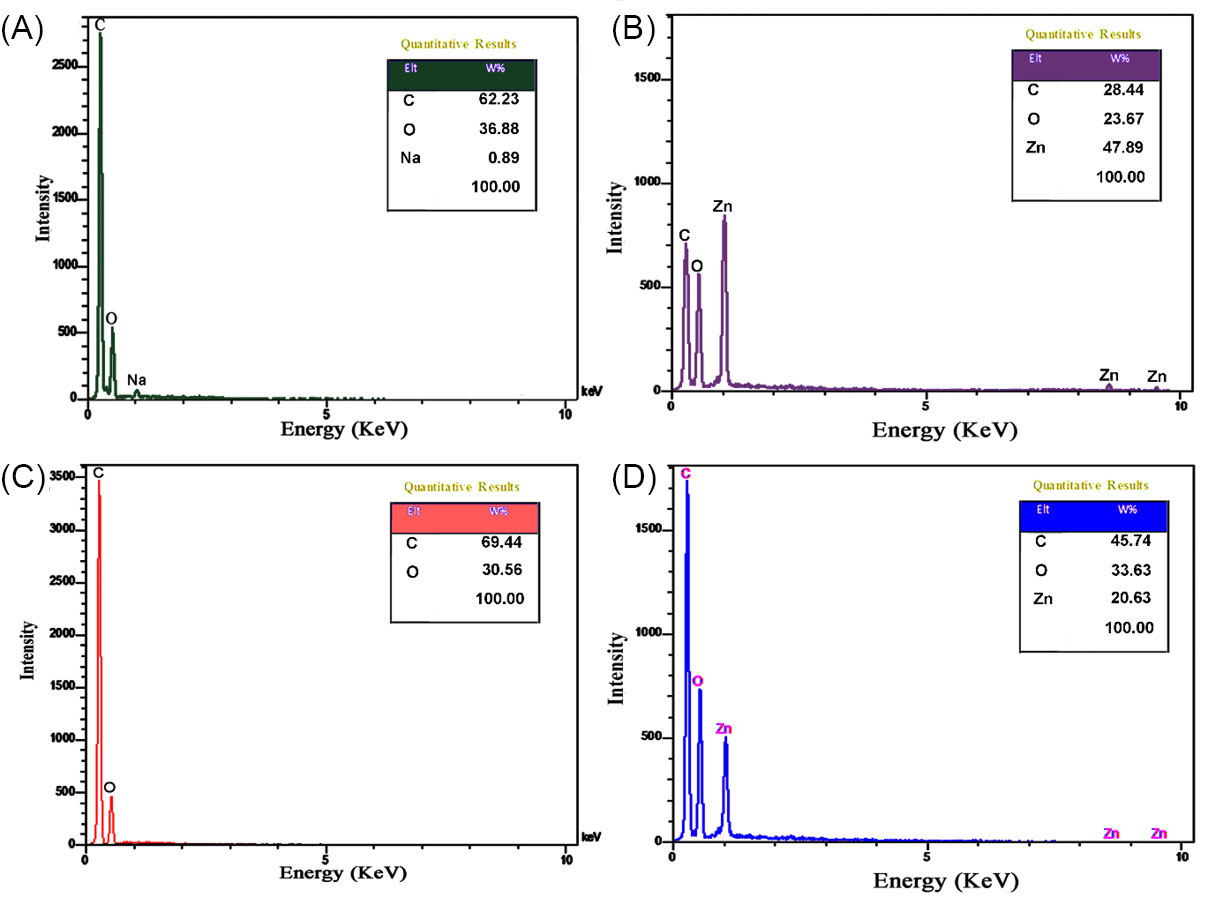

EDX analysis

Element information of samples was obtained using EDX analysis (Fig. 3). The spectrum of CMC (Fig. 3A) shows signals for the presence of C, O and Na with weight percentages 62.23, 36.68 and 0.89 W%, respectively. The EDX signals for MOF-5 (Fig. 3B) displays the presence of C, O, and Zn with weight percentages 28.44, 23.67 and 47.89 W%, respectively. The EDX spectrum of GO (Fig. 3C) exhibited signals for C and O with weight percentages 69.44 and 30.56 W%. EDX spectrum of the CMC/MOF-5/GO which presented the only existence of C, O, and Zn with weight percentages of 45.74, 33.63 and 20.63 W%, respectively, was indicated successful formation with high purity. The comparison of CMC/MOF-5/GO with pure CMC and GO exhibited the presence of Zn and increasing the intensity of C and O than MOF-5.

Fig. 3.

The EDX analysis for the pure CMC (a), GO (b), MOF-5 (c) and CMC/MOF-5/GO (d)

.

The EDX analysis for the pure CMC (a), GO (b), MOF-5 (c) and CMC/MOF-5/GO (d)

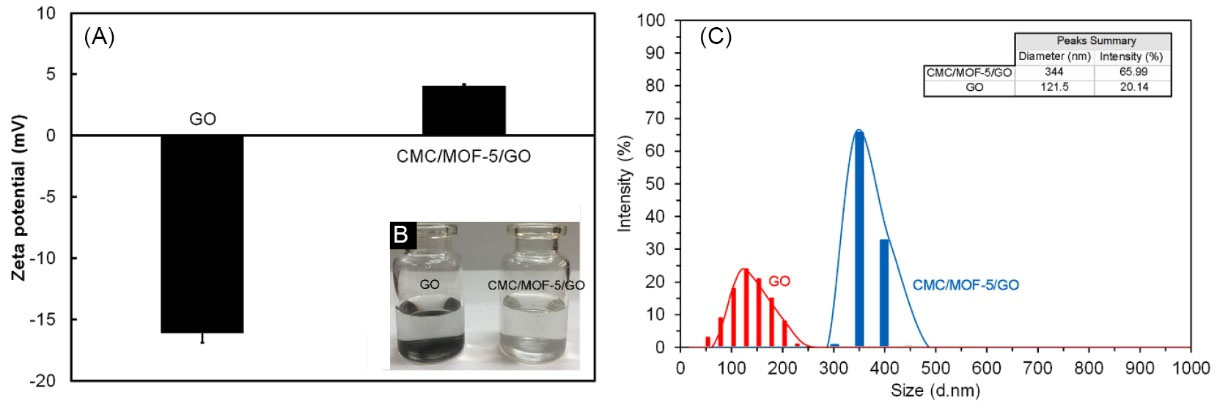

Zeta potential

The zeta potential results of GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO were provided to confirm the drug delivery ability of materials (Fig. 4A). The zeta potential of GO is about −16.1 mV because of –COO- groups on the GO. Due to the existence of Zn2+ in MOF-5, the zeta potential of CMC/MOF-5/GO is about +4 mV that is +20.1 mV much higher than GO.

Fig. 4.

The Zeta potential of the GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO (A). The stability comparison between GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO (B).

.

The Zeta potential of the GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO (A). The stability comparison between GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO (B).

Solubility analysis

Colloidal stability of the GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO was studied in 0.9 wt% NaCl solutions. However, in distilled water GO was well dispersed but in the physiological environment, it was easy to aggregate. As seen in Fig. 4B, in 0.9 wt% NaCl solutions, the GO (0.2 mg/mL) after a few hours was precipitated, while the CMC/MOF-5/GO (0.2 mg/mL) was still well dispersed for more than 20 days. Therefore, the solubility of CMC and MOF-5 modified GO was improved. This behavior of bio-nanocomposite effectively can be relative to the high solubility nature of CMC.

49

Size distribution analysis

The size of GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO were performed in aqueous solution by using DLS measurement. It was found that the average size of GO was 121.5 d.nm (Fig. 4C). However, after the modification of GO with CMC and MOF-5, an average size of CMC/MOF-5/GO 344 d.nm was obtained under the same instrumental conditions (Fig. 4C).

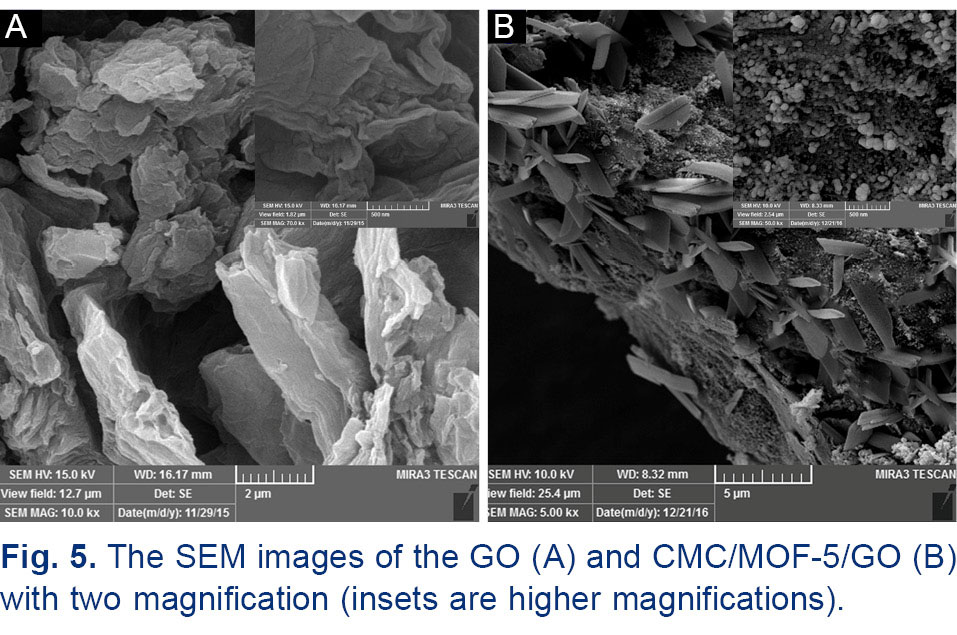

Morphological analysis

Fig. 5 shows the SEM images of the GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO. In Fig. 5a can be seen the agglomeration of stacked graphene sheets due to the strong specific interactions and dispersive forces between the surface groups on the graphene-like layers.

50

In contrast, the CMC/MOF-5/GO consists of a spongy structure with square and lamellar shapes on the graphene sheets, which was derived from the morphology of CMC and MOF-5 respectively (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

The SEM images of the GO (A) and CMC/MOF-5/GO (B) with two magnification (insets are higher magnifications).

.

The SEM images of the GO (A) and CMC/MOF-5/GO (B) with two magnification (insets are higher magnifications).

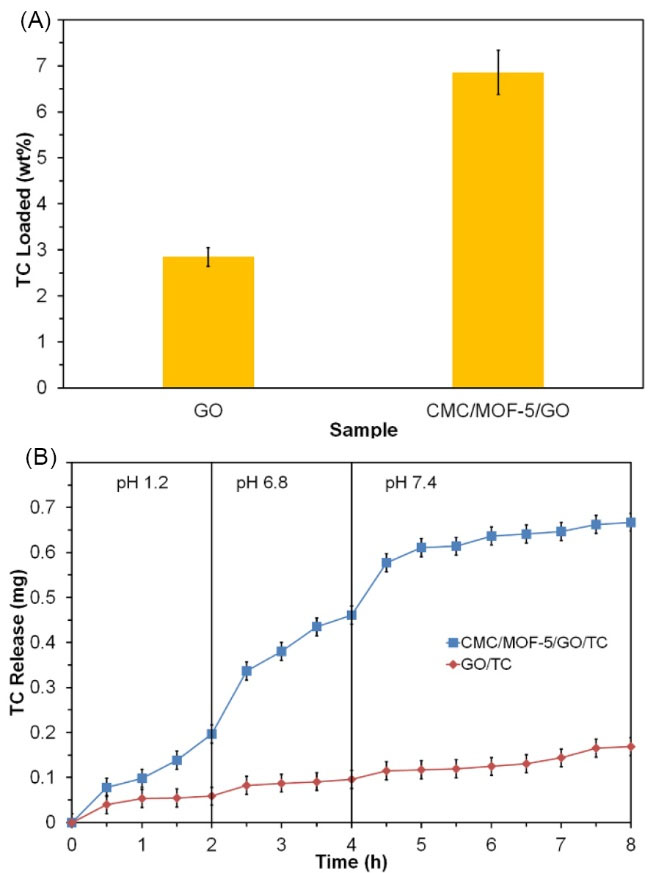

Drug loading and release

Pure TC drug was loaded in the GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO then the drug loading of carrier respectively was calculated 2.59 and 6.85 wt% using UV–Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 6). Since the loading of the drug was performed in the distilled water, the TC molecule is a zwitterion. In this condition, the surface of the CMC/MOF-5/GO in comparison with GO is partially positive charge that is seen in Zeta potential data.

51

Hence, it seems there is an attractive force between TC molecules and surface of the CMC/MOF-5/GO. This was supported by TC loading data which showed an increase in the TC loading capacity of the CMC/MOF-5/GO in comparison with GO. For elucidating the potential of the synthesized carrier as an oral DDS, drug release experiment was carried out in simulated conditions with in-vivo process. The Fig. 5b shows the release profiles of the TC-loaded GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO over 8 hours at 37oC. By comparing the charts, the amount of drug release is enhanced for CMC/MOF-5/GO than GO which might be due to the combination of CMC, MOF-5 and GO as the bio-nanocomposite structure. In the GO 0.12 mg, the drug was released at 8 hours while for CMC/MOF-5/GO the amount of drug release was 0.65 at 8 h. To reveal the drug release kinetics, the release data were fit using several models (Table 2), as described previously.

44

The release data were best fitted with Hixson–Crowell and, to some extent, with three seconds root of mass models (Table 1).

Fig. 6.

The TC release behavior of GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite in the conditions simulate to the gastrointestinal tract passage (pH and time).

.

The TC release behavior of GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite in the conditions simulate to the gastrointestinal tract passage (pH and time).

Table 2.

MIC values of TC, blank and TC-loaded GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO required for inhibition of S. aureus and E. coli

|

Tested sample

|

MIC (µg/mL)

|

|

S. aureus

|

E. coli

|

| TC |

62.5 |

250 |

| GO |

- |

- |

| CMC/MOF-5/GO |

1000 |

- |

| TC@GO |

500 |

- |

| TC@CMC/MOF-5/GO |

500 |

1000 |

Antibacterial activity tests

To assess the applicability of prepared bio-nanocomposite as an antibacterial agent, we tested them at different concentrations against S. aureus and E. coli. The microdilution method was employed to determine their MIC to evaluate their antibacterial activity. The evaluation included various concentrations of blank and TC-loaded GO and CMC/MOF-5/GO, in order to analyze and to compare the enhanced antibacterial behavior associated with modified bio-nanocomposite. Table 2 shows the MIC values of samples to inhibit both bacterial strains. The obtained data showed that the blank GO is not any antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli while the TC@GO show that antibacterial activity against S. aureus with the MIC of 500 µg/mL. Antibacterial activity against S. aureus with the MIC of 1000 µg/mL was shown for blank CMC/MOF-5/GO. However, for TC@CMC/MOF-5/GO, MIC of 500 and 1000 µg/mL are required to inhibit the growth of S. aureus and E. coli bacteria, respectively.

Discussion

Recently, much attention has been paid to developing new methods for designing new DDSs with the controlled drug release potentials.

52

In traditional drug delivery system, the drug dosage in the tissue increases rapidly and then drops.

53

Plasma level of each drug is described by overhead and under levels as toxic and ineffective, respectively.

54

An ideal drug delivery system should convey a suitable concentration of drug to targeting sites while other tissues will be kept safe.

3,55

Thus, one of the main challenges is finding a suitable delivery carrier to reach this goal. In this work, we have successfully composed GO with biopolymer CMC and MOF-5 in goals of enhanced solubility, antibacterial activity, delivery and controlled release of the drug into specific location. Drug loading and releasing experiments showed that the TC was efficiently loaded on and released from the CMC/MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite.

The FT-IR results could be good evidences for the interactions between the –COOH of GO, CMC, and BDC with Zn++ of CMC/MOF-5/GO. The XRD results prove that the GO component in the CMC/MOF-5/GO cannot induce a distortion in the crystalline structure of MOF-5 component.

43

The obvious change in size distribution indicated that the CMC and MOF-5 acted as a cross-linking agent to prepare the spongy structure of GO and the size diameter of CMC/MOF-5/GO particles was increased after the modification process. In order to clarify the effect of CMC and MOF-5 on the spongy structure of GO, the morphological analysis shows that some polymers may fill in the structure to support the framework, and some may react with the functional groups on the GO.

TC is an industrially available antibiotic used to treat a number of infections. This includes acne, cholera, brucellosis, plague, malaria and syphilis.

37

One of the major side effects which were observed after oral administration of TC is irritation of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). To decrease the high GIT side effects caused by severity of upon TC oral organization, the drug can be encapsulated into biocompatible support as enteric coated dosage forms. As well as, nanomaterial supports with high surface area such as GO could enhance the medicinal efficiency, and also the medical performance can be improved even more through modification of nanoparticle.

56

For this propose, during a specific period of time, carrier was suspended in the mediums with pH 1.2, pH 6.8 and pH 7.4 which respectively mimicked the pH of the simulated gastric fluid, the first zone of intestinal fluid and the second zone of intestinal fluid. Due to the high loading of the drug, the positive-charged and spongy structure of CMC/MOF-5/GO nanocarrier the TC release was enhanced and showed antibacterial activity to negatively charged E. coli bacteria compared with TC@GO. It is clear that there is a significant improvement in TC release and a strong antibacterial activity by modification with MOF-5 and CMC in comparison with bare GO.

Conclusion

In present work, we have successfully composed GO with biopolymer CMC and MOF-5 in aims of enhanced solubility, antibacterial activity, delivery and controlled release of drug into the specific location. Drug loading and releasing experiments showed that the TC was efficiently loaded on and released from the CMC/MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite. Antibacterial activity tests showed that the TC@CMC/MOF-5/GO has an antibacterial activity to negatively charge E. coli bacteria compared with TC@GO. These properties are related to the water-soluble and positively charge features of CMC/MOF-5/GO which was created by modification of GO with CMC and MOF-5. According to the results, the TC-loaded CMC/MOF-5/GO can be considered as potential candidates for targeted delivery and controlled release of oral delivery.

Acknowledgments

Authors gratefully acknowledge the University of Tabriz and Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for the supporting of this work.

Funding sources

This work is a part of Z. Karimzadeh and S. Javanbakht thesis which funded with University of Tabriz.

Ethical statement

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Authors contribution

ZK, SJ and HN conceived and planned the project, the main conceptual ideas and design of the experiments. ZK and SJ implemented the experiments. ZK, SJ and HN contributed to data analysis and interpretation of the results. SJ was in charge of writing the manuscript. HN contributed to writing and also reviewing final version of the manuscript. All authors provided helpful feedback.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

simple

-

√ Carboxymethylcellulose/MOF-5/GO bio-nanocomposite

(CMC/MOF-5/GO) successfully synthesized using the

solvothermal technique.

-

√ Tetracycline (TC) was encapsulated in the GO and CMC/

MOF-5/GO.

-

√ The drug release profiles showed that the TC-loaded CMC/

MOF-5/GO has an effective protection functionality against

stomach pH.

What is new here?

simple

-

√ With controlling the TC release in the gastrointestinal

tract conditions, the long-time stability of drug dosing was

enhanced.

-

√ The collected data showed that the TC-loaded CMC/MOF-

5/GO has the antibacterial activity to negatively charge E. coli

bacteria in contrast to TC-loaded GO.

References

- Pan Q, Lv Y, Williams GR, Tao L, Yang H, Li H. Lactobionic acid and carboxymethyl chitosan functionalized graphene oxide nanocomposites as targeted anticancer drug delivery systems. Carbohydr Polym 2016; 151:812-20. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.06.024 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Panyam J, Labhasetwar V. Biodegradable nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to cells and tissue. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2003; 55:329-47. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00228-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Langer R. Drug delivery and targeting. Nature 1998; 392:5-10. [ Google Scholar]

- Namazi H, Jafarirad S. Application of hybrid organic/inorganic dendritic ABA type triblock copolymers as new nanocarriers in drug delivery systems. Int J Polym Mater 2011; 60:603-19. doi: 10.1080/00914037.2010.531824 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Namazi H, Babazadeh M, Sarabi A, Entezami A. Synthesis and hydrolysis of acrylic type polymers containing nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Journal of Polymer Materials 2001; 18:301-311. [ Google Scholar]

- Namazi H, Rakhshaei R, Hamishehkar H, Kafil HS. Antibiotic loaded arboxymethylcellulose/MCM-41 nanocomposite hydrogel films as potential wound dressing. Int J Biol Macromol 2016; 85:327-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.12.076 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Brooks AE, Brooks BD, Davidoff SN, Hogrebe PC, Fisher MA, Grainger DW. Polymer-controlled release of tobramycin from bone graft void filler. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2013; 3:518-30. doi: 10.1007/s13346-013-0155-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Namazi H. Polymers in our daily life. BioImpacts 2017; 7:73. doi: 10.15171/bi.2017.09 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Son JS, Appleford M, Ong JL, Wenke JC, Kim JM, Choi SH. Porous hydroxyapatite scaffold with three-dimensional localized drug delivery system using biodegradable microspheres. J Control Release 2011; 153:133-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.03.010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Namazi H, Adeli M. Dendrimers of citric acid and poly (ethylene glycol) as the new drug-delivery agents. Biomaterials 2005; 26:1175-83. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abraham SA, Waterhouse DN, Mayer LD, Cullis PR, Madden TD, Bally MB. The liposomal formulation of doxorubicin. Methods Enzymol 2005; 391:71-97. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)91004-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shariatinia Z, Zahraee Z. Controlled release of metformin from chitosan–based nanocomposite films containing mesoporous MCM-41 nanoparticles as novel drug delivery systems. J Colloid Interface Sci 2017; 501:60-76. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.04.036 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Davis ME, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008; 7:771-82. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Huang Z-H, Liu G, Kang F. Glucose-promoted Zn-based metal– organic framework/graphene oxide composites for hydrogen sulfide removal. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2012; 4:4942-7. doi: 10.1021/am3013104 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- James SL. Metal-organic frameworks. Chem Soc Rev 2003; 32:276-88. doi: 10.1039/B200393G [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Namvari M, Namazi H. Synthesis of magnetic citric‐acid‐functionalized graphene oxide and its application in the removal of methylene blue from contaminated water. Polym Int 2014; 63:1881-8. doi: 10.1002/pi.4769 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H, Cordova KE, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 2013; 341:1230444. doi: 10.1126/science.1230444 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Horcajada P, Gref R, Baati T, Allan PK, Maurin G, Couvreur P. Metal–organic frameworks in biomedicine. Chem Rev 2011; 112:1232-68. doi: 10.1021/cr200256v [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Geim AK, Novoselov KS. The rise of graphene. Nat Mater 2007; 6:183-91. [ Google Scholar]

- Patel DK, Senapati S, Mourya P, Singh MM, Aswal VK, Ray B. Functionalized graphene tagged polyurethanes for corrosion inhibitor and sustained drug delivery. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2017; 3:3351-63. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00342 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Namvari M, Namazi H. Clicking graphene oxide and Fe 3 O 4 nanoparticles together: an efficient adsorbent to remove dyes from aqueous solutions. Int J Environ Sci Technol 2014; 11:1527-36. doi: 10.1007/s13762-014-0595-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Petit C, Bandosz TJ. MOF–graphite oxide composites: combining the uniqueness of graphene layers and metal–organic frameworks. Adv Mater 2009; 21:4753-7. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901581 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li L, Shi Z, Zhu H, Hong W, Xie F, Sun K. Adsorption of azo dyes from aqueous solution by the hybrid MOFs/GO. Wat Sci Tech 2016; 73:1728-37. doi: 10.2166/wst.2016.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jahan M, Bao Q, Yang J-X, Loh KP. Structure-directing role of graphene in the synthesis of metal− organic framework nanowire. JACS 2010; 132:14487-95. doi: 10.1021/ja105089w [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Petit C, Levasseur B, Mendoza B, Bandosz TJ. Reactive adsorption of acidic gases on MOF/graphite oxide composites. Micropor Mesopor Mat 2012; 154:107-12. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.09.012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Xu X, Liang X, Lei C, Gao L, Hao R. Fabrication of Ce doped UiO-66/graphene nanocomposites with enhanced visible light driven photoactivity for reduction of nitroaromatic compounds. Appl Surf Sci 2017; 420:276-85. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.05.158 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Simões S, Moreira JN, Fonseca C, Düzgüneş N, de Lima MCP. On the formulation of pH-sensitive liposomes with long circulation times. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2004; 56:947-65. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.038 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Barkhordari S, Yadollahi M. Carboxymethyl cellulose capsulated layered double hydroxides/drug nanohybrids for Cephalexin oral delivery. Appl Clay Sci 2016; 121:77-85. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2015.12.026 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Barkhordari S, Yadollahi M, Namazi H. pH sensitive nanocomposite hydrogel beads based on carboxymethyl cellulose/layered double hydroxide as drug delivery systems. J Polym Res 2014; 21:454. doi: 10.1007/s10965-014-0454-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yadollahi M, Namazi H, Aghazadeh M. Antibacterial carboxymethyl cellulose/Ag nanocomposite hydrogels cross-linked with layered double hydroxides. Int J Biol Macromol 2015; 79:269-77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.05.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yadollahi M, Farhoudian S, Namazi H. One-pot synthesis of antibacterial chitosan/silver bio-nanocomposite hydrogel beads as drug delivery systems. Int J Biol Macromol 2015; 79:37-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.04.032 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yadollahi M, Gholamali I, Namazi H, Aghazadeh M. Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial carboxymethylcellulose/CuO bio-nanocomposite hydrogels. Int J Biol Macromol 2015; 73:109-14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.10.063 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yadollahi M, Namazi H. Synthesis and characterization of carboxymethyl cellulose/layered double hydroxide nanocomposites. J Nanopart Res 2013; 15:1563. doi: 10.1007/s11051-013-1563-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yadollahi M, Gholamali I, Namazi H, Aghazadeh M. Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial carboxymethyl cellulose/ ZnO nanocomposite hydrogels. Int J Biol Macromol 2015; 74:136-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.11.032 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rasoulzadeh M, Namazi H. Carboxymethyl cellulose/graphene oxide bio-nanocomposite hydrogel beads as anticancer drug carrier agent. Carbohydr Polym 2017; 168:320-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.11.032 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Araque E, Villalonga R, Gamella M, Martínez‐Ruiz P, Sánchez A, García‐Baonza V. Water‐Soluble Reduced Graphene Oxide– Carboxymethylcellulose Hybrid Nanomaterial for Electrochemical Biosensor Design. ChemPlusChem 2014; 79:1334-41. doi: 10.1002/cplu.201402017 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chopra I, Roberts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2001; 65:232-60. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht S, Namazi H. Doxorubicin loaded carboxymethyl cellulose/graphene quantum dot nanocomposite hydrogel films as a potential anticancer drug delivery system. Mater Sci Eng C 2018; 87:50-9. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.02.010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht S, Nazari N, Rakhshaei R, Namazi H. Cu-crosslinked carboxymethylcellulose/naproxen/graphene quantum dot nanocomposite hydrogel beads for naproxen oral delivery. Carbohydr Polym 2018; 195:453-9. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.103 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Namvari M, Namazi H. Clicking graphene oxide and Fe3O4 nanoparticles together: an efficient adsorbent to remove dyes from aqueous solutions. Int J Environ Sci Technol 2014; 11:1527-36. doi: 10.1007/s13762-014-0595-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kabiri R, Namazi H. Nanocrystalline cellulose acetate (NCCA)/ graphene oxide (GO) nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical properties and barrier against water vapor. Cellulose 2014; 21:3527-39. doi: 10.1007/s10570-014-0366-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tang Z, Shen S, Zhuang J, Wang X. Noble‐metal‐promoted three‐dimensional macroassembly of single‐layered graphene oxide. Angew Chem 2010; 122:4707-11. doi: 10.1002/ange.201000270 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hafizovic J, Bjørgen M, Olsbye U, Dietzel PD, Bordiga S, Prestipino C. The inconsistency in adsorption properties and powder XRD data of MOF-5 is rationalized by framework interpenetration and the presence of organic and inorganic species in the nanocavities. JACS 2007; 129:3612-20. doi: 10.1021/ja0675447 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Matthaiou E-I, Barar J, Sandaltzopoulos R, Li C, Coukos G, Omidi Y. Shikonin-loaded antibody-armed nanoparticles for targeted therapy of ovarian cancer. Int J Nanomedicine 2014; 9:1855. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S51880 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Barzegar-Jalali M, Adibkia K, Valizadeh H, Shadbad MRS, Nokhodchi A, Omidi Y. Kinetic analysis of drug release from nanoparticles. J Pharm Pharm Sci 2008; 11:167-77. [ Google Scholar]

-

Waitz JA. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1990.

- Andrews JM. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J Antimicrob Chemoth 2001; 48:5-16. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_1.5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cao N, Zhang Y. Study of reduced graphene oxide preparation by Hummers’ method and related characterization. J Nanomater 2015; 2015:168125. doi: 10.1155/2015/168125 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang LM. New Water‐Soluble Cellulosic Polymers: A Review. Macromol Mater Eng 2001; 286:267-75. doi: 10.1002/1439-2054(20010501)286:5<267::AID-MAME267>3.0.CO;2-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Petit C, Bandosz TJ. MOF–graphite oxide nanocomposites: surface characterization and evaluation as adsorbents of ammonia. J Mater Chem 2009; 19:6521-8. doi: 10.1039/B908862H [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Singh B, Chauhan G, Sharma D, Chauhan N. The release dynamics of salicylic acid and tetracycline hydrochloride from the psyllium and polyacrylamide based hydrogels (II). Carbohydr Polym 2007; 67:559-65. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.06.030 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Wang J, Wang Y, Zhao L, Li Y, Liu C. Formation of graphene oxide-hybridized nanogels for combinative anticancer therapy. Nanomed Nanotechnol 2018; 14:2387-95. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.05.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Zhang Z, Yu J, Chen H, Li X. Self-assembly of a ibuprofen-peptide conjugate to suppress ocular inflammation. Nanomed Nanotechnol 2018; 14:185-93. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.09.010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bao H, Pan Y, Ping Y, Sahoo NG, Wu T, Li L. Chitosan‐functionalized graphene oxide as a nanocarrier for drug and gene delivery. Small 2011; 7:1569-78. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100191 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rahmanian N, Eskandani M, Barar J, Omidi Y. Recent trends in targeted therapy of cancer using graphene oxide-modified multifunctional nanomedicines. J Drug Target 2017; 25:202-15. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2016.1238475 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ting JM, Navale TS, Jones SD, Bates FS, Reineke TM. Deconstructing HPMCAS: excipient design to tailor polymer– drug interactions for oral drug delivery. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2015; 1:978-90. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00234 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]